Earlier this year, Danny Masterson was found guilty of drugging and raping two women in 2003. Multiple other women have made similar, credible accusations against the former That ’70s Show star. When these women came forward in 2017, Masterson’s allies at the Church of Scientology allegedly made their lives hell, stalking them, harassing them online, and in one case, poisoning their dogs.

Masterson’s victims therefore found some catharsis last week when a judge sentenced the convicted rapist to 30 years in prison. After two decades of impunity, the serial sex criminal would not only face consequences but exceptionally tough ones.

Before Judge Charlaine F. Olmedo handed down her sentence, she had received letters making the case for leniency from several of Masterson’s celebrity friends, including his former castmates Ashton Kutcher and Mila Kunis. When these letters became public last Friday, many of Kunis and Kutcher’s former fans grew apoplectic.

In my view, there are sound reasons for the widespread outrage at Kunis and Kutcher, but also, a misguided one.

In both their pleas for leniency, and a subsequent pseudo-apology for causing pain to Masterson’s victims, Kunis and Kutcher pointedly decline to affirm their friend’s culpability in sexual violence. Rather, in places, they seem to tacitly vouch for his innocence. Kunis wrote that Masterson “demonstrates grace and empathy in every situation,” while Kutcher asserts that the convicted rapist “always treated people with decency, equality, and generosity.” Of course, it cannot possibly be true that a man who drugs and rapes women demonstrates grace in every situation, nor that he always treats people with decency.

In their apology video, meanwhile, Kunis and Kutcher legalistically avoided affirming Masterson’s guilt. The couple said that they did not mean to question “the legitimacy of the judicial system” or the “validity of the jury’s ruling,” but avoided saying that they do not question the truth of the victim’s allegations. This refusal to endorse the veracity of the proven allegations against Masterson was surely intentional. Kunis and Kutcher have been working with their friend’s legal team, which intends to appeal his conviction.

Thus, one could reasonably interpret Kutcher and Kunis as implying that someone like their friend could not have done what his victims have alleged. This is an ignorant and offensive sentiment. An adult in 2023 should understand that rapists do not betray their capacity for sexual violence in every interaction or relationship. It is entirely possible for a man to be both a good friend and a vicious sexual predator. Securing a conviction in a rape case is not easy. If a jury found beyond a reasonable doubt that your friend was guilty of sexual violence, then you should give that more weight than, say, his advocacy for 9/11 first responders when assessing his culpability. And if you think of yourself as advocate for victims of sexual violence — as Kutcher and Kunis both do — then you should affirm the veracity of proven rape charges when publicly commenting on a high-profile case.

So there were plenty of sound reasons for outrage at Kutcher and Kunis. But I think there was also an unsound one.

Although some social-media users objected to the specific content of Kutcher’s and Kunis’s leniency letters, others took exception to the very act of opposing “harsh sentencing” for a convicted rapist. And yet there is no inherent contradiction between concern for the victims of sexual violence and opposition to exceptionally long prison sentences for rapists.

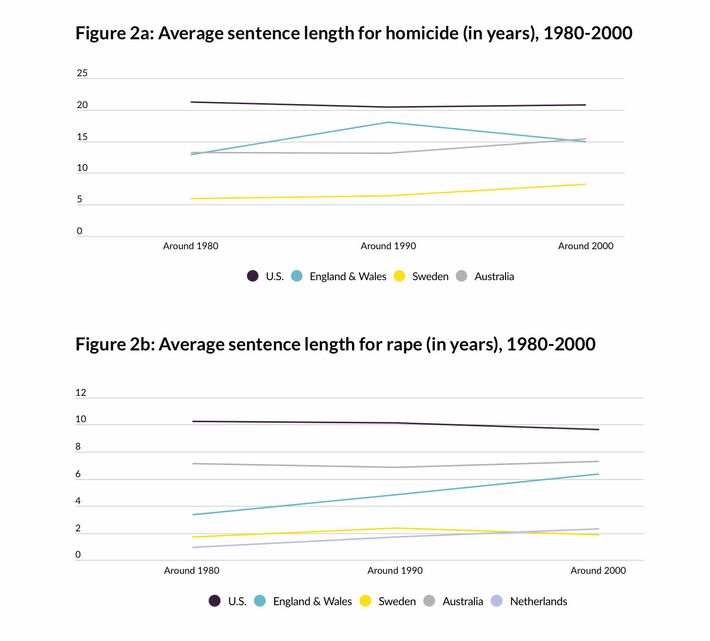

Today, the United States incarcerates a much higher percentage of its residents than any of its European peers. America’s exceptionally high homicide rate explains part of this discrepancy. The rest is largely attributable to our nation’s draconian sentencing practices. According to an analysis from the Council on Criminal Justice, between 1980 and 2000 the average imposed sentence for homicide in the U.S. was more than twice as long as in the Netherlands or Sweden. The average imposed sentence for rape was five times longer in the U.S. than it was in either of those European countries.

When one looks at actual time served, rather than initial sentence length, these disparities narrow a bit but still persist.

It is possible for a person to simultaneously believe that rape is a heinous and underprosecuted crime and that America should not impose much longer prison sentences on violent offenders than social-democratic nations do. To reject the latter view is to support the United States having an exceptionally large prison population, as more than half of 1,047,000 people in American state prisons were convicted of violent offenses.

Incarcerating a criminal can serve three purposes: to deter others from committing similar offenses, to incapacitate a lawbreaker who is liable to reoffend until they are rehabilitated, and to enact retribution on behalf of those harmed by the lawbreaker.

In my view, this third purpose is illegitimate. I believe that there is an ethical imperative to minimize unnecessary suffering. Imposing the suffering of imprisonment on offenders is justifiable to the extent that it reduces the sum total of human pain by discouraging others from committing harmful acts or preventing an unrehabilitated convict from reoffending.

But long sentences are neither necessary for — nor particularly effective at — deterrence. The criminological literature indicates that increasing sentence length does not reduce crime. What matters for deterrence is the certainty of apprehension, not the severity of punishment. This makes intuitive sense. Before an individual commits a crime, they are liable to consider their likelihood of escaping all consequences. It is not unusual for a burglar to look around for witnesses or nearby police before proceeding with a break-in.

By contrast, it would be unusual for such a person to Google their state’s criminal statutes to see whether their prospective course of action is punishable by ten years or 20 and then reason, Well, since it will only cost me a decade of my life instead of two, I’m going to go ahead with this.

Therefore, if we are concerned with deterring rape, our focus should be on increasing the certainty of apprehension by ending the outrageous epidemic of untested rape kits, investing more resources into the investigation of sexual violence, and increasing support for victims so as to enable everyone who wishes to come forward to do so.

The other legitimate function of a long prison sentence is incapacitation. Even if keeping rapists in prison for exceptionally lengthy periods does not deter others from committing similar offenses, it does render the incarcerated individuals incapable of menacing the public for a long period of time.

Yet a large body of research indicates that the vast majority of offenders age out of crime. Arrest rates for homicide and drug offenses peak at 19, while those for forcible rape peak at 18. Judging by arrest records, the typical criminal career ends after five to ten years. Once a person’s prefrontal cortex fully develops, they accrue more familial responsibilities, and/or they shed their youthful energy, they tend to start abiding by the law.

Long sentences are neither necessary nor sufficient for rehabilitating offenders. Sweden has some of the most lenient sentencing practices in the world. As of 2000, the average person convicted of homicide in Sweden served a little more than four years in prison, while the average person convicted of rape served a single year. And yet Sweden has a much lower recidivism rate than the United States. Only about 34 percent of those released from a Swedish prison reoffend within two years of reentry; in the United States, nearly half of freed convicts reoffend within that time frame.

This likely reflects the grotesque nature of incarceration in the U.S. American prisons are routinely overheated and infested by vermin. The food is often unhealthy and insufficient and sometimes dangerous. Most critically, the institutions routinely fail to protect their occupants from assault, rape, and murder. Each year, as many as 80,000 U.S. inmates are raped. Meanwhile, many prisons offer no education programs for the incarcerated, despite their demonstrable efficacy in reducing recidivism. Denied resources for self-improvement and subjected to the constant threat of bodily harm, many incarcerated people grow less capable of productively contributing to society as a result of their imprisonment.

For these reasons, it is entirely possible to make Americans safer from the threat of sexual violence and bring U.S. sentencing practices into line with European norms. If we investigated rape more aggressively, we would deter more offenders. And if we improved conditions in U.S. prisons, we would rehabilitate them more effectively over shorter time frames.

Many believe that the measure of our society’s concern for victims of sexual violence is the severity of their victimizers’ punishment. But if we do not want America to imprison an exceptionally high share of its population, then we need to reject this sentiment and find other ways to demonstrate our collective investment in the welfare of survivors.

I do not think that it was inherently wrong for Kunis and Kutcher to encourage a judge to put Masterson in prison for less than 30 years. It is reasonable to oppose such lengthy prison sentences on principle; Anders Brevik, who murdered 77 people, most of them children, was sentenced to only 21 years’ imprisonment, as Norway has decided that this should be the maximum sentence for any crime. Further, defendants are entitled to make an appeal for leniency. And if you are friends with a defendant and believe that they are capable of rehabilitation within a short time frame, it is legitimate for you to share that view with a judge.

The specific way that Kunis and Kutcher went about that task warranted criticism. But the act of writing a leniency letter does not. So long as we equate opposition to long prison sentences with indifference to the suffering of victims, we will live in an exceptionally incarcerated nation.