This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

The revelation arrived on horseback.

One morning this winter while staying at the Ritz-Carlton, Dove Mountain, just north of Tucson, Arizona, Steve Schmidt was out riding. As he made his way along the desert path, he later recalled, his mind wandered and relaxed in a way he had experienced before only through meditation.

Schmidt started meditating after the successive health scares (a brain tumor followed by a fall from a different horse that resulted in a broken back, he said) that led him to get Cali sober, trade red meat for salads, start exercising, and lose 50 pounds. Yet the more he solved every problem he perceived to be within his control, the more it became obvious that mindfulness and wellness could not cure what he had identified as the biggest source of his unhappiness. He believed he had enemies, and he believed they were winning.

He had been “a celebrity” and “a famous person” since going to work for John McCain’s 2008 presidential campaign, he said. That came after working on George W. Bush’s 2004 campaign and in the White House, where Schmidt managed the Supreme Court nominations of Samuel Alito and John Roberts before heading west to salvage Arnold Schwarzenegger’s bid for reelection as governor of California. Of the ways that status had changed his life, he fixated not on the opportunities and wealth that had put the son of a schoolteacher and phone-company lineman from North Plainfield, New Jersey, on cable news frequently, made him buddies with Woody Harrelson (who played him in the HBO adaptation of Game Change), and parked a ’65 Corvette Stingray in the driveway of his 7,500-square-foot home, but on every hater in his mentions and every hater in the press and the hater he hated most of all: Meghan McCain.

He blamed her for, among other insults, leaking the news that, like Donald Trump, he had not been invited to her father’s 2018 funeral. And though many press accounts of the 2008 election told of Schmidt’s involvement in the VP-selection process, Schmidt considered Meghan McCain’s characterizations to be the primary reason anyone had the impression that he was to blame for the catastrophic decision to choose Sarah Palin as John McCain’s running mate. “There’s different versions of this story,” Meghan said in 2012, following the premiere of Game Change, “but Steve Schmidt and Nicolle Wallace were the people single-handedly responsible for finding Sarah Palin, and now they just trash her all day long, and they did not treat her with the respect that she deserved.” In 2021, after John Weaver — who, along with Schmidt, had co-founded in the Trump years the save-the-soul-of-the-GOP organization the Lincoln Project — was accused of initiating improper sexual communication with younger men to whom he had offered professional guidance and opportunities, Meghan’s public criticism sharpened. Her father had “despised” both Weaver and Schmidt, Meghan said in a tweet, and had personally banned both men from his funeral. “Since 2008, no McCain would have spit on them if they were on fire,” she said.

Schmidt came to perceive what he had endured in the 14-year period between the 2008 election and the collapse of the Lincoln Project as “abuse.” But not just that. He believed the wanton attempt to destroy his reputation had occurred in tandem with the decline of the Republic. His enemies, guilty as they were of committing acts of terror against him through what felt like a million petty, personal slights, were guilty, too, of precisely the sort of deceit and political corruption that was destroying America.

When he discussed these outrages, they were presented as intertwined. It was about truth, he said. It was about who defines it and who is victimized by those who distort it. If people are afraid to tell the truth in their own defense, then truth cannot exist anywhere. If you are going to fall for the big lie, or if you are going to watch in silence as it spreads, you first need to lose your faith in much smaller ways: to lose faith in yourself and in others, maybe, or to stop caring altogether. It was complicated, though Schmidt didn’t see how.

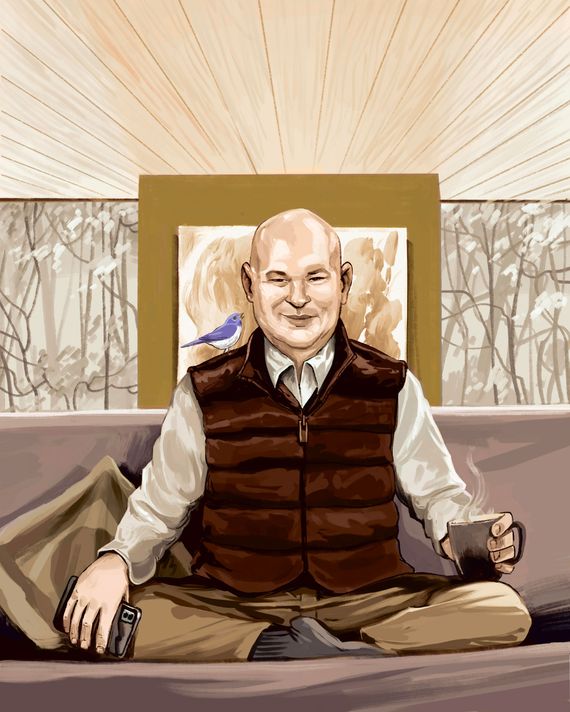

He told me about all of this six months after the Arizona horseback ride as we hiked together in a valley of the Wasatch Mountains in Utah, near one of the homes where he spends his time when he’s not visiting Los Angeles or New York for meetings or TV appearances or the like. Schmidt, wearing blue reflective sunglasses, took long, quick strides, rarely slowing or stopping even when the sky darkened and rain fell or when the sun beat down on his distinct shaved head, which was bright pink by the end of ten miles.

If I was having any trouble making sense of what he was doing or why he was doing it, he said, all I needed was to think of a rattlesnake. He had feared them. Full-on “phobia,” he said. Until he moved to Lake Tahoe and met one that changed his life. “He comes out, and he goes out on this rock, and you’d go up and kind of look at him. If you got too close, he’d rattle a little,” he told me. Schmidt just stared at him until, eventually, he understood. “He liked being in the sun. He’s not going to bother anyone. The only way I think he’s going to bite you is you just step on it or you try to pick it up. And I just watched him. And I was like, That’s how I feel. Just want to lie on my rock. I want to be left alone. I want to not have a person constantly lying, abusing, piling on, who’s in the family of the candidate, who uses their name like a weapon.”

By the time he had checked into the Ritz this winter, upon the horse and among the cacti, he knew all of this about himself. But only then was he was struck with total clarity about what to do next. “I realized,” he said, “the only way through is to fight.”

Schmidt and I went hiking on Tuesday, May 17, and by then, he had been fighting for 11 consecutive days. Which were five more than he had planned for in the weeks that followed his equine epiphany, when he devised the plot for a publicity blitz and a string of legal threats that would go off, pyrotechnics style, from a Saturday to a Thursday (the best days to generate sustained attention, in his professional opinion). He would harness his experience from his second act — post–McCain campaign — as a corporate-crisis communications specialist to create a crisis for those he felt deserved one most. He called it his “Six-Day War” (he had recently converted to Judaism, he said).

He thought about “the tactics and how you’re going to make a point, build momentum towards your point in an interconnected series against bigger organizations, bigger names,” he said.

He had two main objectives: to correct the record of the 2008 election and the narrative of the collapse of the Lincoln Project to minimize and redact his role, respectively. And two main targets: news organizations and individuals who had been reporting or writing or speaking about him in ways he disliked and thought unfair. He wanted to to goad his media critics into defending their stories and to wait for another insult from Meghan McCain to launch an attack against her. “If the convention is you’re supposed to take the abuse and that you don’t push back against big news organizations and a bully who pushes you,” he said, “you know, I’m good with it.”

One of the opening volleys of his war was an essay he published on Substack. It was a targeted attack on the McCain family. In it, Schmidt said that John McCain had lied when he denied having an affair with a lobbyist during his presidential campaign and that a top McCain staffer had maintained unethical financial ties to Russia. (The staffer in question declined to comment.) Schmidt also said McCain’s picking Sarah Palin as a running mate was not his fault, as has long been the conventional wisdom; in fact, he had only suggested that the campaign consider her as an option.

Meghan McCain offered up, in Schmidt’s view, a casus belli when she liked a tweet that referred to his time at the Lincoln Project as “running a pedo racket.” He unleashed on Twitter, mocking her book sales and calling her “a bully, entitled, unaccomplished, spoiled and mean.” He said she embraced cheap celebrity and disrespected the history of her family. He shared a personal anecdote suggesting her mother was not proud of her. A day later, he directed another Twitter thread at her, concluding with “These are the last words I will ever say to you. Our relationship wasn’t working for me. It was toxic. You know, with all the abuse, smearing and lying. I tried to get you to listen but you are a screamer and not a listener. We have to break up and say bye now.” (Schmidt admits that he has had zero contact with her since the 2008 election and that he has never reached out to resolve their issues privately, aside from a legal letter addressed to her from the Lincoln Project and a letter that Schmidt wrote to Cindy McCain asking her to make her daughter stop speaking about him in public.) He also attacked Palin, who is now running for Congress in Alaska, calling the former vice-presidential candidate unfit for any position of authority, “even as a crossing guard,” and accusing her of not knowing that America had fought the Germans in the Second World War.

I asked if, considerations of history and truth aside, he thought it was decent to tell off a family whose grief has been interrupted by outsiders who will not allow their husband and father to die. “I have no sympathy for her whatsoever,” he said of Meghan. “I just, I don’t. It was necessary.”

Separately, he went off on the New York Times, the Associated Press, and New York Magazine for stories about the Lincoln Project leadership’s actions (or nonactions) in response to what Weaver was alleged to have done. He was preparing legal letters, he said, to demand corrections to stories that he felt unfairly mentioned him, which he said journalists only did because he was famous and his name would generate reader interest. He disputed that leadership at the Lincoln Project was aware of Weaver’s alleged misconduct, and he said the alleged misconduct had taken place “before the Lincoln Project.” Schmidt thought it was absolutely profane for the press to utter his name in the same breath as Weaver’s, and he insisted that Weaver’s alleged sins were simply not a story about the Lincoln Project.

I asked if he was familiar with the proverb “He that lieth down with dogs shall rise up with fleas.” He turned his head toward me and made a serious face. “A hundred percent, a hundred percent. No disagreement whatsoever,” he said.

Yet the list of grievances was growing. Schmidt was willing to sue almost anybody he needed to sue, he said, and he had already spent $2 million on lawyers. If he blew through his entire fortune in this process, he added, it would be more than fine with him. It would be worth it. He posted again on Substack, this time to battle the Times over its characterization of his first Substack post. In conversation with me, he threatened an additional lawsuit against the paper over the issue.

“This is almost like a gaslighting,” he said. “I’m not crazy. Look at what I wrote.” (What he wrote: “Ultimately, John McCain’s lie became mine.”) “Look at what the story said.” (What the story said: “Former Top McCain Aide Says He Lied to Discredit a Times Article.”) He handed me his phone and asked me to read a long text message he had sent to the Times reporter Jeremy Peters. I noted that Peters had not replied. “Three hours ago,” Schmidt said. “And I will sue them.”

My eyes must have widened. Sue the Times over Jeremy’s piece? I asked. Schmidt shrugged. “I will absolutely sue them over Jeremy’s piece,” he said. “You don’t think I can pierce in a discovery, unveil the malice standard of the New York Times on something that is erroneously wrong?” (I should pause here to note that I am friendly with Schmidt and with Meghan McCain, who declined to comment for this story, and I am friends with or connected to nearly every reporter and media institution Schmidt is complaining about or threatening to sue, including, obviously, New York Magazine. )

By its nature, a war has at minimum two sides. To date, Schmidt’s Six-Day War has looked more like shadowboxing. No one he has attacked has even attempted to respond. Which he believes is not because people are fearful of engaging with a person they believe may be at worst totally unstable and potentially extremely litigious but because they know the truth is just as he sees it. Silence is an admission of guilt, he said, and he believes more than ever that forgiveness is for suckers. He looked me in the eye and told me not a single friend or acquaintance had called him to express concern about his behavior or to ask if he is okay.

As people across the disparate factions of the ideological political and media elite wondered if he had lost his mind, Schmidt said he had only grown more certain of the righteousness of his actions. If it seemed to anyone that he was knifing a dead man because it was the only way he knew how to hurt the dead man’s daughter, and if a widow seemed to be the collateral damage in that act of warfare, well, the only defense he needed was that all of this was a part of history. The public interest outweighs the private heartache. He knew that among his fans online, where in the previous administration he became a hero of the Never Trump and #Resistance movements, no one would judge him for that stance. He hadn’t lost his mind, he said. He had found freedom and peace within it. Not that free means “finished.” “Another shoe is about to drop,” he said. (He would not disclose details about the shoe on the record.)

Schmidt wears western shirts with pearlescent buttons, blue jeans, and boots made of reptile skin. He has a weird thing about eye contact, as if he believes on some level that every human interaction is a staring contest that he must win. He has a habit of speaking in winding monologues, covering in a single run-on sentence, perhaps, the entire history of Rome and the golden age of television and the night Elvis died and the majesty of Lake Tahoe and the sins of Donald Trump and the dietary wisdom espoused by Eric Adams, and he is prone to making odd pronouncements about himself at unexpected moments. At different times, he declared to me, out of nowhere, “I would’ve been a great FBI profiler” and “I had one of the first Labradoodles ever.” I asked him to expand on the second thing, and he delivered an impassioned speech about how people will often refer to their Labradoodle only to reveal that the mother of their alleged Labradoodle was also a Labradoodle, which Schmidt said means the dog is not a Labradoodle at all: “This is an important thing about Labradoodles. A Labradoodle is half-poodle and half-Lab. Two Labradoodles mating do not produce a Labradoodle. That’s a mutt.”

After the hike, we returned to his house, which is generously decorated with modern art, political artifacts, and pieces of Americana. A woolly-mammoth tusk, a seven-foot totem pole, a portrait of a farmer who looks like the Marlboro Man that was painted by a British guy, a neon cowboy. Framed copies of Life magazine. And flags. So, so many American flags. His younger sister, Jen Schmidt, said he has always maintained a collection, and when they would fight as kids, “I would run into his room and grab one, and I would threaten to let it touch the ground and he would just fall to his knees and stop.” The flags in the house now are largely behind glass.

Jen is a clinical mental-health counselor who specializes in trauma, and it is her professional and personal opinion that her brother, whom she calls Steven, is completely sane. Online and on television, he may seem “angry or intense or bombastic,” she said, but in truth he is more “thoughtful and deliberate” than ever. “I always say you’re only as sick as your secrets,” she said. “I’m so relieved that his truth is out.”

In the living room is a wooden chair inscribed in bronze and signed by Mitt Romney. “There’s always room for you at our table,” it reads. Romney had sent the gift while courting Schmidt to work on his 2008 presidential campaign, an offer he turned down. (“There are literally enough of these chairs to fill an auditorium,” a Romney source said. “There was nothing special about his receiving a chair.”)

The prior evening, as we’d been hanging out there, Schmidt had shown me an even stranger piece of campaign memorabilia. After a disastrous debate-prep session with Palin in 2008, he ordered a member of the staff to destroy a recording of it: “I told him, ‘Do not let this tape out of your sight. Take this tape. You pull this tape out, you cut this tape to pieces. You take this tape, cut it to pieces, and you put it in a bowl of water, and you microwave that tape. And then you take that bowl of water and you fucking light it on fire. And you take all that tape, you put it in a bag, and you FedEx that tape to my house.” Schmidt walked into the kitchen and emerged with a paper Whole Foods bag. He stuck his arm inside and lifted out a handful of the cut-to-pieces, drowned, and microwaved-and-lit-on-fucking-fire remains. He threw his hand up and the tape fell like confetti onto the floor. He was thinking of turning the mess into objets d’art. Maybe paperweights.

Sitting beside the fire on the patio, he said he had never been so happy. “I’ve come to a view that life is not so much about a destination, but it’s about a journey,” he said. “And I planned this for months, okay? I think I was ready. You had to get ready. I was like, I’m physically ready. I’m mentally ready. I’m spiritually ready. The lawyers are ready. All I got to do is wait until the timing is right.”

That peace had been impossible before because he could not accept that people had said things about him that he believed to be untrue or unfair. He could not tolerate that he heard about a meeting where a big-time CEO had floated his name and, in a room full of people who mattered enough to sit there with the CEO, someone said, “It says a lot about someone who wasn’t invited to John McCain’s funeral.” He could not get over that humiliation. He was sure he did not deserve this because he was sure he was a good person.

If Schmidt is a hero (and millions of people view him as one), it is because he has told the truth — as he did about Trump from inside the ranks of the Republican Establishment. He did that even though he was aware that he would face attacks on his character. And he did so even though people would ask why he had waited so long and would question his motivations. Telling the truth, whenever you tell it and however you tell it, is better than having not told it at all.

For those who look at Schmidt and see more of a canny political hack than a truth-telling hero, well, it’s not quite so simple. In an editorial titled “Leaker, Liar, Turncoat, Nutjob,” the pithy neocons at the Free Beacon asked, “Was Schmidt lying then, or is he lying now?” And though the defense might have ruled out insanity, critics were already wondering how his war against Meghan McCain and the press was serving Schmidt’s interests. Money is always an easy answer, though Schmidt has claimed that isn’t his objective. His Substack bombshell, after all, was called “No Books. No Money. Just the Truth.” Some theories conclude he must be wagging the dog or getting out ahead of something, though nobody has fixed ideas about what exactly he could be trying to hide or distract from or define on his own terms. A lawsuit? An investigation? A damaging story? A reinvention? No, Schmidt said, and no, no, and no.

And then there’s Palin. She is running for the at-large congressional seat in Alaska left vacant after the death of Don Young. If she advances in the June primary and wins the August special election, she will return to the national political stage and to mainstream political and cultural discourse, bringing along with her the ghosts of the 2008 campaign and all that followed. Schmidt doesn’t dispute, even now, that when he saw Palin in 2008, he identified her as a “star.” He knows, better than most, the kind of power that can have. But his PR offensive was not motivated by Palin’s reemergence, he insisted. “One hundred percent, that didn’t factor into the decision,” he said. “But her return in seeking a high federal office is something that — I want to be unencumbered to be able to talk about who this person is.”

Without Palin as an explanation, I had to know: Why now? Why wait all this time? Why wait until it’s not just too late to have a direct political impact but also too late for this to have required as much courage as it would have during almost any other point of the past 14-plus years. Until August 25, 2018, John McCain was alive.

“The 14 years,” Schmidt said. He paused. It was very important for me to understand this, he said. If I took one thing away from our conversations, it should be this. “It was time when it was time. I feel, like, very certain about that.”

More power trips

- I Examined Donald Trump’s Ear — and His Soul — at Mar-a-Lago

- The Conspiracy of Silence to Protect Joe Biden

- Jerry Nadler Says Michael Cohen Is a Con Man Again