Ruy Teixeira was once known as a Democratic oracle, but these days he’s more of an apostate. In 2002, Teixeira and John B. Judis published The Emerging Democratic Majority, a hugely influential book that theorized Democrats had the potential to ride America’s changing demographics to electoral dominance — if they could hang onto what then seemed like a reasonable slice of their traditional working-class constituency. Barack Obama’s two election victories seemed to bear this thesis out, but it fell apart when Donald Trump harnessed enormous white working-class support to capture the presidency in 2016. That election proved to be a turning point, since which Democrats have morphed into a party whose base comprises college-educated white voters and a solid but slowly eroding majority of Black and Hispanic voters, while Republicans dominate among the largely small-town white voters that swung so hard for Trump.

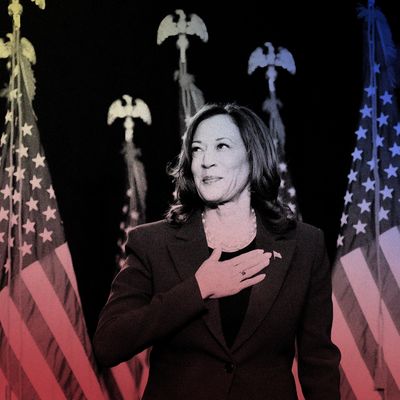

In recent years, Teixeira has taken Democrats to task for, in his telling, alienating these voters by speaking a cultural language anathema to them. He has laid out his critique in many articles and in his most recent book, 2023’s Where Have All the Democrats Gone? (again co-written with Judis). For almost 20 years, Teixeira was associated with the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank; his move to the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute in 2022 underlined his disillusionment with the cultural left. I spoke with Teixeira about how Kamala Harris’s presumptive nomination might shake up the party’s coalitions, whether her move to the center is enough to win over disaffected white and non-white voters, and which of her vice-presidential picks makes the most sense for working-class appeal.

You wrote a piece the other day that pushed back on the idea that Kamala Harris is reassembling the Obama coalition. But she is certainly doing considerably better than Biden was in polling just a couple of weeks ago. Would the loss of working-class voters among Harris voters matter if there are offsetting gains among college-educated voters? In other words, does the composition of her coalition matter so much?

If you gain among group A and those gains balance out your losses among group B, then it’s a net benefit. The question is always “What is the net?” I’m just trying to point out how different the Obama coalition was, and how relatively high the support rates were among working-class voters in general, including both whites and non-whites — that Obama’s coalition was much less dependent on white college-educated voters. It was just a different look.

Things weren’t as class-polarized under Obama as they are now. The Republican and Democratic coalitions haven’t exactly traded places, but they have certainly changed in some important ways. So what Harris is doing right now shouldn’t be confused with reassembling the Obama coalition. Really, what she’s been able to do at this point is push back against some of the losses that Biden was experiencing in his 2024 coalition, relative to the Biden 2020 coalition. In other words, Harris, with her recent success, is getting a little bit closer to where the Biden coalition was in 2020, but that in and of itself is quite different from the Obama coalition.

You’re talking about young and Black and Hispanic voters that she seems to be winning back to some degree, which had been Biden’s big weakness in polling relative to his 2020 results.

It’s a little hard to tell exactly where the gains are coming from, but certainly I think what we’re seeing is that she’s doing a bit better among younger voters, a bit better among Hispanic voters, a little bit better among Black voters, but not necessarily much better among working-class voters. And it appears like she might actually be doing worse among white working-class voters. So that’s the nature of the beast at this point. How all that nets out in terms of building a coalition that can actually win is yet to be determined. Right now it seems to have brought her close to something like parity, but parity is not what you need. As Nate Silver has observed, you need about a two-and-a-half-point national popular-vote margin to actually be favored within the Electoral College, given the biases attended upon the Electoral College today.

She’s not there yet, but she’s getting there, and the question is, where is she going to make further gains? The thing that would bulletproof her coalition would be to bring those working-class numbers in general back at least closer to where they were under Biden in 2020, even if they won’t get to the Obama coalition level. In other words, to try to reduce some of the class polarization in her coalition. And also, critically, she’s got to stop the bleeding among white working-class voters in particular. Because if she does significantly worse than Biden did among these voters, that’s going to filter down to a lot of the key states she needs to carry. If you lose white working-class voters by ten points more in a state like Wisconsin or Pennsylvania, that’s a big hill to climb.

There’s a lot of talk about the white working class, less about the Black and Hispanic working class. We know Harris is winning back some Black and Hispanic voters, but do you have any sense of how that breaks out in terms of education level and how she’s doing among that populace, or is that impossible to tell right now?

We really don’t know. But certainly if you look at where the non-white working-class share is in the Times poll — one of the few people to break it out — she’s clearly doing better than some of the recent Biden results. On the other hand, she’s still 20 points below where Biden was in 2020. So just because she’s making progress doesn’t mean she’s getting to where she needs to be. If she’s increasing the margin she has among Black and Hispanic voters, it would be unusual if she weren’t at least making some progress among the working-class component of those two groups, especially when they’re heavily working class.

It still could be the case that she’s making more progress among college-educated and working-class Blacks and Hispanics. That’s certainly possible. But one thing that people really don’t pay enough attention to, and it’s really important and interesting, is how class polarization has now come to Black and Hispanic voters. That didn’t used to be the case. As I pointed out in my article, if you go back to 2012, Obama does better among non-white working-class voters than the college-educated. Now it’s the reverse. So that’s important. And there was some Pew data that was released before Biden dropped out, which showed pretty big differences between Black and Hispanic working-class and Black and Hispanic college-educated voters. So I think that’s totally something to keep an eye on. Again, we don’t know. The energy and excitement about the Harris campaign is really somewhat skewed toward the more educated, engaged parts of those populations.

Yeah, there’s been a lot of speculation that the class polarization that happened among white voters is just happening on a delayed schedule among everyone else.

Exactly. No question something like that is happening. One thing people don’t think about is that in 2020, racial polarization went down. Even though people were talking more about race at the time and seemed obsessed with it, the fact of the matter is it was somewhat less a driver of behavior in that election than it had been in previous elections, and we may see even less racial polarization in this election.

You’ve been saying for years that Democrats have failed to stanch losses among working-class voters, especially the white working class, because they’ve moved so far left culturally. And I saw that in your recent piece you cited those identity-based Zoom calls — White Dudes for Harris and so forth — that took place recently. I thought they were strange myself. But the Harris campaign wasn’t behind those calls, and it seems to me that she’s making a very conscious effort to move to the center on key issues. She’s disavowed her 2020 positions on fracking and immigration and the Green New Deal, for instance. What do you make of her strategy in that regard?

Well, I think she has to do that. I mean, it just makes Politics 101 sense. She knows, or the people around her know, that these positions aren’t popular and that in particular, with some of the more persuadable, less woke voters, she has to reach, these things are not necessarily deal-breakers, but definitely a negative push on their interest in voting for Harris. So she’s doing the logical thing. She’s saying, “Hey, I’m not for any of that stuff anymore.” Of course, given the part of the campaign we’re in now, this is pretty easy to do, because she’s not being questioned by anybody. Like, “Okay, you changed your position, why is that?” Or, “Now that you’ve changed your position, what is your position? If you’re not for the Green New Deal, what is your position on how far we should go? If you’re not for open borders or not criminalizing border crossings, what is your position? Is it just that, gosh, ‘I wish we’d signed that bill and I will sign it if it ever shows up?’ Are you interested in being tough on the border? What’s your position on crime? What’s your position on equity?” She’s not being asked any questions. She just has a free field to just say, “I’m not for this dumb stuff I said before.”

That’s true. Although I feel like all those questions have a pretty logical, moderate answer that could appeal to moderates while not really shedding voters to her left. She could just say, “Well, I do think we should crack down on the border,” or “I’m for fracking now in limited cases,” or whatever it is.

It’s possible, but I think that’s a lot harder to do than what she’s doing.

It’s harder, no question.

There’s a lot of pressure not to do that. I mean, if you were going to say, “Not only would I sign the border bill that was not signed previously, but if it’s not signed, I will do everything in my power to stem illegal immigration and I’m going to actually get rid of some of the criminals who are in the country,” or something like that — sort of back to the Obama-era stance on illegal immigrants in the country — I mean, that would be a signal.

But that’s what Biden has done in the last year, right?

He’s tried to do it. It’s a little bit too little, too late in some sense. But yeah, sure, it’s a logical thing to try to do. But, again, it’s easier to do this in the current phase of the campaign than it will be when it’s more of a give-and-take about, “Why did you say what you said when you said it? What do you say today? What about your responsibility for however many millions of people did come across the border legally, and you were kind of in charge of the border?” I’m interested to see what will happen when there’s no longer free passes about this stuff and she has to negotiate her past positions relative to her current position, to find her current position and basically reply to questions. We’re not there yet, but I think we will get there. But back to your question about what I think Democrats should do culturally, I do think they need to pretty dramatically move to the center in a lot of these things.

And my point was that’s what she’s doing — maybe not on everything.

Well, I wouldn’t call it dramatically moving to the center.

Inching toward the center.

Inching toward the center. Maybe that’s a better way of putting it. I actually think she probably would be well advised to do more and do it more aggressively. But yeah, you’ve got to start somewhere. You can’t argue with that.

You’ve been highly critical of Democrats for their lack of working-class appeal, and yet they have been on an electoral winning streak the last six years. I guess this gets back to my first question. If they didn’t do better with the working class and actually got worse and yet still won elections, would it matter?

Well, that’s an empirical question, right?

But also a cultural one.

If she loses the working class by ten points and it has something to do with the Democrats’ current cultural image, and she still wins the election because she does so much better among the college-educated — I mean, yeah, it could happen, but I doubt it. I think that’s not sustainable and probably not even achievable within this election context. But I think it does raise questions about the kind of party you are and whether you have a sustainable electoral strategy in a closely divided country where we always are having these secret polarized and very close elections. If you’re a Democrat, presumably what you want to do is develop a coalition that could be not only squeaked through, but be pretty dominant for a while so you can accomplish the things you want to accomplish and define a new political era.

I don’t think we’re there yet, and I think that it would be pretty weird if the Democrats managed to pull out an election while doing significantly worse among working-class voters, including non-white working-class voters, and manage to gain just enough college-educated voters in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania to win. It can’t be ruled out. Mathematically, it’s possible. But I think it would be pretty discouraging and weird if it happened, and definitely hard to sustain. The ’22 and ’23 elections were pretty different, in the sense that we know the way the Democrats’ coalition has evolved, they actually do better.

Because it’s made up of high-turnout, educated voters.

That really helped them. I mean, look, they’re running against a party that has all kinds of problems. If the Republicans had run slightly better candidates in 2022, they’d probably control the Senate.The inability of Republicans to field even replacement-level candidates … Trump isn’t even a replacement-level Republican candidate!

Of the VP picks that Harris is considering, which makes the most sense to you?

The de rigueur political-science point is that in the end, vice-presidents don’t matter that much anyway. But this could be a close election. Things will be decided at the margin, maybe at the margin of the working-class vote. So that would tend to point you toward a moderate, quote, unquote, midwestern governor. I think Josh Shapiro would be the logical pick, I really do, because Pennsylvania’s so important because he has a track record of saying and doing moderate things. He’s a good campaigner. I don’t know why not, really.

Yeah, he seems to be the guy if you want to solidify the electoral advantage.

And that’s what the Harris campaign has basically said: “We’re mostly interested in winning.” I’m not a betting man, but if I was, I’d pick Shapiro. But stranger things have happened. I actually don’t think Tim Walz would be that good.

Why is that?

Minnesota’s not that important. And there’s just something about him that seems needlessly … He combines affability with truculence in a way that I think is maybe not ideal, but that could just be me. I think Shapiro has been a more interesting governor. Walz has really governed from the left in Minnesota, if you look at his record. Whereas Shapiro is really consciously trying to steer to the center.

I have to mention The Emerging Democratic Majority, which you’re still probably most famous for. Back in 2002, you predicted that, if I have this right, an alliance of college-educated professionals, minority voters, and single women would lift Democrats to victory in a sustainable way.

Yeah, give them an advantage of time. And it did play out that way in the early Obama coalition years. But we didn’t anticipate a number of things, as we noted in the book. And we always made the point that a certain level of white working-class support was still necessary for some sort of successful Democratic coalition. Maybe 40 percent nationally, maybe closer to 45. But at any rate, they couldn’t afford to lose a lot more support among this demographic, because it was still huge, even if it was declining. So we made that point, but people forgot about it, of course. And it did wind up undermining the Democratic coalition in important ways.

Another thing I think we didn’t anticipate is the ways in which the Democratic Party would, in a sense, become redefined by the domination of college-educated professionals, particularly in certain areas of the country in what we called ideopolises. We didn’t anticipate the extent to which that would take over the party and redefine it, would set priorities for the party and what it stood for. What we called for in the book was progressive centrism, which would take advantage of the ways in which the country was evolving culturally and ideologically, but without going too far in the direction that they wound up going.

By that you mean not just lawmakers, but left-leaning nonprofit groups and other groups.

Yeah, the whole “shadow party” we talk about in the new book. That turned out to be very important, and we didn’t see it coming.

I think the common conventional wisdom says the influence wielded by those groups may have peaked a few years ago — summer 2020, let’s say.

No, I think it’s still enormously powerful. I think there’s been a little bit more looseness in the culture in terms of what you’re allowed to at least talk about. But I think the influence of the shadow party and its basic political stance hasn’t really changed that much. It’s just they’ve learned to keep their head down in certain areas, and they do. They can’t be too crazy if they want to make a plausible case that their kind of politics can win or is important or should be prioritized. But you look at the climate movement and what they stand for. You look at the trans-rights movement and what it stands for. You look at the various racial identity groups that are influential in the party. I think they still really haven’t changed their position. You look at the rise of the Omnicause, right? About how all these things are melded together. If you’re a progressive, if you’re a left Democrat, you not only support X, you support YZ.

Sure, there is that. I just feel the actual party is in a more moderate place. You have, say, the Sunrise Movement, who wouldn’t endorse Biden. These groups are not exactly fringe, and there are important people that back them, but I don’t think they’re as influential in terms of electoral politics as you might be implying. But you’re saying this is more culturally, I think?

Well, culturally, and again, I think in terms of the policy priorities and positions of the party, I don’t think things have changed all that much. The Democrats still aren’t a law-and-order party. They’re still not a tough-on-immigration party. They’re still an all-of-the-above party, consciously, on energy stuff. They’re still, I think, wedded to some fairly left positions that would not have been party positions 15 years ago. And I think it makes it harder to make smart decisions about policy.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.