Governor Andrew Cuomo asks the pilot to swing the state helicopter around so he can have a second look. About 1,000 feet below us, in a patch of Atlantic Ocean two miles south of Shinnecock, Long Island, a cargo ship equipped with a crane is lifting massive iron trusses and dropping them into the sea. The operation takes discarded material from one of the governor’s pet infrastructure projects — replacing the Tappan Zee Bridge — and uses it to expand two of his other initiatives, environmental protection and tourism, by creating an artificial reef.

As the helicopter tilts and turns to give Cuomo a prime overhead view, a campaign pitch starts to unfurl. “They’ve been talking about doing these things for so long, since when I was a kid,” he says. “And it was always, ‘Everything’s complicated.’ The Tappan Zee Bridge: ‘Wellll, the federal government, wellll, the local, wellll, the state …’ We’re actually doing it!”

Now the city is beneath us. Down there, things are messier for Cuomo: The subways are crumbling, and he’s being blamed. A federal trial is exposing the greasing of contracts for the governor’s signature upstate-redevelopment project. And a pesky primary challenger, Cynthia Nixon, is calling him a fake Democrat.

I ask Cuomo, if he’s so focused on action and results, whether he should have moved faster to overhaul the subway. Delays doubled between 2012 and 2017; the crisis escalated last year with derailments and chronic overcrowding. Cuomo argued that the city owned the subway and that Mayor Bill de Blasio needed to pay for half of the repairs. De Blasio pinned the blame on the Metropolitan Transit Authority, a state agency controlled, for all practical purposes, by Cuomo.

“The MTA — you have never seen a governor held accountable for the MTA the way the newspapers have tried to hold me accountable!” he shouts, only partly to be heard over the roar of the helicopter. “My father was governor for 12 years. Pataki. Never heard of a governor being held responsible for the MTA. And the law — the law! — is that the subway system is owned by the city! They own the assets, they own the stations, and they have total legal responsibility for all the capital money. Total. Legal. Responsibility. The truth is, it was this mayor’s lack of involvement — he retreated from Bloomberg and Giuliani! That was the void!” (“Well, that’s fundamentally untrue,” de Blasio tells me later. “And it’s strange to me that he’s much more comfortable praising Republicans than a progressive Democrat. And I think this is part of a pattern. He clearly is in charge of the subways.”)

Cuomo wants to spend a few minutes talking with his youngest daughter, Michaela, who is along for the ride today after finishing her sophomore year at Brown. We land, he hugs and kisses her good-bye, then invites me back to his midtown office. He has a whole lot more he wants to say.

Cuomo has in many ways been a highly effective governor. He deftly orchestrated the legalization of same-sex marriage. He stiffened gun laws. Reduced the cost of in-state college for some students. Revived segments of the moribund upstate economy. Launched a long list of major infrastructure projects. “Some folks thought that a $15 minimum wage was too ambitious. The governor got it done,” says George Gresham, the president of 1199 SEIU, the city’s largest labor union. Polls show that voters are likely to reward Cuomo in November by electing him to a third term.

What makes the governor fascinating is that his talents and achievements are so tightly bound up with his flaws. Cuomo has a genuinely compassionate, blue-collar side, and his work has improved the lives of thousands of regular New Yorkers, yet he is in a line of work that chews up the weak-willed. “People let the fact that he’s a son of a bitch interfere with the fact that he’s also been a very good governor,” a longtime colleague says.

And with that success he seems to grow crankier and more obsessed with the game. Some of Cuomo’s ferocity is both righteous and admirable — with the bonus of being politically beneficial — such as his vigorous support of post-hurricane Puerto Rico and his crusade against the NRA. And some of it has been part of his makeup for a long time, nurtured during his years managing the campaigns of his late father, Mario.

Now, after nearly eight years in office, Cuomo is an ever-more-distilled version of himself, driven to dominate the state’s political life and any would-be rivals. “The governor thinks he’s a hammer,” says a former Democratic adviser. “So everyone looks like a nail.” He has amassed a powerful conventional arsenal: labor-union endorsements; alliances with ethnic blocs; a $31 million campaign account, much of it raised from wealthy donors. And when he’s criticized, his first reaction — often deployed through surrogates or staffers — is to belittle or intimidate. “You’ve seen this play out with Cynthia Nixon,” a former aide says. “Instead of ignoring her, he followed the advice a political operative would give: Engage, undermine, outflank, try to co-opt, and then turn the heat on her. He gave her oxygen. The governor used to be more thoughtful about this.”

Cuomo’s insider, Establishment style has been potent locally, but it is increasingly out of sync with the polarized, grassroots Democratic moment. And it has given Nixon an opening, if not to defeat him in September’s primary, then to call him out on his compromises with state Republicans, including, in 2012, agreeing to gerrymandered legislative districts.

“He passed marriage equality, and he passed the New York safe act [restricting the sale of assault weapons],” Nixon says. “These are really the only two progressive issues that I see where he’s stuck his neck out and really led. If you look at his ‘free college for all,’ it’s free college for 3.5 percent of SUNY and CUNY students. His ‘pre-K for all’ — 79 percent of kids outside of New York City still don’t have it. It’s like George Bush announcing, ‘Mission accomplished.’ ” Cuomo parries that his free college program is just beginning and his upstate pre-K for all is being phased in.

Cuomo’s reaction to Nixon’s challenge has often been surprisingly clumsy: joking to a black audience that Jews can’t dance, walking into a gaffe while talking about women’s equality by declaring America “was never that great.” “The fleeting news cycle, the progressive left driving the energy and the conversation in the Democratic Party — the game has changed drastically during the time he’s been in office,” a New York Democratic strategist says.

“Yet he’s still playing from a 1990s playbook — the unions and the blacks and Israel and Puerto Rico. It feels like he’s a once-great athlete past his prime.”

Cuomo did recognize the larger trends even before Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez knocked off Joe Crowley, the House Democrats’ caucus chair, in Queens and the Bronx. And he has hustled to make his current campaign anti-Trump even more than it is anti-Nixon. How deftly he deals with the prevailing currents won’t simply decide his fate in New York this fall — it will determine whether Cuomo’s brand of hardball has a place in the 2020 Democratic presidential field.

Cuomo is standing in the middle of the Q-train tracks. There are no trains running on the line this sunny Wednesday morning in Brooklyn, though this shutdown is scheduled and a sign of progress: Workers are welding together 39-foot sections of steel track to eliminate the bumps that trigger false red lights in the subway’s insanely antiquated signal system.

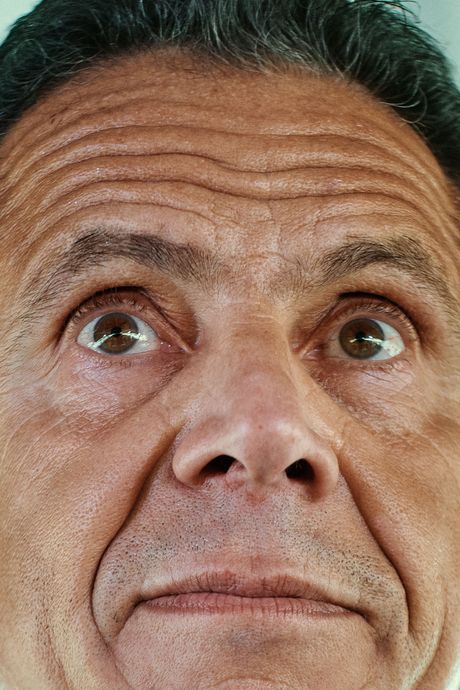

The work provides a flattering photo opportunity. This is Cuomo at his publicly happiest: the Action-Figure Governor. Wearing khakis and a white polo shirt with an oversize, customized governor’s-office emblem, his barrel chest puffed out, Cuomo is shaking hands with laborers (“Andy? That’s a good name!”), narrating the process (“These are the pieces of steel that are cut out so the tracks can be rewelded”), and then igniting a gunpowder-fueled three-foot column of fire that melts the metal to create a seamless bond.

Cuomo climbs a ladder onto the platform of the Avenue M station for a press conference. The governor’s record on the subway has been less than smooth: He’s been dinged for steering money from the MTA’s capital budget to pay for everything from debt service to countdown clocks. In 2016, he did push to complete the new Second Avenue line but at a cost of $5 billion to add three stations. And he supported installing Wi-Fi underground, which had the unintended side effect of allowing thousands of angry riders to tweet #FixTheSubway every time an F train stalled in a tunnel or a ceiling collapsed.

In June 2017, Cuomo declared a state of emergency and, one month later, implemented a Subway Action Plan, which sparked squabbling over who should pay. De Blasio largely won the public-relations battle to assign more responsibility to Cuomo, but the governor succeeded in getting the city to cough up $418 million toward his subway rescue plan. Cuomo declared victory, so today he is eager to show off the Q-track progress. He also can’t resist throwing yet another punch at de Blasio. “It’s the city that refused to fund,” he says. “And they refused to fund it for a year until, frankly, we did state legislation forcing them to pay for it.”

Cuomo may be America’s most frustrating major elected official: a Democrat with a genius for the dirty work of politics who sometimes loses sight of the big picture. “The governor’s greatness is in his tactics,” a longtime colleague says. “He’s always playing chess, and it’s never just about the next move. Yet lately he seems to have compromised the long game for shorter, more immediate wins, at times disregarding the broader implications and lasting effects of what he’s doing.”

Cuomo’s training as a sharp-elbowed operative started early, working on his father’s campaign in the 1977 brawl against Ed Koch for City Hall. He helped steer Mario Cuomo’s first three winning campaigns for governor. In 1994, Andrew was working as the Housing and Urban Development secretary in the Clinton administration when Mario ran for his fourth term, losing to George Pataki — a defeat that Andrew still blames on himself. After he left HUD, Cuomo tried to move from being a behind-the-scenes guy to becoming the face on the campaign brochure. It did not go well. Running against Carl McCall in the 2002 Democratic primary, he made several gaffes — including denigrating Governor Pataki’s actions after 9/11 — and dropped out before Election Day. Then his marriage, to Kerry Kennedy, crumbled. Both setbacks unfolded painfully and publicly.

Cuomo describes those years to me as “just a terrible period.” Mario, he says, was “like, depressed and out of politics. I’m, like, depressed that I came out of the governor’s race. We talk about what we could have done, what we should have done. He used to say, ‘We keep replaying the game. I shouldn’t have swung at that pitch, I should have swung at this pitch.’ And what we should have done if he ever got another chance. And then I get the second chance.”

Former aides say the McCall and Kennedy episodes were pivotal to what came next, and ever since, for Andrew Cuomo. When the second chance arrived, there would be no losing, no embarrassment. “The loss to McCall in particular was transformative,” one former top advisor, who has known Cuomo for 30 years, says. “After he was absolutely humiliated and brought to his knees by that experience, Andrew decided no one will ever have the power to do that to him again.”

Cuomo won the 2006 race for state attorney general; then, after Eliot Spitzer and David Paterson fell ingloriously by the wayside — with nudges from Cuomo, including investigations of how both his predecessors dealt with the state police — he was elected governor in 2010. Cuomo arrived promising to clean up corruption in Albany and make state government functional again. He made two deals in his first six months that were dramatic breakthroughs: delivering the state budget on time and legalizing same-sex marriage. One trade-off to achieve those goals, though, was a balancing act that propped up a Republican majority in the State Senate. In 2011, State Senate Republicans, who were just short of a numerical majority, and a splinter group of Democrats called the Independent Democratic Conference cut a power-sharing deal; Cuomo played along with the arrangement. The maneuvers paid short-run benefits to the governor: He distanced himself from a set of soon-to-be-indicted Democratic leaders, and the State Legislature didn’t move policy to the left any faster than he thought wise or in a way that might hurt him with more conservative upstate voters. It was a tactical move that would cement the governor’s reputation among some liberals as a man without principles.

Clashes with de Blasio, who ran as an avowed progressive crusader, haven’t helped that reputation. Twenty years ago, the two men were genuine friends, with Cuomo hiring de Blasio to work at HUD and de Blasio standing by Cuomo during his bumpy exit from the 2002 gubernatorial race. That past kinship may be part of the problem. Cuomo, former associates believe, thinks de Blasio didn’t give him enough credit for his role in the mayor’s political rise. To me, Cuomo insists his differences with de Blasio are entirely professional, not personal.

What really doomed the relationship, in the view of Cuomo’s camp, was the newly elected de Blasio’s pressing his case, in 2014, for raising tax rates on the state’s wealthiest residents, a so-called millionaire’s tax, to pay for universal prekindergarten. “It drove the governor crazy,” a former top adviser to Cuomo says, explaining that Cuomo found de Blasio to be both disobedient and wedded to empty rhetorical gestures. “He told the mayor, ‘We’re going to give you pre-K. It may take a while. We may have to bang you around a little bit. But you’re getting pre-K. Now, understand my politics, Bill. I just fought off this millionaire’s tax. I need the business community right now because I’ve got to get an on-time budget. So don’t come up to Albany and reopen that issue.’ Bill de Blasio comes up to Albany.” The governor and mayor exchanged potshots, with de Blasio’s side arguing it needed to maintain pressure to guarantee the pre-K funding, which Cuomo did eventually deliver.

Months later, the mayor energetically campaigned to try to elect a Democratic majority in the State Senate. Cuomo was in favor of that too — though his conception of how to get there was decidedly different. In de Blasio’s view, this was the moment things went permanently south. “I was struck by his unwillingness to tax the wealthy, and I felt he was not willing to challenge some powerful interests in this state. And it was a source of tension,” de Blasio says of the pre-K battle. “But I don’t think that was the most essential problem. I think the break between us revolves around the promise he made to help us win a Democratic State Senate and the fact that he broke that promise. It’s now quite clear that over the years, he aided and abetted the IDC and the Republicans, and that to me was a real breaking point.”

Cuomo has always maintained he did everything he could to win a State Senate majority in 2014 and that he had nothing to do with the creation or functioning of the IDC. De Blasio grew exasperated, though, going on NY1 in 2015 and accusing Cuomo of waging a “vendetta” against anyone who dared disagree with him. “With all due respect, maybe what the mayor was witnessing is something different,” a former Cuomo adviser says. “Which is ‘We hate you until we need you, and then we love you.’ Which is not hard to understand, and right then, we were in the ‘We hate you’ phase. But there will come a point in time when we need you, and then we’ll love you.”

The hatred phase, however, seems to have become permanent. This spring, federal prosecutors were investigating the city’s falsification of lead-paint-removal efforts in public-housing projects. Cuomo used it as an opportunity to make multiple media-friendly appearances in NYCHA buildings, highlighting the grim conditions and volunteering state money to speed repairs — but only if a new state monitor controlled the contracts. The public shaming seemed as much about rubbing de Blasio’s nose in the mess as it was about helping people who live in shabby public-housing complexes. “Andrew is vindictive,” a Democratic strategist says. “He wants to punish people. And he gets joy out of that.”

The governor, however, strenuously disputes that notion. “There is no ‘they’ who really knows me, who is out there talking to anybody. It’s all baloney,” Cuomo says. “I’ve worked very hard at getting to a place in life where I just let it alone. I just give it up. Just release past transgressions, conflicts. It’s just not worth it. People are complicated little things, and life is too short. I don’t think I have any ongoing anything with anybody right now.” Well, other than de Blasio. When I ask if maybe he would be better off not punching at the mayor, Cuomo snaps forward in his chair. “He started with me first!”

Their fight over the MTA is in some ways just getting going. Cuomo has lately become a lukewarm advocate for congestion pricing as a way to raise the billions in repair money requested by new MTA president Andy Byford. But the governor says he expects a repeat of this year’s battle with de Blasio over who should pay. The mayor has returned to the idea of a millionaire’s tax to cover the expenses. Cuomo shakes his head. “He knows the millionaire’s tax is going nowhere in the Legislature,” the governor says.

“I think that’s more of a statement of his unwillingness to tax millionaires than it is of political reality,” de Blasio responds. “He should be providing leadership in demanding that the wealthy pay their fair share.”

It’s true that State Senate Republicans (and some Democrats) have fought off tax increases. Yet control is likely to shift this November — ten seats are up for grabs, and flipping one seat from red to blue would change the balance of power. Many of the Democratic primary contenders are insurgents who say Cuomo’s dealings with the IDC motivated them to run. A new Democratic majority could put the governor in the uncomfortable position of deciding whether to sign a bill raising taxes. “We have a millionaire’s tax, and it is the second highest on the eastern seaboard,” Cuomo tells me. “A very small number of taxpayers pay the predominance of our taxes. They are very rich, and they are very mobile. Second, you just had Trump and the Republicans end the deductibility of state and local taxes, which means everybody pays 30 percent more. At what point do people leave and it actually costs you revenue?”

The beer and wine is flowing freely, and it is being consumed by the craft brewers and vintners who make it. Six years ago, Cuomo spotted a retail and tourism opportunity and successfully backed the industry by cutting regulations, adding tax credits, and regularly talking up the state’s booze business. So this is a happy bunch, genuinely grateful for the governor’s support. But it’s a wised-up group, too, so tonight 200 small-business operators from across the state have paid $50 to $25,000 a head to gather in an airy loft on lower Fifth Avenue and toast their political patron. Cuomo is charming and relaxed; he even sips a small amount of the Ithaca Beer Co.’s product.

Most of Cuomo’s cash comes from donors with more expensive tastes than this crowd. Cuomo rakes in money from corporate, hedge fund, and real estate interests. “Why raise $31 million — and, by the way, at a real cost in terms of time and energy, and at a political cost because it makes you king of the LLC?” a Cuomo insider asks, referring to a loophole through which corporations can pad their political contributions. “The governor is acutely aware that it’s not just about the dollars to spend. It’s the perception. ‘You want to run against me? You better be prepared.’ And it says to the world, ‘I have access to really deep pockets.’ How much traction is Cynthia Nixon getting by saying she won’t raise from LLCs? You can tweet about it all you want, but — he’s got $31 million.” Even before Trump taunted Cuomo in a speech last week, the governor was deeply concerned that Trump would direct rich cronies to fund his possible Republican general election opponent, Marc Molinaro.

Cuomo’s cold-blooded realism and competitiveness are inherited. The hallway to his Third Avenue office in midtown Manhattan is lined with photographs of his father. He stops and stares at a shot of the two of them playing basketball. “You see him pushing me?” Cuomo says with a laugh. The governor, who will turn 61 in December, seems to be feeling the passing of time more acutely. “Nobody has wisdom and history,” he says. “When do I miss my father most? Every day.”

Cuomo has fresher extended-family disappointments to brood about. For years, Joe Percoco acted as Cuomo’s political enforcer, as well as his eyes and ears, recognizing problems before they turned into headaches and brokering compromises. Percoco played a pivotal role in the 2011 Marriage Equality Act, persuading leaders of the state’s Orthodox Jewish community not to fight the proposal. Percoco was more than a top aide, though: At Mario’s funeral, Andrew described him as his father’s “third son.” In March, Percoco was found guilty of three felonies for soliciting and accepting $300,000 in bribes from the executives of two companies doing business with the state during a brief period when he was off the state payroll.

“Joe was the alter ego and the filter,” a prominent state Democrat says. “He would speak with the strength of the governor behind him, because it was true. And he also created a layer of protection. The governor wasn’t getting his hands dirty by Joe doing all that stuff.”

A second scandal came to an ignominious end in July. Cuomo, through his “Buffalo Billion” project, has poured redevelopment money into the state’s second-largest city. One element was a massive factory to produce solar panels. The governor’s point man on the project, Alain Kaloyeros, was convicted of rigging construction bids so the winners were two firms that happened to have given tens of thousands of dollars to Cuomo’s campaign.

Cuomo argues that the Buffalo and Percoco cases are the deeds of isolated bad actors. Kaloyeros, he says, had a sterling track record, had worked for multiple prior New York governors, and was under the supervision of SUNY administrators. “Percoco did really stupid things. Hurtful and disgusting and stupid, but stupid. And I had absolutely nothing to do with anything,” he says. “So in Cuomo’s administration there was a guy who was dirty? Yes. Well, that’s terrible. And I’m going to condemn him for it. If I’m you, and I’m smart, I say, Preet Bharara” — then the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York — “doesn’t go after Percoco to go after Percoco.

He’s going after Percoco to get the governor. That means they had to go through every piece of paper and every email for two years. And that they couldn’t find any connection whatsoever, in many ways it’s the most credible exoneration in history, because Preet was a scalp hunter and that’s all he was. If he had Joe Percoco and every file from Joe Percoco and he can’t find a whisper on me, that is a hell of a thing.”

Bharara, during eight years as the U.S. attorney, won about a dozen corruption convictions of state politicians, including the leaders of both houses of the State Legislature. “I appreciate Andrew Cuomo’s need to spin,” Bharara tells me. “But I don’t think he has anything to be proud of in the Buffalo Billion scandals or, frankly, in his record on corruption generally.”

Cuomo’s relationship with another prosecutor, State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, was also chilly, though in recent years the two had settled into a wary truce. In late April — roughly two weeks before The New Yorker broke the story — word reached Cuomo that Schneiderman was on the verge of some serious trouble. “I thought it was going to be survivable,” Cuomo says. “I thought it was going to be ugly, but I didn’t have any idea that it was going to be that bad.” After the story broke alleging that Schneiderman had physically abused multiple women, Cuomo quickly issued his own demand that Schneiderman resign, then got to work sizing up possible successors.

Letitia James, the current New York City public advocate, had been an assistant attorney general under Eliot Spitzer. That James is an African-American woman from the party’s progressive wing who has strong appeal in voter-rich central Brooklyn also made her a welcome addition to Cuomo’s ticket this fall.

James’s liberal political roots presented a complication, though. The Working Families Party had been crucial to James’s electoral career, but the WFP was now in a bitter battle with Cuomo, and the party had already endorsed Nixon for governor. “I tried to work with the guy for eight years, because we’re the WFP — we’re not the Green Party. We’re trying to actually get stuff done,” says Bill Lipton, the WFP’s executive director. “The truth is Cuomo has no policy or values base at all. What he cares about is keeping taxes low on his donors. That is why I am motivated to run against him, even if it destroys our organization. If I have to get a new job in a year, I don’t care. We’re going to hold this guy accountable.”

So James faced a stark choice. “Her problem, if she wants to be AG, is that the governor could stand up other candidates against her,” a former Cuomo colleague says. “So how do you get it locked? Make sure the governor is behind you. So you’ve got to be smart and walk away from the WFP, because the governor is in this death match with them.” James declined to pursue the WFP’s ballot line in the primary; both she and the governor say Cuomo had nothing to do with her decision. In late May, James became the Democratic Party’s official “designee” for attorney general.

Cuomo, despite all his strengths, at first appeared spooked by the challenge from Nixon. One day after the neophyte candidate announced she was running, one of Cuomo’s allies, the former City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, unloaded on Nixon as an “unqualified lesbian.” Cuomo himself has hastened to take liberal-friendly positions on everything from brokering the dissolution of the IDC to restoring voting rights for paroled felons to banning plastic bags — things he might well have rolled out to boost his Democratic-primary stock no matter who the opponent, but that looked panicky coming on the heels of Nixon’s announcement.

Does Cuomo think Nixon is qualified to be governor? “That’s for the people to decide,” he says slowly. “I’m voting for me.” Does he consider her an elitist? “That’s not — that’s not for me to comment. I think there’s enough negativity.”

Cuomo’s brand of carrot-and-stick triangulation, learned in part during his years working under President Bill Clinton, hasn’t sold well in the national Democratic Party since, well, Bill Clinton. Cuomo, though, believes Trump is making results-oriented pragmatism relevant again. “Is there a lane for a person who has governed a complex state and actually accomplished more left positions than any other state?” he asks. “I would hope so, otherwise the Democratic Party has lost touch with reality.”

Even though liberal voters, in the wake of Bernie Sanders’s 2016 run, will likely be a greater force? “Mario was never liberal enough, Koch was never liberal enough — Obama wasn’t liberal enough! ‘Shoulda been single payer, he’s a sellout,’ ” Cuomo says sarcastically. “There is an institutional far left who’s always contrary-left. You’re going to have to beat [Trump] with an authentic, reality-based alternative who says, ‘We can do this.’ I don’t have to be the candidate, but somebody needs the playbook and is going to say, ‘I’m going to do what they did in California on renewable energy — it works, it’s been in place five years, nothing bad happened, the world didn’t collapse.

I’m going to do free college like they did in New York City.’ ”

Cuomo doesn’t need to be the candidate — but he could be the candidate. “I don’t have plans to do that,” he says. “I’m running for governor, and I have no plans to run for anything else.” Assuming he dispatches Nixon in September and Molinaro in November, Cuomo has an impressive agenda lined up for his third term — major renovations of JFK, La Guardia, and a half-dozen upstate airports, plus overhauls of the Long Island Rail Road, the city subway system, and the upstate economy.

The interview has run long. I am halfway out the door, but Cuomo starts repeating his argument about how the city, not the state, has historically been responsible for the subway. “I seem to remember a governor building the Second Avenue line,” I say. “Yeah!” Cuomo says brightly, launching into a story about how, when contractors wanted to push back the deadline, he intervened, threatened to bar them from ever doing business with the state again, and floated the possibility of a Securities and Exchange Commission investigation. The job got done, and the story makes him grin wider than he has all afternoon. Andrew Cuomo is many things. But relentless remains at the top of the list.

*This article appears in the August 20, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!