This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Ivana Trump’s house at 10 East 64th Street, which she purchased for $2.5 million in 1992 after her divorce from Donald Trump, is modest compared with the former mansions of Gianni Versace and David Geffen on the same block. Twenty feet wide with a 1920s limestone-column-and-pediment façade, it could pass for a small nation’s consulate or a mausoleum. Inside, it was all Ivana: red carpeting, gilded paneling, and animal prints. She was especially proud of the grand curving staircase with a mural, she once told People magazine, “painted on so it looks like it’s a balcony, looking into French-Roman gardens” — the backdrop for countless regal publicity moments with her posing in ball gowns, peddling a relentlessly queenly idea of herself almost to the very end, even as her realm had shrunk.

Her children and remaining friends (not everyone stayed loyal to her after her ex-husband became the kind of president he became) hated those stairs. Old skiing accidents and a more recent hip injury — she fell at one of her go-to restaurants, Avra Madison Estiatorio — had rendered “Glam-ma,” as she liked her grandchildren to call her, increasingly wobbly. She ignored her friends’ and family’s pleas to sell the townhouse and move into a hotel suite. They feared she would slip and fall down those stairs and hurt herself. At some point in the past few years, her kids bought her one of those emergency “I’ve fallen and I can’t get up” devices, but she refused to wear it.

“I was more concerned about her falling down those stairs than anything else, and she adamantly refused to move,” said her friend Nikki Haskell. “There are all these pictures of her on that stairway. When you think about how you are going to end your life, did she ever once think that is how it’s gonna happen?”

Which is likely what happened. On July 14, Ivana was found at the bottom of the stairs, dead after suffering, according to the medical examiner’s office, “blunt impact injuries” from the fall.

She had been giving the people who cared about, and for, her some cause to worry for a while. Especially since the induced isolation of the pandemic — she was extremely COVID cautious — she had become noticeably frail.

Friends say she enjoyed a drink, but as she got older, it started to take its toll, and they wished she would cut down or quit completely. She had reportedly done at least one stint in rehab. Tabloids, especially the Daily Mail, which was always up for publishing unflattering candid shots of her, reported on episodes of what appeared to be public inebriation and occasional meltdowns. In 2009, she was kicked off a plane after a “foul-mouthed” tirade aimed at some kids playing loudly in first class.

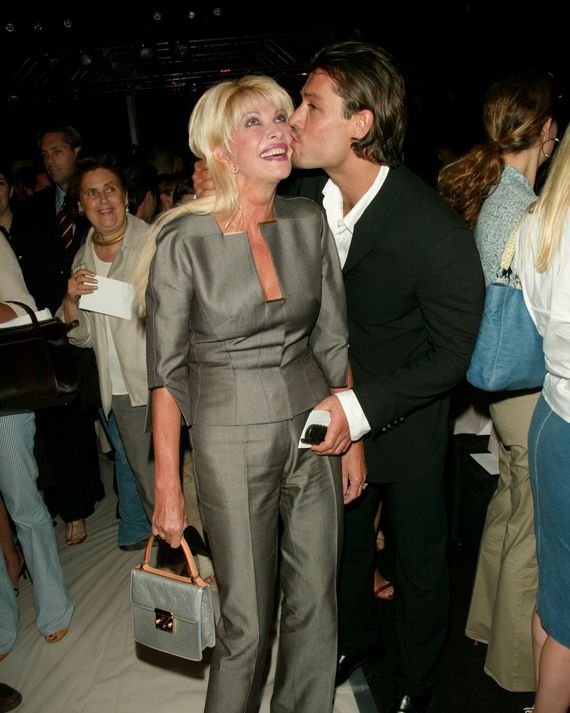

Most thought she was really undone by the death in 2021 of her last ex-husband: Rossano Rubicondi, the rakish Italian adventurer and former model, 23 years her junior, whom she’d started dating around 2002, married (at Mar-a-Lago, no less) in 2008, divorced a year later, and could never quite rid herself of.

Rubicondi returned to her for the last time in 2020 while he was suffering from cancer. She brought him from Italy, got him an apartment near her house so he could get treatment, and begged him to quit smoking, which he refused to do — debonair, friends say, almost to the very end.

He was, maybe even more than her second ex-husband — the one who became president — the tragic love affair of her life, a romantic error she couldn’t help but make. It was Rubicondi whom many assumed that Dorothy Curry, the former nanny to Ivanka, Donald Jr., and Eric, spoke of at Ivana’s funeral, referring to the “sinking swamp” of “parasites” who had kept her “afloat” with “illicit dreams and schemes.” As recently as 2018, when “Page Six” reported the couple was squabbling at La Goulue, Rubicondi was still telling anyone who would listen that he was planning on opening a pizzeria, Rossano to Go, presumably with Ivana’s backing, in the city (an earlier plan to open it in West Palm Beach had gone nowhere).

“I think Rossano’s death sank signora. She was very, very down; we could see it,” remembered Paolo Alavian, the owner of another one of her go-to restaurants, Altesi. As a doorman on her street told the British tabloid The Sun, “She used to always wear high heels and walk straight up … After he died, she didn’t come out as much. She wore flats and walked hunched over with a cane.” Massimo Gargia, the man who introduced her to Rubicondi, believes the combined effects of the pandemic and his death depleted her. “She was so depressed,” Gargia said.

Most of her friends told me they wished she’d never met Rubicondi in the first place.

Ivana Zelnícková always wanted more. She was born eight weeks premature in a drab shoe-factory town in communist Czechoslovakia on February 20, 1949. Her father, an electrical engineer named Milos Zelnícek, had wanted a boy and raised her sporty. He taught her to ski in the foothills of the Carpathians. On Saturdays, when they got off work at the Bata shoe factory, the parents of Gottwaldov (her hometown, since renamed Zlín) took their children out two hours by bus, hauling wooden skis with homemade bindings up hills with no chairlifts and overnighting in cabins heated with wood they collected.

Competitive skiing eventually got Ivana across the Iron Curtain, a rare privilege in the 1960s. As a teen on her first trips to the West, she fell in thrall to the sorts of luxuries — chocolates, fashions, jeans, Coca-Cola, and sports cars — that didn’t exist back home. In 1971, the same year her boyfriend George Syrovatka defected to Canada, she married her friend Alfred Winklmayr, an Austrian ski instructor, so she could get a passport to leave the country.

She divorced him before long and eventually moved to Montreal to be with Syrovatka and found work as a model. Then, on a trip to New York in 1976, she met Donald Trump; according to a 1990 New York Magazine profile of Ivana, he “spotted her across Maxwell’s Plum and used his pull to get her a table.” After she signed a prenup, they were married in 1977, the same year Don Jr. was born. (According to the New York article, she “fixed [Syrovatka] up with a girlfriend.”)

She was by Donald’s side for the next dozen or so years, helping him remake the Grand Hyatt, picking the pink marble for Trump Tower’s atrium, helicoptering down to Atlantic City to oversee Trump Castle, then returning to the city to run the Plaza Hotel, which he had purchased and renovated. (She even accompanied him on his first trip to Moscow in 1987, after which he declared his intention to run for president.) She also created Trump’s oligarch brand. She told Time in 1989, “If Donald were married to a lady who didn’t work and make certain contributions, he would be gone.”

They became the epitome of ’80s flamboyance. But as she gained more attention, he would undermine her. Lounging beside Ivana on a couch during one televised interview after he named her president of the Plaza Hotel, he watched her talk about how much she loved her work. When the reporter asked how much Donald paid her, she replied with a little giggle, “One dollar.” Donald chimed in, “And all the dresses she can buy.”

It all ran aground by the end of 1989 after Trump brought his mistress Marla Maples on a family vacation in Aspen. There, Maples confronted Ivana in public at a slope-side eatery, two big-haired women in expensive ski gear, in a scene straight out of Dynasty: “I love your husband. Do you?”

A protracted divorce followed that was extensively litigated in the tabloids. As it happened, just as their marriage imploded, his business crashed, leaving him $3.4 billion in debt. (Among the disasters and fire sales, he sold the Plaza for an $83 million loss.)

Ivana accused him of marital rape, and Donald invoked the Fifth Amendment 97 times in depositions. When it was all over, off she went with a $10 million certified check, $4 million more for housing, a 1987 Mercedes, and their nearly 20,000-square-foot Greenwich, Connecticut, mansion, which she sold for $15 million.

Researching for my book about Trump’s women in the Czech Republic, I met people in Zlín who believed their most famous ex-resident skied under the Iron Curtain like Matt Damon in The Bourne Identity, dodging bullets. They got that idea from a 1996 made-for-TV movie called For Love Alone, based on a roman à clef of the same name that Ivana wrote. According to IMDb, it “follows the triumphs and tragedies of Katrinka Kovár, a young Czechoslovakian ski prodigy who discovers high-society splendor in the arms of a wealthy American businessman. When lust turns to lies, Katrinka — long haunted by a burning secret from her past — sets out to find the love she left behind.”

Post-Donald, Ivana set about reinventing herself, starting with what became her trademark Brigitte Bardot–inspired hairdo, the one Joanna Lumley’s character, Patsy, loosely based on Ivana, wears on Absolutely Fabulous. She hit the talk shows — delicate, teary, vulnerable. She was branding Ivana with a vengeance, using everything she’d learned from becoming a Trump. YouTube is filled with Vaseline-smeary videos of her, blonde hair piled high, hawking silk blouses from House of Ivana priced to sell at $79.99 — always adding the 99 cents because people might pay anything but not a dollar more.

She trademarked clothes, perfume, bottled water, bath products, china, all under the Ivana brand. Besides matching Donald brand for classy brand, she tried to match his ego, plastering her name on everything, including a yacht she christened the M.Y. Ivana.

The “classy” Trump brand usually turns out to be just painted gold or mass-produced in China. This was also true of Ivana’s. She had money, but her wealth didn’t hide the foundational nouveau brass. Her beloved M.Y. Ivana cost $4 million, was 98 feet long, and had four staterooms and marble baths. It served as a weapon in her media war with her ex. “While Donald doesn’t even have a dinghy,” the New York Post wrote when she bought the yacht, “Ivana is in Monte Carlo kicking the tires of a spanking new vessel.” She proudly told reporters she had paid for it herself. “I make in one year three times what he paid me in a settlement. I don’t need Donald Trump’s money.” Donald responded with a public letter claiming she had paid twice what the boat was worth.

For the rest of her life, at least until the pandemic hit, Ivana was on the move, wintering in Palm Beach at a 12,000-square-foot house that she’d bought, like the 64th Street home, in 1992 after the divorce (and that she would eventually sell for $16.6 million to designer Tomas Maier, who resold it earlier this year for $73 million). She moved on to a Miami Beach condo in the Murano at Portofino, where, as recently as five years ago, she was witnessed rolling down her bathing-suit top poolside to apply sunblock while the building staff buzzed around her solicitously. She spent at least three months every summer at a trio of small former fishing cottages she owned in St.-Tropez.

Ivana adored the yacht-owner lifestyle, but her own boat seemed cursed. Sugar tycoon Alfy Fanjul sued her when the M.Y. Ivana slammed into his yacht during a Florida hurricane. Worse, according to a lawsuit she filed in 1997, it was “falling apart” as soon as she took possession. Two years after she bought it, she sued the Italian maker, Cantieri di Baia, for $35 million, claiming the yacht was “damaging her internationally ‘recognized persona.’ ” She claimed it was seven feet shorter than promised, didn’t travel at top speed unless it was empty, and had a faulty exhaust system that sparked a fire. In 2001, the company settled. Her attorney Gary Lyman isn’t sure who bought the yacht from her, joking, “It’s probably at the bottom of the sea.”

But while the M.Y. Ivana was sea-worthy, she needed a man to put on it. Donald Trump wrote (well, actually Tony Schwartz wrote) in The Art of the Deal that he had built Trump Tower not for “the sort of person who inherited money 175 years ago … I’m talking about the wealthy Italian with the beautiful wife and the red Ferrari.” That’s exactly what Ivana wanted, too. Or to be that guy’s beautiful wife or girlfriend, anyway.

An Italophile since her teen years, she worked her way through three Italian men. Numero uno, businessman Riccardo Mazzucchelli, married her at the Mayfair Regent in New York in 1995. She wore a blue satin dress and a diamond necklace with a “piece of ice as big as the Wollman Rink nestling in her décolletage.” The marriage lasted two years, foundering, friends said, over his jealousy at her Home Shopping Network success. Her prenup (she had been schooled in that unromantic art from enduring years of litigation over the ones Donald made her sign) protected her from his attempts to get a piece of her fortune.

Numero due, Roffredo Gaetani di Laurenzana dell’Aquila d’Aragona Lovatelli, was from, as she liked to put it, “an important family.” Their relationship lasted five years before he died in a car accident on an icy Tuscan mountain road at age 52. She told friends he was the best lover of her life. “I cry whenever I think about him,” she wrote in her 2017 memoir. “I have no idea why I didn’t marry him.”

As Ivana tells the story in her 2017 book, she met Italian numero tre at a party for 200 she hosted on M.Y. Ivana when it was docked at Cannes for the film festival. Her friend Gargia brought Rubicondi — a “young, nice, very good-looking trim stylish man” — along as his guest, and they hit it off. By the end of the summer, she’d invited him to cruise with her from St.-Tropez to Sardina and professed to be shocked when she found out his age when she later took a peek at his passport. But she soon got over it, and he became the love of the last third of her life. As she wrote, “I’d rather be a babysitter than a nursemaid.”

Rubicondi was born in Rome in March 1972, 23 years after Ivana. Handsome, with a full head of brown hair and Cupid’s-bow lips, he had occasionally modeled and acted in Italian and American movies (including a small role in the 2000 adaptation of Henry James’s The Golden Bowl with Uma Thurman).

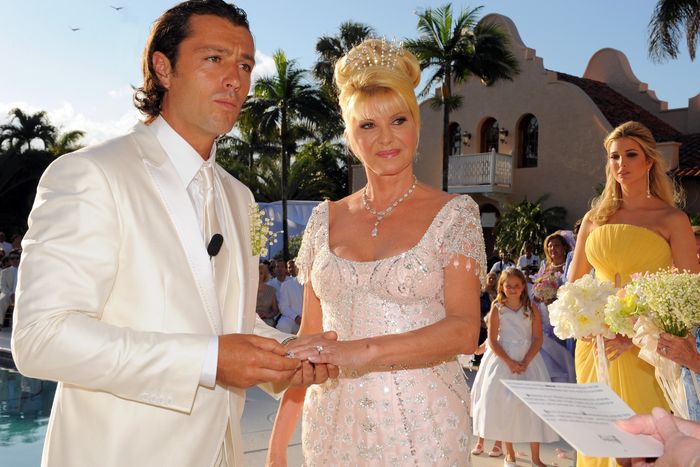

For six years, they dated, threw tempestuous tabloid-ready fights, kissed, made up, and went at it again. Her friends assessed Rubicondi as a classic fortune hunter, “a snake.” At Mar-a-Lago in 2008, she married him anyway.

Donald’s sister Maryanne Trump, then a federal judge, officiated. Haskell, her matron of honor, refused to read lines the judge handed her before the ceremony. “It was something like, ‘Thou loveth and holdeth thy dear to thy heart and will cherish,’ ” she said. “And I read the thing over and I said to her, ‘I don’t think we should really read this because this marriage isn’t going to last that long.’ ”

At the reception, Don Jr. gave Rubicondi a “welcome to the family” speech straight out of The Godfather: “We are a construction company, and we have job sites, we lose people … You better treat her right because I have a .45 and a shovel.”

The guests, many of whom were European, didn’t know whether to laugh or be horrified. “It was sort of a timid haha, haha, haha. You heard a chittering going through the crowd,” one guest recalled.

“The whole family was against it,” said her friend Gargia, an Italian PR man, sometime actor, and fixture on the French Riviera. “Even Ivanka said, ‘Why did you introduce him to my mother?’ ” In his defense, he said he knew Ivana was grieving over her lost lover and needed some fun. He didn’t expect it to end in a wedding. “I feel guilty that I introduced them,” he said. “It was fine for six years while he was a boyfriend. But the minute they got married, he changed.”

At the ceremony, Rubicondi charged down the aisle fist-pumping to the Rocky theme, then promptly ran off with a younger Cuban girlfriend.

He and Ivana divorced a year later, but she never cut the cord. For the next 13 years, until his death, the boy toy swanned in and out of her life, often trailed by paparazzi. There they were, walking her dog Tiger One on a leash on the St.-Tropez promenade, Mediterranean pines in the background; canoodling near the yachts, Rubicondi in sea-breeze-rumpled hair and surfer trunks, Ivana in designer kitten heels and a tropical wrap dress; posing in evening clothes beside a giant birthday cake for her at the Hotel la Mistralée. Back in New York, Rubicondi wore a Donald Trump costume to escort her to a Halloween party in 2004 (you can buy a photo of this at Walmart). The tabloids loved their public fights, too, including the time Ivana threw his clothes off her yacht. He enjoyed his wine, as she did, and, in 2016, even called the police on himself for driving drunk near Mar-a-Lago.

In between their breakups and makeups, Ivana’s ex-husband became president. This was complicated for her. On a cold, slushy day a few weeks before the inauguration, she visited the studio of fashion designer Marc Bouwer to select some dresses. Bouwer was an old friend but hadn’t seen her for a while. She looked, he thought, surprisingly downtrodden. Ivana never let things get to her like this.

Bouwer and his partner, Paul Margolin, helped her inside, where she started sobbing. She was hysterical and they held her. Soon, the two men were also overcome. She said people were shouting hateful things at her and protesting outside her house. “And I’m not even married to him anymore,” she wailed. “It’s not my fault!”

Ivana shared many political views with her ex, starting with a devotion to unfettered capitalism, “doing deals,” and adopting the transactional mode in all of her relationships. An immigrant herself, she told a British TV network during his reelection campaign that U.S. immigrants “steal and rape women” and “don’t get jobs.”

At a crucial juncture in the campaign, while Donald was fighting off sexual-harassment accusations, she even downplayed the rape allegations she had once made against him. Still, “in Washington for the inauguration, she had a very bad seat,” Gargia said. “So she left. She was in shock to see where they put her. It was a little exclusion.”

Furrier Dennis Basso, one of the few people to speak at her funeral, summed up her attitude about her ex’s election: “Divorce is difficult, even if you own a little shop in the smallest town in America and that person gets remarried. I am putting politics aside; politics is not part of the picture. Nobody wants to get divorced and have their husband or wife become the most powerful person in the world.” Her friends said she was convinced she would have been a better First Lady than Melania.

Ivana had a competitive streak and an instinct for turning relationships into transactions. The boy toy and the yacht were fun, sure, but they were also proof she was making it. Yet it can be hard to maintain dignity and faith in one’s seductive powers, especially for a woman who made her beauty central to her personal brand. Rubicondi apparently kept that faith alive. Ivana glowed, giggled, and got girlie whenever he showed up. Even that was fleeting.

In 2020, Rubicondi was diagnosed with melanoma. He was in Italy, needed treatment, and had no money. That fall, in the middle of the pandemic, Ivana paid for his move to New York and set him up in an apartment around the corner from her on Madison Avenue, arranged with the help of another Czech émigré girlfriend, a Sotheby’s Realtor. She had wanted to be a babysitter but ended up a nurse.

The “snake,” as her girlfriends still called him, was now her charge. “I can’t say his name,” said her friend Vivian Serota, a Manhattan mondaine and widow of the Long Island commercial-real-estate magnate Nathan Serota. “Nobody could stand him except Ivana. There was no sex, either. Nothing was happening except that she paid for him and he brought her breakfasts in the morning.”

Not only could Ivana stand him, she still liked him a lot. “There are always the two girlfriends who don’t like the boyfriend,” Basso said. “Look, he was young and good-looking. Ivana and I used to say to each other all the time, ‘Every day is not Christmas.’ I spent many summers on her boat in the Mediterranean with Ivana and Rossano, and we had fabulous times. Was he the greatest catch in the world? No. Was he dashing, and did they have some fun? Yes.”

A New York Democrat who worked with Ivana agreed. “Rossano gave her what nobody else did. He was this younger man she could be girlie and flirty and sexy with. Why is it any different from an older man who puts up a younger woman as his partner?”

In his last year, between visits to Sloan Kettering for chemo on her tab, he would often accompany Ivana to her table at Altesi. “Signora paid for everything,” its owner, Alavian, remembered.

Rubicondi was dreaming up wacky money-making schemes to the end. He talked about building a pizza oven in a fire truck and running a restaurant out of it, but he needed $200,000. Ivana told him she would pay for it but only if he stopped smoking. A Marlboro Red pack-a-day man, he did not give it up. Puffing away on the terrace at Altesi, he didn’t even look sick.

“Look, I can’t judge love,” Ivana’s attorney Lyman said. “They had a continuing relationship. As to the quality of that relationship, I don’t know any of us can judge. She was pretty distraught after he died.”

Rubicondi died in October. Ivana grieved all winter and was still grieving when she died. She put on a brave face with friends, but some days she would turn up at Altesi and sit alone nursing Pinot Grigio.

On these days, the staff would take turns talking with her, trying to cheer her up. Once during this period, “she looked terrible,” remembered Alavian, and another customer snapped a picture of her. “I was extremely upset when she was disrespected. But she always said, ‘Don’t react, forget about it.’ ”

Finances were not an issue for her, according to her lawyer. She had assets and significant real-estate holdings and had received a “multi-seven-figure” advance for her 2017 memoir, negotiated by her literary agent, Dan Strone, the CEO of Trident Media Group. That book, Raising Trump, was published in fall 2017. Sales were disappointing. MAGA didn’t buy. Not much love for those kids in other markets.

Her will is being probated privately in Florida, and no further information was available at press time. Despite her assets and properties, some friends noticed signs that she was perhaps not as wealthy as she had been. She told one friend she wanted to sell her Miami condo; perhaps she had simply taken to economizing as older people sometimes do. Bouwer noticed that the last time he saw her preparing to leave her house for St.–Tropez in 2017, her Louis Vuitton luggage was repaired with duct tape.

The pandemic hit Ivana hard. No more red-carpet posing at premieres, one Blahniked foot forward and turned out, catalogue-model style; no more holding court at “her table” at Upper East Side eateries. She was terrified of the coronavirus. She took seriously all the recommended precautions and isolated herself inside her Manhattan townhouse. She had always declined personal security, even after her ex was elected president. She ordered a lot of delivery from restaurants on her block between Fifth and Madison, takeout cacio e pepe or pappardelle pesto.

When restrictions eased, she stepped out a little. The months of isolation and the new hip injury showed. Alisa Roever, a younger Russian woman Ivana came to pal around with in recent years, saw a distinct change. “She was very active before COVID, very organized and extremely disciplined, up at six o’clock, on the treadmill reading all the newspapers before breakfast,” Roever said. “The COVID slowdown made her age. She was still put together, still had the hair and nails, but the energy wasn’t the same.”

She didn’t quite lose all her zest, though. She could flirt outrageously with younger men and tell dirty jokes. “She would unbutton my shirt and say, ‘Darling, please, open it up, the women will go crazy for you, you’re so hot,’ ” recalled Hamptons restaurateur Zach Erdem of his occasional customer. “I knew that she liked young guys — who doesn’t like hot guys? We joked a lot.”

One night, dining with Serota and the actress Brenda Vaccaro at Fiorella, where Ivana had a regular booth, the topic turned to sex and young men. “Do you want one rare or rarer? What am I talking about?” Ivana said. “A piece of steak? Nope. Rare or rarer?” She gestured with her hands: short or long. Oh, they got it. She meant a penis.

As soon as Broadway reopened, Ivana masked up and, armed with sanitizer to swab on the seats, hit the Saturday matinees. She favored shows with hot young actors. With Serota, she saw Jersey Boys three times, and at Moulin Rouge, she swooned over the actor Derek Klena.

The last paparazzi photo of Ivana was snapped two weeks before her death. She is walking up Madison, looking chic in big sunglasses, black flats, and a black sweater and slacks, nails manicured red, blonde hair tucked into the signature French twist, her back just slightly showing the beginning of the dowager hump, and leaning heavily on the arm of her housekeeper.

“She could not walk. There was something wrong with her feet,” said New York Social Diary publisher David Patrick Columbia, whose company took the picture. “She looked very, very uncertain. She was holding tightly on to a woman who was clearly an assistant.”

Her friends thought Ivana needed a hip replacement since injuring herself falling at Avra. “She tripped over someone’s purse straps and really injured her hip,” said Haskell. “Ivana was not one to ever complain. She was afraid of doctors; she was an anti-doctor person. Ivana never had a Band-Aid in her house.” The hip hurt enough that she went for a cortisone shot, but the long needle terrified her, and even though the drug lessened the pain, she didn’t go back.

Gargia, who was supposed to dine with her in St.-Tropez the day after she was scheduled to arrive, couldn’t bring himself to travel to the funeral. “Perhaps if she had survived, she could be in much better health in St.-Tropez, living a different life and so on.”

The day before she died, Ivana was the happiest she’d been since before Rubicondi’s death. She was primping for her first trip to Europe in three years. There was a lot of maintenance to catch up on: a dental appointment and then to Frédéric Fekkai on Madison Avenue to get her hair done. She was scheduled to fly on Friday night from JFK to Nice, where a helicopter would be waiting to take her to St.-Tropez. She was giddy.

That afternoon, she called Serota to see if she wanted to meet for an early supper at Altesi. Serota was also preparing to travel to Europe the next day and declined. They agreed to meet in St.-Tropez.

The last people to see her alive were her housekeeper, Fabiana Carbo Chavez, and Curry, the former nanny who now worked as Ivana’s assistant. Around 6 p.m., Ivana asked Carbo Chavez to walk a hundred yards to buy some takeout soup. Back home, the staff watched her climb that winding staircase and said good-bye for the night.

Serota was in the habit of calling Ivana every day at 8:30 a.m. The next morning, Ivana didn’t answer. Serota chalked it up to pre-trip preparations. At around nine, Carbo Chavez arrived as usual. She found the door locked from the inside. That was odd. An early riser, Ivana normally undid the inner lock before the housekeeper arrived. The key didn’t work. She rang the bell, and when no one answered, she called Curry. Eventually, they rousted the house handyman, who came over with tools to open the door.

Ivana was on the floor in her pajamas at the bottom of the stairs. Hysterical, the two women called Eric Trump — Ivana’s only child who still lived in the city — who rushed over from his nearby apartment and held his mother’s body until police arrived. The NYPD clocked the emergency call at 12:40 p.m. and pronounced her dead on the scene.

Her Yorkie, Tiger Two — Tiger One had died in 2017 — was the only witness to what had happened.

More From One Great Story

- They Missed Their Cruise Ship. That Was Only The Beginning.

- What Is MAHA?

- The Press Is Down and Shut Out in Palm Beach

- Finding Jordan Neely