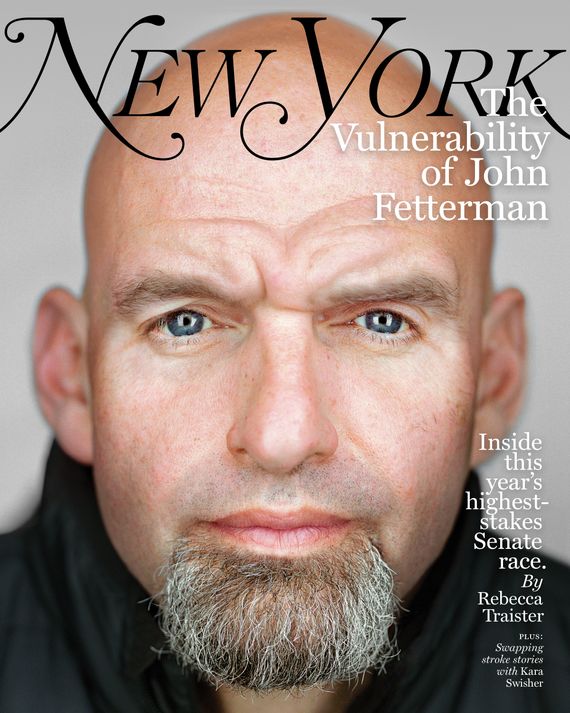

Even before John Fetterman became the Democratic nominee for Pennsylvania’s open U.S. Senate seat — one of the pivotal few that could flip from Republican control — he had attained folkloric stature. He was six-foot-eight, bald, bearded, and almost always in a hoodie. He had a Harvard postgraduate degree and a home in a converted auto dealership across from a steel mill in Braddock, the struggling former steel town in western Pennsylvania where he had been mayor from 2006 to 2019. An enormous white man who had played offensive tackle in college and appeared to be built of all the XXL parts at the Guy Factory, Fetterman made arguments for a higher minimum wage and prison reform and abortion access and legalizing weed at a frequency that could be heard by Rust Belt voters, and he had been regularly reelected mayor of his majority-Black town before becoming lieutenant governor. He was a Democrat who defied the right-wing caricatures of the contemporary left as elite, effete, and out of touch because he was self-evidently none of those things.

Political reporters were gobsmacked; they’d never seen anyone like him before. Sure, on some level, he was exactly the same as every other senator in Pennsylvania history, a white man. But he wore shorts in January!

Fetterman never had to work to connect with the kind of white voters Democrats have been bleeding over decades — voters who are less educated, less wealthy, and less urban, and who have flocked in ever-greater numbers to Donald Trump and his increasingly radical Republican Party. It’s not exactly that Fetterman was what the Democratic Party wanted — it supported his primary opponent during his first Senate run in 2016 and was largely keener on moderate Conor Lamb this cycle — but he was perhaps what they needed: the unicorn who could persuasively pitch policies that would make voters’ lives materially better while conveying in every word and gesture that he was one of them.

Then on May 13 he had a stroke. Four days after doctors removed a clot that could have killed him, he won the Democratic primary. Fetterman’s greatest strength — his indestructible guy–ness — was jeopardized, his infirmity seized upon by his Republican opponent, Mehmet Oz, who happens to be a doctor. “I’m so profoundly grateful,” Fetterman told me of his recovery during an early-October interview. We spoke using Google Meet, because the stroke had made it difficult for him to process what he hears; the video chat has closed-captioning technology that allowed him to read my questions in real time. “But running for the Senate, in the biggest race in the country, and having to recover at the same time is unprecedented.”

Fetterman spent much of the summer in recovery. He could not campaign in person, but he launched a social-media blitz viciously teasing Oz for being, until very recently, a longtime resident of New Jersey. Oz’s aim increasingly became to depict this broad, tattooed giant as weak and deceptive, secretive and soft on crime — a playbook the right has used successfully against Democratic candidates of all kinds but especially those who are not white men.

As summer turned to fall, Fetterman returned to the trail in person, powering through his convalescence at rallies and via television and newspaper interviews, his physical condition visibly improving. “Standing up in front of 3,000 people and having to talk without a teleprompter or anything? That is the most pure example of transparency there is,” he told me. But polls have tightened sharply in recent weeks, and the race has boiled down to a few issues: Fetterman’s team has continued to hammer Oz about living in New Jersey, his history of promoting medically dubious products on his daytime talk show, and his opposition to abortion, an issue that hovers over every race in America right now and underscores the vital importance of Fetterman’s victory, which could help Democrats keep control of the Senate.

But what gained more traction in September and October in both the right-wing multiverse and the mainstream political press were the attacks coming from Oz’s camp — as well as a Mitch McConnell–aligned super-PAC — suggesting that Fetterman was weak, both physically and in his approach to crime.

Tucker Carlson said that Fetterman is “brain damaged” and “can barely speak,” and has joked about his “stupid little fake tattoos,” comparing him to a “barista in Brooklyn dressing like a lumberjack.” Media Matters reported that in September the Fox News prime-time lineup mentioned Fetterman more than any other candidate, including those in other hotly contested Senate battles, a metric that illustrates how scared Republicans are about losing this race. “No one is ever fully ready to have an entire gigantic media organization just unload on you,” Fetterman told me. “To have lies weaponized with tens of millions of dollars. There’s aspects of that that are surreal.” Meanwhile, the New York Times and the Washington Post have echoed the Oz campaign’s suggestions that Fetterman is hiding something about his fitness to serve, running editorials pressing him to do more than the single debate scheduled for October 25 and for the release of further medical records.

The Oz campaign has also zeroed in on Fetterman’s commitment as lieutenant governor to granting clemency to prison inmates who have been wrongly convicted or served overlong sentences. Oz’s spokesman, Barney Keller, repeatedly described Fetterman during a phone call as “the most pro-murderer candidate in the entire country.” These attacks have gained attention in the mainstream press, including at the Times, which ran a reported story putting Fetterman’s time on the state’s Board of Pardons in the context of the nationwide anxiety about rising crime rates.

Fetterman has responded to Oz with scathing humor and also, increasingly, by being direct about his condition. At a September rally in Bethlehem, he mocked Oz for blaming Joe Biden for the closing of Bethlehem Steel, which happened 27 years ago: “And I’m the one who had a stroke!” Even more pointed was his insight into what it’s like to recover from a medical catastrophe in the midst of a punishing campaign for the U.S. Senate. “I guarantee you,” he told the crowd, “there’s at least one person in this audience that’s gonna be filming me, hoping that I miss words, that I mush two words together.” He paused. “Such an inspiring campaign he’s running, isn’t it?”

In the final weeks, Fetterman is banking on the hope that voters will see in his vulnerability a new way to appreciate his strength. In our conversation, he was lucid and animated, eloquent about the stakes of the race and incensed about the nasty tenor of Oz’s campaign. There were also moments in which his syntax got snarled or he had trouble getting a word out. “I really can’t hide it even if I wanted to,” he said.

It was Fetterman’s wife, Gisele Barreto Fetterman, who noticed that her husband was experiencing stroke symptoms. He had been on the trail constantly in the last days of the primary and had felt increasingly unwell. As long as he didn’t have COVID, the attitude on his campaign was that he’d better keep going. But on a Friday morning in May, the couple had just gotten into a car in Lancaster, headed to an event at Millersville University, when Gisele noticed that the left side of her husband’s mouth was drooping and that he had begun to slur his speech.

Doctors soon determined the stroke had been caused by a clot that had formed in his heart during an episode of atrial fibrillation; they removed it via thrombectomy. On May 17 — primary Election Day — Fetterman had another surgery to insert a pacemaker and a defibrillator, this to treat a more serious diagnosis of cardiomyopathy, a long-term condition that can lead to sudden death if untreated.

Fetterman told me he remembered waking up from that surgery on Election Night and learning, around 8:30 p.m., that he had won. He promptly fell back to sleep. Gisele appeared at her husband’s victory party to make his speech for him, joking, “I saved his life, right? I’m never going to let him live that down.”

“I left the hospital and went immediately to the stage to accept the nomination,” Gisele told me before a Montgomery County rally in early September. “So I didn’t really get to cry about it yet. I think November 9, I will process all these things that I have had to just carry because it is such a crucial race.”

Gisele, who works in nonprofit and mutual aid, possesses all of the aesthetic glamour and delicate grace Fetterman lacks. A foot shorter than her husband, the formerly undocumented immigrant from Brazil has long been an important interlocutor for him. “John is completely, almost awkwardly shy,” she told me. “I mean, we’d be at events and he would be in a corner.”

By contrast, Gisele loves people. She loves talking to people in ways that are emotional and open and disarming and funny. “If John doesn’t radiate sunshine, that is all that Gisele is and does,” said Kipp Hebert, the campaign’s unofficial creative director, who has worked with Fetterman since 2016. Gisele now often found herself the de facto face of her husband’s campaign, all while trying to shepherd him through recovery and manage the worries of their three kids. “Every doctor said he’ll make a full recovery,” she said when I wondered if she’d considered asking him not to run in order to focus on his health. “So it was not my place to stand in the way. This is something he has to do. And to see now that it kind of stands on him … it’s a lot.”

Of their kids, Gisele said, “It’s been a lot for them to process, and I hope they don’t need too much therapy — but we all need therapy, so it’s okay.” In most ways, she’s quick to point out, “we’re no different than every family that has to go through these health crises. The difference is that my family had to go through this publicly.”

The campaign, which had taken criticism for being slow to provide details of the stroke, released a letter on June 3 from Fetterman’s doctor, Ramesh Chandra, describing how he had diagnosed the candidate with atrial fibrillation in 2017, along with an irregular heart rhythm and a decreased heart pump, and saying Fetterman had neither returned for a follow-up nor seen “any doctor for 5 years and did not continue taking his medications.” (In the wake of those diagnoses, he did lose a lot of weight, dropping from a high of 418 pounds to 270.) Fetterman sheepishly admitted in an accompanying statement, “Like so many others, and so many men in particular, I avoided going to the doctor, even though I knew I didn’t feel well,” adding, “As a result, I almost died.” Chandra stated that as long as Fetterman “takes his medications, eats healthy, and exercises, he’ll be fine.”

But stroke recovery takes time, and here he was, the Democratic candidate for Senate, unable to campaign in the summer before an election upon which the future of abortion, labor and voting rights, climate change, and health care may depend.

In those first weeks and months, Fetterman could not deliver a speech or fundraise in person. What he could do was undertake doctor-prescribed walks of three to six miles every day on the trails around his Braddock home, during which he thought about the campaign. He had always been deeply immersed in his own team’s strategizing, rejecting language that he called “poll-tested bullshit.” “I just try to be the kind of individual that I would want to vote for,” he told me. “I believe in speaking the way I am and acting the way I really am.” Before the stroke, he would spend hours on the phone with staffers chewing over issues and messaging; his senior adviser Rebecca Katz, a native Philadelphian who has been advising him since 2015, called him the “brainstormer-in-chief.”

“Within a week or two of him getting home from the hospital, it was starting to ramp up again,” said his communications director, Joe Calvello, “but instead of phone calls, it was Google Meets or text messages.” From early on, the campaign said, doctors told them that Fetterman’s cognitive abilities were not damaged by the stroke. The biggest impairment was to his ability to process what people were saying or, in the beginning, even his own voice. His team’s text-based communications would prove crucial to the unorthodox social-media campaign they were about to launch.

It might have been easy to assume this summer that Fetterman’s deft tormenting of his opponent via Twitter was masterminded by a clutch of young digital staffers like the teenagers who ran former Alaska senator Mike Gravel’s presidential campaign. But the originator of the meme attack wasn’t three kids in a Fetterman coat; it was Fetterman himself.

“John was never a candidate where we had to explain, ‘Hey, here’s what a meme is,’ or ‘You know why this is funny, right?’ ” said Calvello. “We have an amazing campaign team for sure, but that was his voice,” said Gisele, whose Twitter bio reads SLOP (Second Lady of Pennsylvania). “I mean, we are funny.”

Social media offered a recuperating Fetterman a way to reach voters he wasn’t seeing in person or speaking to on television. In early June, Katz entered a campaign group chat to say Fetterman had made a “Running Away Balloon” meme in which Oz was reaching for the yellow orb labeled PA SENATE RACE but was being hugged by the pink blob labeled LIVES IN NJ. Hebert remembered thinking, “Wait, John can do graphic design? The candidate himself is making a meme …” The campaign tweeted it out.

Two days later, Fetterman had another idea, in response to news that Oz had spelled the name of his purported Pennsylvania hometown incorrectly on his candidacy statement. (It’s Huntingdon Valley, not Huntington.) This time, Fetterman’s chosen meme was Steve Buscemi’s 30 Rock appearance as an old guy pretending to be a teen, with the caption, HOW DO YOU DO, FELLOW PA RESIDENTS?

When that one took off, it became a free-for-all among campaign staffers. “It created this fun atmosphere,” said Hebert. “John’s rule for it was basically: Be funny, but don’t be mean.” “Especially after nearly dying,” Fetterman said of that distinction, “I had no malice in my heart.”

Almost everything would be run past the candidate; several staffers told me the highest praise you could get was “Oh, hell yeah, that’s a good one.” So the campaign spent a summer that otherwise felt very bleak trying to impress their boss and one another with new ways to dunk on Dr. Oz. “I always say that politics would be completely unbearable if there was no fun in it,” Gisele told me. “It would just completely suck. I need joy in my life — bread and flowers.”

All that joy turned out to be brutally successful. At one of the pinnacles — in which Jersey Shore star Snooki read a Cameo about Oz’s New Jersey roots — the Twitter campaign was highlighted on The View; as co-host Ana Navarro pointed out, “We’re talking about this on national TV. The reason is because it’s so effective … and it’s hilarious.”

The stroke-victim candidate forced off the trail by recovery had increased the likelihood that even the most indifferent Pennsylvania voter knew that Oz lived in a New Jersey mansion — in other words, that he was an elite, out-of-touch carpetbagger. The purity of the message was a lesson in defining your opponent. “I think a lot of people saw a Democrat who was flipping the script and going on offense,” said Calvello, “but not in a poll-tested way. We were doing it his way.”

It helped that Oz made himself such an easy target. The most notorious disaster was a video shot in a Redner’s grocery store in which he got the name of the store wrong and kept complaining about the cost of “crudité” — to which Fetterman responded, “In PA, we call this … a veggie tray,” triggering what the campaign said was a $500,000 windfall in donations. Oz also erred in trying to fight memes with memes, tweeting a poorly Photoshopped image of Bernie Sanders and Fetterman together along with the phrase “Best friends.” The deputy campaign manager jumped in with a response: “Graphic design is my passion.”

Fetterman said his campaign took care to use Oz’s “own words, his own videos, and his own material, to just be like, ‘Don’t take my word for it, here’s his.’” Multiple staffers remembered the day a communications aide noticed that Oz had filmed a campaign video from a library that looked suspiciously like the one featured in a 2020 People magazine spread about the doctor’s six-bedroom, eight-bathroom New Jersey mansion. “We had everyone poring over it,” recalled Hebert, all trying to prove it was the same place. Sure enough, Oz really had filmed the ad from his home in a state that is not Pennsylvania.

After the crudité video went viral, Oz’s campaign turned ugly in a way that would bring some of the summer’s social-media highs to a close for the Fetterman campaign. Oz’s communications adviser, Rachel Tripp, responded to the veggie-tray quip by saying, “If Fetterman had ever eaten a vegetable in his life, then maybe he wouldn’t have had a major stroke and wouldn’t be in the position of having to lie about it constantly.” Oz would wind up distancing himself from the line, but it sowed the seeds for how he would seek to redefine an opponent with a reputation for authenticity, strength, and relatability: to treat him as an enfeebled dissembler.

By mid-August, right-wing money was flooding Pennsylvania’s airwaves, and the starker realities of having a Democratic candidate who had been doing virtually no public events, interviews with the press, or in-person fundraising were sinking in despite Fetterman’s own TV ads. Some polls showed his double-digit lead shrinking to as low as a five-point spread. The campaign, which knew the race would tighten as November approached, had a new trace of anxiety in its swagger.

Fetterman started holding rallies and, especially in his early forays, made verbal stumbles that found their own damaging life on Twitter. The willingness with which the political press took up the frame offered by the Oz campaign has been startling, including the Washington Post’s editorial board proclaiming that “lingering, unanswered questions about his health” were “unsettling.”

Lack of transparency about a health condition would be unsettling, except that there has been ample coverage of Fetterman’s A-fib, cardiomyopathy, thrombectomy, pacemaker-defibrillator, weight loss, and auditory-processing difficulties. His campaign also disclosed that he’d taken two neurocognitive tests, both of which, it said, fell into the normal range. Every week since he reemerged, Fetterman’s public engagement has increased, and nothing about his increasingly frequent rallies and media interactions appears to be at odds with what doctors suggest would be normal for a 53-year-old four months out from a serious stroke and expected to make a recovery. There’s no great mystery about whether or how well Fetterman can speak: You can watch him do so regularly on television. There is also no open question about whether he can quickly process what he hears: He cannot do that well yet, which is why he requires closed-captioning for interviews and the upcoming debate.

At one point, when we were talking about his work to address crime and gun violence while mayor of Braddock, Fetterman said what sounded like a nonsense word. “To have an actual domicated — ” he paused. “Excuse me, domentated — ” He paused again, getting frustrated. “Yeah,” he added with a small smile, “this is the stroke right here.” Then he took a breath. “Documented,” he said. “Documented.”

Our 50-minute conversation, in which I could see his eyes moving swiftly across his computer screen as he read and responded to my questions in real time, included moments like the above, where it was clear that Fetterman’s vexation amplified his communicative challenges. Then he would relax and speak easily and without hesitation until the next expressive bump came.

Yet legitimate newspapers are pushing for further documentation with some of the energy once applied to Hillary’s emails, while the right-wing carnival barkers treat complete medical records as they did Obama’s birth certificate. The latter have taken cues from the Oz campaign — which in August sent out a doctored image of an overweight, shirtless Fetterman splayed above the messages “FETTERMAN IS A FRAUD” and “John Fetterman hasn’t attended a public campaign event since May 12” (the day before his stroke) and “Text ‘Lazy’ to 26771” — to depict the Democrat as a weak, shiftless liar.

Oz has been mealymouthed about abortion and has not gone after Fetterman’s labor-oriented agenda, instead trying to paint his opponent as a soft-on-crime Democrat. It’s a surprising choice given that Fetterman’s political origin story involves his moving to Braddock, after an upper-middle-class upbringing, to run a youth GED program, then run for mayor out of a desire to bring down gun violence. He regularly notes that during his mayoralty, there were five years in which no one in Braddock was killed by a gun.

Oz has nonetheless mounted an offensive singling out Lee and Dennis Horton, Philadelphia brothers who spent 27 years in prison for a murder they didn’t commit. A short documentary about the brothers, highlighting their immaculate record and years of community work inside prison, won a regional Emmy this year. After pushing for their release as lieutenant governor, Fetterman hired them to work on his campaign; Oz has called for him to “fire convicted murderers.”

Fetterman is clearly furious about the right’s assault on the Hortons and his work on the clemency board, which has been juiced by the Senate Leadership Fund super-PAC, though he told me he knew it would come. “Before or after the stroke,” he said, “I’m smart enough to realize that if I fought to free two Black men with the last name Horton, that is going to go ding ding ding” for future Republican opponents, a reference to the attack ads on William Horton that helped to sink Michael Dukakis’s 1988 presidential campaign.

And indeed, the right is all in. Donald Trump Jr. recently retweeted an image of a truly bonkers “soft on crime” billboard the Oz campaign has erected in Braddock: It shows an image of a little girl holding a puppy in what looks like a toilet-paper ad next to one of Fetterman making a weird face; the captions SOFT ON BOTTOMS, SOFT ON SKIN, and SOFT ON CRIME run underneath them. Meanwhile, Newt Gingrich has suggested that one of Fetterman’s tattoos — nine of which are the dates of death for Braddock residents who died violently during his mayoralty — is “a tribute to the Crips.”

The inversions and ironies are mind-boggling. Oz, a man who came to politics after having been questioned on the Senate floor about making unsubstantiated claims regarding “miracle” weight-loss pills, is framing Fetterman as less than medically forthcoming. Oz, who built a daytime-television empire thanks to Oprah Winfrey and by telling women it’s bad to be fat, is feminizing Fetterman and shaming him for being lazy and overweight. Oz, whose medical research led to Columbia University being fined for cruel experimentation on and the deaths of more than 300 dogs, is running a billboard using the image of a little girl and a puppy to cast Fetterman as some sort of deranged pansy, while repeatedly calling him “pro-murderer.” (In response to a query about the dogs, Oz’s spokesperson said, “Suppose you were the dumbest person in the world. Now suppose you were a reporter for New York Magazine. But I repeat myself.” He did not deny the allegations about the puppies.)

None of it makes any sense unless you understand that this jumble of references and images is meant to invoke emasculating and racist tropes. Those tropes remain so endlessly seductive to the American electorate and its mainstream media that the right will return to them even when the candidate it’s battling is one of the biggest, whitest dudes you’ve ever seen.

My brother is a big white man with a bald head and a beard, like John Fetterman. He maybe doesn’t always eat carefully or go to the doctor enough, like John Fetterman. The child of middle-class cultural privilege, like John Fetterman, he has an associate’s degree from Community College of Philadelphia, is a walker of big dogs, and coaches boxing to kids in his Philadelphia neighborhood to help keep them busy and safe after school — a profile that is different, but not so different, from John Fetterman’s.

My brother is a committed feminist who cares a lot about the future of the planet and criminal-justice reform. In other words, he cares a lot about the outcome of this race. And he had a much harder time than I did watching Fetterman speak at a rally in Montgomery County one rainy Sunday in early September. This gathering had been unwisely scheduled during the Eagles’ season opener in one of the crucial suburban counties that collar Philadelphia; driving over, we had wondered whether anyone would show up at all. But when we pulled into the parking lot, a line was snaking around the building. More than 3,000 people had stood for more than an hour in the drizzle, and hundreds had to be guided to an overflow room. Before the event, Fetterman mingled with those who weren’t going to make it inside the gym; he made eastern and western Pennsylvania jokes about Wawa and Sheetz, Eagles and Steelers, as people in the crowd vibrated with excitement and a couple actually cried, the way you do when you meet a larger-than-life celebrity. A celebrity you’re rooting for very, very, very hard.

The rally’s theme was reproductive health care, and Fetterman was the only man speaking that day alongside Planned Parenthood head Alexis McGill Johnson. After Gisele introduced him, Fetterman strode slowly to the podium to face the pounding applause. He stretched out his arms in a gestural embrace, placed one of his big pawlike hands on his heart, and stretched out his arms again, holding in one hand a piece of bunched hot-pink fabric.

“My name is” — a millisecond pause created the tiniest frisson of tension (was he going to have trouble with his own name?) before he unfurled that pink T-shirt and said — “John Fetterwoman!”

An enormous cheer of amusement, relief, and a desperate yearning for his speech to go well came up from the crowd.

I thought it went well; he did fine and appeared noticeably more hale than he had in clips that were circulating derisively around Labor Day just a week earlier. But afterward, my brother told me how scared and uncomfortable he felt bracing for a possible tangle of words or any pause that stretched an extra beat, worried that it would wind up as right-wing fodder. I wondered if my job, which has involved sitting exactly that way through every public appearance of the women in politics I’ve covered — understanding that any single slip or weird facial expression would be used to make them look weak or radical or dishonest or unhinged or stupid — had inured me to that feeling of raw and relentless exposure. My brother, perhaps like Fetterman, isn’t used to it.

It’s a precarity that millions are feeling this year in the wake of the Dobbs decision. Pennsylvania, like other states, has seen a surge of women registering to vote: Over the summer, 56 percent of new voters have been women, compared with 44 percent men, a gender gap reportedly three times its typical size.

Fetterman has been good on abortion since before the Supreme Court struck down Roe. Back in 2016, he said the thing you’re not supposed to say out loud — that he would impose litmus tests on judicial nominees over whether they support abortion rights. He supports ending the filibuster, in part so the Senate might codify Roe. Since his return to the trail, he has offered a contrast to the hand-rubbing glee with which some Democrats have met the prospect of a post-Dobbs, pro-choice voting surge. Asked by MSNBC’s Alex Wagner if he saw Dobbs as “a gift to Democrats,” he replied, “I don’t consider it as a gift. It’s actually a very dangerous kind of law.”

At the Montgomery County rally, which was crowded with women wearing shirts reading ROE-VEMBER, ELECT WOMEN, and I’M WITH GISELE’S HUSBAND, a 35-year-old supporter named Amanda addressed this dynamic bluntly: “Unfortunately, it’s what we learned from Hillary Clinton.” In a follow-up email, she clarified that “our country has found itself in a position where most people feel more comfortable placing their trust in a straight white man.”

Jessica Klemens, a Montgomery County OB/GYN who is part of group of doctors organizing for Fetterman and the Democratic gubernatorial candidate, Josh Shapiro, told me with a dry laugh that her neighbor Val Arkoosh, a physician and political moderate who had run against Fetterman in the primary but dropped out early, “was going to be our first woman senator from Pennsylvania, right?” But Klemens is now an enthusiastic Fetterman supporter, and Arkoosh herself was speaking at the rally.

Klemens introduced me to her mother, Lorraine Mory, a nurse and Evangelical Christian who has always voted Republican, “pretty much as a single-issue voter: against abortion rights,” she said. But Dobbs and her daughter’s work changed her mind. Mory and her husband had recently moved to Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley after the passage of an anti-abortion trigger law in Tennessee. “I’m not saying that was the reason we moved,” she said. “But it certainly is a contributing factor; my vote didn’t count for anything in Tennessee.” Now, they had contributed to Fetterman’s campaign and were planning to put up a lawn sign.

In the final weeks of the race, Oz is playing both sides of the crime issue. While Republicans are running soft-on-crime attack ads in certain parts of the state, in the Philadelphia market, where Black voters are a crucial part of any Pennsylvania Democrat’s path to victory, other spots highlight the notorious incident in 2013 in which Fetterman brandished a gun at an unarmed Black jogger, for which he was hit hard in the Democratic primary. (Fetterman has maintained that he did not know the race of the jogger and that he chased him after hearing gunshots, though the jogger claims the sound was made by bottle rockets.) Oz’s team has also kept up its mocking posture on his opponent’s health. After Fetterman committed to a debate, Oz spokesman Keller said to Politico, “Is it possible to quote somebody laughing?” When I questioned Keller about that line, he said, “Our campaign told him to eat his vegetables; his campaign hired two convicted murderers.”

Fetterman is working to maintain his aggressive approach. On October 3, he tweeted out a Washington Post investigation into the history of questionable medical products promoted on Oz’s daytime talk show and commented, “Dr. Oz got rich + famous from ripping people off. He is not just a phony + a fraud, he is a malicious scam artist who knowingly hurt regular people to line his own pockets.”

But while the image of Fetterman as fighter is what his campaign is going for, it’s possible that it is benefiting from a more complicated dynamic: that over the course of the race, Fetterman has become even more familiar to voters, not because of his Everyman toughness but because of his struggles.

“Before the stroke,” Fetterman told Alex Wagner, “I thought I was a very empathetic person and I really understood what it was like for people dealing with these kinds of challenges. But this has made me ten times more empathetic.” Some swing voters in focus groups have returned that increased empathy in kind, talking frankly about how they haven’t always listened to their doctors, how their husbands have had similar strokes, and how they remember what it’s like to recuperate from a health challenge.

“I haven’t had the opportunity to process the trauma of not realizing if you were going to survive or what your future was,” Fetterman said. “I haven’t had the opportunity because I had to learn how to hear myself speak again. Physically, I was fortunate I was able to walk and drive and all those things, but in terms of my ability to hear things and be able to speak and understand what’s being said — that is something that I had to work through. I certainly would never have remained in the race if the doctors or my family felt I had some sort of issue and if I wasn’t able to progress through the summer. But I was able to get better and better and better.”

Watching him on that road to recuperation is really nervy, really scary for those who understand how much is riding on this race. But every week, he makes fewer mistakes, stumbles a bit less, and gets clearer and more relaxed. Voters have been knocked flat by a pandemic, by Dobbs, by storms and mass shootings and rising prices — by reckoning with it all — and the vision of a human being who has also been knocked flat making his way back toward health along an unlikely and precarious path is very powerful. As Gisele says she tries to teach their children every day, “Nothing is the end other than death.”