A specter is haunting the Republican Party. And that specter, oddly enough, is a future world in which Republicans control government and pass bills that they campaigned on.

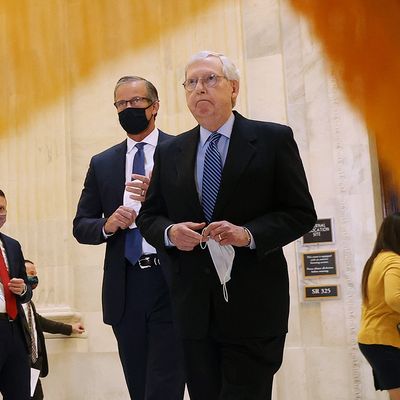

Mitch McConnell’s latest defense of what remains of the filibuster yesterday veered wildly between two irreconcilable claims. On the one hand, he warned a majority-rules Senate would be a “scorched earth,” “disaster,” “hundred-car pileup” in which nothing happens. On the other hand, he warned that once Republicans gained control of government, the chamber would become a smooth-running machine in which conservative priorities are quickly enacted.

Here is McConnell’s complete account of the horrors that await the country were the legislative filibuster to perish:

“As soon as Republicans wound up back in the saddle, we wouldn’t just erase every liberal change that hurt the country. We’d strengthen America with all kinds of conservative policies with zero input from the other side. Nationwide right-to-work for working Americans. Defunding Planned Parenthood and sanctuary cities on day one.

A whole new era of domestic energy production. Sweeping new protections for conscience and the right to life of the unborn.

Concealed-carry reciprocity in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Massive hardening of security on our southern border.”

The Wall Street Journal editorial page, echoing McConnell (as it usually does) chimes in: “Republicans would be in position to rule the Senate without a filibuster. Imagine what they might pass? Mr. McConnell gave a few examples — defunding Planned Parenthood — but for political flavor think GOP Senators Josh Hawley and Rand Paul unbound.” This, as we’ll see later, is telling.

McConnell has made gridlock so routine that both he and his imagined audience see the idea of a party enacting the proposals it advocates as fantastical and scary. But if you go to any of the 50 states, that is not how political rhetoric operates. Candidates for office advocate positions, then try to pass them into law when elected, and take credit for them if they work. The opposition party either accepts those changes, modified, or runs against them and tries to reverse them if they remain unpopular. Likewise, every democratic government in the world that I’m aware of operates on the same principle.

None of these democracies, domestic or foreign, needs a supermajority to protect against an elected government carrying out its promised agenda. Obviously, temporary majorities need some restraint to prevent excess. But those restraints exist — in the American system, not only multiple veto points and courts that can curtail unconstitutional laws, but democracy itself. The dynamic that inhibits majorities from exceeding their mandate is the prospect that their policies will create a backlash and be subject to reversal.

In place of this, we have the peculiar dynamic in which the leader of a major party is invoking his own agenda as something that cannot and should not happen.

Obviously, I don’t like the policies McConnell described. What I can’t understand is how McConnell is supposed to feel about them. If he truly thinks they’d “strengthen America,” then shouldn’t he want to have the chance to enact them, and then have his party run on the results?

Democrats think of their agenda this way: They believe their policies would prove popular if enacted. Republicans might think they’ll hate them, but once they have seen them in action, they’ll come to realize those policies make most people’s lives better. Nancy Pelosi’s frequently mocked line about Obamacare (“We have to pass the bill so that you can find out what is in it”) captured this idealistic belief. And her prediction was borne out — once Obamacare was up and running, people understood what it did and wanted to keep it.

The Journal’s version of a scary Republican government (“Josh Hawley and Rand Paul unbound”) is self-evidently preposterous — by definition, unpopular gadfly legislators don’t have the power to amass majorities in two chambers. McConnell’s list combines policies that the last GOP administration enacted without any input from Congress at all (“new era of domestic energy production,” “massive hardening of security on our southern border”) and policies Republicans would probably be unwilling to vote for (“defunding Planned Parenthood,” “sweeping new protections for conscience and the right to life of the unborn”).

Maybe I’m wrong about some of these items. Perhaps the next Republican government can pass a sweeping anti-abortion bill, presumably after the courts strike down Roe v. Wade. There are certainly a lot of conservative voters who desperately want this to happen. Has McConnell told them that the goal they have been pouring their hearts into is impossible, because of rules McConnell is fighting to keep in place? I can’t think of any way to read his comments other than a backhanded admission that what the Christian right considers the murder of the unborn cannot be stopped unless the filibuster is defeated.

Obviously, McConnell would never concede this openly, even though it follows straightforwardly from his logic. His agenda exists in a netherworld where one group of people is told it will happen if they vote Republican, and another group is reassured it never will.

This kind of doublethink is a product both of the unique supermajority requirement in the Senate and the Republican Party’s retreat from serious governing. Conservatives are increasingly unable to conceive of legislation as anything other than a zero-sum exercise in punishing and humiliating the other party. They imagine Democratic laws are merely pretexts to expand government power, and then internalize the same logic for their own agenda.

McConnell benefits from rules that allow him to enact all the changes he cares about — lax regulation of business, tax cuts, and confirming judges — either with just the presidency, or the presidency plus a majority. He fears allowing his caucus to actually enact laws carrying out most of their promises. That is why the bogeyman role of Hawley and Paul is so revealing. They represent McConnell’s fear of having to translate conservative demands into concrete legislation. He’d much rather use the passions of his base to get elected, and then use that power for ends McConnell cares about.

That is McConnell’s problem. How much sympathy he deserves is a matter of personal taste. But why should his travails dictate the workings of a great democracy?