Jenny Davidson, 49, understands that what she is about to do will make people angry. On Monday, January 11, she read on a listserv of fellow English professors at Columbia that Phase 1B in New York’s vaccine scheme, opened up that very day, would include “in-person college instructors.” Davidson is teaching remotely this semester, but someone on the list had talked to a lawyer, which left the professors convinced that all college instructors could theoretically be teaching in person, especially if they got vaccinated.

Davidson was, at that moment, in the Cayman Islands, where her partner lives. (She says she followed the strict quarantine rules, which include a government-issued tracking bracelet.) “I thought, Do I feel amazing about this? No, but I also don’t feel like a total weasel because I am going to do in-person things with the students,” she told me, such as meeting indoors in small groups, masked. That afternoon, after some thought, she decided to “not dither on this.” To her surprise, when she logged onto the New York City appointments site, she still had her pick. It was the first day that appointments had been available to anyone but health-care workers and people in long-term care facilities.

She chose one on the 22nd, in the Bronx, because it was relatively convenient to get to. A couple of hours later, she posted about it on Facebook. “I am not saying that I think this fair or right,” she began, “but yes, PSA for NYC academic colleagues.”

When one of her friends replied, “Having consulted w friends in public health and city govt, I have concluded that we (professors) do not need to feel guilty about availing ourselves of the opportunity to get vaccinated now. Doses are going unused. At this point, simply getting more people vaccinated is a priority. My delaying does not mean that someone else (e.g., K-12 teacher) will get vaccinated sooner,” Davidson responded, simply, “yes.”

The days earlier had been full of headlines about a disastrous rollout: Vaccines were sitting in freezers, unused, because as many as a third of health-care workers who were eligible were turning them down, or worse, defrosted doses were being flushed down the toilet because Andrew Cuomo was going to fine them up to a million dollars if the vaccine ended up in the wrong arm. On January 8, the New York Times reported on a Harlem nurse who “set out on foot” to find people she was allowed to vaccinate after people didn’t show up for appointments, but was forced to throw away four about-to-expire doses; a hundred blocks south, the medical director of the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center, who was somehow given 600 doses he didn’t need for his staff, was desperate to vaccinate his patients. The day of that Times report, only 34 percent of New York City’s vaccines were being used, below the state average.

A durable narrative soon took hold. Rushing to sign up for a vaccine, even if you didn’t otherwise qualify or were able to stay home, was the right thing to do, because they were going to waste. The sign-up process was an abject disaster; the government had been fumbling for 11 months; the death count was rising; why not take matters into your own hands to protect yourself and others from this horrible disease? Especially when eligibility seemed so arbitrary. “I am 63, and I have asthma and a tendency to pneumonia and am pretty sure that if I get it, I will either die or be compromised for the rest of my life,” Claire Potter, a professor at the New School, wrote in an email. “I think one of the things that pushed me over the edge is how bad the rollout is, and the news that they were throwing away spoiled vaccines because they didn’t have enough arms to put it in.” She signed up to be vaccinated on January 25.

“It’s an absolutely unacceptable, shameful thing, the prospect of flushing down the toilet a dose of COVID-19 vaccine,” says Ruth Faden, founder of the Johns Hopkins University Berman Institute of Bioethics. “It’s horrifying. How much has it happened, I have no idea. Makes for a great story.”

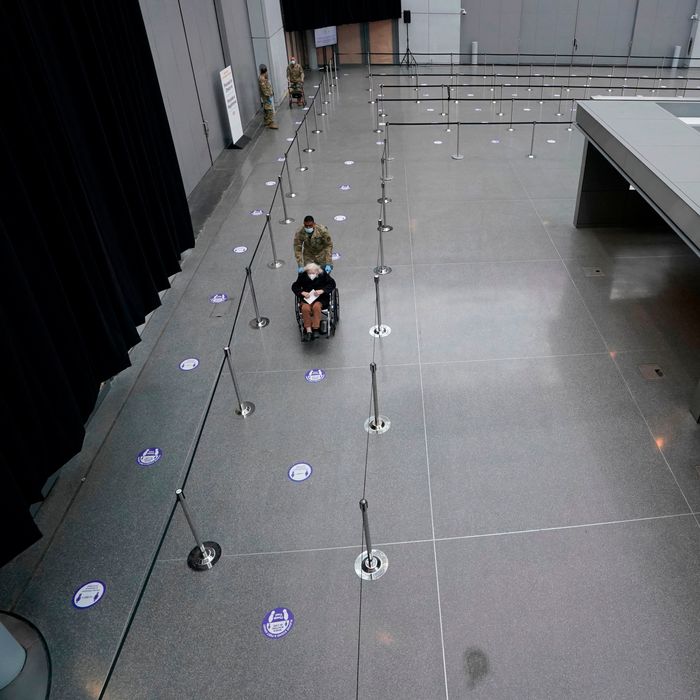

However many times it happened, it’s unlikely to be happening now, at least in New York, where, on January 14, a couple days after Davidson made her appointment, 500 people stampeded to the Brooklyn Army Terminal on the thinnest of intel that vaccines were about to go to waste. Public outrage over a backlog forced Cuomo to open up vaccine eligibility to everyone over 75 and certain work categories; the next day, federal guidance changed again, expanding eligibility to everyone over 65 and to “the immunocompromised” — itself a murky category which the state has yet to define. According to the state, rapidly opening up the gates means New York has about 250,000 vaccines a week for 7 million currently eligible people, and the supply from the Feds actually had actually gone down by 50,000 from the week before. “Only Jesus with the loaves and fishes could handle the situation that the federal government created,” Cuomo grumbled Wednesday. “Because they created such a demand and they never increased the supply.”

New York City has, as of this writing, used 90 percent of its stockpile, according to the state’s COVID-19 vaccine tracker, and 91 percent has been used statewide. After Mayor Bill de Blasio warned Tuesday that the city was going to run out of vaccines, the city’s health department started rescheduling people — including Davidson — with end-of-week appointments, for next week’s reup. And that’s if you can even figure out how to make one in the maze of local and state and medical and pharmaceutical appointment systems.

That not everyone would have the same ease of making an appointment as Davidson soon became clear to her from her Facebook feed. “When I saw how upset people were, I felt bad about it,” Davidson said. Some of her friends have children in remote schooling and hope that vaccines for teachers — K-12 ones — might mean their kids will get to see the inside of a classroom soon. Some are trying, and failing, to get their elderly parents appointments, even after hours of effort from educated and system-savvy people. Some are facing both.

But she isn’t sorry, and she was happy to talk to me about why she signed up: “I didn’t want to make this choice and conceal it.” Davidson reasons that speeding up herd immunity and the benefits to her students justify the liberal reading of the guidelines. An op-ed over the weekend by Zeynep Tufekci arguing that “we should focus on speed and access, not on punitive efforts to ensure strict adherence to complicated eligibility rules” cemented her resolve. Indeed, in the absence of any national distribution plan, who gets the vaccine when can be absurdly arbitrary. Take Davidson’s own mother. She’s 78, but she isn’t currently eligible for a vaccine under the current rules, because she lives in Pennsylvania.

Says Davidson, “I really do believe in getting vaccines in arms.” So why not her own?

Moral reasoning in a time of scarcity, when the medical system is buckling and so far no one has been in charge, makes for murky decision-making. Call up a bioethicist or two, as I did, and they’ll tell you the problem is so much bigger than any one person’s choice, or any particular group reading the rules in their favor. “I don’t like it, but I understand it,” says Arthur L. Caplan, a professor of bioethics at NYU. For one thing, the rules were confusing to begin with. “You tell me what the restrictions are, don’t make me guess,” he said. He also wishes authorities would offer clearer guidance to vaccinators on how to use whatever they have left over.

The irony of all this maneuvering is that public-health experts spent many hours developing prioritization schemes to avoid the most privileged people being able to game the system, only to heighten the effect with more complexity. “We have to be thinking again, maybe we made things over-complicated and didn’t match up with our good intentions,” Faden, of Johns Hopkins, said. “These carefully calibrated vaccine groups are collapsing under their own weight.” Faden pointed out that in Israel — which has already vaccinated 35 percent of its citizen population — simplicity helped: Eligibility went by age.

Faden has argued that vaccinating K-12 teachers first is more important than professors — like her — because children and younger teens are harmed more by digital schooling. “Their life trajectories could be sent in a different path. Young adults who are also at risk can be more resilient,” she told Inside Higher Ed. Still, she said gently when I pressed her on the college instructors, “You have to think about where you have to focus your moral energy.”

Faden worries that the people who hesitated early on — medical or long-term care workers who were suspicious of the vaccine or who were otherwise unable to book an appointment — will be left behind now that the policymakers have quickly moved on.

“I talked to a CEO of a very small rural hospital and that person figured out pretty early on that some of their sanitation staff and food-service staff couldn’t manage the system that had been set up,” she said. In order to make vaccine appointments more accessible, the hospital tasked direct supervisors with helping their teams get vaccinated. Faden wants to see more of that.

Similarly, universities aren’t only made up of white-collar workers. CUNY’s faculty and staff union, which advocated for their members to be included in Phase 1B, nonetheless reminded its remote-work members in an email “to be mindful of the urgent need for in-person workers both at CUNY and throughout the state to have access to vaccination now. Phase 1B includes many of the occupations with high risk of exposure in which our students and their families often work: public transit, child care, health care, and grocery stores.” (My husband is a member, currently on sabbatical).

Munira Ahmed’s grandmother is the type of person people fret will get left behind: She’s 88, an immigrant from Bangladesh, and doesn’t have an email address. What she does have is a 36-year-old granddaughter. Last week, Ahmed’s mother sent her a link on WhatsApp to the New York City signup page and asked her to check it out.

“You have to use your email address, and each email address can only register for one individual,” Ahmed said. Figuring she would learn the ropes for her grandmother, Ahmed answered all of the questions about herself: that she lives in New York City (Jamaica, Queens), that she isn’t an essential worker (she works in business development). The questionnaire didn’t ask her whether she’d had COVID, which she did back in November, after her mother ate inside a restaurant on Long Island. Her mother, severely ill, was hospitalized and still takes antibiotics from lingering symptoms. Ahmed and her sister rode out isolation with relatively mild cases, though as we spoke, “COVID fog” overtook her a few times.

On the New York City site, Ahmed kept progressing to the next step. “I was expecting it to say to check back in or that it would add my name to a waitlist,” Ahmed said. Instead, in an apparent glitch, she found herself on a page with a list of high schools administering vaccines and a calendar where she could make appointments, with available times. “I was like, holy shit. I selected it. There’s a page that says you agree that everything you wrote was true.” Everything was. “It was surreal. I couldn’t understand how I got an appointment.” She didn’t have time to think further; having grabbed an appointment for herself, she called her aunt to get her grandmother’s insurance information. Sure enough, using her work email address, she filled in her grandma’s information and was able to secure an appointment. “Until they figure out how to manage that better, then whoever has the time and energy and effort to go get vaccinated, should,” Ahmed told me. On the 16th, they got their shots. Ahmed says her family has been trying to spread the word, including at the Bengal senior center where her mother works. “Without them knowing firsthand that they know someone who’s vaccinated,” Ahmed says, “they might think it’s useless to even make an account.”

Ahmed and her grandmother will get their second shot on Valentine’s Day. Watching her grandmother get her first, Ahmed wept and asked the nurse for a tissue. All she had to offer was a disposable mask. Ahmed wrote on Instagram, “That’s 2021 for ya.”