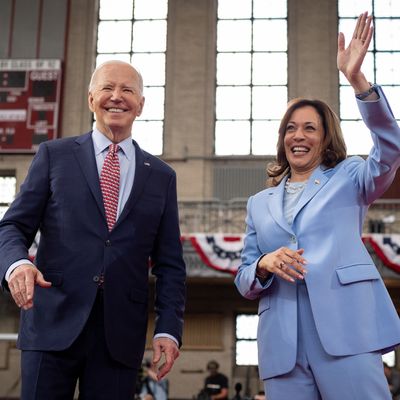

Sometimes in politics, a perfectly justified maneuver falls to the wayside because there’s no way to execute it. Justified or not, the scheme to replace Joe Biden and Kamala Harris with a wholly new Democratic ticket will fail because no one is in a position to make it happen.

My esteemed colleague Jonathan Chait makes a solid, if not incontestable, case that there are stronger options than a 2024 Biden-Harris ticket, or a replacement of the president by his vice-president, for what has now become a desperate fight to keep Donald Trump out of the White House. He argues that the reluctance of Democrats to toss the incumbents and start over represents a sort of failure of nerve induced by Biden’s stubborn selfishness and Harris’s weaponization of identity politics:

At the moment, according to one post-debate poll, only 27 percent of Americans believe Joe Biden has the mental and cognitive health to serve as president. This poses an almost-insurmountable obstacle to his election, even with Trump’s manifest unfitness. Biden is losing, and he has already squandered what his own campaign considered his best chance to change the race.

Again, even with all her limitations, Harris is probably a stronger candidate now than Biden. I also think there are better options than Harris.

Democrats, Chait believes, can seize the opportunity presented by Biden’s debate debacle to make a fresh start, if only they show “the collective willpower to make political choices in the clearheaded interest of their party and their country.”

I have mixed feelings about my colleague’s assessment of the political situation. But about this I have little doubt: At this late date, there is simply no instrument for canceling or reversing all the decisions the Democratic Party has made over the past four years. There is no way to muster the collective judgment of Democratic voters about an ideal 2024 ticket. The primaries are long past; every single potential Biden or Harris rival has already bent the knee to the reelection effort; the soon-to-arrive convention’s only conceivable managers are in the White House or in the Biden campaign; and, even if there was agreement among Democratic elites and rank-and-file party activists that Joe must go and take Kamala with him, there is no consensus on replacements. Chait likes the idea of a Whitmer-Booker ticket; dozens of other ideas would arise if the party was somehow forced to upend primary voters and pledged delegates and start anew. Who, specifically, will forge the consensus? Nobody comes to mind. How, mechanically, would it be imposed? It’s very hard to envision it occurring without magic far more fanciful than Biden and/or Harris picking up a few points to beat Trump in November.

Let’s be clear: There’s no template for what the would-be deposers of Biden and Harris are suggesting. The last major-party convention in which there was any doubt about the outcome was the Republican confab of 1976, which was in turn the product of two candidates slugging in out to a draw in the primaries. Both were battle tested and could claim a popular mandate. The last multi-ballot convention was the Democratic gathering of 1952, which produced a landslide losing ticket. You have to go back to the Republican convention of 1940 — 84 years ago, long before the era of universal primaries and caucuses — to find a convention that suddenly chose a dark-horse nominee because he seemed a better bet than the career politicians he shoved aside. That nominee lost too. And the last truly wide-open convention was exactly 100 years ago, when Democrats took 103 ballots to nominate a candidate who won a booming 28.8 percent in the general election. Open conventions always sound like fun to political pundits. They are a disaster for political parties, particularly parties in mid-panic.

As it happens, the timetable for blowing up a settled nomination is particularly poor right now. Because of an Ohio ballot deadline, the Democratic National Committee has already decided to hold a “virtual roll call” for the presidential and vice-presidential nominations more than a full week before the convention begins. The idea, of course, was a pro-forma ratification that at most might represent a campaign infomercial. Is it now to become a deliberative and likely multi-ballot process that delegates enter with no idea of the outcome? That sounds like true chaos. And the only thing that could make it worse is an endless series of behind-the-scenes meetings where Democrats — which Democrats? Delegates? Delegation leaders? Party pooh-bahs? Donors? Interest-group leaders? The Clintons? The Obamas? — struggle to agree on a ticket.

Yes, there are reasons to worry about Biden’s capabilities as a candidate going forward and reasons to fear that Kamala Harris isn’t an ideal presidential candidate either. But the evidence is very mixed. If in a week or so that evidence turns unambiguously dark, the extremely efficient course for Democrats is the one Republicans chose in 1974 when congressional leaders of unimpeachable loyalty to Richard Nixon went to him and convinced him to throw in the towel. Another colleague of mine, Gabriel Debenedetti, says that the 46th president may not want to listen. But it’s the best bet for changing the ticket and eliminating the immediate source of panic. Indeed, it would be an important and appropriate consolation prize for Biden that as he “stepped aside” he would name a successor. The party could unite around this candidate and be spared the impossible chore of letting the ticket be chosen by pollsters for the benefit of politicians who did not enter a single primary. That successor will very likely be Kamala Harris, and she’s not ideal. But ideal presidential candidates do not fall from the sky or ascend via a landslide among opinion columnists.