America’s unemployment rate is hovering at historic lows. The percentage of prime-age Americans in the labor force is higher than it’s been since the 2008 financial crisis. Thanks to an abundance of employment opportunities, lower-income workers have recovered roughly 25 percent of the increase in wage inequality that accrued between Ronald Reagan’s election and Joe Biden’s. Inflation is falling. A gallon of gasoline costs roughly 30 percent less than it did one year ago.

One popular gauge of the economy’s strength is the “misery index,” which simply adds together the unemployment and inflation rates. That index is lower now than it’s been during 83 percent of all months since 1978.

Meanwhile, Joe Biden’s plans for increasing manufacturing employment and investment in the United States are going swimmingly. Manufacturing-plant construction has doubled since the end of 2021, and real spending on the forms of manufacturing most incentivized by the president’s CHIPS law and Inflation Reduction Act — computer, electronics, and electrical production — has nearly quadrupled over the past year. To no small extent, Biden has delivered what Trump only promised: Foreign leaders are fuming as the president’s subsidies persuade overseas firms to shift production to the United States.

At the same time, the president’s policies have lowered prescription-drug costs for seniors and health-insurance premiums for those who purchase coverage over the individual market.

And yet, Biden is one of the most unpopular presidents in modern American history, with 54.4 percent of voters disapproving of his job performance in FiveThirtyEight’s polling average. And the public’s views of his economic management are especially dour: A recent AP-NORC Center poll finds only one-third of voters approving of Biden’s handling of the economy.

Many Democrats have found this state of affairs perplexing. Last week, I argued that the public’s hostility to Biden in general, and his economic stewardship in particular, was misguided but comprehensible. After all, real wages and real personal disposable income have both declined during the president’s time in office. The pandemic reduced the global economy’s productive capacity by disrupting supply chains, abruptly shifting consumer spending patterns, and severing ties between workers and employers. We could have paid for this damage through a sustained period of elevated unemployment. Instead we paid for it with a decline in real wages. This was the better option on the merits. So even though the Biden economy looks very good, it wasn’t hard to understand why many voters would be displeased by the fact that they cannot afford as high of a living standard now as they did before the pandemic.

Since writing that column, I’ve learned that one of my key assumptions was faulty. Although the average real hourly wage for production and nonsupervisory workers has declined since Biden took office, that drop likely derives in part, if not in full, from changes in the composition of the labor force.

During the COVID recession, layoffs were heavily concentrated on the lowest rungs of the income ladder. Low-wage workers in the service industry lost their jobs en masse while white-collar workers largely (though, of course, not universally) retained their posts. Subtract a wide swath of low-income workers from the working population, and the average real wage among that population will go up: Between February 2020 and April 2020, the average real hourly wage in the U.S. jumped by nearly 6 percentage points. But this was not because U.S. employers decided that the best way to respond to a brutal recession was to hand out big raises. Very few workers actually saw their pay increase during that period.

Since Biden took office in January 2021, the economy has been steadily replacing the jobs it lost during the pandemic. This recovery has necessarily brought more lower-wage workers back into the labor force. It is hard to say exactly what percentage of the apparent decline in real wages this composition effect accounts for. But if we use the month before the pandemic started as a baseline — since, in February 2020, the unemployment rate (and thus composition of the labor force) was similar to today — then the real wage picture looks very different: Even after accounting for inflation, the real hourly wage in the U.S. is now nearly 2 percent higher than it was before the pandemic.

A less than 2 percent advance in real wages over more than two years isn’t fabulous. But it nevertheless means that, using one plausible measure, American workers actually have higher living standards now than they did before the pandemic, when their assessments of the economy were historically positive. Shortly before COVID, a CNN poll found voters viewing the economy more favorably than they had in nearly 20 years. Today, Americans are earning higher real wages than they did then. And consumer sentiment is, nevertheless, lower than it has been during 92 percent of the months since 1978.

So, the unpopularity of both Biden and his economy are stranger than I’d previously allowed.

If “real wages are falling” isn’t a persuasive explanation for Biden’s unpopularity, a “rising wave of unhappiness” isn’t either. Deepak Bhargava, Shahrzad Shams, and Harry Hanbury floated that hypothesis in their recent essay on Biden’s mysterious unpopularity. Those authors argued that, although Biden has delivered material improvements to voters, his policies have failed to redress their widespread sense of despair. Americans might have grown richer in recent years, but they’ve also grown more socially isolated, as civic institutions like churches and unions have declined. Meanwhile, social media has been eroding our collective self-esteem, and the climate crisis has been raising our anxiety. A crisis of unhappiness has resulted. As the authors write:

Since 1990, the number of Americans reporting they feel “not too happy” has been trending upward, particularly among those without a college education. The onset of the pandemic only exacerbated the growing national unhappiness: By 2021, just 19 percent of Americans reported that they felt “very happy”—the lowest level on record since the General Social Survey began asking the question in 1972. The intensifying unhappiness is also reflected in data showing that more and more Americans are overdosing on drugs and that the suicide rate has increased by about 30 percent over the last couple of decades. Our culture and politics are increasingly driven by this rising wave of unhappiness.

Happily, this is a rather misleading framing of the available data on Americans’ subjective well-being. It is true that the percentage of Americans who say they are “very happy” has fallen precipitously since the pandemic. Nevertheless, in 2022, 80 percent of Americans characterized their general emotional state as either “very happy” or “pretty happy,” in the General Social Survey.

That finding is consistent with Gallup’s polling on Americans’ “life satisfaction.” In February 2023, 83 percent of that poll’s respondents said that they were either “very” or “somewhat” satisfied with “the way things are going in your personal life.” For a supermajority of Americans, this contentment carried over into evaluations of their economic lives. Seventy-six percent said that they were satisfied with “their standard of living,” and 71 percent said the same about their household income. On non-material issues, contentment was even more predominant, with 90 percent of respondents expressing satisfaction with their family lives.

There are plenty of reasons to discount these findings. It’s conceivable that this sort of polling is systematically marred by social desirability bias, as respondents feel self-conscious about confessing their unhappiness or dissatisfaction. Nevertheless, to the extent that we can measure Americans’ degree of subjective well-being, they appear to be overwhelmingly satisfied with both the economic and non-material aspects of their lives.

To my mind, the drug overdose crisis does not constitute a refutation of this picture. As I’ve written elsewhere, I think there’s a lamentable tendency for commentators across the ideological spectrum to marshal the opioid crisis as a demonstration of whatever diffuse social trend they wish to condemn. Certainly, that crisis has some socioeconomic and social determinants. But I think there’s good reason to think that it is primarily the product of highly contingent policy decisions and technological developments.

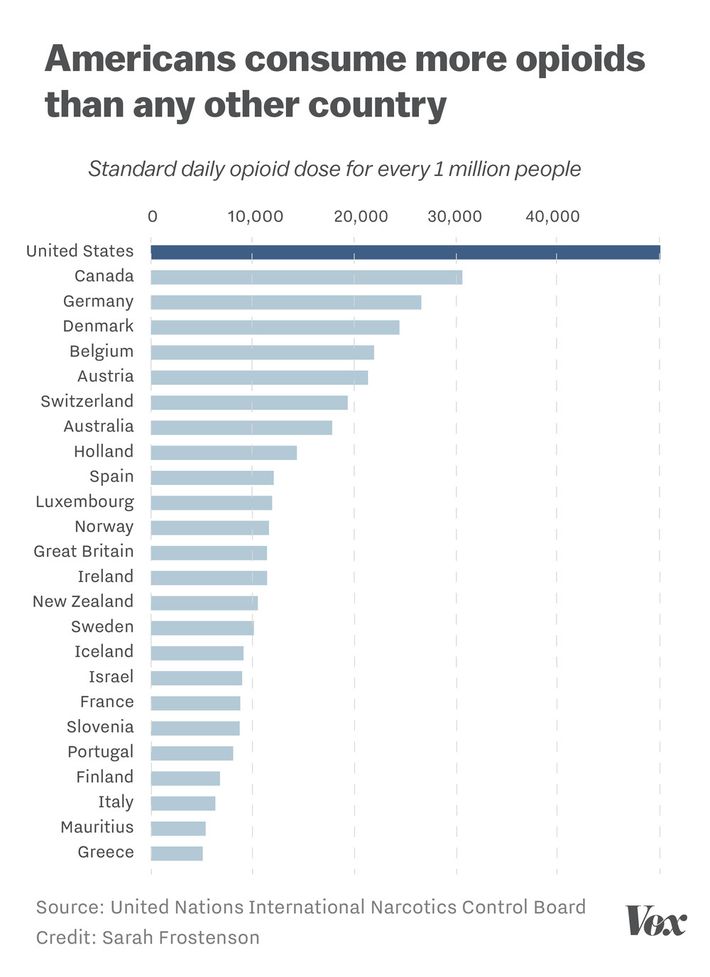

For one thing, the county-level correlation between economic hardship and “deaths of despair” is extremely weak. For another, many of the social trends that commentators blame for the opioid crisis — deindustrialization, stagnant or falling working-class wages, offshoring, and atomization — are present across a wide range of advanced industrial nations. Working-class people in many European countries have suffered much larger declines in living standards than their peers in the U.S. Yet America’s rate of drug overdose deaths is exceptionally high.

One simple explanation for this discrepancy is that the United States, unlike virtually all of its peers, allowed Purdue Pharma to mass market Oxycontin as a safe treatment for chronic pain for decades. U.S. doctors therefore came to prescribe opioids at a radically higher rate than those overseas. This seeded widespread consumer appetite for such drugs. When the federal government finally clamped down on prescription pills, fentanyl rushed in to fill the void, drastically increasing the lethality of street drugs in the process.

In any event, while the opioid epidemic itself has surely brought despair into many Americans’ lives, it does not seem like a better indicator of national happiness than survey data.

So, if most Americans have objectively seen an increase in living standards since the pandemic and subjectively feel satisfied with both their economic and nonmaterial circumstances, why are they so dissatisfied with their president and his economic record?

One possibility is that, after enjoying largely stable prices for decades, Americans simply have little tolerance for inflation. Sure, their wages may have grown faster than prices since February 2020. But voters might be inclined to attribute their income gains to their own efforts, while blaming rising prices on the government’s mismanagement. They still have not adjusted psychologically to the jump in their grocery bills, and are irked each time they see the receipt and remember what things used to cost when Donald Trump was still president.

Another, related possibility, is that the American middle class resents many aspects of a tight labor market. For households earning the median wage or above, falling income inequality might be experienced as a loss in relative social status. More concretely, as wages have risen at the bottom of the labor market and competition for low-wage workers among employers has intensified, it may be harder to get “good help” these days, whether in the form of affordable housecleaners, child-care workers, or timely restaurant service.

That said, neither of these explanations do a great job of accounting for the fact that a supermajority of Americans express satisfaction with their personal economic circumstances. By contrast, a disconnect between perceptions of one’s own material wellbeing, and perceptions of the economy writ large, could be explained by media dynamics.

Certainly, right-wing media in the United States has vast reach and influence. The mainstream media, meanwhile, has a well-documented negativity bias, which has generated years of stories about a hypothetical recession, whose start date is forever being postponed.

Another theory is that voters are simply put off by Biden’s extraordinarily advanced age and are inclined to believe that an 80-year-old president is probably mismanaging the economy in some way.

This is far from an exhaustive list of potential explanations. I’m personally inclined to think that the answer is some combination of the public’s (perhaps, irrationally intense) antipathy for inflation and media dynamics. Regardless, widespread disapproval of both Biden and the economy is much weirder than a cursory look at real-wage data would lead one to believe.