At a meeting with parents in May, Elizabeth Phillips, a longtime principal at P.S. 321, a highly sought-after elementary school in Park Slope, didn’t mince words about the new reading curricula being implemented across the city this fall by Mayor Eric Adams’s administration. Not only did she refer to the trio of options selected by Schools Chancellor David Banks and the mayor’s Cabinet as “three bad choices,” she also shared her plans to resist. “We are definitely pushing back against it,” she said, “and many principals in the district are. And our superintendent understands that we are not going to do it with fidelity, that we are going to keep doing what has worked for us.”

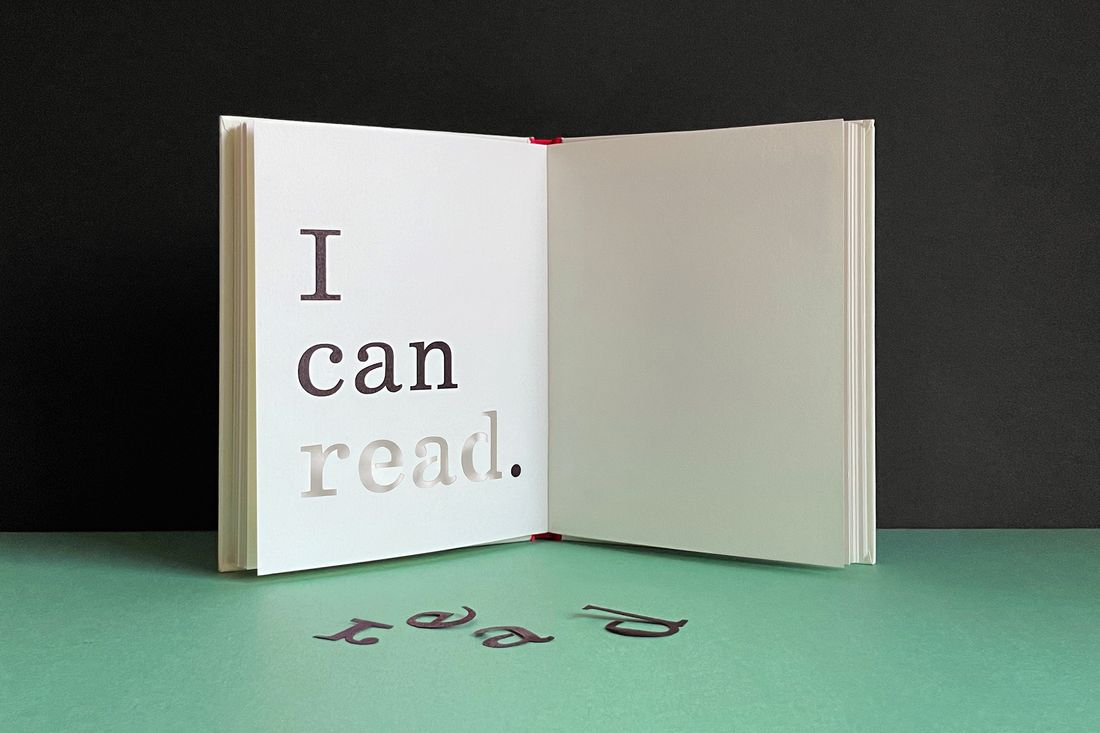

Phillips (who did not respond to interview requests; the spring meeting was recorded) is a devotee of “balanced literacy,” an approach to teaching kids to read that had been the prevailing ethos in New York City schools for roughly two decades — until it came crashing down last year when heightened scrutiny caused the method’s once-revered leader, Lucy Calkins, to concede that it was fundamentally flawed. Specifically, critics said kids were falling behind because they didn’t know how to sound out words. Instead of phonics, Calkins’s program pushed a cuing method that instructed students to look at the first letter of a word, then to a picture on the page, and consider the context and piece it all together. But this technique relied on students having enough background knowledge to make the proper inferences as well as the ability to process language without difficulty. As a result, many kids weren’t actually reading. They simply became really good at guessing.

Last year, Adams — who is dyslexic and has been open about struggling in school as a child — mandated that New York City public schools supplement early-reading instruction with phonics. The change was largely welcomed; many school leaders, including Phillips, had already recognized the need and sprinkled more phonics into their lessons. But in the spring, Banks announced a much more sweeping change: Over the next two years, all New York City public-school districts must implement one of three reading curricula that follow “the science of reading,” an approach based on long-standing research showing that kids become stronger readers when there is an early focus on phonemic awareness (the ability to identify sounds, like rhyming) and phonics (breaking down words by letter sounds and syllables). Calkins’s curriculum, formally titled Units of Study, which she revised to include more phonics as part of her public mea culpa more than a year ago, did not make the cut. On September 1, Columbia University’s prestigious Teachers College — which championed her for decades — announced that Calkins had stepped down as director and that the program she founded was being dissolved to make way for a new Advancing Literacy unit that aims to “foster more conversations and collaboration among different evidence-based approaches to literacy.” In other words: It’s following the science too.

Columbia’s announcement marked a sharp pivot, as did the move by the Adams administration. Balanced literacy has been taught throughout the U.S., but no city bought in more than New York — home to Calkins, Teachers College, and, most crucially, the largest public-school system in the country with more than 1 million students. A 2019 curriculum survey of nearly 600 public elementary schools in the city, obtained by Chalkbeat and The City, showed that almost half were using Units of Study, making it the single most popular choice “by far.” The results have been bleak: State tests from 2022, the most recent year for which data is available, showed that only 49 percent of the city’s third- to eighth-graders were considered proficient at reading and writing for their grade level — not out of step with national numbers but still alarming. Black and Hispanic students fared even worse; just over a third were proficient. When Banks announced the curriculum mandate, he called the current state of literacy “the educational crisis of our time.”

The rollout of the new curricula begins this month for almost half of the city’s 32 school districts. The program has been named NYC Reads and will cost an estimated $35 million in its first year. Educators who advocated for the change and parents who have been paying attention — including those who had time to listen to the podcast Sold a Story, which detailed the pitfalls of balanced literacy and reverberated out of AirPods at pickup and drop-off last year — are celebrating.

But there’s also anxiety. Teachers, barely recovered from the stress of the pandemic, fear that if the program doesn’t achieve quick success, they will be blamed. Others resent being told from up high what they should do in their classrooms. And there’s suspicion, particularly among opponents of the mandate, that the Adams administration is simply swapping one trend in education for another, potentially leaving schools in a lurch if he doesn’t get reelected.

NYC Reads comes at a time when the city itself is at a tipping point. The population remains below pre-pandemic levels while rents soar. Many office buildings, a major tax generator, stand as post-pandemic ghost towers. Violent-crime rates are down and subway ridership is up, but New Yorkers are still wary. For families on the fence about staying here, access to a quality public education is a major factor. After all, what good is a city that can’t teach its children to read?

The debate about the best way to help children learn to read goes back more than 100 years, but an overwhelming body of data has shown the benefit of having kids sound out letters and words. One of the largest analyses of such studies is a 2000 report by the National Reading Panel, which found that phonemic-awareness instruction helps kids learn to read and boosts comprehension, while teaching systematic phonics “makes a bigger contribution to children’s growth in reading than alternative programs providing unsystematic or no phonics instruction.” President George W. Bush used the report as the foundation for his own reading initiative, which stressed phonics for early readers.

Even that report left the door open for proponents of balanced literacy, noting that phonics “should be integrated with other reading instruction to create a balanced reading program.” Plenty of educators listened to this part loudly — despite the fact that those advocating for more phonics were never saying phonics only. “When I started on this journey, I was like, Phonics? That’s what George Bush wanted. Phonics? That’s what happens in red states,” says Danielle, a teacher in New York who, like many of the two dozen people interviewed for this article, requested we use her first name out of concern for professional consequences.

Calkins’s curriculum was an antidote to what some educators perceived as the dry approach advocated by the Bush administration. Her early books — The Art of Teaching Reading and The Art of Teaching Writing — appealed to educators in part because she treated their profession as a craft and the children as whole people. Michael Gervais, a teacher in Fort Greene who studied under Calkins, says that even though he has long been skeptical of her approach, “she encouraged me to always listen to children in a deeper way. She really nurtured that.”

Getting kids excited about reading was an easy idea to get behind. Teachers who liked Calkins’s curriculum found it both more engaging than having kids repeat sounds over and over and, several say, much easier to teach. As one puts it, “Phonics is very much about ‘This is correct, this is incorrect.’ Balanced literacy is very much like, ‘Let’s let the child do a self-discovery to make sure they can make a stronger connection.’”

But the kids also needed to learn to read. Maggi Padua, a New York City public-school teacher who retires this month after 30 years in the classroom, maintains, “For years, I’ve been saying, ‘This is crazy that they’re asking students to guess the word.’” Teachers who started their careers in New York City describe being confused by the method, but also trusting it. “I was like, What? We just tell them to look at the pictures?” says Ellie, also a public-school teacher in the city. “But I was also like, It’s Columbia, so it must work, right?” Kate Gutwillig, who has taught in New York City public schools for 25 years, balks at what she calls “this sort of reverence” with which the city’s school officials used to speak about Calkins: “There was always this mystique. ‘Ooooh, listen, these teachers are going off to the Adirondacks to her cabin to write curriculum.’ Ooh wooow.”

Teachers express guilt about all the students who might have fallen through the cracks over the years. An early indicator of dyslexia, which affects as much as 20 percent of the population, is when a child has trouble rhyming — one of the first skills taught in phonemic awareness. With balanced literacy, the red flags were too easy to miss. Students who spoke a first language other than English were also at a disadvantage. For years, Jackie Rosenberg, co-founder of the private tutoring company City Kid NY, taught second grade at a New York City public school where many of her students spoke Urdu, Arabic, Bengali, or Spanish. When she tried to teach them with Calkins’s approach, her students lacked the English vocabulary to accurately guess. Imagine someone pointing to an image of an object and asking you to say what it is in a language you barely know.

A chief complaint about balanced literacy is that it works best for kids who have a leg up — the ones surrounded by books at home, who are also exposed to a range of experiences at an early age. These are often the same kids who, if they do struggle, have parents who can buy them extra help. Craig Selinger, owner of the tutoring service Brooklyn Letters, says there has recently been “a substantial surge” in demand for his company’s literacy tutoring. Rosenberg says City Kid clients typically pay anywhere from $6,500 to $12,000 per school year for tutoring.

“It makes me really angry for the families that I teach, the families that don’t have the resources,” says Ellie, who hired a tutor to help her own daughter with dyslexia when she couldn’t get support from her local public school. She has since enrolled her daughter in a charter school and says she’s weary of parents in her upscale section of Brooklyn who wax poetic about the neighborhood school while supplementing their kids’ education. “It’s all so contradictory. It’s like, ‘I’m at this school because I want diversity, but I’m going to then secretly give my kids all the things they need and not push the school to do that.’” When teachers sounded the alarm about balanced literacy, they say they were told to troubleshoot with a list of interventions that often didn’t work or they were told that outside factors were at play. “The emphasis was on poverty and racism, and we were told those were the reasons kids weren’t learning — not the curriculum,” says Lindsay, who worked in New York City charter schools for over a decade.

As the new school year approached, the mood around the rollout of NYC Reads could be described as tentative excitement. Thousands of teachers had signed petitions calling for a more evidence-based curriculum. “The reality is that teachers want this. They’ve asked for this,” says Marielys Divanne, executive director of the New York chapter of Educators for Excellence, an organization that advocates for teachers’ input in creating education policy. “The anxiety is that that support won’t be there.”

Last spring, teachers in districts that are part of the first phase of the rollout underwent training on the three curricula options: Into Reading, Wit & Wisdom, and EL Education. All but two districts chose Into Reading, for which teachers received anywhere from nine to 14 hours of training via webinar. New teachers and those not able to attend were offered training in July and August, but the school system can’t force educators to work over the summer. Throughout the school year, teachers will also receive a minimum of eight in-person training sessions. Funding for these will come from the $35 million central budget allotted for phase one of the initiative, according to Carolyne Quintana, deputy chancellor of teaching and learning for New York City public schools. She says some schools are hiring extra coaches at their own expense — those with the funds to do so, of course.

All three of the new curricula meet both expectations for usability and standards for what students should know and be able to do at a particular grade level, per the nonprofit EdReports. “Each of these were highly reviewed and nationally recognized,” says Quintana. But she provides minimal detail on the process of selection and on why these curricula stood out among all the available options. EL was chosen in part for its “really strong alignment to the phonemic-awareness supports,” she says. Into Reading was chosen because “it has resources and guidance not only for teachers but for parents so they can help their kids at home,” as well as a Spanish component, Ariba, for students who learned Spanish as their first language. And Wit & Wisdom has what Quintana describes as a “large range of reading materials.”

There are teachers who remain skeptical of the new curricula even if they support a shift to the science of reading. Several say they are worried that these curricula haven’t been properly vetted. Out of all the options available, they want to know, Why these three? One principal surmises that Into Reading is so popular because it was free during the pandemic and some schools were already using it, and because the publisher is able to scale for such a massive school system. Another says it’s difficult to up and change a curriculum that has been in place for years because it becomes part of a school’s culture. There’s an emotional attachment.

One Brooklyn principal whose district is using Into Reading describes the training she received in June as an “infomercial.” Was it adequate? “I feel like it’s asking, ‘Is Lionel Messi prepared to score goals at his new soccer team?’” she says. “But meanwhile, there’s no ball, no stadium, no fans. I feel like the bigger question is like, What investment have we made in ensuring all teachers have what they need to make sure all students learn to read?”

In May, NYU Steinhardt’s Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools declared Into Reading to be “culturally destructive” owing to “superficial visual representations to signify diversity” and “one-sided storytelling that provided a single, ahistorical narrative.” More than 80 percent of students in New York City public schools are children of color. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, which publishes Into Reading, refutes the NYU findings. “They took snippets of pieces of content that in no way represent the corpus of what’s in the program,” says Jim O’Neill, the head of core curriculum at HMH.

Its most convincing selling point may come straight from the city’s classrooms: An analysis by HMH of more than 5,000 students in grades two through five who used Into Reading or HMH professional supports in the 2021–22 school year found a 24 percent increase in students reading at or above functional grade level and a 42 percent decrease in students performing two or more years below grade level.

Quintana says there are no plans, for now, to allow exceptions for schools that don’t want to make the switch, including in phase two. She expects they will try anyway — and if Phillips, the principal of P.S. 321 who was outspoken about the change this spring, is any indication, Quintana is right. One principal who supports the curriculum mandate understands the resistance to it: “We were told Teachers College was the best thing since sliced bread, and so now we are supposed to say it’s not because you’re telling us it’s not? Not that I agree with it, but it’s not fair to say, ‘You’re still doing Teachers College? I can’t believe it!’”

It could be three to five years before Adams’s big gamble can pay off. That’s how long educators say it takes to really get comfortable with a curriculum and know whether it’s working. Some educators in the first phase of the rollout are envious of the districts in phase two, which have more time to select a curriculum and the benefit of observing how things go this year. Others say there’s no time to waste. “A year’s wait for a kindergartner to second-grader is a lifetime in terms of being able to learn to read,” says Danielle, the teacher. “It’s not pivotal in the scheme of a curriculum, but it’s pivotal in the life of a child.”

More on schools

- Did J.D. Vance Say School Shootings Are a ‘Fact of Life’?

- Marking 70 Years of White Flight From School Integration

- The Rutters of Athens County