Blue America is an increasingly affluent nation. In every presidential election from 1948 to 2012, white voters in the top 5 percent of America’s income distribution were more Republican than those in the bottom 95 percent. Now the opposite is true: Among white Americans, the rich voted to the left of the middle class and the poor in 2016 and 2020, while the poor voted to the right of the middle class and the rich.

More broadly, the Democrats now represent 24 of the 25 highest-earning House districts in the country. This is a striking departure from 20th-century norms, when Democratic congressional districts were poorer on average than Republican ones.

The Democrats’ growing strength with affluent professionals has left them with a motley coalition, one that unites McMansion owners with rent-burdened tenants, and tech moguls with Uber drivers.

Observers of this realignment have long predicted that it would lead Democrats to move right on economic issues (in deference to their growing reliance on wealthy suburbanites) and center identity politics in both their messaging and policymaking (to appease working-class nonwhites who might otherwise resent the party’s rightward drift on economics). Indeed, some on both the left and the right assert that this ideological shift has already occurred. After all, various social issues — from policing to immigration to youth gender medicine — take up more bandwidth in our political discourse than more mundane questions of fiscal policy. And in 2016, Hillary Clinton demonstrated that identitarian appeals can abet economic moderation, as she portrayed Bernie Sanders’s social democratic politics as grossly insensitive to the peculiar needs of women and nonwhites.

Further, there is a large body of political-science literature indicating that European center-left parties have in fact moderated on economic policy, and shifted their focus to social issues, as they’ve grown more reliant on the votes of educated professionals.

Thus, all available evidence indicates that the Democrats are becoming a more culture war–focused, economically moderate party — except, that is, for what Democratic politicians actually say and do.

That the Democrats have remained stubbornly focused on progressive economic reform has been apparent for a while now. But in a new paper, “Bridging the Blue Divide: The Democrats’ New Metro Coalition and the Unexpected Prominence of Redistribution,” the Yale political scientist Jacob Hacker and his colleagues quantify that resilient commitment.

Hacker and his coauthors seek to gauge both the progressivity of the Democratic agenda over time, and the degree of emphasis that the party places on economic issues in both policymaking and messaging.

Examining the party’s presidential platforms over time, they find that the Democrats now hold more progressive stances on social insurance and labor policy than at any time since 1984, with the party moving markedly leftward on economics since the mid-1990s. (Ironically, the modern high point of Democratic economic conservatism coincided with modern high point of working-class support for the Democratic Party; in 1996, President Bill Clinton assembled the most working-class Democratic coalition of the past four decades while campaigning on a centrist economic agenda.)

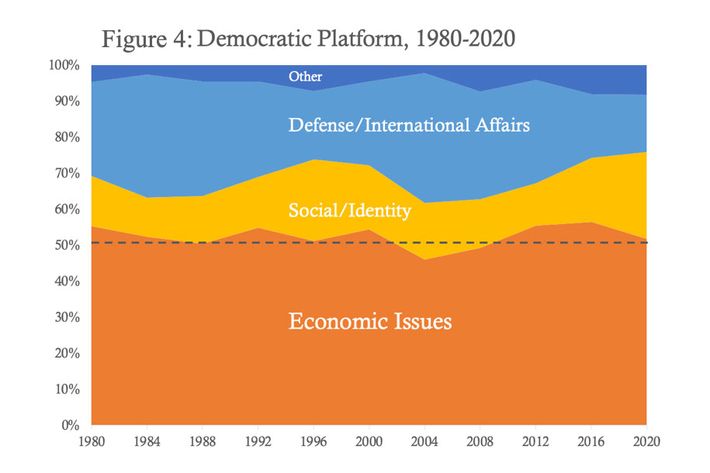

To measure the relative emphasis that Democrats place on economics, meanwhile, Hacker & Co. looked at the proportion of the party’s platforms dedicated to economic issues, the content of Democratic leaders’ posts on Twitter, and the party’s actual legislative priorities during Joe Biden’s first two years in office. They find that “social/identity issues” have claimed a growing share of Democratic platforms since the mid-1990s. Yet this increase has been modest in scale and has come primarily at the expense of attention to foreign policy. By contrast, since 1980, economic issues have taken up a relatively stable share of Democratic platforms and still comprised a majority of that document in 2020.

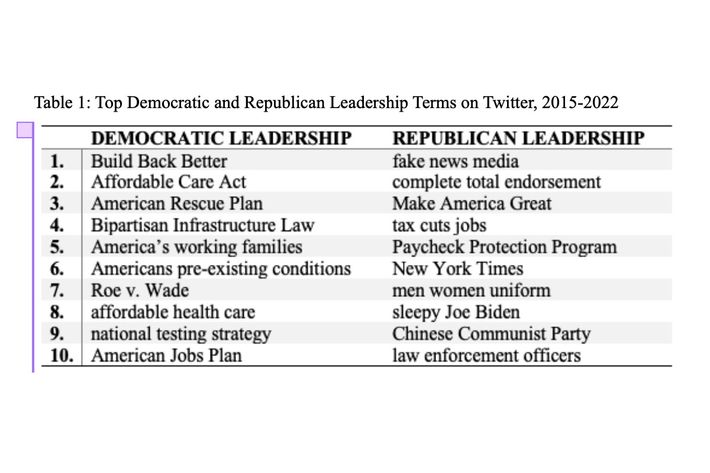

Twitter is (was?) a platform disproportionately frequented by young, socially liberal voters. Therefore, if Democratic messaging was going to emphasize identity politics over economics in any venue, it would plausibly be there. Yet when Hacker examined the phrases most frequently tweeted by Democratic leaders from 2015 through 2022, he found that eight of the top ten referred to economic issues, with the other two referencing public health and abortion. This stands in marked contrast to the social media habits of Republican politicians over the same time period. Just two of the top ten phrases most often tweeted by GOP leaders referred to economic issues.

Hacker and his coauthors also looked at the Twitter messaging of congressional Democrats writ large, and found that the party’s rank-and-file is nearly as focused on economic matters as its leadership. What’s more, Democratic officials who put greater emphasis on social issues in their Twitter messaging tended to do so from a moderate direction, with representatives from wealthier districts posting many positive sentiments about the police and the military. By contrast, members of the Congressional Progressive Caucus tweeted about their party’s economic proposals more than any of the other subgroups of House members that the study examined.

Finally, and most consequentially, the paper finds what any honest observer of the Biden presidency already knew: that Democrats’ legislative efforts in 2021 and 2022 were overwhelmingly focused on economic issues, and that Biden’s Build Back Better agenda was more progressive in its redistributive implications than any Democratic president’s since Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society.

Of course, Build Back Better never made it into law. And although historically notable for its climate investments, the Inflation Reduction Act was utterly unremarkable in its provisions for social insurance. Yet Hacker and his colleagues persuasively argue that Build Back Better’s failure had less to do with the economic conservatism of upscale Democratic voters than with the party’s slim congressional margins. After all, the primary impediment to Biden’s agenda in the Senate was Joe Manchin, who represents one of the poorest states in the union.

There has been widespread speculation that, although Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema were the only senators to visibly oppose Build Back Better, a larger group of moderates were hiding behind them. In extensive interviews with Democratic elites, however, Hacker and colleagues found widespread denial of that theory. As one high-level Democrat told them, “There were a solid 48. And Sinema was gettable. Most Democrats were working together for a common purpose.”

The fact that Sinema’s opposition has proven politically damaging (if not ruinous) for her lends credence to this assessment. Even though she represents a swing state, and relied heavily on the support of college-educated voters for her election in 2018, Sinema’s obstruction of Build Back Better caused her approval with both Arizona Democrats and independents to collapse. It seems clear then that Democratic lawmakers reliant on affluent, suburban voters do not face a political imperative to oppose progressive economic policies. Rather, if Democratic leaders rally behind such policies, lawmakers who from purple areas have a strong incentive to support progressive redistribution.

All this said, it is still arguably the case that the novel class composition of the Democratic electorate prevented the party from dramatically expanding the welfare state. If so, however, this was because the party’s eroding support among working-class voters has put it at a great disadvantage in Senate elections. Since the typical U.S. state is less college educated than the nation as a whole, the Senate inherently favors whichever party’s support is more disproportionately non–college educated. Thus, part of the reason why Manchin and Sinema were in a position to veto the Build Back Better agenda was that the modern Democratic coalition is geographically inefficient, not least due to the party’s growing dependence on educated professionals.

Further, although upper-middle-class voters haven’t yet pulled the Democrats right on economics, they might well do so in the future. As Hacker and his coauthors note, the Democrats have already made significant concessions to the material interests of the well-off. Although the party’s presidential platforms have grown more progressive on social insurance and labor since the mid-1990s, they’ve actually grown less progressive on taxation since then. During the 2020 campaign, Biden famously forswore tax increases on any household making less than $400,000 a year.

The party was able to cobble together a profoundly progressive fiscal agenda anyway, through a combination of high taxes on the superrich and budget gimmicks. These methods were sufficient to “pay for” trillions in new social spending, thanks in part to the American upper crust’s extraordinary share of national income.

And yet, the true constraint on spending is not scarce dollars, which the federal government can print at will. Rather, the constraint is scarce labor and real resources. If Congress creates more demand for such resources (through new spending) than it eliminates (through new taxes), then it puts upward pressure on prices. This makes financing new social welfare programs exclusively through taxes on the superrich problematic. Since billionaires do not actually spend their marginal income, raising taxes on them does not necessarily have any impact on the economy’s demand for real labor and materials at a given point in time. If you take $2 million from Jeff Bezos, you will not force him to reduce his consumption at all. If you then transfer those $2 million to a bunch of working-class households, then total demand for goods and services in the economy will rise.

During the 2010s, when the Democrats’ modern agenda was formulated, this point was of little consequence. With the economy perennially understimulated, there was no need to think seriously about what soaking the superrich can and cannot accomplish. But in the wake of the post-COVID inflation, the limits of “wealth tax populism” are more apparent. If Democrats implemented Joe Biden’s American Families Plan in full, it would likely have spurred considerable inflation. If you increase the disposable incomes of working-class parents through a child allowance, while subsidizing demand for child care and elder care — and “pay for” these measures through taxes on the superrich that do not actually reduce their capacity to consume — then total economic demand is liable to outrun supply. By contrast, if you pay for such measures by raising taxes on the upper middle class, then affluent households will be forced to pare back their consumption. That in turn will free up workers and resources for redeployment in publicly subsidized care sectors, as well as for satisfying rising consumer demand from working-class families (who will now be able to afford to buy more things).

It is possible that the post-COVID inflation will dissipate, the economy will grow understimulated, and the Democrats’ inflationary fiscal agenda will become unproblematic again. Yet even in that scenario, tight constraints on the party’s progressive ambitions will remain. It is simply not possible to sustainably finance a Western European-style welfare state, in a rapidly aging country, without raising taxes on anyone who earns less than $400,000 a year.

Separately, it is surely true that the Democrats have moved markedly leftward on social issues in recent decades. And this movement has had the effect of raising the salience of the culture wars in American politics. Nevertheless, it is not the case that the Democratic Party has been actively trying to increase the salience of social issues, so as to deflect from its internal class tensions.

The popularity of that idea is a by-product of media dynamics. On social media, political stories that center identity and culture war controversies tend to generate more engagement than those about mundane questions of spending and regulation. Democratic commentators, and ordinary posters, therefore have an incentive to focus on social issues and/or put an identitarian spin on economic ones. Meanwhile, right-wing media works round the clock to amplify cultural issues that cleave progressives from the median voter. It does this in part by casting left-wing activists and pundits as representatives of the Democratic Party, even when the former’s positions are repudiated by the latter.

In reality, it is the Republican Party that seeks to raise the salience of cultural issues, so as to obscure the material conflicts between its working-class voters and plutocratic donors. The Democrats, meanwhile, typically seek to deflect attention away from their most progressive social commitments, and to center their economic proposals. This divergence reflects the two parties’ disparate political imperatives. Since America’s political institutions systematically underrepresent the Democrats’ urban and highly educated base, the party must win a great many right-leaning voters in order to wield federal power. Further, the party’s reliance on minority voters in general, and Black voters in particular, gives it an incentive to avoid polarizing politics along lines of racial identity. Republicans, by contrast, have more latitude to indulge their base’s divisive cultural causes, thanks to their coalition’s structural advantages. And as the party of America’s racial majority, they also stand to benefit from increases in race-based voting. These facts, combined with their commitment to deeply unpopular fiscal priorities, give the GOP an incentive to foreground social issues.

Perhaps, the Democrats will one day be a party of fiscally conservative cultural warriors. For now, though, that title still belongs to the GOP.