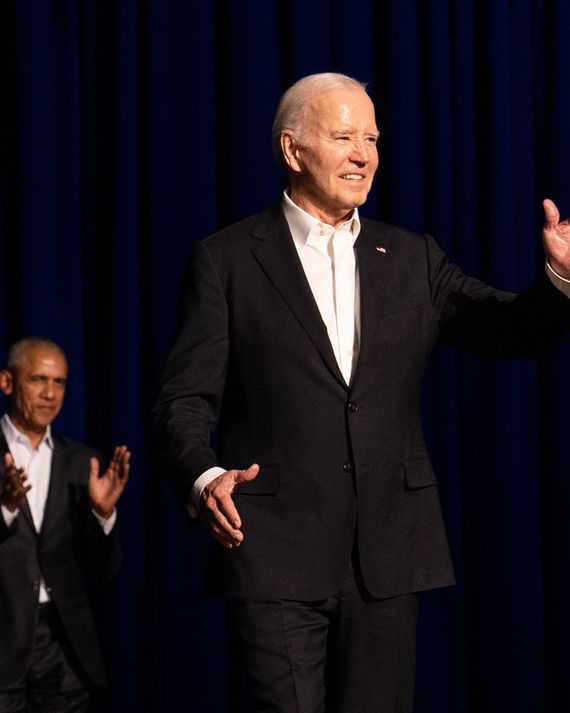

In 1965, when Joe Biden was 22, still seven years away from being elected the youngest senator in the country, Bob Dylan wrote, “Even the president of the United States sometimes must have to stand naked.” Now, nearly threescore later, the prophecy appeared to be fulfilling as Biden stood onstage in Atlanta, as white as a sheet, as frozen as an oil painting, rummaging through frayed neural pathways for the words, any words, to escape the linguistic corner into which he’d stumbled.

Words! Where were the words? Detoured in the transition, stuck to the tip of his tongue under a gob of Poligrip? How long did it last, two seconds, three? It might have been forever: Scranton Joe, the working-man’s friend, in stop motion on one-half of the split screen, Trump on the other with his silver-spoon-sucking smirk, a sadist calmly watching a drowning bug. He didn’t even have to say “I told you so.” In front of millions of people, Joe Biden, president of the United States, all 81 years of withered mortality, was standing naked.

It wasn’t pretty. Naked old people rarely are — all that sagging skin, the lumpy bottom, hair on their ears, toenail fungus, the inevitable way of all flesh, as if Dorian Gray’s Polaroid is developing before your eyes. The mere glimpse of demise sent the entire New York Times editorial board into panic mode and scared the bejesus out of the members of the president’s feckless day-late-dollar-short party, who are now racking their brains about how to get rid of him. Considering the stakes, nothing less than the onset of the New Dark Ages, the rancorous despair was justified.

This Old Man

This Old Man

For myself, I wanted to wring Biden’s turkey-wattled neck. I mean, what was he doing, setting himself up to be savaged by Trump, whose apparent unchanging appearance suggests some cut-rate Faustian connection? What kind of purple-carpeted hubris was telling him not to step aside or even shift tactics to combat the already-in-motion agenda of Project 2025? His “bad day” threatened to turn into a “bad month,” as he mixed up Putin and Zelenskyy, called Trump the vice-president, affording the Orange Man another belly laugh at his expense. Still, being a staunch secular humanist, I struggled to see these events through a sympathetic eye.

I say this because I know that look on Biden’s face, the lost-in-space gait, the way the words appear to hover just beyond reach. I’ve seen it all my life, first as a child with my relatives, hardy Brooklyn immigrant survivors of steerage compartments, great aunts and uncles who slipped me shiny quarters, took me to the zoo. Loved ones, diminishing before your eyes, not that I quite grasped the process at the time. I saw it, too, with my father.

Born in 1920, he wanted to be an engineer but opted for the security of the civil-servant life, becoming a New York City teacher, the way Jews did back then, like the Irish became cops and Italians sanitation men. But he continued to build things, moonlighting as a carpenter. Once, he bought a wrecked 19-foot sailboat and spent the next five years rebuilding it in our Fresh Meadows, Queens, garage. When my children were born, Dad made them the most spectacular things, handmade dollhouses and the great Cedric, the Seattle Slew of rocking horses. Then, one day, Dad brought by a couple of flagpoles he’d made for some festival the kids were planning, but something wasn’t right. They were not the same size; he hadn’t done some of the finishing work. It was a shock to me. Everything else that had ever come out of his workshop had been perfect. There was nothing to say, not until I saw him looking at the poles, shaking his head. “I must be getting old,” he said.

The ingress of the years is a constant topic among my contemporaries, many of whom I came up with in the journo biz back in the 1970s and ’80s, people who brought the news, fresh off the press, to curious minds. Several of them are now dead, more dropping all the time. Every loss feels like a disaster, as if you’re standing on a receding glacier. As for the rest, we hang out when we can, lamenting our catalogue of aches and pains, bitching about how people as cool as us continue to be targeted by come-ons for Publishers Clearing House and fluky medicine brands with sci-fi surnames and a speed-babbled list of contraindications that usually ends in “death.”

Like most our age, we talk about the good old days, the bohemian things we did, like party all night, hitchhike across the country, screw without Viagra. We talk about the movies and music we liked, and how what we knew — obscurities like the fact that the directors Joseph Losey and Nicholas Ray were from the same small city of La Crosse, Wisconsin, born two years apart (1909 and 1911) — amounted to the intellectual capital that set us apart, separated us from the squares. We talk about how no one cares about that anymore, tell tales like being in Paris and wanting to visit the home of Robert Bresson, whom we revere, except the block was closed, a production assistant screaming in French to get out of the way because they were shooting a “very important” soap commercial. We talk about the time we were on an airplane and the young woman sitting in the next seat was laughing at a comedian and then she asked, “Well, who do you think is funny?” And how we wanted to be safe here because we knew that anything the slightest bit out of the mainstream, like say Lenny Bruce, would result in that soul-searing “Who?” So we say “the Marx Brothers,” which also draws a blank and we feel like shooting ourselves.

One thing us oldsters have to accept is that the world no longer belongs to us, not like it once did. The torch has been passed. Like the other day, I’m in the bodega at the end of my block in the Slope, where I’ve lived since 1992. I’m buying the usual, Greek yogurt, strawberries for the grandchild, half-and-half for the wife. The bill is a typically outrageous $24.14. I’ve got a couple of 20s, some singles, and what feels like a ton of coins in my pocket. It seemed like a moment for exact change. As I fumble around, a dime falls out of my hand, lands on the linoleum floor, and begins to roll. True to my Queens upbringing, I chase it, much to the chagrin of the harried, frazzled young moderns lined up behind me, squawking toddlers in tow, all of them thinking, What is wrong with this old fuck? Couldn’t he use his phone to pay like everyone else?!

My wife says I should try to make myself more presentable to younger people, assuage the dread the sight of my crumbling corpus seems to trigger in them. If I want to peddle my however moth-eaten ideas to these generational-wealth aggregators, my wife says I will need to improve my table manners, stop getting $20 haircuts at Astor Place, and upgrade my wardrobe, perhaps opting for a seersucker jacket like the one rocked by writer Tom Wolfe before he went all white. That way, I will look like a “cool” old person, an aging bon vivant, like William Powell in his Thin Man roles, cocktail in hand. This is the sort of old person young people want to be if they should live so long, my wife tells me. Anything less conjures up dread images of forgotten Medicare recipients in nursing homes, unable to feed themselves or remember their names, the poor souls about whom everyone says, “If I get like that, just pull the plug.”

What it comes down to is this: How old is too old?

A few weeks ago, shortly before Joe Biden’s cognitive Waterloo, Willie Mays, the Say Hey Kid, the greatest, most beloved baseball player of all time, died. There were tributes to Mays, replays of his famous catch off Vic Wertz at the Polo Grounds, footage of him playing stickball with kids in Harlem. Yet in New York, where Mays had been young, each great feat was interlaced with a far more somber memory: that time when the Say Hey Kid, playing out the string for the Mets, stumbled around the bases in the 1973 World Series. Mays lived another half-century after that day, but many found it impossible to put out of their minds the moment he got “old.”

Everyone gets old in their own time, but when are they “too old”? Was Joseph Biden “too old” that night when he froze up in the debate against Trump? No doubt about it. Biden is 81, an old 81, with more miles on the odometer than most. He is a man from the past, as he’s been reminding us this week, the last in the long line of FDR Democrats. It seems unlikely he knows how to hook up a printer to a laptop. I wish he would have called me up before wandering onto the stage. I’m only 76, five years younger, I have never been president, never had to stand naked. But I could have told him there are some things I can no longer do, like think fast, and there are some things I do better than I ever could, like see the way big ideas come together, what they mean. Then, of course, I doubt Biden would have listened to me. He’s an old man; they are contrary like that, but human, all too human.