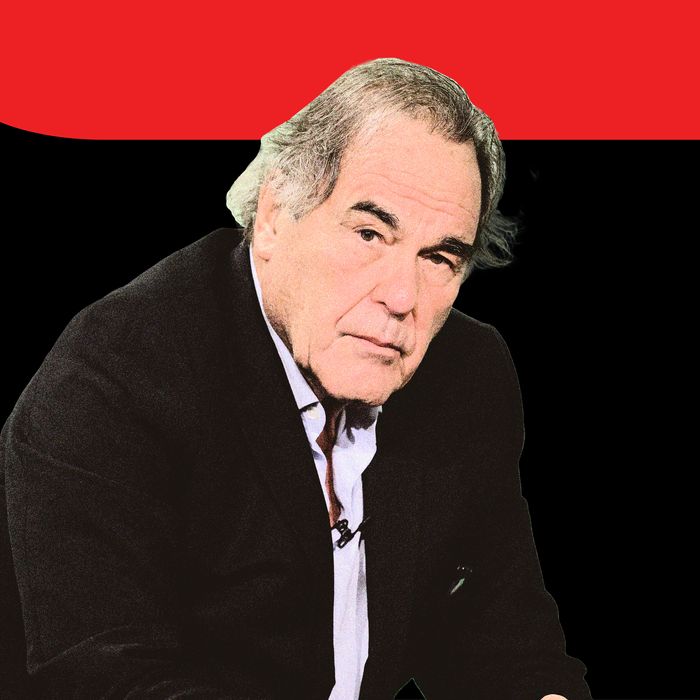

Longtime filmmaker Oliver Stone has never been shy when it comes to contentious topics or going after accepted thinking. But his new documentary, Nuclear Now — which makes the case for nuclear energy as a silver (not magic) bullet against climate change and the literal end of the world — has a more hopeful tone than most of his earlier work. In the latest episode of On With Kara Swisher, Kara talks to Stone about the film, that shift, and what turns an infamous counterculture warrior into an advocate for nuclear-power plants. In the below excerpt, Swisher and Stone discuss the pros and cons of atomic energy, the decades-old efforts to demonize it, Hollywood’s role in that, and why, in Stone’s mind, more nuclear accidents might have actually done some good.

On With Kara Swisher

Subscribe on:

Kara Swisher: You’ve made over 30 films. You’ve told stories about Vietnam War, greed on Wall Street, figures like JFK, Nixon, Bush, Edward Snowden, Vladimir Putin, and now nuclear energy and climate change. What’s the through line of your career, at what you’re trying to build here with this body of work across complicated, often controversial topics?

Oliver Stone: Well, one doesn’t think about it in terms of — when you’re a young person, you don’t say I’m gonna be this at the end of my life. You just do it as you go, and the issues that concern you often concern the rest of the world. I mean, I have been very conscious of the news, I was raised that way in New York City by my father who was conscious of the news, and I’ve always been interested in who’s president and economic policy. My father was an economist — and trying to follow the trends. Nuclear energy, I mean, the concept of clean energy has been haunting for the last few years. Everyone’s talking about it since they’ve acknowledged climate change, since let’s say the 2000 period. And certainly, Al Gore’s film brought attention to it in 2006. So it’s scary. It’s — even if you don’t accept climate change and some people don’t — what, how, what is the best way to utilize energy in our country? And that could be conservation conscious? And in that regard, when you do the research and you go around and you talk to the scientists, people who know, who don’t just have opinions but who know, it comes out that nuclear energy is a must — is a must.

Kara Swisher: But what made you do that? You said most of your films unpack a lie. You say undiscovered lies that people won’t admit, I think in an interview. Explain the lie that got you motivated to do an entire documentary, a two-hour, almost two-hour documentary.

Oliver Stone: Well, I didn’t see, I didn’t see it as a lie when I started. It was simply to deal with this issue of where are we going? I mean, everyone was talking about taking pro-nuclear, anti-nuclear positions. It’s tedious to listen to these arguments because it’s a what if, what if, what if, kind of question mark. We want to move beyond that and try to solve the problem. So when I read this book called A Bright Future written by Josh Goldstein, who was a professor of international relations, and a nuclear engineer, scientist from Sweden called Stefan Swiss. They laid out in a very simple book, it was very clear — it’s very dry and hard to read — but it’s clear that we’re going to need a lot of nuclear energy in the next 30 years to meet the standards of what the IPCC calls — 2050 is going to be kind of a — breakpoint, when the earth is gonna no longer be able to recover from warming, and it will just keep warming itself.

Let’s say that’s true, but even if it were not true, I would still be saying, and these books would still be saying we need nuclear energy, and we had it, it worked.

Kara Swisher: Sure. I guess what I want to get to is like, why this? There’s crisis all over the world, including misinformation, political partisanship. What prompted you to come to this. You read a book that you liked, right? Uh, there’s lots of books and lots of —

Oliver Stone: Because I’m scared. I’m scared for the world. I have children, hopefully I’ll have grandchildren. What’s my daughter and son gonna face? It’s the prospect of the earth getting worse, is what scares me. The earth should be getting better because we know, we know more and more and more and we have more tools that help us and we’re not. It’s not getting better. The carbon dioxide poisoning in the air, along with the methane gas poisoning in the air, is growing.

Kara Swisher: So this compelled you to make an argument that the answer is, the solution is nuclear energy. So I want you to explain why you think nuclear is the answer and compare it to solar, wind and other forms of renewable energy that we’ve been sold on. Cause it’s — you can get more out of it. More bang for your buck, so to speak.

Oliver Stone: Yeah. Well, because nuclear operates 24-7, I mean, it’s basically a capacity of about 90 percent plus. It’s always going night and day. Once it’s built, it’s expensive, [but] once it’s built, the maintenance is very smooth and and it runs and it runs and we take it for granted, and we took it for granted in our country. And we never really kind of realized it. We looked to one accident, which was Chernobyl, which terrified the world —

Kara Swisher: And Three Mile Island.

Oliver Stone: I understand why, but that one accident became the basis for closing up nuclear plants, not only in Germany, but even in the United States. Closing them early.

Kara Swisher: And the others, the others, solar, wind are not, renewables are not good enough. They’re too small.

Oliver Stone: Too small on the scale that we need. We need continent size. Plus it takes up a lot of land. you know, in Germany for example, they put up solar panels in a huge solar park, 400, almost 500,000 panels, reflecting the sun. Those panels produced about one tenth of what nuclear produced on five times the size of the land. And the same is kind of true about turbines too, because they take a lot of space.

You know, if we can do it, we should do everything we can. Everything we can.

Kara Swisher: I wanna talk about why we’re not using it. You make a case at the beginning of the documentary about this quite clear, and it’s largely around safety and fear of accidents, essentially. You yourself said you used to be afraid of nuclear energy. What convinced you that it was safe? Because a lot of our fears come from the nuclear bomb, right? So we equate the two.

Oliver Stone: Nuclear bomb and nuclear energy have been conflated into one monster. And the truth is the nuclear bomb is enriched with plutonium, and it makes it highly radioactive and it’s dangerous. It happened at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which we set off, and people died of radioactive poisoning. But nuclear energy was made in a much lower-level way. The enrichment process is monitored highly by the IAEA, International Atomic Energy Commission. These plants are very, very safe. They’re built along these lines, very strictly in the United States, too strictly. You might argue that there should have been more accidents, because as in any new industry — chemicals, gas, oil, pipelines — there’s a process of learning. I think they did a pretty damn good job. They had one accident in the United States. It was at Three Mile Island and nobody died. The containment structure worked at Three Mile Island, and yet the panic was —

Kara Swisher: So you’re saying it became demonized in this, you know, a nuclear bomb —

Oliver Stone: It was demonized, yeah, by that film by Jane Fonda. That was — and I admire Jane very much for her Vietnam stand, as you know — but it made hysterical. The concept grew, this thing blows up, it’s gonna be a —

Kara Swisher: I’m curious, have you heard from Jane Fonda on this?

Oliver Stone: No, I haven’t, but I wish she would to look at it. I probably — it’s very hard to go back on your thinking and change your mind, but you have to listen to facts.

Kara Swisher: So what changed your mind? You said you were in that camp you were in, in that

Oliver Stone: Yeah, but I wasn’t — I assumed that people knew what they were talking about, but the truth is that the nuclear industry never really had a lobby. They never had, you know, what Wyoming has with coal, or Texas has with oil. They didn’t have a constituency. And no scientists, there was no Einstein around or guess, or Marie Curie, who found radium, to explain it to the people so that they would understand it. And the media got involved, and let’s be honest — they love hysteria. They love sensationalism. When you can talk about an explosion in your backyard the size of a nuclear bomb, it’s gonna make the news. But that’s not the case.

Kara Swisher: All right. We’ll get to the media in a second, but let’s play a clip from the documentary to start. This is President Eisenhower sharing his vision for nuclear energy in a speech to the UN in 1953, followed by your voiceover. Let’s play that.

President Eisenhower: This greatest of destructive forces can be developed into a great boon for the benefit of all mankind. Experts would be mobilized to apply atomic energy to the needs of agriculture, medicine, and other peaceful activity. A special purpose would be to provide abundant electrical energy in the power starved areas of the world. The United States pledges before you to devote its entire heart and mind to find the way by which the miraculous inventiveness of man shall not be dedicated to his death, but consecrated to his life.

Stone (narration): The entire assembly of delegates from around the world, including the Soviet Union, responded with warm and sustained applause.

Kara Swisher: Okay, we’re not exactly living in this nuclear-powered utopia he promised. You argue a few things are to blame. Let’s do a lightning round of some of these things you say have gotten in the way. Let’s start with Big Oil and economic interests here. How did they change things?

Oliver Stone: Well, as we explained in the film, they knew that this was a threat to their livelihood and their profits. And the Rockefeller Foundation put out a study in 1956, which put its thumb on the scale, and their scientists that were paid for by —

Kara Swisher: This is the oil family.

Oliver Stone: — came out with this conclusion that any amount of radiation is harmful to the human body. This is a study that went right to the New York Times front page. The publisher of the Times was, incidentally, on the board of the Rockefeller Foundation. What happened is that that report is fraudulent and it has been denied by science. It’s been discredited. Low level radiation exists all over the world. It’s with us, its cosmic rays bombard the earth, the sun. We are we’re exposed to radiation, low-level radiation all day long. And people at high levels of altitude or in airliners are more exposed to it and so forth and so on.But when you have that kind of news and then it sticks around. So that perception was there from almost the beginning, from 1956.

Kara Swisher: So they created this lie. They created a lie, bad PR, they put bad PR against it by saying you could die.

Oliver Stone: Well there’s low level radiation and there’s high level radiation. High level radiation is dangerous. The bomb stuff is high level radiation because it’s enriched. The nuclear plant radiation is low level.

Kara Swisher: So Big Oil tried to scare people into thinking you could be mutated.

Oliver Stone: Well they did. And also they went on, in time and now they have declared themselves the perfect partner for renewables. You see why? Because we know that renewables, sun and wind do not work all the time. So what’s the backup? It’s immediately: gas.

Kara Swisher: Coal and gas. Okay. So you talk about the co-opting of environmental groups about a Big Oil’s anti-nuclear agenda, that they shifted. Initially the Sierra Club was pro-nuclear energy and then became anti, and including the Friends of the Earth who was funded by Big Oil. Talk about that.

Oliver Stone: Yeah. It’s very hard to follow the money because it’s always anonymously given, but definitely, Rod Adams in the film tells the story of the Arco investment in Friends of the Earth. Friends of the Earth was one of the first anti-nuclear environmental groups, around 1970. but the chief of Arco Oil & Gas wrote the first check for $200,000 to Friends of the Earth. They got into the business of protesting nuclear energy. Not all the environmental groups did at first, but certainly a lot of them did. Greenpeace followed in 1970. Greenpeace –

Kara Swisher: And so, because why? Because oil was controlling them? I think that’s hard to believe, but that they may have gotten their initial funding from that, but what happened to these groups?

Oliver Stone: Well, who knows what funding continued. We don’t know where the funds come from,, but the point is it, even if it’s not a conspiracy, it’s business as usual — which is the oil companies don’t want to have competition from nuclear.

Kara Swisher: From nuclear. Okay. So we’ve talked about the conflation of nuclear energy and nuclear war. And you point a finger at Hollywood for fear-mongering. How did the films and TV stoke the fear. Obviously, you’ve got Godzilla, that came out after the bomb, you know, Duck and Cover, and then The China Syndrome — all kinds of movies. There’s one movie after the next.

Oliver Stone: Yeah. You don’t forget Silkwood, which is wonderfully filmed with Meryl Streep.. These people are — the film business has been horrible to the nuclear industry. We had all the horror films in the fifties when I was growing up. You know, everything was radioactive. There was always the reason for two heads monsters that existed, fish that came out the sea. Everything that was horrible came from radiation. On top of that, you had this HBO series about Chernobyl, which was extremely successful around the world.

Kara Swisher: So why is Hollywood doing this? The fear — what you call fearmongering.

Oliver Stone: Because they don’t know. Because they don’t know. And it makes, you know, it makes for easy, it’s an easy, what do they call it? It’s a low hanging fruit.

Kara Swisher: You imagine there being a movie? Nuclear Energy Is Great.

Oliver Stone: Yeah, I could.

Kara Swisher: Well, you’ve just made it, but —

Oliver Stone: I had to make it as a documentary because it’s very difficult to — you know, at one point we played, Josh and I played with the idea of doing a scenario about a female scientist, cause that was popular, a female scientist saving the world by her courage and so forth.

Kara Swisher: Through nuclear energy.

Oliver Stone: But, you know, that becomes kind of melodramatic. It’s not really a one-person issue. It’s really a global issue. It can’t be solved by the United States or one side. It’s going to be solved by a consensus in the world.

Kara Swisher: But the popular idea is that nuclear energy is dangerous, is that no matter what, it’s more dangerous than anything else.

Oliver Stone: It was bad. Yeah.

Kara Swisher: Was bad. So there are justified fears we’ve had, as you said. Sure. Chernobyl was the worst one. The UN estimates 4,000 deaths related to radiation exposure. But you and Mr. Goldstein fear it’s that it’s been blown out of proportion.

Oliver Stone: Totally. Compared to Bopal, the deaths at Bopal

Kara Swisher: Which is chemical.

Oliver Stone: Right. 1980 — was it 4? And then in 1975 we had the hydropower dam in China. 250,000 people died. So there are accidents in any industry. The airplane industry had accidents and they were very dramatic. Nothing compared to what the car industry was turning out, as Ralph Nader pointed out. In other words, what’s scary and what’s dangerous are two different things.

Nuclear energy is scary. But compared to the more mundane — oil, gas, coal — nothing compared to it.

Kara Swisher: So, Fukushima was another one. An earthquake and a tsunami hit in Japan, caused a nuclear disaster at an active power plant. As you point out, natural disasters are going to get more powerful and plentiful. So should we be more — not less — concerned about future Fukushima’s? Or do you think every energy source is at risk?

Oliver Stone: It’s funny that you call — everyone says Fukushima is a nuclear disaster. It isn’t. It was a tsunami disaster, as we had in the South Pacific. That plant was badly, had a low sea wall, and it was flooded. The generators were flooded, the sea wall was penetrated, but the containment structure held. There was a radiation leak, but again, realize it’s low-level radiation. People were checked out. Nobody died from radiation poisoning. People died from mismanagement. Hospitalization, hospitals were emptied and they rushed, but the Japanese government panicked and closed it down for quite a few years. So it’s just kind of a contagion of fear.

Kara Swisher: it would be like closing down planes if there was one crash.

Oliver Stone: Yeah, like closing down planes or banning knives. I mean, what’s a knife for. A knife is a wonderful instrument. We use it for hundreds of things, but it can also kill people.

Kara Swisher: All right. But you just said something which is — I think a lot of people would get their back up — where you and Goldstein said in an interview, and you just said it: you think that it’s better for nuclear if there were more accidents.

Oliver Stone: Well, I — that’s a form of saying “Yes, we’d get more used to it.” Because people get spoiled. They want zero tolerance. Zero tolerance, in any industry, is almost impossible.

Kara Swisher: So you’re saying accidents normalize the tech, in other words.

Oliver Stone: Accidents normalize. Yes, they do. And, I mean, think about the waste from nuclear compared to ammonia from agriculture—

Kara Swisher: Lot of fear about that.

Oliver Stone: Compared to arsenic, compared to lead, compared to mercury, which is just thrown into our landscape.

Kara Swisher: So that radioactive waste is safer than all the other things that come out of oil, gas, solar panels.

Oliver Stone: And then they talk about a hundred thousand years from now. Okay. Right. But you know, even so, it decays, it decays to almost nothing. Radioactive waste doesn’t move. It’s been over glamorized and over sensationalized and people can always say: What if, what if? But at a certain point you’ve gotta say, “Look, we gotta take the “what if.” Zero tolerance — it’s not gonna happen. We gotta build.”

Kara Swisher: All right, let’s talk about that. The cost. Plants getting built across the U.S. are costing twice as much as their budgets promised. While other countries have been able to do it cheaper, South Korea has actually lowered its costs. Talk about how we get costs down, specifically the rule of SMRs, which are small modular reactors which move around.

Oliver Stone: Well, that is the American way. We we’re building innovative companies, private companies, with the support of the DOE, the Department of Energy — exploring small modular reactors. Bill Gates has invested a lot of money. It looks very promising — what they call a natrium. Natrium is a salt water reactor. Don’t ask me to explain all the details. I’m not a scientist, but it looks good. It cuts —

Kara Swisher: Would you have one in your home when they get small enough?

Oliver Stone: Absolutely. In a second.

Kara Swisher: Interestingly, I had a discussion with Bill Gates about this, who was a big investor in nuclear technology — which of course will add to the conspiracy theories around Bill Gates, and the chips and the vaccines and everything else. But it requires startups to be doing this innovation in nuclear energy.

Oliver Stone: Well we make the point that startups are an alternative to General Electric, because General Electric bills on a big scale, and as it was explained in the film, their nuclear division is a small part of their overall business. They make turbines, they make drilling equipment. It is a huge company, so their motivation to do nuclear is limited. But there’s the small companies that don’t — that need, that do this full time, that this is their motive to begin with. That’s the companies that hopefully will make a breakthrough in America.

Kara Swisher: Yeah. Also, Sam Altman, who is the head of ChatGPT, also has a big fusion [company] he’s working on.

Oliver Stone: Fusion is also for the future, but not now.

Kara Swisher: That’s his great interest. You do explore France as a kind of nuclear energy gold standard. 70 percent of the country gets its energy from nuclear, but there’s serious costs [due to] climate issues. Last year, half of France’s plants were offline for repairs. Unusually high temperatures put more pressure on the plants’ cooling systems. The state funded nuclear power operator, EDF, is billions of dollars in debt. So is France really the shining example?

Oliver Stone: Yes it is. It’s a wonderful example actually, because it’s been working for 50 years. They built 57 reactors, and they’ve been delivering. And France had very low electricity costs and they had very little CO2. But, you know, the French system has to be repaired because it’s been in business for 50 years, at a low price. But there are pipes and corrosion and so forth and so on. But that’s part of the business you —

Kara Swisher: What they did should be the map.

Oliver Stone: Absolutely. And Russia too. Russia built — has 20 percent of its electricity coming from nuclear and they have built some of the finest reactors ever seen. They have this new fast breeder [reactor], which we saw at Beloyarsk in the Ural mountains in the center of Russia, that fast breeder uses its own waste.

Kara Swisher: Of course, it’s paid for by their gas and oil revenues.

Oliver Stone: Well no it’s paid for by the state. That comes from part of their — but gas is no good. Russia is definitely — it’s sad that they do it. But China’s the one that’s building the most nuclear right now. They are investing, according to what I read, $440 billion into building 125 or so new reactors. They already have 50 —

Kara Swisher: Because they need, they, they’ve promised to get to zero emission.

Oliver Stone: Well, that’s one thing. 2038, they will have like all these reactors in place and they’ll be building more. They have promised the president Xi has promised to go to zero emission, by 2060.

Kara Swisher: Right. So we’re not in China, we’re not in Russia, we’re not in France. In the U.S., how do you get politicians behind the nuclear vision in a bipartisan way? Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez recently went to visit the site of the Fukushima power plant and said she was there “to neither fearmonger nor sugarcoat.” So how do you get people in this country to be bipartisan about nuclear, especially when there’s oil and gas interest and coal interests? Joe Manchin just got it dropped into the debt ceiling bill — a coal plant.

Oliver Stone: Listen, I acknowledge it’s a huge problem to get people to change their ways, but the worst necessity is a mother of invention. The worse it gets, people will see. They know in their hearts that oil and gas are not disillusioned. But as the planet chokes, there will, there has to be change and people will realize maybe too late and they’ll be building nuclear as fast as they can by 2040 or even 2035. But as I said to you earlier, the nuclear business does not have a constituency. They’re not very good at promoting themselves. I talked to these people at Idaho Lab. They all wanna make the next solution, but they don’t have a clue as to how to advertise it like the oil people do or the coal people do.

Kara Swisher: Right.

Oliver Stone: Movies. Movies can help.

Kara Swisher: Let me ask you this. I think it’s a natural question: No nuclear company paid or invested in this movie?

Oliver Stone: No, no. This was done privately.

Kara Swisher: It was Participant [Media].

Oliver Stone: Participant helped us a lot. Jeff Skoll produced the Inconvenient Truth and he was anti-nuclear. We talked and two, three years ago he changed. He read everything he could on nuclear. He’s very bright man, much more scientific than I am, and he’s very happy with this film and wants it to penetrate — he’s doing everything he can to help us.

Kara Swisher: Okay, so you end the documentary on an optimistic note about the pace of technological innovation you’ve witnessed in our lifetime. Why so optimistic? You know, you’re very leaning into entrepreneurship. It’s a bit of a love letter to the nuclear —

Oliver Stone: You could say that at the ending, I want, you know — all I’ve seen in the last few years is dystopian stuff. The films, reading materials, it’s depressing. Everyone — I don’t understand why the movie business is just always about the death and destruction. I guess that makes money.

Kara Swisher: Yeah.

Oliver Stone: I really would like to see a change, and hope, given to the future. When this book I found — Bright Future is about hope and about changing the way we are doing our energy now. It’s doable. That’s what’s frustrating —

Kara Swisher: So, you know, it’s fascinating cause a lot of your movies are dystopian, whether it’s Wall Street, you know — Natural Born Killers really left me … was a bummer, was a fucking bummer, Oliver, I have to tell you.

Oliver Stone: Okay.

Kara Swisher: But I’m saying what shifted you to utopian? Because a lot of your films are darker, I would say. I don’t think they’re like dances in the park. I don’t —

Oliver Stone: No, I’m not known for a Disney approach.

Kara Swisher: Yeah, I don’t see Frozen here.

Oliver Stone: Believe me, I’ve always been an optimist because, sometimes you go to the darker places because you can handle it. You can take it and you don’t get depressed, but you can come out the other end and you’re better for it. That’s the truth about human existence. Suffering sometimes makes us wiser and better people. So the same thing applies in making, creating films like this. Somehow I have an innate optimism. Perhaps it comes from my mother. My father was a pessimist, actually, more than my mother — but my mother was really a believer in humanity. And I repeat that at the end of the movie because the scientist, Marie Curie, one of the greatest, brought us the discovery of uranium and what it could do, and Einstein and people, and even Eisenhower — as dark as it could get during the Cold War, he was still hoping that we could nuclearize our society. And we were close to doing that. I wish we had built more. But I’m optimistic. I’m an optimist.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

On With Kara Swisher is produced by Nayeema Raza, Blakeney Schick, Cristian Castro Rossel, and Megan Burney, with mixing by Fernando Arruda, engineering by Christopher Shurtleff, and theme music by Trackademics. New episodes will drop every Monday and Thursday. Follow the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

More From 'on with kara swisher'

- Ron Klain Still Thinks Biden Got a Raw Deal

- Gretchen Whitmer on Why She’s Still Confident in Biden

- AOC on Gaza, Insults, AI, and Whether Trump Will Lock Her Up