This story is a collaboration between New York and ProPublica. It was also featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

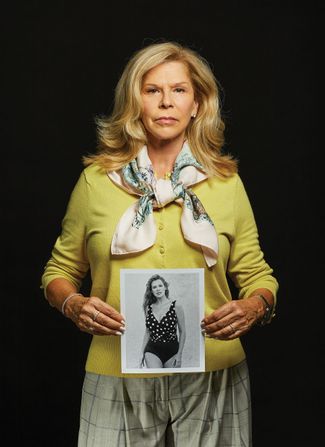

Laurie Kanyok was 38, a professional dancer on the cusp of retirement, when she learned she was pregnant. She had already suffered one miscarriage and had recently undergone a spinal treatment that she feared would increase the risk of birth defects. Kanyok booked an appointment with an obstetrician, Dr. Robert Hadden of Columbia University. She felt grateful to be in the care of someone who had spent his entire career at such a distinguished institution.

At first, Kanyok liked Hadden, who had a soft-spoken, fatherly way. With his prim, grayish beard and wire-rimmed glasses, he reminded her of a “skinny Santa Claus,” as she later put it. But there was one time when, heels in the stirrups, she thought she felt a flicker of something moist on her vagina. During another appointment, Hadden palpated Kanyok’s cervix with such force that his fingers lifted her from the exam table. She heard him moan.

Kanyok dismissed Hadden’s strange behavior, focusing on her baby. “You put yourself aside at that point, right?” she says. “You want to see a heartbeat. You want to know that the umbilical cord isn’t wrapped around the neck. And then you want to know that you’re going to get to the finish line, deliver, and go home. That’s it.”

Six weeks after giving birth to a daughter, on a Friday in late June 2012, Kanyok returned to Columbia’s suite of offices on East 60th Street for a checkup. She looked idly at her phone as Hadden examined her. He assured her that all looked good, and the nurse chaperoning the exam left the room. Hadden started to follow her out. Then he paused, turned, and told Kanyok that he’d forgotten to check her stitches. He instructed her to lie down again.

Beneath the paper blanket covering her knees, between her legs, the assault this time was unmistakable. Kanyok jolted back and saw Hadden’s face surface, bright red. She froze as he chattered nervously and performed what he told her was a breast exam. She texted her boyfriend. “Dr Hadden just licked my vagina,” she typed. “I’m shaking And freaked out.”

Kanyok’s boyfriend ran to the street and handed $50 to a black-car driver for the short ride to Hadden’s office. He collected Kanyok and called 911 twice, first on the drive back to their apartment and again once they got inside. He struggled to articulate what had just happened. “How do you even verbalize this horrendous act of an OB/GYN from a super-renowned place like Columbia?” he recalls. He told the 911 operator that his girlfriend’s doctor had “touched her orally.”

Soon, Kanyok and her boyfriend buzzed up two NYPD officers. As the police took their statements, Kanyok’s phone rang. It was Hadden. He left a voice-mail, which Kanyok played for the group on speaker.

“Hi, Laurie, it’s Dr. Hadden calling,” he said. “It’s, like, 4:30 on Friday. You know, I just got word that you called the office and you’re upset and you’re calling the police. What — what the heck happened? What’s going on? Please, can we talk? Um. If you can, please, just give the office a call and, you know — or come back and talk face-to-face. I, I, I don’t — I don’t understand. I just know that I just got word from the — first from the secretary and then from our office manager and the nurse. So I’m very upset. I don’t know what’s going on. So please, please, call me back. All right. Take care.”

The officers glanced at each other and then at Kanyok. “Fuck him,” she remembers them saying. “Let’s go get this pig.”

Listen to Hadden’s voice-mail:

Audio: Courtesy of the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York

Hadden was arrested at his office later that Friday. Mary D’Alton, the head of Columbia’s OB/GYN department, went to the clinic when she heard police were on the scene. Meanwhile, a squad car took Kanyok to St. Luke’s hospital for a rape-kit examination, then to meet with a prosecutor. She returned home around 11 p.m. After a long shower, she peeked in at her baby. My daughter’s asleep, she recalls thinking, and I am safe. Everybody is safe.

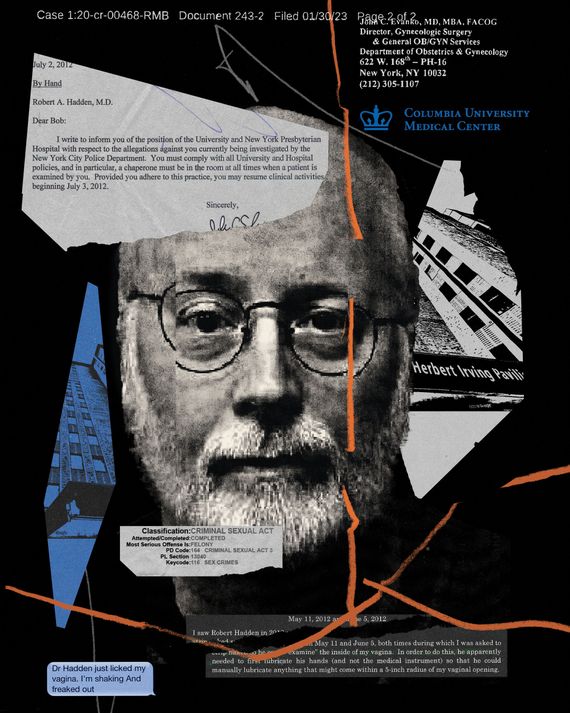

Kanyok didn’t know that Hadden had already been released from custody. On Saturday, police spoke with the department’s administrator, Jeanne Dellicarri. On Monday, Hadden received a hand-delivered letter from Columbia. “Dear Bob,” it began. “I write to inform you of the position of the University and NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital with respect to the allegations against you currently being investigated by the New York City Police Department.” The letter said that if Hadden had a chaperone with him while examining patients, and if he complied with all university and hospital policies, he was free to “resume clinical activities.” The document was signed by Hadden’s immediate supervisor, John Evanko. He cc’d D’Alton; Robert Kelly, then the president of NewYork-Presbyterian, the Columbia-affiliated hospital system in which Hadden was an attending doctor; and Lee Goldman, then the dean of Columbia’s medical school, where Hadden was a member of the faculty. On Tuesday, Hadden was back in the exam room. Columbia let him continue practicing for another five weeks. At least eight of those patients say he assaulted them.

Columbia University — where Robert Hadden spent his entire medical career — has never fully accounted for its role in allowing a predator to operate unchecked for decades. To date, more than 245 patients have alleged that Hadden abused them, which by itself could make him one of the most prolific sexual assailants in New York history. But the total number of victims may be far higher. On any given day during his two decades of practice at Columbia, Hadden saw 25 to 40 patients. Tens of thousands came under his care. A baby girl he delivered grew up to be a teenager he allegedly assaulted.

Hadden, 65, was sentenced in July to 20 years in federal prison — the result of a long, arduous process that Columbia often undermined. One of the country’s most acclaimed private universities was deeply involved in containing, deflecting, and distancing itself from the scandal at every step.

In agreeing to pay $236.5 million to resolve lawsuits brought by 226 of Hadden’s victims, Columbia admitted no fault, which is in keeping with public statements over the years placing the blame for what happened solely on Hadden. But the university’s own records show that women repeatedly tried to warn doctors and staff about Hadden. At least twice, the fact that Hadden’s bosses in the OB/GYN department knew of the women’s concerns was acknowledged in writing. They allowed him to continue practicing.

Once Hadden’s crimes became clear, Columbia worked to tamp down the crisis. It waited months to tell his patients that he was no longer working and then sent matter-of-fact letters that omitted the reason. After police and local prosecutors began to investigate Hadden in 2012, Columbia failed to hand over evidence in its possession despite subpoenas that compelled it to do so. The university also did not tell the district attorney when more patients came forward — witnesses who could have strengthened the case prosecutors were trying to build. The DA found Columbia’s conduct so concerning that the office launched a criminal investigation into the university itself along with the affiliated hospital where Hadden had admitting privileges. The inquiry found that Columbia had, by neglecting to place document-retention holds, “intended to destroy” emails written by Hadden and his former colleagues who had left the university. The DA was able to obtain the records only because they were “inadvertently left on an old server.” (Columbia disputes this.)

The local investigation of Hadden ended in a 2016 deal that allowed him to avoid serving a single day in jail. Cyrus Vance Jr., who was DA at the time, says that if Columbia had fully cooperated, it might have made a difference in his office’s decision to accept a plea. “Obviously, that did not happen,” Vance says. His former deputy Karen Friedman Agnifilo is more direct. Columbia, she says, “didn’t have clean hands here. If they didn’t know, it’s because they chose not to know.” Hadden remained free until his victims began to go public in such numbers that federal investigators took up the case in 2020 and secured his conviction.

In recent decades, several university medical systems have provided cover for abusive doctors whose victim counts run well into the hundreds. Columbia’s failures stand out even in this grim company. Unlike at Michigan State — where Dr. Larry Nassar sexually assaulted young gymnasts — no Columbia administrators are known to have lost their jobs. Unlike at the University of Michigan — where an athletics-department doctor abused mostly male students — Columbia never commissioned an independent investigation into what happened under its roof. Unlike at the University of Southern California — where a staff gynecologist’s abuse led to $1.1 billion in settlements — Columbia’s president, Lee Bollinger, did not resign when the enormity of Hadden’s crimes came to light.

Instead, Bollinger retired on schedule in June, celebrated by a university that continues to uphold itself as a place where eternal virtues are taught and practiced. The announcement of Bollinger’s successor, Minouche Shafik, noted that her most recent book is What We Owe Each Other, “in which she calls for a better social contract to underpin our economic system and challenges institutions and individuals to rethink how we can better support each other to thrive.” Meanwhile, in the Hadden case, Columbia’s pattern of defensive behavior is ongoing. The university still hasn’t informed patients that their former doctor is a convicted sex offender. And Columbia is aggressively fighting new lawsuits from victims, arguing in one case this year that it should not be held liable because Hadden’s actions were “outside the scope of his employment.”

Columbia has long been one of the most powerful and respected institutions in New York. It has a $13 billion endowment, it is one of the city’s largest private landowners, and its board of trustees is stacked with titans of finance and government. But the university declined to make any of its leaders or employees available for interviews. In an emailed statement, an unnamed spokesperson wrote that Columbia was “profoundly sorry for the pain that Robert Hadden’s patients suffered and his exploitation of their trust” before emphasizing that he “purposely worked to evade oversight and engineer situations in which he would abuse his patients.” The statement continued, “We also deeply regret, based on what we know today, that Hadden saw patients for several weeks following his voided arrest in 2012.”

The disconnect between Columbia’s approach and its stated commitment to “the highest standards of ethical conduct” remains inexplicable to many people involved in the Hadden affair, including Friedman Agnifilo. “I’m struggling for words because it’s actually head-scratching,” she says. “They are the best of the best. How could they put someone back the next day after she went to the police? It makes no sense to me. It would be one thing if they just said, ‘You know what? We talked to her — we didn’t believe her.’ But they didn’t even do that.” She is referring to the fact that Columbia’s internal investigation of Kanyok’s allegations failed to interview Kanyok herself.

We attempted to contact more than 100 of Hadden’s former colleagues. Only one doctor, Jennifer Tam, would speak openly. She is no longer practicing medicine. “I would like to think if I was still at Columbia, I would go on the record, but I could see how the threat of repercussions would keep people from speaking,” she says. She recalls being surprised to learn that Hadden had been arrested — and then thinking about how easily any concerns about him could have been rationalized in the workplace she had known. She says there was an ethos at Columbia of keeping quiet about anything that could reflect poorly on the university. “If there was something that wasn’t perfect, you better not talk about it,” she says. “We don’t want to ruin the reputation.”

245 and Counting

Columbia has stymied a full accounting of Robert Hadden’s crimes. Here, 23 of his patients describe their experiences. Portfolio by Hannah Whitaker

There was nothing particularly special about Robert Hadden that would have made Columbia want to protect him. He wasn’t a prominent physician with a roster of elite clients. He wasn’t attracting millions of research dollars or in demand on the academic-lecture circuit. He was one of dozens of OB/GYNs employed by the university and outwardly unremarkable.

Hadden grew up in Garden City, a suburb on Long Island, in an environment that a federal judge later described as traumatic. His family, the judge said, included a mother who had alcoholism and was possibly suicidal, an absentee father, and three siblings with whom Robert “shared a sexual dynamic.” At Skidmore College, in the class of 1980, he tended to shrink into the background. “Somewhat of a phantom,” recalls one of his classmates. Another says it was as if he had a Romulan cloaking device from Star Trek, allowing him to suddenly appear out of nowhere.

Hadden had completed a graduate program in Florida before applying to medical school. Failing to get in anywhere in the U.S., he enrolled instead at St. George’s University in Grenada. He transferred to New York Medical College and, after graduating in 1987, continued his training as a resident physician in obstetrics and gynecology at Columbia.

Then as now, the university played a leading role in a health-care network that was vast and interconnected, from its medical school to Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital to a system of clinics across the city, where doctors in a range of specialties treated thousands of patients. Hadden rose to chief resident of OB/GYN at Columbia’s main hospital campus in 1990 and became a member of the medical-school faculty. Tam, his former colleague, recalls him as someone who was generally quiet, if slightly awkward. Still, she says, he was popular with patients, some of whom traveled from other states because he seemed to offer unusually personal and thorough attention. Hadden’s friendliness also endeared him to his staff. “There was not one person who didn’t love Dr. Hadden,” says Willie Terry, who was then working with Hadden as a medical assistant at Columbia’s clinic in Washington Heights.

One morning, Terry later testified in federal court, she realized she’d forgotten her stethoscope in a room where she had been assisting Hadden. She knocked softly and opened the door. The patient was on the examination table with a sheet over her legs. Terry saw Hadden at the end of the table, one foot on the floor and the other on a step stool. His left hand was pressed against the patient’s knee, holding her leg open, while the other hand moved under the sheet in a way Terry knew was not medical. Hadden’s eyes were shut tight. His face was red and turned toward the ceiling. Terry jumped back and shut the door.

“The man that I saw sent shock waves all over my body,” Terry says. “I said, ‘Dear God, what was that?’” She never reported what she saw. She was certain that her word would have carried little weight against a doctor’s, and she wasn’t the only person who felt that way. A labor-and-delivery nurse who began working for Columbia in the early 1990s later testified that she saw Hadden move his fingers sexually around the labia of women in labor every time he checked for cervical dilation. “I’ve watched porn and I’ve had sex, and it seemed sexual to me,” she said. An attorney pressed her on why she had not blown the whistle. “Historically, there has always been a hierarchy between physicians and nurses, and I felt that I didn’t have a voice,” she said.

Early on, Hadden seemed to target patients who had little context for a normal exam, including women who had never seen an OB/GYN or who were pregnant for the first time — those who did not realize that a breast exam is not required during every prenatal visit and is properly performed one breast at a time, swiftly, using only the pads of the fingers. Those who did not know that a “scoliosis check” or “mole check” while completely undressed is not standard care.

One such patient, a 16-year-old girl from the Bronx, went to see Hadden in 1992. She was five weeks pregnant and had never seen an OB/GYN. She remembers Hadden conducting a lengthy exam that was “very rough,” and he did not stop even when she told him he was hurting her, according to federal court filings. A week later, her boyfriend’s mother brought her back to the clinic to file a complaint. A receptionist gave her a sticky note with a phone number. After calling several times, the girl finally reached a live voice and said that a doctor in the clinic had made her uncomfortable. She was transferred around and left a few voice-mails. “No one seemed to care,” she says. She could never get anyone at Columbia in a position of authority to speak to her directly.

Columbia ignored older women with better resources, too. In 1993, Dian Saderup Monson was living in New York, pursuing her doctorate in American literature, when she became pregnant for the second time. She was looking for an obstetrician closer to her home, and a friend recommended “this newish doctor,” she recalls. “People think he’s very personable. He’s very warm.”

On an October morning, Monson went to her first appointment with Hadden, and they proceeded from a get-to-know-you chat in his office to an exam room. Monson knew immediately that the breast check, prolonged and whole-handed, was not normal; she asked Hadden if he’d felt something concerning. She remembers that during both the breast and pelvic exams, the medical assistant turned her back to face the counter as if she had something to do there. But the counter was empty. As soon as Hadden left the room, Monson felt the assistant’s eyes boring into her. “I felt like she was telling me, ‘Don’t come back,’” Monson says. She did not fully process that she had been sexually assaulted until hours later, sitting alone on her sofa. “It was like a revelation,” she says. “I just suddenly knew. I was just sobbing. I understood what had happened.”

Monson and her husband ruled out calling the police. It would be her word against Hadden’s, and he could discredit her simply by saying that a chaperone had been in the room. But Monson realized that there was one thing she could do. She was a writer. If she created a document for Hadden’s personnel file at Columbia, she thought, more evidence would surely follow. What is their threshold for acting on a complaint against a physician? she remembers thinking. Maybe it’s three people, maybe it’s four, but they’ll reach that threshold pretty quickly. And they will get rid of this doctor.

Still, she dreaded the task and put it off for months. Just a week before her daughter was born, Monson dragged her bulky Hewlett-Packard laptop into her son’s room, sat at his student desk, and typed a letter. She chose impassive clinical language so she would not be dismissed as emotional. “I have never, until being examined by Dr. Hadden, been disturbed by the way a breast or pelvic exam was conducted,” she wrote. She described the sexual ways he touched her in detail. “It is not a pleasant prospect to describe on paper an incident that left me ultimately feeling violated. Despite my long delay in making this complaint, however, I continue to feel that Dr. Hadden’s conduct was improper, indeed, grossly so. I have tried to imagine any of my past or current physicians giving the exam he gave me, and I simply cannot.”

Monson’s husband put two envelopes in the mail. One was addressed to the risk-management department at Columbia, and the second was sent to Dr. Harold Fox, the acting head of the OB/GYN department at Columbia-Presbyterian. The risk office never responded. But Monson received a prompt reply from Fox, who said he would investigate and follow up in two weeks. “I was gratified,” she says. “I was like, ‘Hey, get a load of this!’ to my husband. ‘Can you believe this? They’re actually taking it really seriously.’”

This is the extent of the investigation Fox conducted: He asked the medical assistant whether she had seen anything inappropriate. The assistant said “no,” and Fox let the matter drop. Fox later testified to a grand jury that Sterling Williams, who was then the vice-chairman of the OB/GYN department, had agreed that this effort was adequate. Monson never heard anything from Fox again.

Hadden’s assaults continued. A medical assistant who worked with him at the time recalls questioning, along with her colleagues, why Hadden would often direct them to move on to the next patient before he had completed the exam in progress. Even so, after leaving her position, she returned in 1996 to see Hadden as a patient. She says that as she was lying on the examination table, Hadden rubbed his erect penis on her arm. Stunned and shaken, she told a receptionist that Hadden was a pervert. She recalls that the receptionist replied “I know” and “I’m sorry.”

By 2000, Hadden’s personnel file included a formal write-up for what was vaguely described as “inappropriate use” of a computer. It was signed by Dr. Rogerio Lobo, who was then the head of the OB/GYN department. Within Columbia’s bureaucracy, warning signs both subtle and glaring failed to have any effect. In 2004 or 2005, Katia Herman, a 27-year-old yoga instructor, received a referral to see Hadden from her Columbia obstetrician, Dr. Katarina Eisinger. At their first appointment, Hadden assaulted her, she says. Herman returned to Eisinger for her care and eventually decided to tell her what had happened.

“I said, ‘You know, Dr. Hadden was really inappropriate with me and made me extremely uncomfortable,’” Herman says. “She looked at me. She kind of waved her hand. And she was like, ‘That’s just Dr. Hadden.’” Herman left the appointment feeling like her concerns had been shut down. “I just remember being like, Wait, what the fuck? ” After giving birth, she stopped going to Eisinger and Columbia.

Patients at the Washington Heights hospital where Hadden delivered babies, the Columbia University Irving Medical Center, also tried to complain. Eva Santos Veloz was 18 when Hadden assisted her emergency delivery in 2008. During her 18-hour labor, she recalls, Hadden touched her in ways that made her uncomfortable, sometimes while not wearing gloves. Santos Veloz and her mother complained, but they spoke limited English and couldn’t find anyone who spoke Spanish. After the delivery, they informed a bilingual social worker, who took notes and offered information about postpartum depression. No one ever followed up, Santos Veloz says.

Her mother encouraged her to file another complaint about Hadden with the hospital, but Santos Veloz says she was too scared. Both women were undocumented, and she thought no one would believe them. “For years, honestly, I thought that I was making this up in my head,” she says. “Because at the time that I did try to speak up about it, in the hospital, it was just like, ‘Nothing really happened,’ and I was just overreacting because I was in pain.”

Complaints fell on deaf ears in a myriad of ways. Another former patient, Christina Arethas, tried to tell two of Hadden’s colleagues about him. One was Tam, the sole doctor who agreed to an interview. Arethas recalls saying to her that Hadden was “creepy” and that she did not want him to deliver her baby if he was on call when she went into labor. Tam doesn’t remember the conversation; she is devastated that she could have missed the red flags. “I feel absolutely terrible knowing what we know now,” she says, beginning to cry. She says she might have assumed Arethas simply didn’t care for Hadden’s personality: “I could never imagine that somebody that I practiced with could be doing this behind closed doors.”

Records show that at the time, Columbia had no clear policy for documenting patient complaints or guidance for faculty about how to handle them. In 2007, Columbia circulated a policy requiring chaperones during exams, but several physicians later told the district attorney that they did not recall ever seeing it. In October 2008, another patient made a complaint against Hadden. An administrator named Brenda Cruz sent multiple emails about it and spoke with Evanko. (None of the Columbia personnel mentioned here responded to detailed questions.) He was still Hadden’s boss four years later when he signed the letter authorizing him to immediately return to work after the incident with Laurie Kanyok.

When the NYPD arrested Hadden in June 2012, Columbia acted swiftly to find him a lawyer. That weekend, Helen Cantwell, an attorney representing the university, called Isabelle Kirshner, a prominent defense counselor who had developed what she calls a “niche practice of men behaving badly.” She agreed to represent him. But even Kirshner was puzzled by Columbia’s stance toward Hadden. “I was a little surprised that they let him go back,” she recalls, letting out a chuckle of disbelief. “I have no idea how that came about.”

On Hadden’s first day back at work, he saw a patient who is identified in court as Victim 53. “I was sexually assaulted by a known sexual offender, known by his peers and all levels of hospital management as a sexual predator, literally just 4 days after he was arrested in his medical office and escorted by police out of the building,” she later wrote in a victim-impact statement. “Robert Hadden was actually permitted to RETURN to his medical office and sexually assault me just FOUR days after being arrested for LICKING a patient’s genitals.”

Over the next several weeks, Kanyok asked friends to call Columbia to check if Hadden was still seeing patients. “I used the words prank call, for lack of a better term,” she says. “They told me, ‘I can make an appointment.’ And we would go, ‘Motherfucker …’” In addition to being outraged, she was mystified by Columbia’s passivity — the way it didn’t actually seem to worry about reputational risk: “Wouldn’t you want to cover your ass?”

Columbia suspended Hadden five weeks after his arrest when he would not cooperate with an internal investigation. He took a leave of absence in September, and at the end of the year, the university chose not to renew his appointment. Hadden essentially retired, living at home in New Jersey with his wife, Carol, and their son, who has disabilities. He maintained access to his Columbia email address and used it for years.

The university notified patients that Hadden was gone in a mass mailing in April 2013. “Dear Valued Patient,” the letter began. “We regret to inform you that Dr. Robert Hadden has closed his private practice at Columbia University Medical Center.” The letter offered no explanation. It was signed by Katarina Eisinger, the doctor who Katia Herman says had dismissed her concerns eight years before. She was now the chief of Columbia’s General Obstetrics and Gynecology division.

Meanwhile, the Manhattan district attorney opened an investigation into Hadden. Laura Millendorf, a prosecutor who had grown up in a family of doctors, volunteered to take the case, appalled by Hadden’s profound breaches of trust. “This was horrific enough that it was worth pushing forward as aggressively as possible,” Millendorf says. She suspected that if Kanyok’s story checked out, there would be more victims. “It didn’t make sense to me that somebody — in that position of power, at that age — would graduate immediately to licking the vagina of a patient from never having done it before,” she says.

The key evidence in the case would be Kanyok’s testimony. “She struck me as somebody who would make an excellent witness,” Millendorf says. “She was poised, smart, well spoken, confident, tough. An incredible memory for detail.” But there was a problem. Police records show that while analysis of Kanyok’s rape kit found genetic material from two males — one of whom, naturally, was her boyfriend — the lab could not determine whether the second sample belonged to Hadden. The DA’s office decided to shelve the case. Millendorf called Kanyok to break the news in early 2013. “The main thing I remember is saying I was sorry,” Millendorf says. “That stands out because it was not the culture at that time to say that kind of thing. The expectation was to be ‘Just the facts, ma’am’ — very stiff and almost cold toward your victims.”

Kanyok replied, “Well, what do we do? He can’t practice medicine.” She thought a civil suit might achieve some measure of justice and serve as a warning for other women. One day, pushing her daughter in a stroller through the Columbus Circle mall, she took a call from an attorney she knew: “He goes, ‘You definitely have a case, but you can’t fight Columbia. You can’t. Just be realistic about what you’re doing.’”

Kanyok, along with a friend who had also been a patient and realized she’d been assaulted, sued the university and Hadden anyway in April 2013. A couple of months later, the Daily News published a short item about their lawsuit on the bottom corner of page ten. Some of Hadden’s former patients spotted it and came forward. In July, a longer story appeared, this time with a large photo of Hadden and the headline GYNO IS SICKO.

That morning, a doctoral candidate named Laurie Maldonado boarded a crowded subway car and saw the tabloid. Overcome by panic, she was still fighting to breathe when she left the train. She had been a Hadden patient for nine years, according to civil filings. She recalls that during a dilation check two days before her son was born in 2011, Hadden had examined her cervix with such force that she cried out in agony. “The pain that he inflicted on me was more severe than delivering birth,” she says. “And I gave birth naturally.”

Other women saw the Daily News articles and began to approach the DA’s office. Millendorf phoned Kanyok to say the case was being reopened. “There were numbers now,” Kanyok says. “It wasn’t just me.”

Evelyn Yang was among the new witnesses. She had been seven months pregnant with her first child when, she says, Hadden assaulted her in July 2012, during the window when Columbia allowed him to see patients after his arrest. Yang did not report what happened or even tell her husband. She thought that it must have been a onetime incident that had something to do with her. But she immediately found another doctor to deliver her baby.

Yang did not see Columbia’s “Dear Valued Patient” form letter until she was going through a stack of unopened mail months later. “As soon as I read that, I got goose bumps all over my body,” Yang says. “I could feel all the little hairs stand up. The room started to spin. I remember thinking very clearly, Oh my gosh, could it be that he did this to someone else?” She Googled Hadden and found the Daily News articles. The next thing she put into the search bar was “What to do if you’re assaulted by your doctor.”

Among the results was a legal forum. Most of the posts from attorneys were full of jargon, but one struck Yang as compassionate. It was by Anthony T. DiPietro, a malpractice lawyer who operated a one-person firm in a shared office. Yang, not even sure what she wanted, called and told him her story.

DiPietro believed her instantly. “What woman would go to an OB/GYN for seven months when she was pregnant with her first child and then just have to leave?” he says. Yang wanted to force more information about Hadden into the open. DiPietro arranged for her to give a statement to the DA and filed a civil suit on her behalf, identifying her only as Jane Doe. He held a mini–press conference in his office and posted about the case on his blog in August 2013, writing, “Columbia and NYP Hospital nurses and staff members have information about Hadden which has been kept secret for decades.”

Lawyers for NewYork-Presbyterian (the hospital had been renamed after a merger) objected vigorously, sending a cease-and-desist letter demanding he take down the blog post and issue a retraction. They threatened to sue for libel and to approach the state bar for professional discipline. In court documents, Hadden’s attorneys characterized DiPietro as overzealous, “engaging in hyperbole and distortion,” and said his “true agenda is publicity for himself.” They also accused him of trying to “single-handedly destroy Dr. Hadden and strip him of any of his rights.” Lawyers representing Columbia professed outrage that DiPietro was “using his unknown client to look for ‘victims’ and ‘witnesses.’”

Columbia also embarked on a campaign to force Yang to reveal her identity. In one filing, university lawyers argued that they were in a worse position than she was: “If the alleged offense is so stigmatizing that plaintiff can be allowed to sue anonymously, does it not follow that merely being accused of having committed the act is as stigmatizing or worse? The accusations alone will cause indelible harm to the hospital and university’s reputation.”

As Millendorf pressed the criminal case, she became convinced that Hadden had abused far more patients than the handful who had come forward. “I slowly came to realize that I was dealing with a sexual abuser of epic proportions,” she says. “I was talking to victims and learning of victims and witnesses that went back to the ’90s. I was just doing the math in my head. And I remember thinking, These are only the ones I know about. I was trying to do calculations in my head, like, How many patients does someone see in a day? Even if he abused only 10 percent of them, what are the sheer numbers of victims here? There were victims of all ages and backgrounds — in clinics for people who had no insurance and also fancy offices on the Upper East Side. They were in every office, every age bracket, every ethnic bracket. I remember just being blown away by the numbers. I distinctly remember that when I started to say those numbers out loud, people looked at me like I was crazy.”

The strongest evidence in the case would be the victims’ testimony. “Most of them had some sort of hook, some sort of specific detail that made their story ring true,” Millendorf says. “The way that they knew that he had just put his mouth on their vagina, the way that they knew that it was a tongue they were feeling. These were awkward things to discuss, difficult things to discuss. But they were all really good at it.” By June 2014, Millendorf had gathered enough evidence to indict. Kanyok, Yang, and several others testified to a grand jury. Hadden was charged with five felonies and four misdemeanors involving six women.

A successful prosecution would rely in part on Columbia’s cooperation, including complying with demands for documents and alerting the government to important new witnesses. Instead, the university’s conduct helped the case against Hadden collapse.

Not long after the indictment, in August 2014, a former Hadden patient named Sandra Abramowicz had a panic attack. She was at work in a cardiac-research lab — at Columbia, coincidentally. She entered an equipment closet and thought of an exam with Hadden, a memory she had grappled with and tried to put aside: a sense of being frozen while on the exam table, unable to move. She suddenly began gasping for breath. “An incredible feeling that something horrible is going to happen,” she says. “I can’t stop crying. I felt trapped. Very, very trapped.”

Abramowicz began to reevaluate other memories. She had started going to Hadden in 2011, and at her first visit, he offered to perform a full-body mole check, which she declined. During another exam, Hadden offered graphic, unsolicited advice about sex, gesturing at different positions. “I remember looking at the nurse who was there like, ‘How do we stop this going on?’” Abramowicz recalls. “And she just looked down and sort of to the side. And I just felt then like, Okay, I’m alone here.” Abramowicz also remembers getting the “Dear Valued Patient” letter about Hadden’s departure and asking another Columbia gynecologist about it. “She very abruptly looked down, avoided my eyes, looked at something on her desk, and said, ‘I don’t know anything about that,’” Abramowicz says. “I thought, That’s weird. Because he was working in the same department. How could you not know why he left?”

After her panic attack, Abramowicz met with a different Columbia doctor and asked if there was any medical explanation for the way Hadden had touched her and spoken to her. It was by now clear to Abramowicz that she had been assaulted. The doctor left the room briefly and returned, saying that physicians in the practice had been instructed where to refer patients with complaints about Hadden. The doctor handed Abramowicz a yellow Post-it note with a name and number.

Columbia knew that the district attorney had an open investigation. But the name on the Post-it was not Laura Millendorf’s, and the number was not that of the public hotline the DA had set up for patients to report sexual assaults. It was Patricia Catapano, Columbia’s deputy general counsel, and her direct line.

Abramowicz tucked the Post-it inside her wallet. “The fact that she said, ‘This is where they’re referring former patients of Dr. Hadden’ told me I’m not the only one. And Columbia knows that I’m not the only one. And then the thing that hits me is, If she represents Columbia and I’m Sandy, whose interests is she representing here?” Abramowicz carried the Post-it for years but never called the number. (Reached by email, Catapano wrote, “I am retired from Columbia and have no interest in responding to this inquiry.”)

Columbia also didn’t alert prosecutors to the existence of other victims who might have strengthened the criminal case. And it neglected to make a report to the Office of Professional Medical Conduct, the state medical board, as required.

For almost two years after Hadden’s indictment, Millendorf pursued her inquiry, taking witness testimony and poring over thousands of medical records. But inside the DA’s office, she felt there was an aversion to the case, which was complicated and challenging. Prosecutions of sexual violence were often chosen on the basis of how easy they would be to win. In 2015, Vance passed on prosecuting Harvey Weinstein.

In February 2016, Hadden’s attorney, Kirshner, came to the DA’s office at 1 Hogan Place to put the case to bed. Kirshner knew the department well. She had previously worked as a prosecutor there and was so close to Vance that she’d asked him to officiate at her wedding. Meeting with his deputy, Friedman Agnifilo, Kirshner agreed to a deal: Hadden would plead guilty to one felony and one misdemeanor, be added to a sex-criminal registry, and surrender his medical license. He would serve no time behind bars or even perform any community service. The agreement also stipulated that he could not be prosecuted in the future for any similar crimes then known to the DA’s office.

Millendorf, who had not been at the meeting, was directed to tell Hadden’s victims that the deal was a “win.” Devastated by the weakness of the plea, she wrote up talking points — a list she called “Reasons Why Plea Good” — to keep herself on message as she dialed.

Kanyok was in the middle of holding a ballet audition when she got the call. “I was numb. I was absolutely numb,” she says. “That’s all? That’s all you get?”

Friedman Agnifilo thought at the time that the plea was a good one and that the survivors would be happy to be spared the agonies of a trial that might not have turned out the way they wanted. Today she feels differently. “It was just a wrong decision,” she says. “I can’t even make excuses for it. And I don’t even want to try.”

Two years after the plea, in February 2018, Kanyok was tired of fighting. After a grueling day of mediation with Columbia’s lawyers, she agreed to a settlement in her civil suit. She received $475,000 and signed a confidentiality agreement. After the settlement, Kanyok went out for a half-hearted celebratory martini, went home, and wept. The next morning, she broke down again standing in her kitchen.

She pulled herself together, walked her daughter to school, and hugged her good-bye. Outside, alone and spent, she collapsed on the sidewalk of Fulton Street. “I can make myself strong when I need to be strong. I can buck up to the best of things,” Kanyok says. “This was a breakdown like I have never in my life experienced. This was worse than Hadden.” When a friend tried to help her up, Kanyok — thinking of the agreement she’d signed — could not say what was wrong.

When Evelyn Yang’s husband, Andrew, announced his presidential campaign in 2017, she was so private she didn’t have any active social-media accounts. She remembers the internet trying to figure out her identity. “They would be posting these pictures of him with random women, captioned with my name, and I would laugh, like, Ooh, another decoy!” One day in 2019, as the campaign was attracting national attention, Yang received a disconcerting piece of mail from Columbia: a subpoena for a deposition by her husband. She thought it must be a mistake. Legally, she was still a Jane Doe; Columbia wasn’t supposed to know her identity yet. “And then I thought, Oh. They’re trying to send me a message — that they know who I am and that they know who my husband is,” Yang says. “It felt like a threat. Like, ‘We know who you are, so be careful. Because we can out you.’”

On the campaign trail, Yang had been sharing candid stories about her son’s autism. Voters responded by revealing their own trials. “There’s one letter I got in particular about a woman who stood up to sexual harassment at her job,” Yang says. “I was really moved by her bravery, and I started to reflect on my own Me Too story.” She began to wrestle with whether to go public about Hadden in hopes that it might help others coping with similar trauma. (Looking back, it isn’t lost on her that the move also robbed Columbia of the power to expose her. “They would never expect that I would do this,” she says, “and that was satisfying.”)

Yang contacted Dana Bash, the CNN anchor, whom she’d met on the campaign trail, and gave an interview that aired on the evening of January 16, 2020. More than 2,000 miles away, in Provo, Utah, Dian Saderup Monson was propped up in bed, working. Her husband brought up some dinner and suggested they watch the news. He switched on CNN. After a few minutes of watching Yang’s interview, he said that the doctor she was describing sounded a lot like the OB/GYN Monson had seen. She immediately searched the internet to learn more. “I had seen him in 1993, and she was assaulted by him in 2012,” she says. “Where was Columbia during all of that time?”

After Yang aired her story, dozens more Hadden victims began to speak out, and the scale of his crimes caught the attention of the U.S. Department of Justice. Monson’s letters helped to provide evidence of his crimes going back decades. The most promising path to conviction lay in charging Hadden with enticement — persuading women to cross state lines to engage in illegal sexual activity. In September 2020, acting U.S. Attorney Audrey Strauss announced his indictment at a press conference, calling him a “predator in a white coat.”

Millendorf had quit the Manhattan DA’s office by then. On the day of Hadden’s arraignment, chatting by phone with a former colleague, she learned that the DA had opened a criminal investigation into Columbia’s conduct. The official reason was the volume of new victims coming forward. But, of course, the politics of sexual abuse had undergone a sea change. Prosecuting it was more popular, and enabling it was considered more villainous.

Millendorf was infuriated to discover how much evidence Columbia had failed to turn over — or possibly even lost — during her investigation. The DA found that the university “expended little or no effort to preserve documents” and put in place no record-retention holds until April 2020 — an elementary step when an organization is involved in litigation. The university did not give prosecutors emails from Brenda Cruz documenting the patient complaint in October 2008 and noting that it had been discussed with John Evanko or an email exchange in October 2013 about another incident. Columbia also did not turn over critical pieces of Hadden’s personnel file, including his censure for inappropriate computer use and the letter from Harold Fox to Dian Saderup Monson.

In a letter to investigators, Cantwell, the attorney for Columbia, acknowledged that they should have produced certain documents in response to subpoenas. But she argued a technicality about the Fox-Monson letter and the computer-use note. Cantwell wrote, “On their face, neither document describes a complaint of patient abuse: one is an internal memo related to alleged inappropriate use of a computer which does not involve a patient in any matter and the other is a letter acknowledging receipt of a patient’s concern, but the nature of the concern is not discernible.”

Cantwell’s letter also outlined steps the university has taken to improve patient safety, including updating its chaperone policy, adding signs in exam rooms, and establishing a hotline and a database to track complaints. She also asserted, contrary to evidence, “the University’s overwhelming record of cooperation throughout both investigations.”

No one at Columbia was ever charged with a crime. “I think there was the sense that we could not demonstrate that the conduct was intentionally purposeful,” says Vance, who left his post at the end of 2021. He offers an apology for his department’s handling of the original investigation. “I am very sorry for the way our office managed this case and how the survivors felt they were not listened to,” Vance says. “That was unacceptable.”

In December 2021, Columbia agreed to a $71.5 million settlement with 79 patients who had filed civil suits; a second settlement, for $165 million with 147 other victims, came the next October. The university did not accept responsibility or apologize for any dereliction of duty. More litigation could be coming: DiPietro says he plans to file cases on behalf of another 250 patients.

After abusive doctors were discovered at UCLA, USC, Michigan, and Michigan State, those universities underwent reviews of the systemic failures that had allowed the misconduct to persist. Michigan State issued a formal statement of apology for its actions in the Larry Nassar case. Two university administrators faced criminal charges: The case against former president Lou Anna Simon was dismissed, but she resigned from her position, and the dean of the school of osteopathic medicine was convicted of a misconduct charge. At Columbia, no administrator above Hadden at the time he was arrested has been fired or disciplined in any way that is known.

In January 2023, Laurie Kanyok sat in the witness box at the Southern District of New York courthouse to testify at Hadden’s trial. A prosecutor asked her what navigating the justice system had been like. “It’s been a long time,” Kanyok said through tears, raking her thick blonde hair behind one ear. “My daughter is 10 years old. I called the police when she was 6 weeks old.”

Over the course of the two-week trial, witness after witness told stories of grooming and abuse as Hadden sat next to his state-appointed attorneys. One survivor, an Orthodox Jewish woman using the pseudonym Sara Stein, testified while wearing a headscarf according to the tradition of married women. A prosecutor asked why she had covered her hair that day even though she was now divorced. “It was a part of my body that he had never seen, my hair,” she said. “And I wanted to keep it that way.”

On January 24, the day of the verdict, a dozen women filed into two wooden benches and gripped one another’s hands. The judge asked the foreperson for the jury’s verdict on the first charge. “Guilty,” she said. The women audibly gasped. After the second “guilty,” many began softly crying. Hadden was convicted on all four counts he faced.

There was one more affront to endure. The judge announced that Hadden would be permitted to go home with his wife and son, both of whom have chronic medical conditions, pending another hearing. From the back of the courtroom, one of his former patients, a woman named Adina, rose to her feet: “Could I just say one more thing? He’s a sexual predator and we’re allowing him to go home to two disabled people and care for them? That doesn’t really make sense to me.” Hadden’s wife, Carol, who had attended every day of the trial, turned to face her. “Excuse me,” she said. “I am his wife, and there is no problem.” (Robert and Carol Hadden did not respond to requests for interviews.)

A week later, after hearing statements from survivors, the judge ordered that Hadden be detained. Eyes wide, he turned to face his wife as U.S. Marshals approached him with handcuffs. Three decades after his assaults began, he spent his first night behind bars on February 1. On July 25, Hadden returned to court for sentencing and received the statutory maximum sentence of 20 years for each of the charges against him, to be served concurrently. Standing at the defense table, facing the judge, between sobs, he said, “I’m very sorry for all of the pain I have caused.”

Some of Hadden’s former patients, including Yang, called legislators to push for the passage of the Adult Survivors Act, a New York law that opened a temporary window for victims of abuse to file civil suits against their abusers even if the statute of limitations has expired. The window will close on November 23. If any of Hadden’s victims miss that deadline, they will lose access to one of the best avenues for forcing Columbia to acknowledge their experiences — and possibly compensate them. The university has given no indication that it will otherwise reckon with the stain left by Hadden and its own actions.

Because Columbia refuses to notify all of the patients who saw Hadden during his career, an untold number remain unaware that this moment is fleeting. One of them might have been Belkis Hull if she hadn’t happened to see Hadden’s mug shot while scrolling through Instagram last winter. For more than a decade, she had dismissed her own experiences with Hadden, believing them to have been in her head. Learning the truth felt validating. “It’s pathetic and it’s so infuriating,” she says. “How can you trust an institution anymore? An institution that is as prestigious as they were. The only reason I went there was because it was Columbia.”

Laura Beil is a journalist in Texas who covers health care. She also writes and hosts the Wondery podcast Exposed, which is about the Robert Hadden case. Bianca Fortis, a former Abrams Report Fellow at ProPublica, is a journalist in New York. With research by Alex Mierjeski.