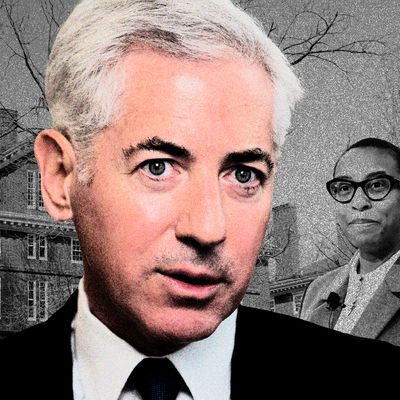

Bill Ackman, the billionaire hedge-fund manager, declared defeat late Monday as it became clear that his weeklong campaign to force Harvard president Claudine Gay to resign had failed. Harvard’s governing board announced on Tuesday morning that it stood firmly behind its leader, though it added that her response to the Hamas terror attacks on Israel had fallen short.

It was the end, at least at Harvard, to a stunning saga that has rocked the academic world in recent days. Suddenly, several Ivy League institutions have found themselves on the receiving end of tactics developed and routinely used by Wall Street’s top activist investors — a hard-charging category of hedge-funders who acquire shares in a company and then typically try to change the management and corporate strategy through an unrelenting pressure campaign. Previously, those measures had been deployed only against large, publicly traded companies. Ackman, an activist investor and founder of the hedge fund Pershing Square, has a well-known playbook for pressure campaigns and attempting to oust CEOs, having built much of his reputation — and wealth — by using aggressive public messaging to increase the value of his big investments. A notable success in doing so was a long position in Wendy’s that resulted in a large profitwhen he browbeat the company into a spinoff of Tim Hortons. It doesn’t always work, of course: A big bet against Herbalife — he went to extraordinary lengths to argue that the supplements company was an illegal pyramid scheme — resulted in a loss for Ackman of an estimated $500 million.

And at the University of Pennsylvania, the campaign — in which Ackman was joined in his criticism by high-profile financiers and donors including Marc Rowan, CEO of the large private-equity group Apollo — worked as intended, resulting in the resignation this past weekend of the school’s president, Liz Magill.

But Harvard, of course, was a failure for Ackman and those same activist methods. His inability to oust Gay now looks like a lesson in the limitations of an activist campaign in the academic world, outside its usual confines in public markets. There, the tactic has a reasonably high rate of success in the hands of someone like Ackman, who is able to appeal to other stockholders on a purely financial basis: Vote with me, an investor says, and we will all get richer. But a university has no stock price. Instead of shareholders, it has an array of stakeholders, including alumni, students, and faculty. At least for an immensely wealthy institution like Harvard, their concerns for the university’s future are not primarily tied to a financial outcome but rather centered on how its actions reflect their personal values and feelings and affect the school’s overall reputation.

Harvard, then, had to weigh the risk that firing Gay — its first female Black president — wouldn’t be received well by those communities, especially when the person spearheading the firing campaign was an icon of the capitalist one percent. Some on Wall Street grasped this early. “Frankly, if Harvard fires Claudine Gay, it will look like Harvard is capitulating to Bill Ackman and other wealthy donors. I think the more public calls for her ouster from wealthy white men actually make it less likely that Harvard will fire her,” Whitney Tilson, a former hedge-fund manager who now runs Empire Financial Research and who attended Harvard undergrad with Ackman, told me before the university’s board meeting. Tilson was withholding judgment on whether or not Gay should keep her job. “The optics of that could not be worse,” he added.

Despite the furor on social media, there were reasons all along to think she might escape the same fate as her UPenn colleague Magill. Besides representing a shattering of barriers for Black women in leadership at Harvard, Gay had just begun her position in July. The perception was making even some versed in the unsentimental methods of Wall Street and business uncomfortable. “It sort of feels that the mob is at work right now, and my general knee-jerk reaction is I don’t like mobs,” Tilson told me. “There’s also something in the back of my mind that I want to be very, very, very, very careful about: Would the response and the mob and calling for her head be the same if she were one of the two Ivy League presidents who are a white man?”

As Ackman’s calls for Gay’s resignation grew louder, a split among Harvard alumni on Wall Street grew deeper, and on Sunday evening, dozens of Black alumni held emergency meetings to discuss how to express their dissent. In the wee hours of Monday morning, they crafted a petition to support Gay and sent it to the Harvard Corporation (the university’s chief governing body) at 8:30 a.m.; by the afternoon, nearly 1,000 “concerned Black alumni and allies” had signed it. “You have a vocal, outspoken person who is relentless and is leading us in the wrong direction,” said one Harvard alumnus who works in finance and who attended the meetings. “Ackman’s motives may be right, but his tactics will end up dividing the community, as opposed to uniting them when they really need it.”

Some of the signatories especially objected to Ackman’s criticism of Harvard’s diversity, equity, and inclusion program, which Gay had championed and which was now being blamed as the source of, or even equated with, antisemitism on campus. “These extraordinary leaps from people who are as smart as they come should make us all pause,” said Judith Aidoo, a Harvard alumna and investment banker who signed the petition. “To me, this is bigger than Dr. Gay, and I don’t think she should resign — under any circumstances. If we all get branded as DEI hires, somebody with her intellect and her standing at the university, and Bill Ackman says she’s not good enough to hold that seat, that, to me, is the reason I’m asking her to stay. Not even to prove him wrong but to prove people like him wrong. I expect her to be human and teachable and grow into her position. So I’m asking for the same grace that would be given to any other human be given to her as a Black woman.”

When Ackman took aim at Harvard, where he attended both undergrad and business school, his campaign started in a similar way to the battles he has waged against corporations with letters and entreaties to meet. And at first, the hedge-fund manager seemed to be winning. He had been publicly criticizing Harvard for its handling of campus antisemitism since Hamas terrorists attacked Israel on October 7, and in late November he saw an opportunity to give Gay an offer he thought she couldn’t refuse. Gay was scheduled to testify in front of Congress alongside the presidents of MIT and UPenn on the morning of December 5, which would force her to miss a screening the night before at Harvard of the footage of the Hamas attacks, hosted by the Israeli ambassador to the U.N. To make it possible for her to attend both, Ackman offered to send his private jet to Boston to fly her to D.C. right after the screening; he would personally escort her, serving dinner on the plane. “What better way for her to show the seriousness with which she is taking the issues around October 7th and antisemitism?” Ackman wrote on X. “I wanted, among other things, to help prepare her with the likely questions she would receive.”

Gay politely but crisply declined. The decision primed a horde of Harvard alumni, particularly from Wall Street and the business world, to doubt Gay’s leadership and commitment to protecting Jewish students, even before her performance at the hearing created uproar. “It was just a blow-off. It was a slap in the face of Harvard’s Jewish community, and that’s why it was an epic fail,” Tilson said of Gay’s decision to skip the film screening.

Less than a week later, Ackman was leading a throng demanding Gay resign after she equivocated in a congressional hearing when asked whether she would consider calling for the genocide of Jews a violation of Harvard’s code of conduct, saying, “It can be, depending on the context.”

The hearing likely would not have generated the firestorm it has if Ackman had not cut the now-infamous three-and-a-half-minute exchange between Representative Elise Stefanik and the presidents from the four hours of testimony and posted the clip to his X account. “They must all resign in disgrace,” Ackman wrote. “She has to go now,” he followed up soon after, referencing Gay. Other prominent figures joined the chorus. “The cowardly and unprincipled responses show them each to be unfit to lead,” Dan Loeb, the billionaire and CEO of the hedge fund Third Point, wrote in reply to Ackman, though he seems to have since deleted the comment.

By the end of last week, Ackman’s video clip had received more than 100 million views; by Saturday, the president of Penn had resigned; Saturday Night Live had spoofed the hearing with a skit for its cold open; and by Sunday evening, the calls for Gay to step down had grown deafening with many Harvard alumni spending the weekend debating whether she deserved to keep her job. On the betting site Kalshi, the odds of Gay being ousted by 2025 spiked to at least 81 percent.

In a larger sense, Ackman had been building the intensity of the activist techniques he used against Harvard’s leadership for weeks. In the days after the Hamas attacks, he called for the names of all the students who belonged to student groups that signed a controversial statement blaming Israel for the violence so that he and other CEOs could blacklist them from their firms. (Critics accused Ackman of trying to dox the students, some of whose faces were later displayed on trucks driving around campus that labeled the students as antisemites.) Ackman was also incensed when Gay did not respond to some of the letters he sent her — a fatal mistake when dealing with any activist investor, as any of Ackman’s CEO targets would have learned.

“So yes, I’m an activist, but my activism today is probably not in the corporate boardroom. It’s on campus,” Ackman told David Rubenstein, the co-chairman of the Carlyle Group, in an interview that aired last week.

One critical difference between the campaign at UPenn that led to the ouster of the university’s president and the demands for Gay’s resignation at Harvard is that several major Pennsylvania donors publicly withdrew or threatened to pull large donations, which so far has not happened at Harvard. Top Harvard donors, including hedge-fund managers Ken Griffin and Seth Klarman, communicated to the university’s leadership that they wanted to see it do more to combat antisemitism — Griffin told the New York Times he’d called the head of the Harvard Corporation, Penny Pritzker, while Klarman co-signed an open letter with Mitt Romney and other prominent Wall Street alumni. But neither said they would stop writing checks to Harvard, at least not publicly. (Klarman declined to comment; Griffin did not respond to a request for comment.)

Even Ackman said he has not threatened to stop donating. “I haven’t made any statements about economic support for Harvard,” he told Rubenstein. “I don’t want to threaten one way or another. That’s not my kind of approach.” Still, he claimed on Sunday that he was “personally aware of more than a billion dollars of terminated donations from a small group of Harvard’s most generous Jewish and non-Jewish alumni.” While several Pennsylvania donors made public announcements that they were pulling their contributions, Harvard’s donors, in contrast, seemed to be doing so quietly, perhaps preferring to let their money speak for itself.

The board that governs Harvard met on Monday to decide Gay’s fate, and by late evening Ackman was conceding defeat. Ackman was also coming to realize a point that skeptics like Tilson had made: “One of the factors that made it challenging for the @Harvard board to fire Gay was that they were concerned it would look like they were kowtowing to me,” he wrote on X.