This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Joel Wertheimer took a job in Andrew Cuomo’s administration in February 2017, straight from his position in Barack Obama’s White House. He came on alongside almost 30 other new hires, many of whom had also worked for the outgoing president or on Hillary Clinton’s campaign and were seeking a progressive professional path through the Trump years. Some saw New York State government as a bulwark against what they feared Trumpism would bring. Others hoped it could be a laboratory for ideas that might become a model for federal policy.

Early in their employment, a few of these staffers were invited to a party at the governor’s mansion in Albany. Partway through the bash, there was a roast of Cuomo’s top aide, Melissa DeRosa, then the chief of staff but soon to be promoted to secretary to the governor. The roast, said Wertheimer, entailed projecting photos of prominent state officials, “then asking Melissa if she knew their names, and her not knowing.” The newcomers whispered and huddled together while everyone else laughed. “We were saying to each other, ‘This is fucking weird,’ ” said one former staffer. “This was not ha-ha funny,” Wertheimer explained. “This was, ‘You guys are bad at your job!’ And, ‘You’re mean!’ ”

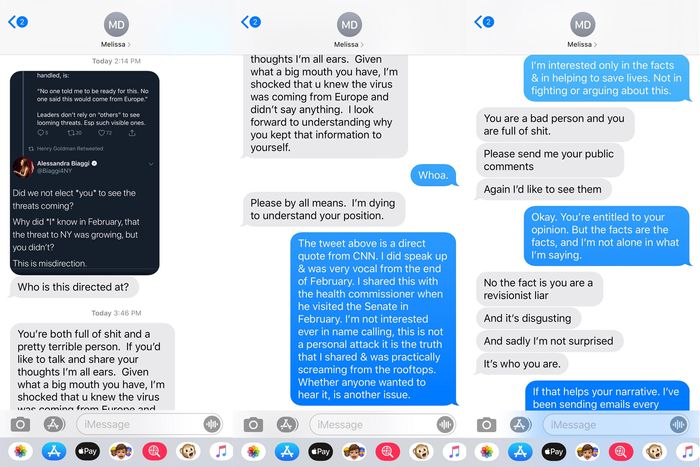

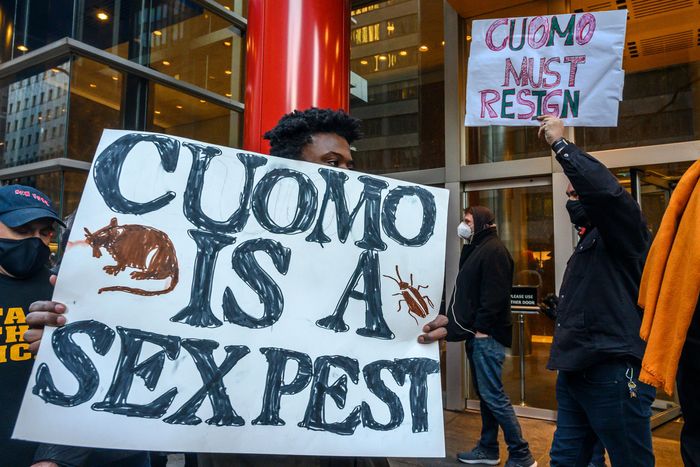

Four years later, and one year after he began his star turn as “America’s Governor,” steering his state through COVID via daily, reassuringly matter-of-fact press briefings, Andrew Cuomo’s third term as governor of New York is suddenly deeply imperiled. In January, State Attorney General Letitia James released a report showing that his administration had underreported COVID deaths in nursing homes by as much as 50 percent. In February, liberal State Assembly member Ron Kim, who had criticized the governor in the wake of that report, spoke publicly about how Cuomo called him at home and threatened his career. Then the floodgates opened: His adversary Mayor Bill de Blasio called the bullying “classic Andrew Cuomo”; state legislators Alessandra Biaggi and Yuh-Line Niou began openly suggesting that the governor’s hard-knuckled approach to politics is simply abusive. And since last month, when Cuomo’s former aide and candidate for Manhattan borough president, Lindsey Boylan, published an article on Medium accusing him of sexually harassing and kissing her against her will, five more women have come forward with tales of harassment, objectification, and inappropriate touching. As of publication, dozens of Democratic members of the State Assembly and Senate, and 11 Democratic members of Congress, have called for his resignation.

That Andrew Cuomo is being characterized by fellow Democratic politicians as a lecherous tyrant who empowers his staff to threaten and intimidate should not, in some ways, come as a surprise. During his decade as governor, he has often strutted his thuggish paternalism while his top aides disparaged those who challenged him. Two years ago, a Cuomo spokesman called three female state lawmakers in his party “fucking idiots.” In 2013, Cuomo created the Moreland Commission to investigate public corruption, only to shut it down abruptly less than a year later amid allegations that he had obstructed its work; one of Cuomo’s closest associates, Joe Percoco, is serving a six-year term in federal prison on bribery charges.

But until now, none of this left a lasting mark on the governor. If anything, it burnished his reputation: Cuomo was a bully, but he was our bully. Over the course of the past year, however, as he took his show national as Governor Covid, the political dynamics in Cuomo’s own state were shifting. Now, the venal toxicity that has buttressed his career has, at least temporarily, been exposed for what it is.

Though the multiple scandals erupting in Albany seem to toggle between sexualized harassment stories and evidence of mismanagement, what is emerging is in fact a single story: That through years of ruthless tactics, deployed both within his office and against anyone he perceived as an adversary, critic, or competitor for authority, Cuomo has fostered a culture that supported harassment, cruelty, and deception. And while some have continued to defend Cuomo’s commitment to “creating the perception of strength,” and his mastery of “brutalist political theater” (as Mayor de Blasio’s former spokesman told the New York Times last month), his tough-guy routine has in fact worked to obscure governing failures; it is precisely what has permitted Cuomo and his administration to spend a decade being, to borrow Wertheimer’s assessment, both mean and bad at their jobs. As one former Cuomo staffer told me, “The same attitude that emboldens you to target a 25-year-old also emboldens you to scrub a nursing-home report.”

Cuomo’s leadership style often confuses ruthlessness with greatness, abuse with strength. Interviews with dozens of former Cuomo employees and those who have worked with or adjacent to his administration reveal a governing institution that has been run, at times, like a cultish fraternity, and at others, like a high-school clique — a state executive chamber in which the maintenance of power, performance of pecking orders, and pursuit of competitive resentments matter as much as policy. As Wertheimer said of many of those who entered the Cuomo administration alongside him: “People came in, looked around, and did the Grampa Simpson meme; we just turned back around and left.” Wertheimer quit seven months after he started. “It’s this total toxic masculine bullshit that disguises a very poorly run place.”

In 2016, Kaitlin, who asked that her last name not be published, was working 9-to-5 for a Democratic congressman and waiting tables nights and weekends in order to make rent and pay down student loans. In the fall, she was offered a job at a lobbying firm that paid her enough to cut back on waitressing to just weekends.

Six weeks after starting her new job, Kaitlin was working at a fund-raiser that her firm was hosting for Cuomo. As the governor left, he stopped to greet staffers of the event; when he approached Kaitlin, she introduced herself and told him that she used to work for a politician. To her surprise and confusion, he replied that she would soon be back in government, this time at the state level. “Then he grabbed me in a kind of dance pose,” she said, while a photographer snapped a picture. “I was thinking, This is the weirdest interaction I’ve ever had in my life … I was like, Don’t touch me. Everybody was watching.” Kaitlin recalled feeling uncomfortable and embarrassed in front of her new colleagues — “my whole team of people I’d just met” — who gathered around her after Cuomo walked away, joking “Oh, the governor likes you.”

That same week, Kaitlin received a voice-mail from Cuomo’s office asking her to interview for a job. She had not provided his representatives with contact information; they had found her on their own. She disclosed this to her new bosses, who understood her discomfort but explained that he was the governor and that she would have to take the meeting. When Kaitlin turned to several of her former supervisors and mentors for advice, they repeated the same, explaining that, professionally, she had no choice but to go to the interview and take the job he offered her.

“We all knew that this was only because of what I looked like,” said Kaitlin. “Why else would you ask someone to come in two days after you had a two-minute interaction at a party?”

Once she started, Kaitlin said, there wasn’t much direction about what she was supposed to do, except to “be a sponge,” learn from senior women in the office, and react to the governor’s capricious moods. Some mornings, Kaitlin would hear her BlackBerry ping with the message that Cuomo had left his Mount Kisco home earlier than scheduled; she would have to rush out of the shower to sprint — with wet hair, in heels — across town to be at the Manhattan office, at 633 Third Avenue, when he arrived. On those mornings, he would comment on why she didn’t look put together. “ ‘You decided not to get ready today?’ Or, ‘You didn’t put makeup on today?’ ”

In speaking with 30 women about their experiences with Cuomo, almost all who worked for him commented on the extreme pressure applied by both the governor and his top female aides to dress well and expensively; some were told explicitly by senior staff that they had to wear heels whenever he was around. Kaitlin was still paying off her student loans. “I did what I could with my clothes,” she said, “and it wasn’t good enough for them. I didn’t have designer stuff.” She remembered wearing a red plaid Gap button-down shirt she’d thought was cute, but the governor remarked that she looked “like a lumberjack.” (According to a Cuomo spokesperson, “There is not now, nor has there ever been, an expectation to wear certain clothing or high heels.”)

The governor never touched Kaitlin inappropriately or made any explicit sexual overtures, she said, but his reactions would sometimes make her feel self-conscious, such as when she asked him if he wanted her personal cell-phone number: “I thought that was a normal thing to offer your boss,” she said, but he behaved as if she’d come on to him. Like other women who have come forward, she remembered him asking questions about her dating life. Once, in Albany, he brought her in to show her a room adjacent to his office; it was cold, and he was standing very close to her in a way that made her feel so profoundly uncomfortable that she remembers shaking.

On a different day, in Manhattan, Cuomo asked her to come into his office and look up car parts on eBay. “He sat at his desk and angled his chair around.” It was a tight space, with Kaitlin standing between the seated governor and the computer he was asking her to work on. “So I was standing there, in a skirt and heels, having to bend over his computer, with him looking at me, and me looking up car parts.” (In response, Cuomo’s spokesperson noted: “The governor is notoriously technologically inept — male and female staffers have for years assisted the governor with his computer.”)

Not long after she started, she said, Cuomo’s people rented out Dorrian’s for a Super Bowl party. At the end of the night, after the bar opened to the public, Cuomo was sitting in the back room talking to a young woman with a dove tattooed on her hand. At a staff meeting the next morning, Kaitlin said, Cuomo asked his aides to find the woman with the dove tattoo and to consider offering her a job. Kaitlin described the uncanny realization that this was likely how it had gone the morning after she’d met him.

After every public event, Kaitlin sorted through photographs of Cuomo posing with guests, selecting images to which he would append personal notes. She said he always paid special attention to pictures of himself with pretty women. If he didn’t like how he looked in them, he would yell at Kaitlin. “I got screamed at for a lot of bad photos,” she told me.

Kaitlin described a culture in which dishonest power plays were frequent. The phones at the office had push-tone keys that would stick, and sometimes she’d lose a call as she transferred it. She recalled that Cuomo once said, “You can’t figure out the fucking phones — I’m going to end your career.” Miserable, Kaitlin began to consider how she might get out. It was widely rumored the Cuomo administration would impede one’s efforts to find a new job and could get an offer rescinded. “I can’t tell anybody,” Kaitlin says she thought at that time. “But I couldn’t keep doing what I was doing. I’d cry all the time. I thought I didn’t know how to do anything anymore — not even basic life skills.”

Kaitlin did not know whether her experience with Cuomo met the legal definition of sexual harassment, though she did feel that she had been “verbally and mentally abused by him and his staff” and said that she has described the work style — to friends and a therapist — “as a form of coercive control.” When she finally interviewed for a job at the state authority where she now works, she cried.

Over the past few weeks, there has been a slow drip of reporting on Cuomo’s allegedly inappropriate behavior toward women: 25-year-old Charlotte Bennett told the Times that this summer, when she was working for him, he made invasive comments about her experience of sexual assault and suggestively asked whether she would date older men; Anna Ruch recalled him touching her back, grabbing her cheeks and asking if he could kiss her at a wedding; a recently resurfaced video shows Cuomo summoning a television reporter to his table at the 2016 New York State Fair and urging her to “eat the whole sausage,” joking as she takes a selfie of them with a sandwich, “There’s too much sausage in that picture”; most recently, an unnamed Albany staffer has lodged a complaint that the governor put his hand up her shirt after she was called to the governor’s mansion to help him with an IT problem (that complaint has now been referred to the Albany police).

The stream of stories has been both upsetting and disorienting. Some of the reports are clear cut. Others have attempted to force stories of discrimination and misconduct into the rubric of sexual harassment via a blunt tallying of violations that are graded on a scale: a kiss on lips or cheeks; an inappropriate touch at work or at a wedding; a hand on a shoulder or the small of a back. More than three years after the reporting on Harvey Weinstein’s violent predation and the reckoning it provoked, we have been conditioned to draw bright lines around certain inarguably bad actions. This has led to a revolutionary shift in workplace culture, ending the careers of many powerful people who had abused women (and men) with impunity, while fundamentally changing our language and understanding of professional misconduct. Still, the very extremity of bad behavior exposed in the wake of Weinstein has, ironically, limited the conversation around workplace harassment. We are sometimes too quick to apply flat metrics to judge isolated incidents, and thereby miss the opportunity to fully assess and address the harm, inequity, and discrimination that happens on a subtler, but no less pervasive, scale.

Cuomo’s treatment of some of the young women who worked for and around him demonstrated a kind of diminishment and tokenization that may take a sexualized form, and may involve objectification and flirtation, but which didn’t always entail explicitly sexualized contact or connection. In fact, Cuomo may be a textbook example of how sexual harassment, like sexual assault, isn’t about sex at all; it’s about power. In Cuomo’s case, it was one manifestation of his obsession with performing dominance, emphasizing the gulf of authority between the governor and those around him, making himself feel big and conveying to others that they were small.

Ana Liss, 35, who told The Wall Street Journal of her experiences of feeling devalued by Cuomo, entered his administration fresh from her beloved hometown of Rochester in 2013, full of “Pollyanna thinking,” she said, about how to make her state a better place. On one of her first days on the job, she told me, Cuomo approached her and asked, “Do you have a boyfriend?”

He came up with nicknames for her — “Sparky,” “Blondie,” “Sweetheart,” and “Honey” — and, she said, “he was just flirtatious.” (Boylan has also claimed the governor called her by the name of a rumored ex-girlfriend he said she resembled; Kaitlin said he called her “Sponge.”) Liss remembered an executive assistant in Cuomo’s office, someone who had worked in the capital for decades, once telling her, “He thinks you’re cute; the governor likes you.”

She did find it odd, she said, that “there was nobody that was unattractive. I felt like I was in Stepford Wives but with younger women. His briefers were always beautiful, leggy young women right out of college.” The same executive assistant advised her, she said, that “when the governor is here, you need to look really good.”

During her two-year tenure, Liss was asked to participate in certain special events: a Father’s Day party the year Mario Cuomo died and a “pinning ceremony” at the governor’s mansion. She was given a state trooper’s card and a badge that said EXECUTIVE CHAMBER. She tried to tell herself these trinkets and invitations were merit-based. But, Liss said, “I did know in my heart of hearts that it’s because the governor thinks I’m cute.” At parties, when Cuomo would put his hand on her back, she was always torn, she said: “On the one hand, I was like, Wow, look at me; then I felt gross about it. I didn’t know if he actually even knew my name. He just thought I looked good in that dress.”

At the time, Liss didn’t think of these experiences as sexual harassment. She still values her mementos: the pin, the badge, the card, and a duffel bag from that Father’s Day party emblazoned with the words CUOMO 52 AND 56. But the governor’s coy remarks during their time working together often left her unsure of what to do or say. “When he looked at you — you know that scene in Jurassic Park when the Tyrannosaurus rex peeks into the car? It was like that.”

Liss became depressed, lost weight. “I felt gross, like I was just an ornament.” She said that she had “never felt more depleted by the male gaze” than the time she spent in Albany. “Melissa DeRosa had Louboutins, and there were legs everywhere, and I just felt stupid. I was living in a place that was full of people who were mean and predatory. It ground me down to the lowest point of my life, like I was a piece of nothing and my career was going nowhere.”

Brute white patriarchy has been a political norm since the beginning of American politics. New York City, New York State, and the United States of America share rich histories of installing hot-tempered white men in positions of political power and too often seeking comfort in them in moments of crisis or fear. I remember liberal peers talking about the sudden affection they felt for our deranged, fascist then-mayor in the wake of 9/11; I thought a lot about that last spring, when many were describing themselves as “Cuomosexuals.”

Cuomo is an American patriarch connected to a long line of American patriarchs: He is the son of a three-term governor, brother of a CNN anchor; he was married to and had three children with Kerry Kennedy, the daughter of the late New York senator and U.S. attorney general Robert Kennedy, niece of President John Kennedy and Senator Ted Kennedy. He later had a long partnership with Sandra Lee, whose “Semi-Homemade” brand began with a deal at Miramax in 2002; in 2016, Lee described Harvey Weinstein as “the original ‘Magic Man’ ” and “a catalyst to my career.”

Though Cuomo hasn’t been accused of anything like the violent crimes that Weinstein committed, he shares other traits with the now-imprisoned movie producer. For years, Weinstein’s famously bad temper and difficult workplace demeanor were understood simply as quirky symptoms of his genius, somehow permissible because everyone knew about them and no one did anything about them; it was just “Harvey being Harvey.” Cuomo’s behavior has also long been excused as Andrew being Andrew; just a powerful man being powerful. Like Weinstein, Cuomo regularly has people yell for him, including a phalanx of senior women whom he uses as a defensive feminist shield, making sure to note in his first news conference after the allegations that “we have more senior women in this administration than probably any administration in history.”

But like the women Harvey empowered at his movie companies, many high up in Cuomo’s employ repeat and amplify the kinds of abuses that begin with the boss. Most people I spoke to about their relationships with the governor have memories of being yelled at, threatened, or insulted by senior female colleagues, especially Melissa DeRosa.

Powerful white women have often benefited from, and thus worked to uphold, abusive patriarchal power systems. DeRosa might be a perfect specimen. She is, those who have worked for and alongside her say, the person who has most absorbed from the governor his talent for ferocity and is eerily skilled at conveying his presence and asserting dominance over whomever she’s dealing with.

Like her boss, she often does this under the guise of girl power. Both Cuomo and DeRosa, who heads New York’s Council on Women and Girls, regularly wield feminist language as a cudgel against feminist critics. On March 8, DeRosa took to Twitter to tout Cuomo’s high approval ratings with women as defense against allegations of harassment. And at the briefing when Cuomo first addressed harassment claims, DeRosa was at his side, spouting a word cloud of pseudo-feminist obfuscation about the administration’s work to “further women’s rights, to expand protections for women in the workplace, maternal health, reproductive health” (claims complicated by the administration’s cuts to Medicaid eligibility and long delays in pushing through the Reproductive Health Act). She touted the number of women appointed to senior staff, claiming that “we’ve promoted each other and we’ve supported one another.”

But many women who worked with DeRosa recalled her as the opposite of supportive, describing her instead as territorial and unkind. When Kaitlin arrived at Cuomo’s offices, she said, the senior women “didn’t like that the governor liked me” and that Cuomo seemed to take pleasure in this. “He would ask, ‘How are the mean girls?’ ” she said. One male staff member told me, “If you weren’t in the Melissa, Jill, and Stephanie crew, you didn’t really exist.” Another woman described an instance in the ladies’ room, “when Melissa looked at me; I could not have felt like less of a human being.”

In March 2019, Camille Rivera, former political director of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, who had a cordial — if delicate — relationship with the administration, was growing irritated by what she viewed as Cuomo adviser Rich Azzopardi’s habit of publicly directing vitriol toward women. When she saw him belittling Andrea Stewart-Cousins on Twitter, she lost patience and replied, “ ‘This is what happens with men of white privilege; someone else would have been called out for attacking the majority leader of the Senate, who is a Black woman.’ ”

It was not long before she heard from DeRosa, screaming at her to take her tweet down. The fight got so intense, Rivera said, that DeRosa was yelling, “ ‘What are you going to do about it?’ and I was like, ‘You’re the one with the black Suburban; you come over here and tell me what you’re going to do about it.’ ” In the midst of their argument, Rivera got a call from her boss, who was in Europe and extremely confused about why he was getting angry calls from high-level state officials. (They agreed that the tweet wasn’t worth it; she took it down.) When asked about this event, DeRosa said, “I was defending a staff member who was doing his job and was being maligned. It’s well known I’ve had plenty of tough conversations with men and women over the years, and to attempt to somehow paint this as gendered is demonstrably false.”

The administration still seems unaware of the irony: The very point Rivera had been making about Azzopardi — that his white male privilege insulated him from repercussion when he attacked women of color — was proved by the wrath the administration brought down on Rivera, a woman of color.

In 2015, Camonghne Felix was a 23-year-old activist and poet, trying to figure out how to make change in the world after her work with Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter, when a friend told her that the governor was looking to hire a speechwriter who had a background in poetry. Felix imagined that her organizing background would kill her chances.

But Mario Cuomo had recently died, and one of his most famous proclamations had been that you “campaign in poetry; you govern in prose.” His son, mourning a father whose legacy he has long been obsessed with besting, wanted poetry. Felix was told she would be hired within 24 hours of her interview. “I probably wrote about 30 speeches or sets of remarks for him, and I think he used one,” she says now. “My desk was close to his office. He loved to see me, but he didn’t listen to a single word I ever said.”

Felix was the first Black woman to work as a speechwriter for Cuomo and was the only Black person on the press team, where she later worked in communications after accepting that he was never going to use her speeches. “It’s a very subtle form of racialized abuse,” she said. “You know I am beneficial to you. I fill a quota. It looks good on paper, and we made sure to put press releases out. But you don’t intend to incorporate me into government. You just like to show me to people.”

Partway through her tenure, Felix got a new boss, a man she said was treated horribly by his superiors. One day, Felix made a mistake on a press release. “He called me and said, ‘What the fuck is wrong with you? How fucking could you?’ The first thing I thought was, Oh, this must be how Cuomo talks to him. Because it didn’t even make sense. It didn’t seem natural to this guy. Like, I don’t know where you got all that bass in your voice.”

“Azzopardi, Melissa … it’s like he inhabits them,” said Bill Lipton, a founder of the Working Families Party. “When they call, you can feel his presence. They’re screaming at you, and either he’s right there or you can feel that he’s just yelled at them and they’re giving it to you.” When asked to provide comment on the claims made in this article, Azzopardi, their spokesperson, responded, “There is no secret these are tough jobs, and the work is demanding, but we have a top-tier team with many employees who have been here for years and many others who have left and returned because they know the work we do matters.”

Felix believed that in certain instances, Cuomo — and certainly the people who worked for him — had good ideas. “But you were never able to implement any of them because the culture within his staff was so violent and corrosive that people can’t get anything done without cheating, without cruelty, without bribery.” Days before news broke that Cuomo’s staff had altered the nursing-homes report, Felix had observed to me: “You have to imagine that people do bad things, corrupt things, because they feel like they don’t have a choice. There’s so much fear all the time. That’s bad because it stops not just progress; it stops government from efficient governing.”

“It’s how you are groomed to do the job,” another longtime administration veteran told me. “If you need to publicly shame someone, that’s okay. If you need to berate someone in front of their peers, that’s acceptable.” She described the explicit ethos as: “Either you can win, or you can lose.”

For Cuomo, many people told me, a big part of winning means lying. “I was taught that it was totally fine to lie,” said Ana Liss. “Even as a peon, I was part of some of the lies and mischaracterization.” After the story of the nursing-home scandal broke, DeRosa was caught on tape acknowledging that data had been hidden to avoid attacks from the Trump administration, and subsequent reporting has shown that she and two of Cuomo’s other close advisers purposefully altered documents to obscure the truth.

“He makes things up like I’ve never seen anyone do before,” said Lipton. “He makes people who disagree with him feel like they’re crazy.” It’s a pattern that — like his narcissism, theatrical bombast, love of cameras, hatred of “experts,” and the fact that, as one national reporter who covered him said, “I don’t think he believes in much, except that he wants to be powerful”—makes Cuomo not the anti-Trump that many imagined him, but rather the 45th president’s Democratic twin. Or, as one person put it to me, they are “the same person” but for “two major exceptions: Fred Trump was Donald Trump’s father, and Mario Cuomo was Andrew Cuomo’s father.”

Cuomo’s Jedi Mind Trick approach to public narrative undergirds his ongoing feud with New York’s WFP. The minor party — which is allowed to cross-endorse candidates, creating pressure from the left without having to run spoilers — has been critical of Cuomo since his first term, when, after running as a progressive, he enacted corporate-friendly economic policy, obstructed Mayor de Blasio’s attempt to tax the city’s wealthiest residents, capped property taxes at 2 percent, and, many of his critics alleged, tacitly allied with state Republicans and the Democratic Independent Conference (IDC), a cabal of conservative Democrats, to keep the State Legislature out of Democratic control. It was an arrangement that — along with the tax caps that kept shrinking the state’s budget — permitted Cuomo to blame the stagnation of progressive initiatives on a snarled Legislature. (Cuomo has long denied that he supported either Republican or IDC control of the Legislature).

In 2014, after almost endorsing his primary opponent, Zephyr Teachout, the WFP cut a deal with Cuomo in which, in exchange for their support, he promised that he’d work to dissolve the IDC, raise the minimum wage, make the Dream Act state law, and expand abortion access in the state. But he simply didn’t follow through on his vows, and in the wake of the WFP’s endorsement, he acted like he’d landed a knockout punch rather than submitted to an agreement, telling a reporter, “You either win or you lose, and I won.” Cuomo then launched his own minor party, naming it the Women’s Equality Party, or WEP, perhaps to confuse voters and sap power from the WFP. Though the WEP endorsed Cuomo over Teachout (a woman) and would in 2018 endorse him over Cynthia Nixon (also a woman), it branded itself as committed to women’s equality by commandeering a pink-striped bus.

When, in 2018, the WFP supported a group of candidates, many of them young, many female, many candidates of color, who finally defeated the IDC and put the Legislature back in Democratic hands, Cuomo responded by raising the threshold of votes that a minor party needs to stay on the ballot. “When we elected a new class of leaders who had a very different orientation to power,” said Sochie Nnaemeka, director of the WFP, “the governor struck back by trying to kill the party.”

It didn’t work. The 2018 cycle would mark a turning point in Cuomo’s ability to terrify his would-be challengers into silence and submission.

In 2016, Alessandra Biaggi, a lawyer who had interned for Joe Crowley, worked on the Clinton campaign, and was the granddaughter of the late New York congressman Mario Biaggi, took a job for Cuomo’s then–chief counsel, Alphonso David. She entered the administration, she said, thinking, “I’m a lawyer for the governor of New York, now the progressive beacon of the world.”

Within a couple of weeks of joining the administration, she was at a party at the governor’s mansion. “The governor comes over to me and grabs my elbow,” she said. “He didn’t say ‘Welcome’ or ‘Thank you for being here.’ He said ‘Nice dance moves’ and walked away.” The male colleague standing next to her said, “ ‘What the fuck was that?’ ”

Biaggi said that she did not feel in that moment that she was being sexually harassed. “I just felt like it was so weird. That was my first interaction with him, and I didn’t know what to think except, Okay, this is the governor of New York, and I am here to do my job.”

The job was a lot less beacon-of-progressivism-y than Biaggi had anticipated. She was focused on an immigration bill and on the Reproductive Health Act, which would codify Roe v. Wade as state law and expand access to abortion care. Biaggi and others believed that the law was finally going to pass in the wake of Trump’s victory; it was never even brought to the floor. At the time, she couldn’t quite figure out why. “Part of what makes Cuomo powerful,” she said, “is that there’s no information sharing. It allows him to evade responsibility; nobody really knows what’s going on.”

Biaggi said she asked her boss about it. “I remember Alphonso saying, ‘Yeah, you know, that’s Albany.’ ” She was put off by what she saw as a sluggish disconnect from the urgency of the moment, especially within an administration that was supposedly mounting vigorous opposition to Trumpism. “Every day, Donald Trump was pushing some executive order and no one in this office was taking it seriously,” said Biaggi. “They were yanking around all the advocates and pretending to care, but nothing ever got anywhere. It was just showmanship, the veneer of governance.”

After learning more about the IDC, led by Jeff Klein, the conservative Democrat who had also been accused of sexual harassment by a staffer (a claim he denies), Biaggi had coffee with Mike Gianaris, a Democratic state senator who was understood by members of the administration to be strategizing to unseat the IDC. They discussed the possibility of Biaggi running against Klein. “I was full of rage after 2016, Trump being president, Hillary losing. I was dying to use my brain to do good work.”

When members of the administration found out about the coffee, they did not respond warmly. Biaggi’s boss, she said, called her 20 times in a single weekend, quizzing her aggressively about her coffee with Gianaris. “The incessantness of the calls was scary,” she said. Then, in a Monday meeting, she remembered, her colleagues laughed at the idea of her challenging Klein. “I swear to God that was the moment when I was like, I don’t care, I’m running.” (David does not recall making 20 calls in one weekend.)

After leaving Cuomo’s office to launch her campaign, Biaggi didn’t see the governor until August 2018, when they both attended a wedding. “He says ‘Hi, Alessandra,’ pulls me in, and kisses my head twice and then my eye. He’s holding on to my arm, and he looks at my fiancé and says, ‘Are you jealous?’ ” Again, Biaggi said, “I didn’t feel sexually harassed. I felt like he was trying to make me feel uncomfortable, to disarm me.”

Biaggi won her primary against Klein in September 2018; she didn’t hear from Cuomo. But on the day before the general election, she got a call from his office, telling her that the governor wanted to see her. Biaggi brought two campaign staffers along with her, but Cuomo’s staff did not permit them to accompany her into the room, where he was sitting with DeRosa. Biaggi said that most of her conversation with Cuomo was normal and nice, until the end when “his whole demeanor changed and he sat back in his chair, looked at me, and said, ‘Tell me again how your grandfather’s career ended?’ ”

Mario Biaggi’s career ended with a 26-month prison term for having accepted an illegal gratuity and obstructing justice. Thirty years later, his granddaughter said she stared at the governor of New York and willed herself not to “freak out, because he wants you to freak out.” Biaggi felt sure that Cuomo had been conveying a threat, though its specific contours were confusing. “What is he telling me? That he’s going to send me to prison? That he’s so powerful he could end my career?”

The sheer amount of interpersonal drama, anxiety, and rancor that former Cuomo staffers described was wholly exhausting, like something from The Devil Wears Prada.

Multiple people told me that they began therapy and antidepressants for the first time in their lives while working for Cuomo. Ana Liss said that she “started pursuing mental-health services when I was there because I thought I was going crazy. My parents thought I was going nuts. I was angry and crying all the time, and I went on Lexapro.” At one point, she said, “I did call in to a suicide hotline because I felt like such a friggin’ nobody.”

On December 31, Cuomo lavishly opened Moynihan Train Hall; the $1.6 billion conversion of the former post office had been overseen by Michael Evans, who had faced steadily mounting pressure to finish it and who took his own life in March 2020. Evans’ partner, Brian Lutz, told me that “it would be unfair to lay all of the blame for Michael’s death at the feet of Andrew Cuomo. Michael made a lot of choices over the course of his life that served as kindling, but Governor Cuomo and his administration lit the match.” The governor, Lutz said, caused his late partner “psychological terror” and made him feel “constantly afraid.” In some of the last texts of his life, Lutz said, Michael told him that he was “afraid they would destroy his career.” (A Cuomo spokesperson responded that Evans had met directly with Cuomo five times in the three years before his death, cited appreciative statements made by the governor at the Moynihan Hall, and noted that “he has a plaque in his honor at the station.”)

Those beaten down by the vicious workplace were also depressed that none of their misery was in service of effective governance or better policy. In fact, many told me, there was little interest in policy. “It was policy-making like paint-by-numbers,” said one former staffer. “The goal was superficial, as opposed to changing people’s lives. It was heartbreaking.” That didn’t mean that policy didn’t get enacted, she said, but it was second to and in service of optics. “Someone from the inner circle would call and say, ‘The governor wants to go to Orange County. What can we announce?’ ”

Wertheimer, who put together the governor’s daily briefing book and said that Cuomo rarely even read policy memos, agreed. Cuomo and his senior staff were obsessed, said several sources, with the annual “State of the State” book, which showcased task forces, pilot programs, and funding commitments, some of which were only tenuously rooted in reality. “The whole endeavor seemed to be about size,” said one person who worked on it. “Like if you have a big book, it shows you’re going to do a lot of things.” She said that the notion that “governing was about solving problems and making people’s lives better was not what drove people inside that building … but when you objected to the shoddiness of a job or refused to do something unethical, it was because you couldn’t hang. I was like, Fuck you. It’s not that I can’t hang. It’s that you all are terrible people.”

The idea that you had to be able to submit to abuse in order to work with New York’s executive branch drove out not just staffers but external experts. Andy Byford, the British transportation guru hired in 2018 to update New York City’s crumbling subway system, left just two years later, making it clear that Cuomo had made the job impossible. “I was not going to be allowed to get done what needed to be done,” he told the press at the time. “I just would not accept the fact that my people were being yelled at.”

One former staffer who worked in the administration described a morning on which she’d been awakened at six; she spent the workday, till 11 p.m., too afraid to leave her computer “even to eat or go to the bathroom,” getting steadily castigated over email by DeRosa. A week later, she said, DeRosa came into the office “and introduced herself for the fourth time. I had worked with her for two years at that point.”

Not knowing people’s names wasn’t just incompetence; it was another signal of dominance. When Cuomo ran against progressive law professor Zephyr Teachout in 2014, he pointedly refused to say her name, make eye contact, or shake her hand at a parade. “It’s embarrassing to have somebody treat you like that, like you don’t exist,” Teachout told me.

It often worked, instilling a conviction in many that they had no worth and that therefore there would be no point in fighting back or speaking out. Most people who spoke for this story told me that they were hesitant to come forward precisely because they could imagine how their accounts would be rebutted by the administration: that no one remembered that they’d even existed. Some who worried about this were staffers who’d worked alongside DeRosa and Cuomo every day for years.

This was how people in the administration were taught to behave, said Camonghne Felix. “You had to subjugate someone.” These are, of course, the strategies that reinforce capitalism and brutal political regimes: Authority is created and strengthened through the diminishment and depletion of others. Too often, those in power wind up spending more time performing muscularity than actually doing whatever it is they’re supposed to be dominant at doing. As Felix said, “The state gets trapped in this cyclical nonsense. You look up and see that nothing is getting done. And not only that: Things are getting broken.”

How could so much of Cuomo’s bad behavior have remained normalized, even admired, through three terms? He has stayed extremely popular with the public, his approval soaring through COVID. Even some of his harshest critics are careful to acknowledge good things about him, mentioning the legalization of same-sex marriage, his work to protect nail-salon workers, an early expansion of Medicaid to undocumented immigrants (he has since pushed punishing cuts to eligibility). Others commend him for closing multiple prisons and his willingness to raise the minimum wage.

But critics point out that many of his accomplishments — including the minimum-wage hike, the eventual passage of the Reproductive Health Act, and his investment in offshore wind — only happened after years of delay, where Cuomo himself played obstructionist as people and the environment suffered, until a time came when glory could redound to him personally.

Cuomo’s conduct could also remain camouflaged in a state capital known for the grotesquely antiquated and unjust hierarchies it thrives on. As one woman who worked in Cuomo’s counsel office early in his tenure told me, “Albany felt like a seedy adult summer camp.”

Yuh-Line Niou, a staffer for Assemblymember Kim before winning office herself (doubling Asian American representation in Albany), spoke of how she had her ass grabbed in an elevator by an elected official within her first week in town; she was 27 and also recalled an assemblymember who approached her and Kim at a fund-raiser and said, “ ‘I can’t believe you guys haven’t fucked, I would fuck both of you and I would pay to see you two fuck; I would pay to join.’ ” She said that Kim was so conscious of how much harassment she endured that when they were in Albany, he’d always offer to grab her lunch so she wouldn’t have to venture out alone.

If the town is rough, the press corps that covers it doesn’t offer enlightened salvation. “You walk into the Legislative Correspondents Association, and it’s largely men and largely white men,” said Amy Spitalnick, who worked as the New York attorney general’s communications director and senior policy adviser from 2016 to 2019. “There are very tangible impacts of that on how our government is covered: what is deemed permissible and what rises to the level of attention. Which is why all of this has been an open secret for so long.” There are women in the press corps, but, Spitalnick said, “they can get burned out,” in part because of the aggression they face from Cuomo. In 2012, it was reported that the administration kept a 35-page dossier on journalist Liz Benjamin, who two years ago left her job hosting Capital Tonight. Another reporter, Lindsay Nielsen, wrote recently about how, in 2017, she left her job covering politics for the Albany-based News10 after five years of “threatening” and “incessant bullying” from the Cuomo administration.

As the story of Cuomo’s tactics gets reported in a more critical light, Josefa Velásquez, a 29-year old senior reporter for The City, said that she sometimes considers how some colleagues, including some of those now covering Cuomo’s troubles, “never used the power that they had to defend anyone else before this.” She’s referring to both reporters and some of the governor’s advisers. “No one checked him. He’s the governor of New York who has consolidated all this power and has all these political allies. But his aides and the men in the press corps, some of them are just as complicit in this behavior.”

There are a few hundred people at least — insiders in Albany, in media, in labor — who have known how Cuomo operates for years. And then there are tens of millions who just really love him on TV.

It may have been the television adoration that precipitated the fall. In March, Cuomo began conducting his daily press briefings, performing charismatic calm in the face of panicky instability, ticking off daily numbers to combat the unknown; his updates became a soothing ritual. As Trump lied and tantrumed and overrode experts, Cuomo — a man of similar habits — was received as a competent balm.

His long-simmering power contest with Mayor de Blasio crested in March and into April, as they locked antlers over when to shut businesses, whether to shut schools. In April, Cuomo joked on Ellen about people calling themselves “Cuomosexuals,” and in May, appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone, solemn pandemic rock star. In a June briefing, he unveiled a foam replica of the COVID curve — “the mountain that New Yorkers climbed” — and in July, his administration printed the NEW YORK TOUGH posters featuring himself and DeRosa, who was labeled “Magnificent Melissa.” In August, he announced a book deal, reportedly worth seven figures, to write about his experience leading through COVID. In October, as his book, American Crisis, was published, his name was floated to be Joe Biden’s AG. In November, he won an Emmy for his briefings.

Behind the scenes in those first weeks of COVID, Cuomo was making the unprecedented move of expanding his emergency powers beyond those of any New York governor since Nelson Rockefeller. Into the massive state budget, he inserted an immunity provision for hospitals and nursing homes; the provision had been drafted by the Greater New York Hospital Association, an organization that, in 2018, donated over a million dollars to the New York State Democratic Committee (which funded Cuomo’s reelection campaign) and was repped by Bolton-St. Johns, a powerful firm where the chief lobbyist is Giorgio DeRosa, Melissa DeRosa’s father. In a particularly bitter irony for those who’d envisioned New York State government as the lab for progressive federal policy, the state’s “gold standard” corporate immunity law would indeed wind up a model — for Mitch McConnell.

Cuomo pooh-poohed “experts” in science and medicine, eventually driving out nine of the state’s top public-health officials. A Columbia University study would show that his dickering with de Blasio and ensuing delay in locking down New York likely cost 17,000 lives. In June, his aides were reportedly altering the nursing-home documents. That same month, Charlotte Bennett alleges that Cuomo was asking her whether or not she had ever had sex with older men.

Just as Cuomo, who had long exerted such punishing and obsessive control over so many, was coming close to what he had always sought — the expansion of his power, the eclipse of his father’s legacy, a firm spot on the national stage and in the American imagination — he was starting to lose his grip on the political forces within his own state.

When Biaggi beat Klein in 2018, she was part of a group of new legislators — including Jessica Ramos, Zellnor Myrie, Rachel May, John Liu, Julia Salazar, and Robert Jackson (all backed by the Working Families Party) — who finally rid the state of the IDC. “People are not impressed by political machines anymore,” said WFP’s Nnaemeka. “They are inspired by leaders who are connected to the community.” What is threatening, she said, “to this masculinist closed-door politics is democratic participation, leaders propelled by people and not by institutional ladders … The day of those politics is over.”

“Part of my healing,” said one former member of Cuomo’s staff, “came when Alessandra won and when she started to confront him and not fear him.” Many in Cuomoland saw the victory of Biaggi as a stand-in for victory over Cuomo himself.

It’s not just the young left wiggling out from under his thumb. After eight years in which State Senate Republicans, with help from the IDC and Cuomo, kept Democrats from control of the Legislature, and their leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins out of budget meetings, Stewart-Cousins is now in power. On March 6, she called for Cuomo’s resignation.

Then there’s Tish James. When James was first elected to City Council in 2003, she was the first candidate ever to win a race solely on the WFP ticket and stayed affiliated with the party through her tenure as public advocate. When she ran for attorney general in 2018, James accepted Cuomo’s powerful backing in exchange for not running on the WFP line. Now in office, she has not behaved like a politician bought and paid for by Cuomo. James released the nursing-homes report and is one of the candidates who could, should Cuomo survive this period, mount a formidable challenge to the fourth term he has been hell-bent on pursuing.

Cuomo is also being challenged by his former staffers, who are now speaking out. They are a reminder that the problem with dismissive assumptions about hierarchical power is that you often underestimate those you are oppressing and overestimate your ability to suppress them; a reliance on divisive mean-girl machinations can keep you from seeing how women might one day come together to challenge your power.

Niou told me of how long she’d spent, even after winning office in 2016, feeling exactly what Cuomo wanted her to feel: like a nobody. “They could just knock me out, the only Asian woman, and nobody would notice. They’ve known they can say something and that I have to grin and bear it because I don’t have any power over them. That’s the stuff they tell you to believe.” What’s changing, Niou said, “is that I am now part of a cohort of people who are speaking up. And it’s starting to matter.”

New York’s newer model of politics surely is not perfect, nor immune to abuse, nor made of inherently finer stuff; Biaggi is, after all, the product of a political dynasty herself. But it is indisputably built around a different posture toward power.

That posture alters the dynamics of dependence and fear. In very practical terms, these new politicians do not owe Cuomo or his administration anything; their power was gained in spite of him, and while his administration can still starve their districts in retribution, an ability to describe that openly gives them a freedom previous generations have not had. Biaggi told me that she has even blocked DeRosa’s number. “I don’t want that bad energy,” she said.

One impression that emerges from Cuomo’s ten years in office is of an immense amount of time wasted. Biaggi said that on the day after Amazon pulled out of its deal to open in New York City, she received a call at 9:30 a.m. from Cuomo, upset at her for having been critical of his handling of the deal. What struck her was that “he was more concerned with calling me than with the aftermath of Amazon leaving. He spends his days yelling at people who say bad things about him, rather than governing.”

For an awfully long time, we have accepted the indignities and mediocrity of brute white patriarchy as our only option, both because we couldn’t imagine better and because even the act of pointing out that it should be better felt futile. And so this kind of power could be petty, corrupt, threatening, skeezy; it could be handsy at weddings and harassing at the office; it could lie and cover up and be sent to jail and still it would be our norm and all we had to turn to in a storm, through a pandemic. We had to pin our hopes on it as a refuge from other, worse brutal white patriarchs. And so we learned to love it, to tune in to its daily briefings and allow its self-assuredness to wash over us.

While I was reporting this article, I spoke to one woman who told me of a time Cuomo hit on her at a party years ago. It wasn’t the story of anything illegal, just an invasive and brash move, made a few feet from where his then-wife was standing. She described to me how he’d learned her name before approaching her, how he’d taken hold of her hand and not let go, had whispered close into her ear, how he’d come on to her: “It was clear when he grabbed me that he was used to taking what he wanted.”

In an earlier era, I could imagine that line being used in a romance novel, an affirmative description of sex appeal. In this era, in which we have been offered new language, more autonomy, and better therapy, such a description has lost its sexiness for many women, including the woman in question, who did not respond warmly to Cuomo’s overture but rather froze, because his attitude — even in this comparatively ordinary interaction — had given her terrible flashbacks to the sexualized violence of her past.

Until this week — when an allegation of groping was referred to police and Democrats in the Legislature initiated the first step toward impeachment — it seemed quite possible that Cuomo’s governorship would survive. So far, Cuomo has refused to entertain calls for his resignation, instead requesting an investigation and circulating a statement, which he asked female lawmakers to sign, suggesting that calls on him to step down are tantamount to undermining Tish James. It’s a classic Cuomo defensive deployment of feminism and one of many signs that he is not going down without a probably very ugly fight. As he has so often in the past, Cuomo might well win that fight. But with more than 55 lawmakers in his party calling on him to step down, it is harder than it has ever been to imagine him winning a fourth term, or fashioning himself into a national political figure, or continuing to exert the stranglehold on his state and party that he has become accustomed to. In that sense, what we are witnessing, after a year of meteoric rise, is the extraordinary, crashing two-month fall of a man whose power, for a decade, has been almost total.

The brutality that Andrew Cuomo has brought to politics — connected as it has long been to his authority and his ability to take whatever he wants from his staff and his state — has, like his sexualized advances, been drained of a lot of its appeal.

We didn’t know we had an alternative. Now, it seems, we might have many.

Additional reporting by Jane Starr Drinkard and Amelia Schonbek.

More on andrew cuomo

- The Heavy Hitters Who Could Run to Succeed Eric Adams

- Eric Adams’s Strategy to Hang On

- Andrew Cuomo Wants the Kind of Redemption That Comes From Winning an Election