This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

During one of our phone calls in mid-November, Chase Strangio mentions that it’s officially Transgender Awareness Week. He isn’t particularly feeling it. “I’m like, Oh my God, please less awareness, less visibility,” he says. “I think we all need to take a break from thinking and talking about trans people.”

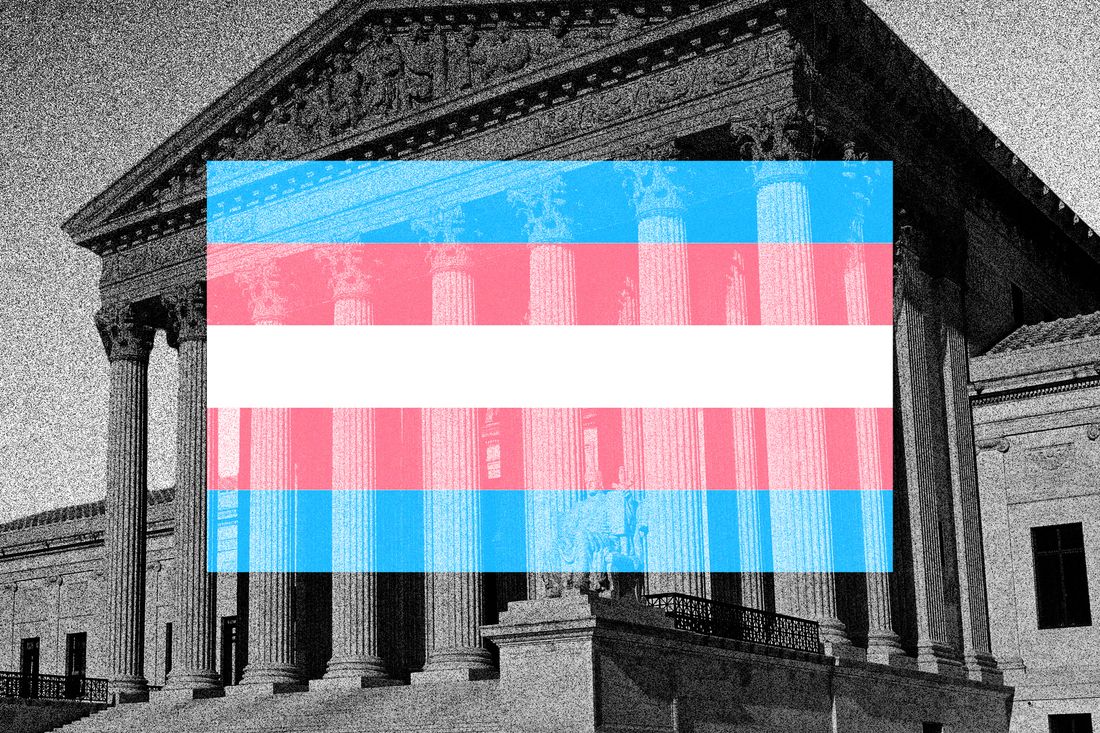

It’s lightly off message coming from the co-director with the ACLU’s LGBT & HIV Project, who, on December 4, will become the first openly transgender attorney to argue a case before the Supreme Court. United States v. Skrmetti is a challenge to Tennessee’s ban on gender-affirming care for transgender minors, contending the law is unconstitutional.

And yet what else could there be but weariness — if not anguish — weeks after Donald Trump won the presidential election with a campaign that spent tens of millions of dollars on ads declaring, “Kamala is for they/them. President Trump is for you,” while Harris was conspicuously silent on the issue? And at a moment when centrist pundits are blaming the Democrat’s loss on her being overly deferential to both trans-rights claims and nonprofit advocacy groups, including the ACLU, and when many lawmakers are already preemptively bargaining with conservative forces about which so-called “social issues” to cede, with trans rights atop the chopping block? Republican-led states have already unleashed a torrent of laws targeting trans people across the country, with 16 states adding 47 new laws this year alone — focused on restricting health care, participation in sports, library books, and beyond — with many more in the pipeline.

The choice to take the bans on transgender care for minors all the way to the Supreme Court despite public anxiety and conservative momentum was made by the ACLU and its partners. (They were joined by the Biden administration, whose petition the Court accepted.) It’s hard, I say to Strangio, to imagine doing anything more visible, at least in the world of law.

To go not only to the Supreme Court but to this Supreme Court — the one stacked with three Trump appointees, plus Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and John Roberts, all of whom voted to overturn Roe v. Wade — to ask for the constitutional recognition of trans people’s humanity at a time of bipartisan backlash and a month before the MAGA party takes over the legislative and executive branches? As Kate Redburn, an academic fellow at Columbia Law School and co-director of its Center for Gender & Sexuality Law, tells me, “It’s understandable to some extent why the case was brought up.” In their view, the bans on trans health care for minors are blatantly unconstitutional. “But now the question is, What will the Court do?” they ask. “I can’t tell the future, but I think the signs are bad.”

Depending on how the Court justifies itself and how far it goes, a loss for the plaintiffs — young trans patients, their parents, and a doctor — could have sweeping consequences. The lower-court opinion that’s being appealed, Strangio points out, is written in a way that makes it easier for states, or even the federal government, to ban gender-affirming care for adults as well. Further, the specific question the Court has agreed to hear is whether these bans authorize unconstitutional sex discrimination, which means its ruling could very well chip away at existing protections based on gender and sexuality. The Court could even quietly dilute decades of precedent that have barred many other forms of discrimination, including on the basis of race. Or it could choose to reinforce them.

It’s a high-stakes bet heightened by the fact that, when Trump takes over, the government is expected to literally switch sides in the case, joining Tennessee to argue for the constitutionality of its ban. Some allies of the trans-rights cause have expressed worry to me privately about bringing the case this far, fearing unintended consequences, but none wanted to discuss their concerns publicly when the movement is up against so much. When the right has captured the courts, the presidency, Congress, and many statehouses, the options can look like either doing nothing or going down fighting.

Strangio, for his part, argues there was little choice but to bring this case. “The consequences of these 24 state laws banning medical care for trans young people are so drastic and so severe,” he says, and the lower federal-court decisions upholding these laws so far “open the door to so much more.” From his perspective, “the question is, How do we minimize that harm?” Like it or not, Strangio says, the issue was headed up the legal chain, and if they hadn’t brought it, opponents could have selected and brought a case with a set of facts more in their favor.

“Am I scared? Of course. It’s terrifying,” he says. “Do I think we had a choice? No.”

The young plaintiffs in the Tennessee case are named as L.W., Ryan Roe, and John Doe. “For years,” the ACLU brief on their behalf says, in terms that seem carefully chosen to emphasize deference to parents and medical experts, these young people “experienced debilitating distress because of gender dysphoria. It was only after careful deliberation with their parents and doctors that they were prescribed puberty-delaying medication and hormone therapy that finally alleviated their suffering.”

Until very recently, there were no laws barring such treatments for minors. The first categorical ban was introduced in 2020 in South Dakota. Strangio admits to having been taken aback by this “relatively aggressive and quick pivot”; anti-trans legislators had previously focused their energy on laws banning trans people from using the bathrooms that match their gender identity. Then Arkansas passed a health-care ban for minors in 2021. Even then, the state’s governor, Asa Hutchinson, himself no liberal, vetoed the bill on the grounds that it was “legislative interference with physicians and parents as they deal with some of the most complex and sensitive matters involving young people.” (After the statehouse overrode his veto, the ACLU successfully blocked the law in court on a temporary basis.) A barrage of identical laws followed, soon blanketing half the country with restrictions that subject doctors to ruinous fines and the potential loss of their licenses for treating minors with hormones or surgery. “And so,” Strangio says, “we go from zero in 2020 to half the country by the end of 2023.”

The official question up for consideration by the Court is whether discrimination against trans people qualifies as sex discrimination, thereby entitling them to protection. If it does, the laws will likely fall.

American anti-discrimination law has been built by scaffolding new claims onto accepted ones. For generations, the Supreme Court did not recognize that treating men and women differently was unlawful under the Constitution, allowing states to keep women out of jobs and civil responsibilities — from bartending to jury duty. The queer attorney Pauli Murray found a way through in the 1960s, proposing that the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, which had been adopted during Reconstruction, could be a tool to strike down sexist laws and policies. In a series of cases in the 1970s, then–ACLU attorney Ruth Bader Ginsburg persuaded a much more moderate Supreme Court to agree. Then, as a justice in 1996, Ginsburg wrote the majority opinion in United States v. Virginia ( 7-1, with Scalia dissenting and Thomas recusing), ruling that government classifications on the basis of sex deserved heightened “scrutiny.” It wasn’t that the government could never treat men and women differently, as they categorically could no longer do on the basis of race, but that courts needed to look closely at whether the laws relied on “overbroad generalizations about the different talents, capacities, or preferences” of men and women.

Tennessee and the other states that have passed bans on trans health care for minors argue that because both trans boys and trans girls are denied the treatment in question, there is no sex discrimination: Everyone is cut off, no one sex is favored. Both the Biden administration and trans advocates counter by drawing on their one big win at the Court — one authored by, of all people, Trump appointee Neil Gorsuch, in what turned out to be the halcyon days of 2020. In Bostock v. Clayton County, Gorsuch and Chief Justice John Roberts joined four justices appointed by Democrats in arguing that the 1964 Civil Rights Act’s prohibition on employment discrimination “because of sex” had to protect people targeted on the basis of gender identity and sexuality, too. They rejected the argument that a fired trans funeral-home director wasn’t experiencing sex discrimination because the bosses would have fired both a trans man and a trans woman. “It is impossible to discriminate against a person for being homosexual or transgender without discriminating against that individual based on sex,” wrote Gorsuch.

There are previous examples of the Court recognizing unconstitutional discrimination even as it is told that everyone is being treated the same. Loving v. Virginia, which struck down bans on interracial marriage, found that even though all races were prohibited from marrying outside their race, the prohibition was still unconstitutional.

The ACLU argues that the Tennessee ban “enforces a government preference that people conform to expectations about their sex assigned at birth.” (That preference is self-evident but is also made close to explicit in the law’s language describing its purpose as “encouraging minors to appreciate their sex.”) Meanwhile, there are exceptions in the law for the same treatments for different purposes — surgery on intersex infants or medication for early puberty and polycystic ovary syndrome. One of their clients, Strangio says, would in theory be able to access puberty blockers and hormones to “conform his body to a typical male puberty. It’s prohibited because he has the birth sex of female. If he had a birth sex of male, he could do those things under Bostock, under this court’s equal-protection cases,” he says. “The statute turns entirely on whether medical treatment is gender conforming and nothing else.”

A few lower courts agreed with this reasoning, extending the logic of Gorsuch’s Bostock decision, but the victory was short lived. By the beginning of the fall, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals robustly upheld the law, rejecting the sex-discrimination argument entirely. (In a dissent, Judge Helene White, a George W. Bush appointee, wrote that such laws’ “texts effectively reveal that their purpose is to force boys and girls to look and live like boys and girls.”) Earlier this month, the Seventh Circuit followed suit by ruling Indiana’s ban on trans health care for minors wasn’t sex discrimination: “The law does not create a class of one sex and a class of another and deny treatment to just one of those classes.”

These are fierce headwinds. The Supreme Court has been known to read the national mood to intuit how far it can go, and the political backlash against trans rights is far fiercer than it was in 2020 with Bostock. Following Trump’s appointment of Amy Coney Barrett to fill Ginsburg’s seat, there are now only three liberals, meaning at least two Republican appointees — perhaps Gorsuch and Roberts again — would have to agree to extend Bostock’s logic in order to rule the Tennessee ban unconstitutional.

A loss could be catastrophic to trans rights. But the Sixth Circuit opinion seemed to potentially threaten more, spooking scholars of sex-discrimination law by using some language from the Dobbs decision (striking down Roe v. Wade), which claimed, almost as an aside, that abortion bans did not discriminate on the basis of sex. The inclusion of this language seemed to open the possibility that governments could discriminate on the basis of sex if they justified it on health grounds.

If cases like Skrmetti provide a vehicle for conservatives to expand how much the government can discriminate on the basis of sex, says Redburn, “that’s a continuation of a decadeslong project to undermine anti-discrimination law.” That the right-wing has had some success in this regard in federal courts, wrote Katie Eyer, the legal scholar who helped craft the winning arguments in Bostock, suggests “the potential of a very dark future”: “More widely adopted, such arguments could profoundly limit the reach of anti-discrimination law — for all protected classes, from race to disability to age to sex.”

Not challenging these laws offers its own bleak outcome: allowing the bans patchworking the states (and lower-court opinions ruling against care for trans minors) to stand. “Our hope is that the Court will do what its actual function is in our legal system, which is to engage in error correction where necessary,” says Chinyere Ezie, senior staff attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights. “We’re very wary of returning to a model where the state you live in determines the extent to which you enjoy full personhood.” Without legal protections, she adds, trans people are further thrust into the poverty, lack of housing and employment, and criminalization that are disproportionately their reality.

For a brief moment on December 4, trans people will have the full force of the U.S. government behind them at the Supreme Court. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar, considered one of the most dazzling oral advocates of her generation, will stand before the justices to argue for their rights.

Next will be Strangio. Imara Jones, an advocate and journalist who founded TransLash Media, an independent news organization specializing in telling trans-focused stories, remarks to me that the paradox is typical of this moment. “The fact that Chase is there arguing this case is historic,” she says. “Full stop, period. It’s historic. And it represents so much incredible change. At the same time, the reason he has to be there is deeply disturbing. You have these things happening at the same time — trans people breaking barriers and virulent backlash.”

Strangio himself doesn’t want to say too much about the significance of his own participation. “I am not thinking about that part of it because at the end of the day, the stakes are the same regardless of if I’m trans or not,” he says. “And this fight has been a fight that almost every lawyer in every big LGBT org has been working on for the last four years. It’s a collective effort on behalf of our community.”

In the Supreme Court cases that struck down sodomy laws and same-sex-marriage bans, much was made of the presence of actual gay and lesbian people in the courtroom, whether in the form of lawyers arguing cases or clerks who were close to the justices. Perhaps, I say, it will be harder for some of the more hostile justices to be openly bigoted to his face. Strangio points out that gay people being in the room didn’t stop casual prejudice from surfacing in the past. But then he offers one way that his identity could matter.

“If nothing else, I’ve lived this health care. It has enabled me to stand before them at that lectern,” he says. “So that is a truth that is undeniable, that will be present in the courtroom, that certainly the other trans people who will be present in the courtroom will understand.”

He’s preparing for the case in all the traditional ways — practicing with his colleagues in moot courts, rereading opinions, and playing back those oral arguments. But he is also getting ready in ways the justices won’t be able to see. Recently, he got a quote from a 1969 Murray poem, “Prophecy,” tattooed on his back: “I have been cast aside, but I sparkle in the darkness. / I have been slain, but live on in the rivers of history. / I seek no conquest, no wealth, no power, no revenge; I seek only discovery / Of the illimitable heights and depths of my own being.”

Queer friends have been dropping off meals for him as the trial approaches. “I see all around me, trans people taking care of each other, helping people get their documents changed, getting people the tools they need, helping people figure out plans if they have to leave the country,” Strangio says. “And all of those things are so bleak and so hard, and yet people are managing them collectively.” Win or lose, he says, that work will continue.

And if they lose? In our conversation, Redburn cited a 2011 article written by Yale Law’s Douglas NeJaime, called “Winning Through Losing,” on the political gains that can counterintuitively come when a movement faces defeat in court. The clarity of a loss can generate new energy and strategies.

“A court decision that guarantees rights is, of course, what you’re always after,” says Redburn. “But you may be under conditions where that might not be possible. Losing the case is not the same as the movement losing.” The question — one of many, really — is how much may be lost in the meantime.