On a matter so fundamental as the long-established federal constitutional right to an abortion, you’d like to see some clarity in legal battles. Until the Supreme Court order in Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson last week, it had been widely assumed we’d get some direction next spring when the Supreme Court decides Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, a challenge to a straightforward effort by Mississippi to seek a reversal of Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which would return abortion law to the tender mercies of state governments.

But following the Supreme Court’s action on the Texas case, we are now in murky and uncharted waters legally. At the moment, there have been none of the private lawsuits that the Texas law (SB 8) relies on to enforce a ban on abortions after six weeks of pregnancy, and thus, under the Court’s order, there is no way to enjoin implementation of the law. But that is, in no small part, the result of abortion providers choosing to comply with the law, fearing the great risks and enormous costs that could ensue from becoming the first target of potentially endless litigation.

At the moment, then, anti-abortion activists and their Republican servants are getting what they wanted in creating this deviously complicated system, even though the five-justice majority in Jackson went out of its way to disclaim any judgment on SB 8’s constitutionality. That probably explains why the bravos of the anti-abortion movement have refrained from echoing the intense reaction of their pro-choice opponents to the order: The nothing-to-see-here language of the Jackson order serves their purposes. They have every reason, moreover, to expect that the same five justices (perhaps joined by Chief Justice John Roberts) will administer the coup de grace to abortion rights in Dobbs, at which time their rejoicing will be open and their persecution of abortion providers and the women who rely on them will be right out of The Handmaid’s Tale for real.

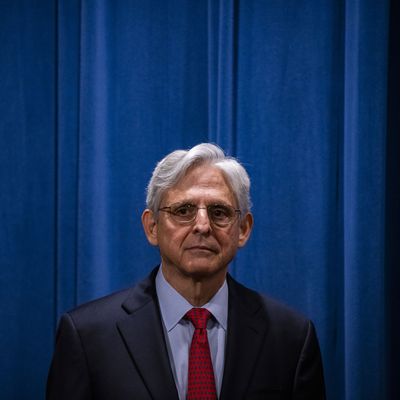

In the meantime, it’s hard to predict what will happen. Amidst the great outcry of fear and outrage from reproductive-rights advocates, theories for how the Texas enforcement scheme can be thwarted with the federal courts refusing to put it on hold are popping up in every direction. President Biden vociferously but vaguely promised a “whole of government” effort to defend abortion rights in Texas. Attorney General Merrick Garland rattled his saber publicly, telling reporters he had reached out to U.S. Attorneys’ offices and FBI field offices in Texas and across the country to “discuss our enforcement authorities.” He specifically mentioned the FACE (Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances) Act, a 1994 law allowing for federal intervention to protect abortion clinics from violence and other forms of harassment, which was probably a brushback pitch to ensure anti-abortion activists don’t supplement the threat of private lawsuits with more direct form of intimidation.

Retired Harvard constitutional law professor Laurence Tribe took to the op-ed pages of the Washington Post over the weekend to suggest the Justice Department utilize provisions of the Enforcement Act of 1870, which made it a crime for anyone acting under a government authorization (in legal jargon, acting “under color of law”) to deny constitutional rights to others. A parallel provision imposed criminal penalties on anyone, with or without government authorization, who acted in concert with others to deny constitutional rights. These legal powers were aimed at white terrorists battling Reconstruction in the South, and were revived by prosecutors and judges during the Civil Rights era to provide a weapon against the white terrorists of that day.

Other legal beagles have pointed to a separate Reconstruction law giving private parties a civil right of action against those acting “under color of law” who deny constitutional rights: It’s the law that made it possible for the family of George Floyd to sue the Minneapolis cops involved in his murder and the city that employed them.

Any of these strategies, of course, will be contested by Texas, and will lead to additional litigation, whether or not the federal courts continue to reject a more direct challenge to SB 8. Sooner or later, the question of whether constitutional rights are in fact being thwarted by SB 8 will become unavoidable, in which case the five-justice majority that generated this crisis will have to decide whether to (a) go ahead and address the constitutional issues raised in Dobbs ahead of schedule; (b) apply the precedents currently in place and gut SB 8; or (c) go in some wholly unexpected direction. In the meantime, there are already signs other Republican-controlled states will enact copycat laws duplicating SB 8, creating a de facto post-Roe regime in significant parts of the country until such time as federal courts find a way to authorize challenges (such as those Garland is contemplating) to such laws, or validate them retroactively with a direct strike on abortion rights. It’s going to be a wild and perilous ride over a dark, rocky, and sinister landscape.