This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

One thousand nine hundred and fifty-four miles, from the Pacific to the Gulf, where people live and work. Where they commute between Mexico and the United States like they commute between New Jersey and New York, passing through a security checkpoint as they would a toll outside the Holland Tunnel. Where you may look in the distance to mountains and valleys and ask where one country ends and the other begins. Where you may start to wonder about the nature of such distinctions, about the nature of separateness, about the nature of self, about borders between men, between man and state, between civilization and disorder. Where you may appreciate just how young a species we are and how tribal. If you have never stood on the banks of the Rio Grande in Texas or the Colorado River in Arizona, if you have never come face-to-face with the wall, 30 feet high, that looms multiples higher in our national psyche, if you have never put your hand through its steel tines and reached into Mexico, if you have never thrown away your bubble gum in Juárez because you cannot chew gum and walk into the United States at the same time, per the signage at Customs, the boundary between countries can seem ominous and alien, an uninhabitable space somewhere between the end of America and the end of the earth.

And then you get there and there’s a Starbucks.

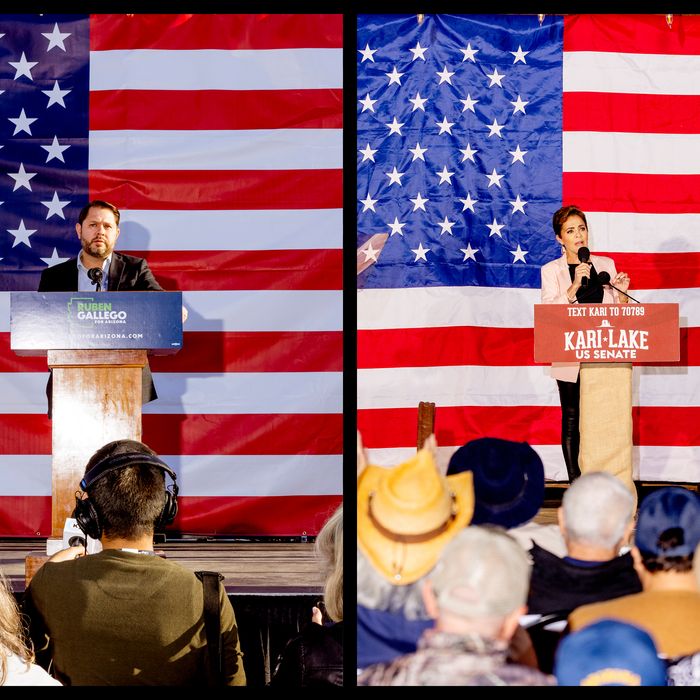

Congressman Ruben Gallego laughed. “When I tell people that the border has a Starbucks, it weirds them out,” he said. “All they think about the border is that it’s like this war zone. It’s not.” Gallego deployed in 2005 during the third wave of Operation Iraqi Freedom. His infantry unit, Lima Company, suffered more combat losses than any other Marine unit throughout the war. Almost 20 years later, he still has survivor’s guilt. And PTSD. And fixed opinions about what can and cannot reasonably be compared to war. “There’s definitely problems,” he said. “But this is what the border is: People who live on the border, who didn’t come here to protest the border. People that want border security but also want immigration reform. People that want to make sure that we stop people from crossing the border illegally but at the same time want to make sure that the ports of entry are open so we can bring business through. They want to make sure that we uphold our American values, but they also don’t like being made to feel that they’re not part of this country when people call them just a ‘border community’ or some kind of dangerous ‘Cartel Land,’ like Kari Lake does.”

It was 11 a.m. on a Saturday in December, and Gallego was in Somerton, a city in Yuma County on the southwestern edge of Arizona. If drug dealers and rapists and other criminals were at this very moment barreling onto American soil, you couldn’t see them from where he was standing. No, this was the Democratic border pastoral. A patchwork of strip malls, reservations, charming houses, and 230,000 acres of what they call desert agriculture, irrigated by the Colorado and tended to by 15,000 migrant workers who cross the border from Mexico each morning and cross back at the end of the day. So that in winter you can order the Bibb lettuce at a restaurant in New York for $23, or the cost of an hour and a half of manual labor here. The sun was shining. At the horizon, the gravitational border painted a Rothko where the verdant fields met the clear blue sky. Children skipped through the park. Couples walked their dogs. And Gallego, preparing to judge a tamale competition, which is the kind of thing you do here when you’re running for the U.S. Senate, was operating on Red Skelton time. Which is to say he was making his way to the bar. Which was not his idea, he wanted to be clear, but it was a good idea, and he was nothing if not the kind of diplomat who would adopt good ideas whether or not they were his own.

He nodded in the direction of Gerardo Anaya, Somerton’s chief executive. “So the mayor wants us to go, uh, test the margaritas,” he said, leaning forward to address his campaign aides in a mock-conspiratorial tone. “He’s insisting we go to margaritas. It’s tradition here!” His own bright idea had been to start the day with a breakfast sandwich from the border Starbucks — “a palate cleanser,” his spokeswoman cracked, for the 26 tamales he would have to consume to perform his solemn duty — and the implications of that decision were beginning to dawn on him. But the behavior of past Ruben Gallego would be a problem only for future Ruben Gallego; current Ruben Gallego had to focus. If the people of Arizona were going to elect him in November to replace Kyrsten Sinema, he would have to prove himself. Partial to bourbon, he would first have to make an exception to observe victual customs that prescribe tequila. Then he would have to eat a lot of tamales.

He grinned. This was the fun part of running for office: traveling 200 miles from Phoenix, where he lives and where since 2015 he has represented Arizona as a low-profile Democratic member of Congress, to pay his respects to the rest of the state ahead of a Senate race that could be the most consequential of 2024. Sinema, who in 2022 defected from the Democratic Party to become an independent, had spent the winter negotiating a border deal that would fall apart amid a Republican sabotage plot led by Donald Trump; after that defeat, she announced that the American system was nonfunctional, that it was impossible to get anything done that was not in service to the zero-sum game of hyperpartisan politics, and that she was giving up on the vocation altogether.

She ceded the race to Gallego and to Lake, a former anchor on Fox 10 Phoenix, well known in the state and beloved on the far right for her commitment to a narrative about election fraud, in which Arizona was the site of a vast conspiracy to stop well-meaning people from Keeping America Great in the 2020 election, when Joe Biden barely won here, and then from Making America Great Again (Again) in 2022, when Lake ran for governor and barely lost. She devoted the intervening years to well-publicized legal challenges that are ongoing.

President Biden and the former president are both campaigning on what Trump promises he will do if he claws his way back to the White House: exert control over government agencies, including the Justice Department, through a sweeping expansion of executive authority to exact revenge on his political enemies and law-enforcement tormentors and rewrite the violent history of his failed attempt to overturn the results of the 2020 election. Thanks to Arizona’s dual status as one of six swing states that will decide the presidency and one of three states where so-called toss-up Senate contests will decide control of the upper chamber of the legislature, voters here are in the unusual position to potentially determine who leads the American government and how much power that leader may have to execute his will.

Trump’s political persecution is only part of a larger story Republicans are telling about the rule of law in America. It’s the story of economic globalization and the sins of late capitalism distorted through the dictatorial prism of race, in which a corrupt Establishment has rigged the system against them, allowing or outright inviting crime, organized and individual, to spread arterially from the border into cities, into the heartland, and into the center of a government that sells out its citizens to adversaries who take their jobs, their security, their sense of pride, their pride in country.

It’s a simple story: They are coming for Us. And it’s a story Trump has been telling since he began his career as a presidential candidate nine years ago. Gallego and Lake, then, are acting in a novela much bigger than their own campaigns. Against the backdrop of the border, the issue voters here say they care about more than anything else, they have been cast as proxies for two oppositional realities competing for supremacy.

The few head-to-head surveys that exist suggest Gallego maintains an advantage over Lake — for now. More instructive may be the polls that, since November, have shown Trump ahead of Biden by an average of five percentage points. When Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Jill Stein, and Cornel West are factored in, Trump’s lead climbs to nearly six points (a super-PAC supporting Kennedy’s campaign says it has submitted enough signatures to qualify for ballot access in the state; the Green Party and Libertarian Party are already on the ballot, while West’s status remains in doubt). For now, the best guess, as a senior adviser to the Lake campaign explained it, is that “Biden and Ruben or Trump and Kari will sink or swim together.”

Gallego took short, quick strides across the pavement, stopping to chat in English and Spanish with anyone who wanted to stop to chat in English or Spanish. Promoters billed the festival as “the Woodstock of tamale events.” Gallego surveyed the scene with the authority afforded to a second-generation American son of a Colombian mother and Mexican father, who spent summer breaks from his school outside Chicago in the mountains of Chihuahua, where he tamed a wild coyote and tended to the beans, watermelon, and corn growing on the family farm. Over the course of his 44 years, he estimates, he had “made thousands of tamales” and learned a thing or two: “There is right and wrong, good and evil, and there are such things as good and bad tamales.”

Gallego paid for his cocktail in cash, held the plastic cup in the air, and let the rituals begin. “After this, we go to the Chinese restaurant and — I kid you not — that’s where we’re gonna test all the tamales. Then we’re gonna to cross the border and get Ozempic,” he joked. “It’s out of stock everywhere.”

At the convention center in downtown Phoenix the following day, all signs pointed to a Donald Trump rally: The swarms of star-spangled white people snaking their way through the security checkpoints. The red MAGA hats blooming on their heads. The imagined presence of the stalking villains (Hillary, Obama, Biden, Kamala, the Deep State) and the real presence of the disciples (Don Jr., Marjorie Taylor Greene, Roger Stone, Roseanne Barr) who battle in his comic-book world. The only thing missing was Donald Trump himself, who was campaigning 700 miles away in Reno.

This was AmericaFest, a four-day procession of speeches, panels, and parties programmed by Turning Point USA’s Charlie Kirk as a kind of MAGA-con, a Conservative Political Action Conference without the baggage of modern conservative history, as if every iteration of the American right from 1980 to 2016 had evolved in mythic error as a Period of Kings, and now American meant Trumpian and patriotism meant a pledge of allegiance to MAGA and MAGA alone.

An enterprising Eagle Scout with Alex P. Keaton verve that made him a rising star of the Obama-era right, Kirk was savvy enough to throw in with Trump as he secured the Republican nomination in 2016 and a skilled enough operator to reap from Trump’s good political fortune a fortune of his own. Now 30 years old, Kirk is as popular among zoomers who want to own the libs as he is among boomers impressed by his role in the great ensemble that forms a protective membrane around the former president. Turning Point, functionally a Christian-nationalist recruitment organization for student activists headquartered in Phoenix, is his kingdom of profit and influence, and AmericaFest is yet more proof that when attachment to a personality is strong enough, the cult does not require the attendance of its leader to hold its services. The tribute acts will do.

Onstage in a crowded conference room, Kirk introduced the man he called “one of the generals of the MAGA movement.” Steve Bannon looked satisfied. The former Breitbart chairman, Trump White House adviser (for a season), and host of the War Room podcast has become a kind of philosophical influencer for a terminally online faction of the MAGA base. “The forces aligned against us are only getting more serious and more severe,” he told Kirk, “and when I say there’s no middle ground, there’s no middle ground. One side’s gonna win here, and one side’s gonna lose.” The macho language of war is pervasive in politics, but Bannon, a Navy veteran who looks like the skipper of the underworld, seems to really mean it.

Under the thumb of the elite ruling class, the country was going to shit, he said, and that was by design. And with MAGA “ascendant” once again, the elites were “panicked” and “desperate,” scrambling to weaponize the nation’s powerful institutions against movement leaders to strike fear in the hearts of the congregation. “They are converging the Central Bank, the lords of easy money on Wall Street, the tech oligarchs, the national security apparatus, the legal apparatus,” Bannon said. He anticipated high drama in the election. “This next year, you’re going to see things you’ve never seen in your life — in any country,” he said, his voice vibrating with awe. “To try to stop this movement.”

“Including assassination attempts?” Kirk asked.

Bannon thought so and cited as proof a Washington Post column by Robert Kagan that compared Trump to Julius Caesar. In his view, what Kagan was really doing was sending yet another signal — a green light — to anyone inclined to try: “I’ve also heard from some donors that there’s been loose talk in Democratic social settings, Republican social settings, that they’re tossing out the concept of assassination, figuring out if they can decapitate our movement.”

Kirk lived in a state of constant fear, he said, that he would wake up one morning soon to the news that they’d done it. But Bannon had a good argument to deter would-be assassins: Even if they did it, he said, it wouldn’t work. Not really. You can’t kill Trump. The movement had already made him immortal.

As pressing as concerns that they might attempt to steal Trump’s life were concerns that they might attempt to steal his election. The whole room was in agreement that it had already happened once. “They stole the election, and they’re petrified of us getting in there and finding that out,” Bannon said. “In Arizona, we’re sitting on ground zero.”

After the talk, Bannon split, escaping behind the stage with his entourage. Down the hall, they slipped into Meeting Room 132B, the kind of big, overly air-conditioned space you might find yourself in at some awful luncheon you agreed to go to for reasons you cannot recall, trapped and hiding near the coffee urns in the back from the people in name tags whom you now consider your sworn enemies. I’m guessing. On this occasion, the space would serve as Bannon’s one-man writer’s room. In about an hour, at 5:50 p.m., he was scheduled to deliver a speech he had not yet started writing to a crowd of 13,000. He grabbed a Red Bull, a legal pad, and one of the (three) Uni-ball 207 Impact Gel pens he keeps clipped to his surface-most Orvis shirt of the three, at minimum, he always wears. He wasn’t worried about the deadline, he said. He always pulled it off. The room got quiet. Bannon scrawled on the legal pad. He paced around. He sat down to scrawl some more.

Then Kari Lake walked in. Bannon snapped to attention, rising to greet her. Dressed in a brown velvet cocktail dress and nude patent stilettos, Lake buzzed with cheerful energy, her white teeth gleaming beneath the fluorescent lights. She was trailed by her own small entourage of aides and a friend named Brandie Barclay, whom she calls her “prayer warrior.” Lake told Bannon that Barclay had just told her something interesting: During her speech that night, she needed to “call the Lord in with love,” a departure from her usual “rabblerousing.” Bannon laughed. “This is a new Kari Lake,” he said. “I’ll tell ya. 2.0! She’s so worried about love!” Lake laughed, if a bit defensively. “I’m teasing, I’m teasing,” Bannon said.

“Believe me!,” Lake said. “Right now, we have, like, three speeches that I’m using, and one of them is like, argh!” — indicating a certain ferocity — “and I don’t know, I’m just not feeling it. I’m like, ‘Let’s change it!’” Bannon joked about falling asleep in the greenroom listening to whatever she decided to go with. Lake eyed him curiously. “So,” she said, “what are you gonna do?” Before he could respond, she answered her own question, her voice taking on a playful, musical quality. “You have noooo idea, do you?” Bannon smirked. “I’m gonna think about it right now,” he said. Lake had a better idea. “Guys!” she said. “Let’s — can we all do a prayer right now?”

With that, the group moved synchronously into a circle. They grabbed hold of one another’s hands. Bannon took Lake’s hand in his and looped it around to rest on his lower back. She gripped him tightly, her knuckles turning white. They kept their hands there as they closed their eyes and bowed their heads. Barclay did the honors: “Thank you so much, Father, for the champions you have brought together in this room. We know that you are with us and working for us. I pray, Father, by the blood that your son shed on the Cross, just cover the people in this room, especially the voices of Steve and Kari, that your power would just breathe on the crowd, that they would lay themselves down and allow you to just move through them.” Barclay told the Lord that she knew they were on “a battlefield” but that there was “great purpose” in their fight. “We’re expecting you, Father, tonight,” she said. “And I thank you for these two amazing fighters and the team around them. Amen.”

In the greenroom, Bannon was not falling asleep. His eyes were fixed on the feed of Lake onstage. “She’s trying to be senatorial,” he told me, inching closer to the television to study her performance. After Bannon was booted from the Trump White House, he trained his fire on the rest of the world, landing in European countries where the far right was on the rise to counsel the likes of Giorgia Meloni and Alice Weidel. I told Bannon he was the Phil Spector of telegenic women of the far right. “The ‘wall of sound’ has never looked stronger,” he said. He thought Lake could sing, but as she addressed the crowd, he winced.

“Have you gotten riled up?” she asked. “Okay, so then maybe I can bring us into the realm of ‘Let’s get encouraged.’ Because I’ve been riled up for, I feel like, years now, and I’m ready to remember that we’ve got to keep a heart in this.” She was calling the Lord in with love. Bannon guffawed. “Not my style,” he said. “But I love her. And if you look at the polls, she’s doing well.” A man walked into the room and handed Bannon a business card. It was Barry Goldwater Jr., son of the late Arizona senator and godfather of a kind of conservatism the Republican Party hasn’t expressed familiarity with in a long time. A few minutes later, Mike “the MyPillow Guy” Lindell popped by to say hello. That was more like it. Lindell was a better representative of the Republican Party now: the nightmare outfitter kingpin, an infomercial superstar, crucifix dangling from the collar of his shirt. Bannon nodded as he spoke, but he was looking past his shoulder to the screen. “This is trying to humanize her,” Bannon said. “She’s trying to talk to an audience outside of here.” It was not clear what type of voter outside the MAGA base might be tuning in to such a niche spectacle. One of Lake’s aides, sensing Bannon’s disapproval, tried to smooth things over. Lake had changed her speech that morning and didn’t tell anyone, the aide said. “Are you gonna fire the speechwriter?” Bannon asked. “Oh yeah,” the aide said.

As Lake wrapped, Bannon booked it to the stage. He climbed the stairs and stood behind the screens. Fog rolled through the corridor, engulfing everything in its path. In this cloud of vapor, Bannon appeared, finally, like the man of mystery he had played in the media for so long. The producer gave him his cue. The screens parted. Flames shot out of the floor. He never did write a speech. Not really. But if you were listening from the auditorium, you couldn’t tell. He told the crowd about the globalists and the “fat cats” at the Republican National Committee and “Judas Pence.” They chanted and hollered in response, thrilled by the sight of their prince of darkness. He timed his remarks perfectly, ending with 15 seconds left on the clock. And, well, that’s showbiz, baby.

The border itself has always been about stagecraft too.

In 1888, U.S. Department of Agriculture investigators began researching the curious case of the dying cows. As herds from cattle drives in southern Texas made their way north to Kansas, hundreds of animals became sick and died from what ranchers were calling “Texas fever.” The government determined the culprit was extreme anemia caused by red-blood-cell-destroying Babesia parasites transmitted by two specific ticks, invasive pests brought to the Americas by European colonists. The disease was an existential threat for the cows and for the industry, already a major part of the U.S. economy, built around their exploitation and slaughter. The USDA hatched a plan to heal them both: Officials would follow the path of the herds in reverse, north to south, and kill the ticks farm by farm, cow by cow, dipping the animals into arsenic baths. By 1906, they made it to the border, a place then loosely defined and hardly patrolled by lawmen known as Mounted Guards concerned mostly with migrants from China (the only nationality legally prohibited from moving across America’s borders prior to World War I). There, the USDA set up quarantine checkpoints to screen cattle for disease.

But the department’s vertical eradication strategy had left some American ranchers with the impression that the problem was unsanitary cattle from the south infecting pristine cattle from the north. The American ranchers took offense when their cows, having wandered across the border, were required to quarantine upon reentry. They “created a powerful discourse about race at the border,” according to historian Mary Mendoza, “even if humans were not those being racialized.” In response to their outrage, the Bureau of Animal Industry constructed a fence in Otay Mesa, in southeastern San Diego, to prevent cows from rambling into the wrong country. Completed in 1911, the four strands of barbed wire were the first federally funded barrier at the southern border — installed not to keep Mexican people out but to keep American assets and anxieties in.

Fences were a practical matter and a powerful image, springing up here and there, built by the countries on either side of the divide. Official American immigration policy evolved to reflect the fear of the day — booze during Prohibition, Axis saboteurs during World War II, Communists during the Red Scare, overpopulation during the 1970s, marijuana during the War on Drugs — while American foreign policy determined whether the border was a stage for crime fighting or warfare. In 1994, NAFTA rendered the U.S. economy borderless, while the crime bill pledged $3 billion to enhance border policing, track immigrants’ legal status, expedite deportations, and fund migrant incarcerations. As the number of Border Patrol agents grew into the tens of thousands amid the War on Terror and the area they patrolled sprawled into an ever-larger desert expanse, the border itself — the actual physical boundary — was rarely an object of partisan political debate.

Senators Joe Biden, Barack Obama, and Hillary Clinton voted to approve the construction of 700 miles of fencing in 2006. Comprehensive immigration reform remained an elusive goal for both parties, but the ideological disagreements that killed bipartisan negotiations time and again were about the interior of the country, not the line that determined where its exterior began. The conservative right routinely denounced these proposals as “amnesty,” the labor left as wage suppression for American workers.

Meanwhile, Republicans were losing the popular vote in presidential elections, and party leadership increasingly thought messaging on immigration was to blame. Mitt Romney said undocumented immigrants should “self-deport,” and after his 2012 defeat, the RNC concluded that the future of the party would depend on its ability to “carefully craft a tone that takes into consideration the unique perspective of the Hispanic community.”

The modern border crisis arrived two years later, in 2014, when migrants fleeing violence and poverty in Central America began crossing the Rio Grande in record numbers, sometimes more than 4,000 a day. The Obama administration, which would deport more undocumented immigrants than any in history, called in backup for an overwhelmed Border Patrol and constructed a new processing center, where detainees were separated by metal fencing, young men in one area, mothers and small children in another, families in another. Migrants called it the dog kennel, la perrera. It was condemned by the likes of Breitbart.

Then, on June 16, 2015, Trump rode the escalator into the atrium of his Fifth Avenue high-rise to announce that he was running for president because the American people were getting ripped off by their leaders and the country was less safe and less prosperous as a result. “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re not sending you. They’re not sending you. They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists,” he said. It wasn’t just Mexico, he added. It was “South and Latin America,” and “probably” it was “the Middle East,” too. But it was Mexico that he promised to address first and most forcefully. And it was the wall itself that he identified as the symbol of American security and wealth, his very own Lady Liberty in reverse. “So just to sum up, I would do various things very quickly,” he said. “I would build a great wall, and nobody builds walls better than me, believe me, and I’ll build them very inexpensively. I will build a great, great wall on our southern border, and I will have Mexico pay for that wall.” The Trump era of American politics had begun, and the very concept of border security was claimed as an extension of the Trump brand. It always came back to real estate.

Kari Lake for Senate is headquartered on the first floor of an office complex in the shadow of Camelback Mountain. When I visited in February, I was led to a small sunless room where two dining chairs had been arranged to face each other a few inches apart beneath a large professional light stationed nearby, angled to cast the candidate in a fuzzy yellow glow. The bigger the light, the softer the lighting. That’s the kind of lesson you internalize after 30 years in front of the camera, which is how long Lake was in local TV news before she abandoned the trade for politics. The Kari Halo — Vaseline-on-the-lens meets your standard-issue baby-face filter — has become an identifiable feature of Lake’s persona, as the Hair once was for the Donald.

As I absorbed the oddness of the staging, a camera hovered over my shoulder. It was operated by Jeff Halperin, Lake’s husband and cinematographer. Anywhere Lake goes where she may encounter the press, Halperin is rolling, prepared to capture any exchange between his wife and the media that might make good content for her branding exercise. It’s essential to Lake’s success to be able to present herself as a victim of the same Media Establishment–Deep State conspiracy that has victimized the former president. (It was in this spirit, in January, that Lake published a recording of the chairman of the Arizona GOP offering her a bribe to exit the Senate race, prompting him to resign.)

If you want to speak to Lake, you have no choice but to participate and, really, no good argument against participating. After all, if you’re recording the interview, why can’t she? Lake described the deal to the Washington Post this way: If the campaign feels the press has misrepresented her, it will release the footage. If it “goes great,” it won’t. The camera renders all parties performers through its promise of a Mutually Assured Viral Moment. Together, you are at risk of making campaign reality television with Lake billed as star and executive producer of the production. It goes without saying that she gets final cut.

Lake grew up in Iowa, the youngest of nine, and made it out of there fast, landing a job as a production assistant at a local TV station, where she worked for a few months before taking her rightful place in front of the camera, doing the weather in Rock Island, Illinois. Succeeding in TV news requires ambition and shrewdness. With her pixie cut, pleasing face, and no-nonsense yet still feminine vibe, Lake rose to the top of the Phoenix media market as it became the 12th largest in the country. She was not especially political. She practiced yoga and took an interest in Buddhism. Put off by Republican foreign policy, she changed her party affiliation to Democratic after Obama’s election. (Halperin donated to the Obama campaign, according to Federal Election Commission filings.) Then she switched it back, and by the time Trump was running, Lake was publicly expressing her sympathy in what turned out to be the beginning of the end of her media career.

She was, in other words, the kind of swing voter who may decide the 2024 election in which she is running. Still, it wasn’t until the coronavirus pandemic that she says she began to feel the news was fake. “We’ve got a government shutting us down, masking our children, forcing us to get shots against our will. We have a government shutting our businesses down, yet the big multinational corporations get to stay open … At the same time, we’ve got riots happening on the street, businesses are being torched, cop cars are being turned over, antifa is throwing bricks at people’s heads. And the media was calling it peaceful protesting,” she told me. “I just was saying to myself, This is so backward, this is so wrong. As journalists, we’re supposed to question and push back against our government. And no one is doing that.”

The problem with Washington, Lake said, was that people arrived there only to be “absorbed by this disgusting, moldy sponge that takes you in and never lets you go.” She was an outsider, just like Trump, she said. “And I think that’s why they’re intimidated by me and why they hate Donald Trump.” This was true for the media, too. “I think that’s why the media hates him as well,” she said. Hate? Talking to Lake feels like performing open-heart surgery on a balloon animal. It’s an impossible and unnatural enterprise. Lake is intent on ensnaring her interrogators, and even if you refuse to be baited into argument and speak with care so as not to generate for her a new meme about media bias or general badness, she nevertheless succeeds in forcing you into the story of Kari Lake.

I was actively conscious of this when I questioned whether it was true that the media hates Trump. The relationship felt much more complicated to me. Toxic and symbiotic. Depending on your bias, the media was the host and Trump was the parasite, or Trump was the host and the media was the parasite. Lake was prepared for precisely a moment like this. “Well, do you hate him?” she asked. She reached over to a stack of papers on the table to her right.

“Is that my archive of mean things I’ve said about Donald Trump?” I asked. She struck a disappointed-in-me tone.

“You wrote this story? You wrote this horrible story,” she said. She had printed out 8,000 words I had written about my most recent interview with the former president at the beginning of this campaign. “It’s just nasty,” she said. “I got halfway through, and I said, This is terrible.” She didn’t approve of using anonymous sources, she said, and she didn’t use them herself as a journalist unless they were thoroughly vetted by her network. “I challenge you to sit down and read that,” she said. “Well, I wrote it,” I said. “As a matter of fact,” Lake continued, “I almost canceled the interview. I said, ‘I don’t want to deal with somebody who writes like that because it’s just going to be a hit piece.’ But we’ll see how this turns out. The great thing is we have it recorded.”

I mentioned that I would be interviewing Gallego the next day. “I hope you’ll ask him a couple of things,” Lake said. I was expecting some hard questions about the Biden administration. I was not expecting the following, which Lake launched into with her perfect diction and machine-gun delivery: “Why did he walk out on his wife when she was nine months pregnant with his first son? Why’d he leave her for a D.C. lobbyist? Because the people of Arizona actually do want to know why. And if he’s going to do that, then he’ll walk out on us.” I wondered how Lake reconciled her criticisms of Gallego’s personal relationships with her support for Trump, not a model husband but a prolific one. “He didn’t run off on his wife while she was nine months pregnant,” Lake said. Did it matter when he left? “Yeah, it does, actually. He didn’t run off — you don’t know what happened in the divorce! But a divorce is one thing. When you walk out — do you have children?” I don’t, I said. “I didn’t think so,” Lake said, “because you would never have asked that question.” She refers to herself as a “Mama Bear,” a designation that has taken on new importance now that Sinema’s exit has simplified the gender dynamics of the race. “It’s a cleaner contrast,” as one of Lake’s advisers put it. She plans to lean in.

Lake’s case against Gallego is only personal as it relates to his first marriage and his small stature. She refers to him as “Little Ruben,” her very own Trumpy nickname, a callback for the fans to the 2016 Republican primary, when Marco Rubio, the first Florida politician to challenge Trump for the nomination while balancing on block heels, was christened “Little Marco.” (Rubio is now reportedly on Trump’s shortlist — sorry — for vice-president; last month, he told the press it was “an honor” to be considered.) In substance, her argument amounts to the standard generalization of the failures of national liberal public policy. Homelessness, drug addiction, violent crime, and, above all, the mayhem at the border, which she has called a “Biden-vasion”: That’s on Gallego as much as it’s on Biden, according to Lake. “Why did he say that walls don’t work when we know they do?” she asked. “Why did he vote against the border wall? Why did he always vote against President Trump when President Trump was trying to secure our border?”

In Lake’s telling, life was much better four years ago, and that was because of Donald Trump, and a vote for Kari Lake is a vote to give Donald Trump the freedom to govern in the most Donald Trump way possible. The same was true for the border. “The problem is easy to solve. It can be solved in a week or less,” she said. A week or less to fix the most complex domestic humanitarian crisis of the century? “Yeah, go back to President Trump’s policies, and it can be done in a week. For the most part. We’ll have that solved in a week.”

But there is a complication at the heart of Lake’s campaign. Trump supporters love her because she refused to concede that Trump had lost in 2020 or that she had lost in 2022. She had waged legal warfare over what she insisted was a rigged election. When she lost in court, she filed appeals. Soon, she would file a new one in the Supreme Court. She dismissed the audits that concluded there had not been meaningful irregularities in Arizona’s vote totals (and that, in fact, Biden’s victory had been undercounted by several hundred votes). Now, she needed the very people who believed her to believe that it was going to be different this time, that their votes would be counted, that the forces that kept her and Trump from power last time would just accept these results, though she couldn’t articulate why.

Trump had encountered similar difficulties on the trail. In Michigan in the fall, I watched as he stumbled over his words, unable to decide if he was technically the president right then or if he lived in the consensus reality where Biden was president. “And in my second term — which we’re sort of having now …” he said, sounding as if he had confused himself. “But I don’t want the results of this second term. This second term is a disaster … But in my second term, we’ll finish the job and we’ll get rid of the cheaters, the liars, the scammers, and the criminals.”

I asked Lake how she could ask voters who believe the elections were stolen from her and from Trump to bother voting this time. “We’re working really hard,” she said. “I don’t think it’ll be perfect by any means. But we’re working really hard to make sure that we get reform in our elections so that people feel confident in them, that we know that every legal vote is counted, and that when people show up to vote on Election Day that the polling places actually are functioning, the printers are working.” The more I asked about the claims of a rigged election, the less she wanted to discuss them. “Well, I could go into a lot of detail,” she said, “but I’m not going to because what happens is the media will say, ‘All she talks about is rigged elections!’ ”

Lake would also need to find a way to appeal to voters who might be scared off by her appeal to Trump voters — the swing voters in the suburbs who might have been inclined to support Sinema but might be reluctant to back a candidate dying on the hill of election fraud. When Arizona swung for Democrats in 2020 for the first time since 1996, the professionals who analyze events they could not predict credited the shifting Sun Belt demographics and, less scientifically, middle-class aversion to Trump’s yearslong crusade against McCain, a war hero and the senior senator from Arizona until his 2018 death from brain cancer. “If Kari works as hard for the Republican Establishment vote as she did for America First, she can close this deal,” Bannon said, but Kari 2.0 isn’t working on everyone. Lake had bragged about how she “drove a stake through the heart of the McCain machine” in Arizona and had told McCain Republicans to “get the hell out” of her events. Recently, she extended an olive branch (but no apology) to Meghan McCain. The response? “No peace bitch.”

As Lake spoke, I found myself thinking of Jessica Simpson, who wrote in her memoir that, as her relationship with Nick Lachey fell apart, the only time they would speak was when they were filming Newlyweds, their MTV reality show about a beautiful young married couple played by Jessica Simpson and Nick Lachey. The unanswerable question, the one that hangs near the big light and the roving camera over any interaction with Lake, is this: Is she for real? It’s tempting to imagine the Lake production (in fact a production of ZenVideo, Halperin’s company) as a kind of Truman Show in which Lake has cast herself as Tracy Flick in a reality somewhere between Westworld and Stepford.

At a certain point, I announced that I was shutting off my recorder and that I wanted to talk off the record. I intended this as an invitation for Lake to yell “cut.” To stop acting. To exhale. She didn’t. Halperin kept rolling as Lake showed me the encouraging letters she had received from supporters and as she gave me a KARI LAKE FOR ARIZONA shirt and walked me out to the lobby.

At an event soon after, in Yavapai County, Bannon helped Lake solve the rhetorical rigged-election riddle: “Outvote the fraud.” That’s what he told the crowd they would need to do come November. Clever, concise. People clapped. Lake looked relieved. Then a woman in the crowd grabbed the mic to ask a question. She explained that she is a psychotherapist. Bannon asked if he could give her Trump’s number, and everybody laughed. It’s not that people don’t think he’s crazy. It’s that they rather like that about him. He is crazy on their behalf.

The day after my interview with Lake, Gallego was sitting at his regular table at El Mesquite Cocina Mexicana in South Phoenix, deliberating over his choice of carbs. Although no other dietary decision to which I had thus far borne witness suggested this to be the case, he was on a diet, which meant that even though he really wanted flour tortillas, he would have to survive with corn. The flour-versus-corn theory of weight management was gospel among Hispanics, he said, and to prove his point, he asked the waitress for a second opinion. “¿Puedo comer tortillas de trigo si estoy tratando de perder peso?” She shook her head: “No, las tortillas de trigo engordan. Puedes comer tortillas de maíz.” If he wanted to lose weight, he would need to make some compromises. He took her advice with sober resignation, as though it came directly from Peter Attia.

Gallego is the ideal representative for the Democratic Party in Arizona in 2024. A transplant to the state, young, Hispanic, progressive but not woke, with working-class roots and military service and an Ivy League degree. He reflects the demographic shifts political scientists talk about when they talk about voting trends in the Sun Belt. For voters who say they want a return to normalcy, there may be some appeal in a slow burn, in the kind of public figure whose most well known media appearance was when he told Bill Maher it was idiotic for his party to refer to Latinos as “Latinx.” (Lake would prefer that voters remember his second-most-semi-viral moment, when he tweeted at a fellow Marine to “shut the fuck up” and get vaccinated; he tweets a lot.) The Gallego campaign is about reason. As in Ruben Gallego is a reasonable person and Kari Lake is not.

“I always thought she was perfectly nice,” Gallego said. “I would say she was a very professional reporter, and I always treated her professionally. Really, this whole change happened three years ago. It just came out of nowhere. And now it’s like every day it’s something different, some different attack.” He wasn’t surprised by what she had to say about his first marriage, exactly, but it was strange and complicated, the kind of collaterally damaging thing that deters people from seeking office in the first place. “Kate and I are friends,” he said, referring to his first wife, who is the mayor of Phoenix and who has endorsed his campaign. “She’s always had my back, and I’ve had hers. We’re raising a beautiful son together.” He tried to shrug it off. (The Washington Free Beacon, a neoconservative online publication, is suing to make his divorce records public.) “‘Mama Bears’ don’t attack democracy by being election deniers,” he said. “‘Mama Bears’ don’t back up January 6 rioters. She wants to use that term, but she actually is very dangerous. Very dangerous for democracy.”

Danger is an accusation lobbed by both candidates. On day one of his presidency, Biden sent Congress a bill that promised a pathway to citizenship for 11 million undocumented immigrants and took executive action to pause deportations and stop the construction of Trump’s border wall, kicking off years of conflict over policing, detention, and funding with state and local officials, from Greg Abbott, the Republican governor of Texas who has sought to militarize his border and sent busloads of migrants to sanctuary cities, to Eric Adams, the Democratic mayor of New York City who has received busloads of those migrants — more than 170,000 — and begged the administration, without success, for federal relief.

High-profile incidents of crime committed by undocumented immigrants have become important data points for the Trump campaign, anecdotal proof that, whatever the statistics say, Biden’s America is less safe. Soon, Laken Riley, a 22-year-old student in Georgia, would be murdered while out for a run, and an undocumented immigrant would be charged with the crime. Republicans seized on the event. Lake recorded a response to the president’s State of the Union address while wearing a T-shirt, printed in the style of her campaign merch, that read LAKEN RILEY. “We have to protect America’s women, and that begins by ending Joe Biden’s border crisis, kicking him out of office, and removing the Biden yes-men, like my opponent, Ruben Gallego, who have allowed these tragedies to transpire,” she said.

Gallego shrugged at Lake’s opportunism. Although public polling confirms that Arizona voters care more about border security than any other issue, with the economy a close second, it’s Gallego’s opinion that Lake fixates on the border with a national audience in mind. “It’s easy to demonize things that come from Mexico,” he said. “If you turn on the TV in Arizona, they’re not talking about the border every day.” He believed — had to believe, really — that most people are capable of appreciating the nuances of the border issue and immigration. He had to believe that most people are reasonable. That they can see through Lake’s act.

His challenge is to let Lake exist as an extension of Trump — and to encourage voters to resist her attempts, halfhearted at best, to strike a softer, more senatorial tone. So far, circumstances are favorable. In March, the Justice Department announced that 20 individuals had been charged in connection to threats made against Arizona election officials, including threats against the Democratic governor, Katie Hobbs, whom Lake insists she beat in 2022, going so far as to call herself the state’s “lawful governor.” Gallego laughed off Kari 2.0. “For somebody who wants to be moderate, she does a lot of things that are not wise, you know? She’s having a fundraiser with Roseanne Barr and some other crazy guy down at Mar-a-Lago.” (The other hosts of the event, on April 3, were right-wing comedians Chad Prather and Jim Breuer.) “I personally don’t think Arizona’s where she is,” he said. “I think a campaign that’s a little more happy-go-lucky and focused on people instead of whatever she’s into now is going to win more than anything else.”

Back at the border in Yuma County the following day, the vibe was righteous, the displays religious. In the lot behind Britain’s Farm Chuckwagon & Steakhouse, a crucifixion had been staged in the bed of a pickup truck. Someone had carved the face off Jesus and replaced it with a mirror above a sign that read BECAUSE NOBODY TRULY UNDERSTANDS UNTIL IT’S THEM. A DJ, wearing an American-flag-patterned blazer, spun a pop song that went like this: “Trump won and you know it! / The fake news will never show it! / Trump won and you know it!”

Johnathon Alexander of Live Border News stepped onto the platform to speak. “You got the No. 1 human trafficking in the world. No. 1 drug trafficking,” he said. “We got enough fentanyl coming through our border right there each and every day to kill every last man, woman, and child here in America.” Someone shouted that killing Americans was the point. “You’re right. That is their goal,” Alexander said. “You see little 4-year-olds coming through that border that smell of semen, that have been brutally raped by the cartel. They’re evil thugs. As far as I’m concerned, they need to be removed from the planet.” When Trump gets back in office, he added, “he will launch a full-scale invasion on the cartel and knock those little bastards right out of the park.”

This was the Republican border gothic, a welcome party for the Take Our Country Back trucker convoy, a traveling protest against illegal immigration. A few days earlier, thousands of truckers were said to have started their journey from Virginia Beach, rolling through Florida, Alabama, Louisiana, and Texas on their way here, where they would rally in opposition to the failure of the Biden administration. And it was true that it was a failure, even if it wasn’t unique to the current president and even if the far right exaggerated circumstances in depraved detail. Biden won while promising to reverse Trump’s draconian efforts to discourage the arrival of asylum seekers and make examples out of those who arrived here anyway, and the result was the worsening of a humanitarian crisis that was already at a biblical scale. On a single day, U.S. Customs and Border Patrol may now report more than 10,000 encounters with undocumented migrants. In a month, more than 250,000. And those are just the people they see. It’s more people than the entire population of Scottsdale, Glendale, Peoria, or Tempe. More people than officials know how to process or what to do with. By February, Biden was reportedly looking into an executive action to shut the border down.

I lingered near a float made of plywood and red, white, and blue tinsel. A group of elderly people sat on folding chairs nearby, and we got to talking. Gary wore a tan windbreaker and big dark sunglasses that made him look like a fly. He flashed a grim smile. He had a question, he said. He wanted me to tell him what Joe Biden had ever done for the country. I dunno, I said, but he would probably say something about infrastructure. That wasn’t what Gary wanted. Gary wanted to know what I would say Joe Biden had ever done for the country. Could I name a single thing? It’s a trap to engage in political debate in a place like this, to serve as representative of the liberal media. I hadn’t ever thought about it, I said.

Gary’s float was decorated with signs that read MARK LAMB FOR SENATE. Lamb is the sheriff of Pinal County and a declared candidate in the Senate race, albeit one with no real campaign. While Lake’s trail cuts through the kinds of towns with luxury spas and art galleries and lots of white women sporting turquoise jewelry, Lamb’s presence is felt most on the border, where Lake hadn’t been since her Mama Bear Border Tour back in November. The border is most useful in theory. As Gary saw it, Lake was still a reporter, and by that he meant she was calculating and untrustworthy. As proof, he offered her stunt with the Arizona GOP. He didn’t much care that she had exposed corruption. He just thought it was indecent to have recorded a private exchange and even more indecent to have made that recording public. The exposé had really exposed Kari Lake, as far as Gary was concerned, and he didn’t like what he saw.

Gary waved over a younger man in a red polo shirt who, upon learning that someone from the press had bothered to show up, placed a call. A small man ambled over to the float in a cowboy hat. Red polo shirt introduced him. They were ready for their interview now, they said. I had not asked for one. We all stepped up onto the float. The trio sat down on the benches. They told me they were the whistleblowers, the ones from the Dinesh D’Souza film 2000 Mules. The votes had been stolen from Donald Trump, they said. They had proved it.

It was around this time that I began to wonder where the truckers were. Per the schedule, the convoy would arrive in two parts. The first was set to roll through at 3 p.m. and the second at 6 p.m. But something fishy was going on. The convoy organizers had sent out a warning that no trucks should stop in Eagle Pass, a Texas town on the Rio Grande, because it was a setup. It was January 6 on wheels. “Federal infiltrators are waiting there. Spread the word! Don’t show up in Eagle Pass! It’s a trap.” I’d first traveled to Eagle Pass two years ago, when a Texas National Guardsman died while wading into the river to save two drowning migrants. He was 22. Now, it was 4:30 p.m. in Yuma County and still no truckers. Just some pickups and sedans and SUVs and minivans and four-wheelers and motorcycles parked all along the narrow street, the venue on one side, standing alone, and farmland on the other. The verdant fields, the clear blue sky. Rumors circulated in the crowd about where the truckers might be. One hundred twenty miles out, someone heard. Two hundred miles. Fifty-eight very specific miles.

I waited, wandering along the road, where demonstrators had planted a nylon forest with dozens of flags staked into the dirt. DON’T TREAD ON ME, the Playboy logo, ALL ABOARD THE TRUMP TRAIN, the Monster Energy logo, FUCK BIDEN, PROUD AMERICAN CHRISTIAN, the Confederate battle flag, DONALD TRUMP: MAKING AMERICA GREAT AGAIN!, and JOE AND THE HO GOTTA GO. The American flags had been bastardized in violation of federal code to feature Trump’s face or slogans about the virtues of law enforcement or some combination of Trump’s face and Christ on the Cross. By 7 p.m., people were leaving, packing their flags and folding chairs into their trunks. The remaining crowd of optimists moved from the lot behind the restaurant to line the street in anticipation of the convoy’s arrival. I waited a while longer. Still no truckers. Darkness fell, a moonless night. A man wore a shirt printed with Trump’s mug shot. It said NEVER SURRENDER! The truckers never showed.