Over the last four months, TikTok has undergone a rapid change, arguably the biggest in its strange short history: The most influential social app of its time is being turned into a store.

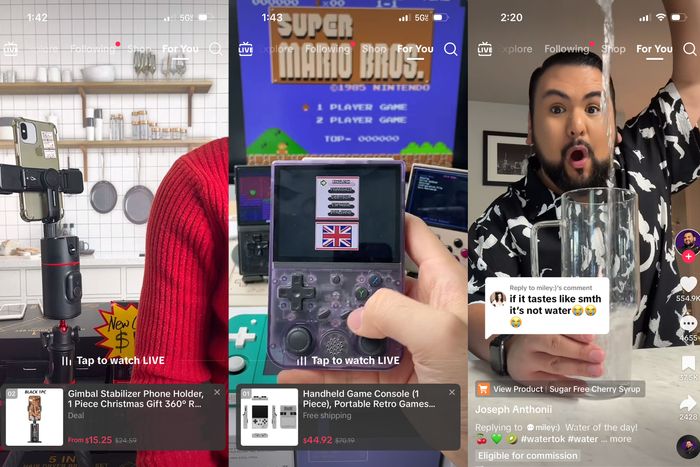

TikTok has always been an unapologetically consumerist space. The app’s algorithms are a good match for product recommendations, and its massive influencer economy brings with it a readymade sales and marketing infrastructure. In September, though, TikTok announced the “full launch” of the long-brewing TikTok Shop, which allows individuals and businesses to list and sell products directly in the app. At the same time, the company invited the rest of its users to promote sellers’ products — say, by including them in posts or livestreams — in exchange for an affiliate fee.

It’s a model that’s already working in other markets. TikTok’s cousin app in China, Douyin, was on track last year for sales exceeding $270 billion. This year, according to Bloomberg, TikTok is aiming for $17.5 billion in the U.S. alone.

You can tell: As far as such rollouts go — Instagram has been testing out shopping features for about as long as TikTok has been around — the launch of TikTok Shop was aggressive and complete. TikTok gave shopping features prime placement in the app, offered extremely steep discounts to sellers and buyers, and subsidized sales and shipping. Buying things is frictionless. Listing things for sale isn’t much harder.

Most significantly, as I found out, reaching potential customers is shockingly easy: In the course of testing TikTok’s seller tools, a placeholder listing for a used mechanical pencil got me more than a thousand livestream viewers, most of whom were as confused as I was. (More about that soon.)

Unlike its e-commerce competitors, Tiktok has a social network; unlike its social media competitors, parent company ByteDance isn’t afraid to jam e-commerce directly into its platform’s promotional machinery, for better or for worse. Maybe it’ll work. For now, it’s a fascinating mess.

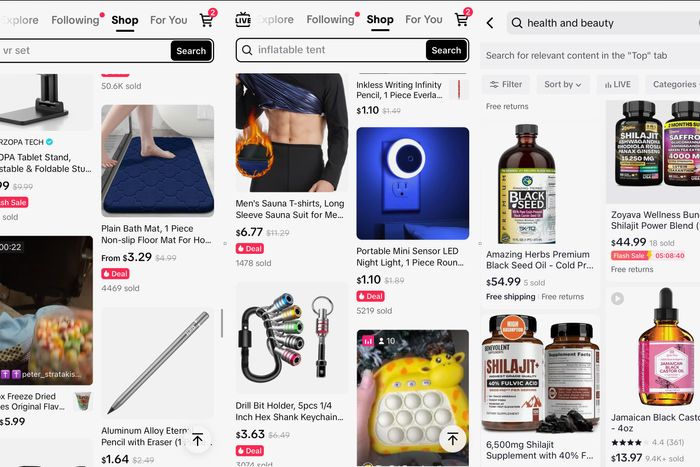

For TikTok users, TikTok’s transformation into an infinite dollar store has been hard to miss: ByteDance basically installed a Temu in the middle of the app, stocked with a mixture of a few influencer-adjacent TikTok brands and thousands of direct-from-China electronics, health and beauty products, household gadgets, garments, and food.

There is certainly some seller overlap — as on Temu, absurdly cheap Lenovo earbuds are everywhere. There are countless Stanley tumbler resellers and Stanley tumbler knockoffs. There’s a surprisingly wide-open marketplace for supplements, including vitamins sold directly by well-known brands and “cleanse” pills listed by sellers with no reputation at all. The main Shop page produces, for each user, a customized infinite scroll of recommended products — a demographic, personality, and behavioral profile rendered in thingies and doodads.

This resulting “mishmash of cheap knickknacks” (as a critical Bloomberg story describes it) isn’t necessarily a problem, at least in terms of its business prospects — the chaos grid is a standard shopping interface in most of the rest of the world and is quickly becoming one here, too. Likewise, the third-party marketplace model, with its rough edges and attendant questionable products, isn’t just shared with apps like Temu — it’s what substantially powers Amazon, which is increasingly playing in the same pool of cross-border sellers as its newer, China-based-or-connected competitors.

What makes TikTok Shop different — and potentially more consequential — is how the shop piggybacks on TikTok’s existing product, which is arguably the premier promotional platform on the American internet. ByteDance appears to be juicing e-commerce with everything it’s got. Where Instagram has spent years working up to (and eventually pulling back from) a similar goal, Tiktok has very quickly made major changes to its app in support of the Shop feature. As evident as this is to users, it’s even more evident to sellers, who, despite contending with new and sometimes glitchy infrastructure, including fulfillment systems, payments, and customer service tools, have an unobstructed view of TikTok’s potential as a conduit for stuff.

My first test of TikTok Shop was to buy something. I went with earbuds, a pair of JLab Jbuds Mini. These are available all over the place: Amazon, but also in-store at Target and Walmart. They retail for $40 but are often available at a modest discount; on TikTok, however, a combination of a first-time buyer coupon and a free shipping promotion meant that my total was just $17.99, delivered. They were sold by Jlabs, which operates a TikTok store, and which is likely to have made a small profit money on the transaction. TikTok, in contrast, will have taken a small commission on the sale but also spent at least $20 subsidizing it. According to TikTok’s own metrics, more than 32,000 of these headphones have been sold so far. Like Temu, in other words, this company is spending a lot to break into American e-commerce.

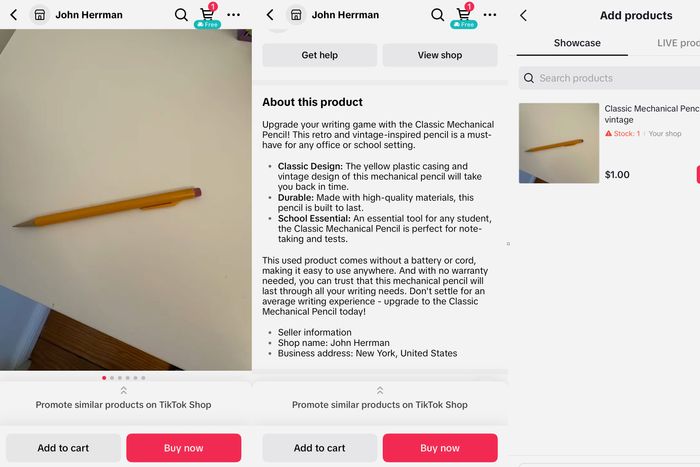

My next test was to list a product myself. I had no intention to sell anything, just to understand what sort of onboarding and vetting process TikTok had put in place, compared to its competitors. I registered as a seller using my TikTok account. After a brief identification and profile-building process, I was approved. I listed a product within arm’s reach at my desk, a gently used mechanical pencil, yellow, twist-type. I took a few photos, listed a few keywords, checked a few boxes, and let TikTok generate a product listing using AI. From “pencil, mechanical, yellow, classic, vintage” TikTok’s AI came up with a peppy intro — “Upgrade your writing game with the Classic Mechanical Pencil! This retro and vintage-inspired pencil is a must-have for any office or school setting!” — and made a bulleted list full of information, some of which I did not provide, and while not completely inaccurate, tended to, uh, assume the best about my product (“built to last,” “no battery or cord, making it easy to use anywhere”).

I submitted the listing and was rejected for a low-quality product image. Fair. I let TikTok “enhance” the lead image with more AI, which subtly altered the colors, and submitted it again. Success. After the product was live, I was prompted with a few possibilities. I could include my pencil in TikTok posts as a small tag. I could reach out to influencers to sell my pencil on commission. I could also go live, starting a stream in which to sell my pencil.

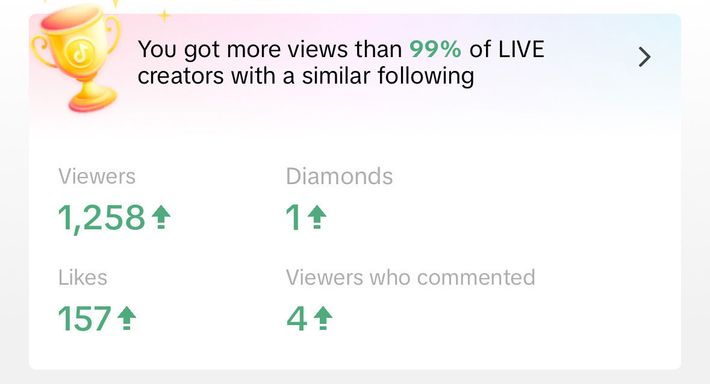

I decided to go live. The TikTok login I used for this experiment is a test account. It had, at the time, 34 followers — mostly random bots or botlike strangers, people I had interacted with in the process of reporting other stories, and a few friends who looked me up by phone number. The account had zero posts and very few interactions of any sort.

Still, when I went live, viewers showed up. I was expecting to poke around the interface for a while, and maybe ask a friend to take screenshots from the other side. Instead, within seconds, I was sitting in front of dozens of complete strangers who were waiting for me to talk. I ended the stream, adjusted my webcam, and started again. Within two minutes, I had hundreds of viewers. I asked them how they ended up there but nobody answered. I put on a face filter. I played carnival music. I showed them my dog. One informed me that the same pencil was much cheaper at the Dollar Tree. Another asked me if I had diabetes and then promptly left — much to think about.

I invited a friend to join the broadcast — another TikTok lurker who doesn’t post — and we chatted awkwardly for a few minutes. I talked up the pencil. I drew a face with the pencil. I shared that I was just working on a story, and apologized a lot. I was trapped in a tiny, live, and very stupid version of the defining TikTok creator experience, the source of the app’s intoxicating power: sudden virality with an invisible mechanism of action. If you want this, I’m sure it’s great. If you don’t, it makes you want to drop your smartphone into a barrel of wet concrete.

Multiple users added my pencil to their carts, but none bought it. Another friend I’d asked to join and monitor the stream ended up buying it for one dollar — the power of social commerce! — with the shipping cost subsidized by TikTok. The whole process, from opening TikTok to ending the stream, took a little over an hour. In the end, I made $0.69 cents, and TikTok lost at least $4. (The company recently announced it was normalizing some of its unusually low fees, and ending some early promotions). I printed a shipping label generated by TikTok and took the pencil to the post office. Since then, I’ve received daily emails about my product being “out of stock,” warning that, according to its estimates, I’ve been losing one dollar a day.

I had intended to broadcast to an audience of about three; in the end, my grueling stream for a worthless product reached more than 1,200 people and was “liked” by 157 of them. According to my account dashboard, this was an outlier experience, and my stream got more views than 99 percent of streams from accounts with similar (that is: basically no) followers — I strongly suspect that the reason the stream got an audience is that I was selling something — that I was using e-commerce features the company was trying really hard to promote, and that it rewards its users for trying.

According to the company, 89.7 percent of my viewers came from the “Inbox,” and 7.8 percent came from users’ main feeds, which suggests that thousands of people received a direct message notification that I, a person they do not know or follow, and to whom they have no other intentional connection, had gone live to sell a used mechanical pencil.

This is, in my case but also perhaps as a broader strategy, a massive waste of promotional firepower. Yet that promotional firepower, and ByteDance’s willingness to deploy it, is what distinguishes TikTok Shop from everything else. To be clear, the broader plan won’t work if the mixture of products remains questionable, or if TikTok can’t follow through on its plans to build a competitive domestic logistics infrastructure (my headphones were ordered a week ago and still haven’t shipped), or if it can’t keep people buying things without losing money on every transaction. It’s also easy to see how too much commerce could start to taint the broader experience of using TikTok. If adding an affiliate link to your every post is the best way for creators to make money, or if participating in the shopping economy is the best way to get viewership, then that’s what a lot of creators will do. They already are.

For ByteDance, though, that tradeoff could be worth it, and makes a sort of strategic sense. Ad sales are soft, big social-media platforms including TikTok are showing signs of stagnation, and e-commerce has plenty of room to grow. There are hairline cracks growing in Amazon’s business, and signs that Americans are, after years of ill-fated attempts by foreign companies, domestic start-ups, and tech giants, habituating to shopping routines that have been massively successful in China and elsewhere. Shein is reportedly making money, suggesting that direct-from-China e-commerce doesn’t have to be a money hole. TikTok’s more direct competitor, Temu, is further along but comparatively disadvantaged: The sort of advertising exposure its parent company has to pay for is precisely the product that TikTok manufactures by the person-century and already makes billions of dollars selling to others.

As with TikTok’s arrival as a social platform, its shopping venture — which is similarly disorienting, amateurish, and initially reads as downmarket — would be easy to dismiss as, basically, another conduit for junk, only this manifested in physical form. As it was last time around, this is a fair observation mixed with a questionable prediction: TikTok has done well for itself by pairing cheap, mass-produced amateur content with aggressive and metrics-driven machine-learning recommendations in an infinite feed. Why not actual stuff, too?

More From screen time

- Why YouTube Should Cut Off Its Thumbnails

- Luigi Mangione’s Full Story Isn’t Online

- Sam Altman’s Mixed Signals