This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

It’s bad news when your university creates a committee to ensure that you don’t publish any research papers without its approval. It’s worse news if the only other person facing similar scrutiny is a man investigating alien abductions. This was the situation facing the trauma researcher Bessel van der Kolk in the mid-’90s when Harvard Medical School informed him that all of his future publications would be vetted for quality control. The other professor Harvard had slapped with a similar degree of oversight was psychiatrist John Mack, who had spent years studying people who claimed to have been taken by aliens and, by the mid-’90s, ended up believing them.

At the time, van der Kolk was in his early 50s and an academic star who looked the part: tall and winsomely thatched behind rimless glasses. “There was a sense that Mack and I were doing research that was equally wacky,” van der Kolk recalled. They did have one thing in common. Both studied people who claimed to have had experiences the scientists couldn’t definitively verify. But while Mack’s subjects gave detailed accounts of their alien encounters, van der Kolk’s patients had memories of horror that were more like fragments than coherent narratives, details that could lurch suddenly out of a dimly remembered past. The car-radio jingle that was playing before the explosion, the smell of the dollar-store deodorant he was wearing — these shards could hurl patients back into a state of panic. Traumatic memory, van der Kolk argued, is not so much a narrative about the past; it is a literal state of the body, one that can bypass conscious recall only to resurface years later.

This was the core of van der Kolk’s thesis: Traumatic memories are not ordinary memories. But then, trauma science is not ordinary science. By 1995, debates within traumatology had ignited a culture war that was beginning to devolve into a circus. Pruned of nuance by daytime shows like Oprah and Phil Donahue, van der Kolkian theories of traumatic dissociation had transmogrified into the “recovered memory” movement, in which masses of people, from well-meaning therapists to opportunistic grifters, coalesced around the idea that distinct memories of abuse could surface wholesale many years later.

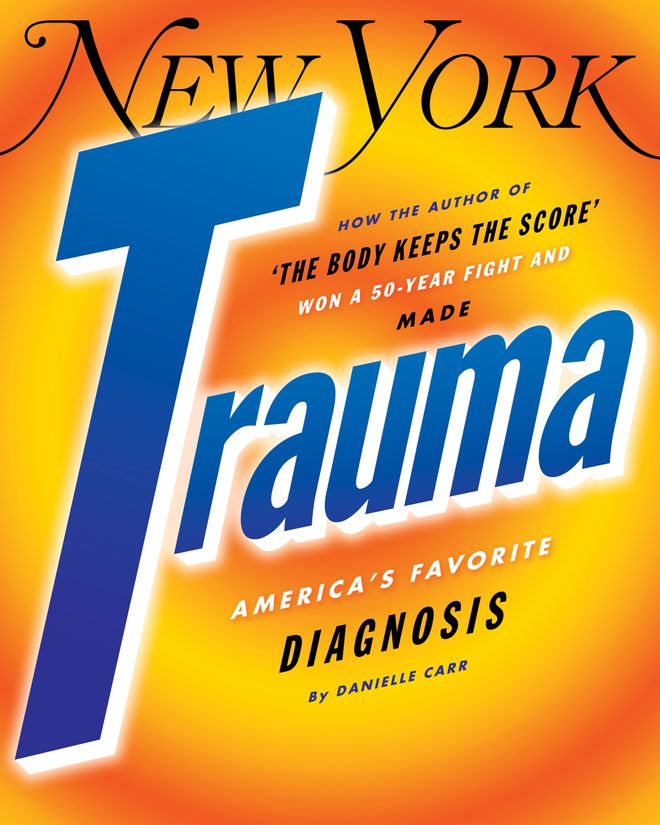

Cover Story

As the idea of recovered memories went mainstream, growing ranks of middle-class women came to identify as traumatized, often by claiming to have resurfaced recollections of childhood sexual abuse. Patients with multiple personality disorder — with their shrink/co-author/agents in tow — sprang up to furnish harrowing accounts of the torture they had endured as children. People went to jail. It was fantastic television. Skeptics thundered that it was all gender radicalism and bullshit science, a culture of victimization — political correctness gone mad. As one of the researchers whose ideas formed a linchpin of the recovered-memory camp, van der Kolk was vulnerable to the backlash. After the psychiatry department closed down the trauma clinic he had spent 12 years building and put the quality-control order on his publications, van der Kolk stormed out of Harvard, shoulders chipped and with a determination to bend psychiatric orthodoxy back in his direction.

Nearly three decades after leaving Harvard, van der Kolk is currently the world’s most famous living psychiatrist and the author of The Body Keeps the Score, which has spent 248 weeks on the New York Times paperback-nonfiction best-seller list and counting. To date, it’s sold 3 million copies and been translated into 37 languages. Published by Penguin in 2014, The Body Keeps the Score is van der Kolk’s manifesto. It argues that trauma constitutes a special type of memory, one distinct from the systems used to remember grocery lists or the name of your childhood pet. Ordinary memories are representations of the past that can change and fade over the course of ordinary life, his argument goes, while trauma is a literal incursion of the past into the present, which can produce physiological effects whether or not the traumatized person consciously remembers the event. What this means is that the body can register what happened in a way the person might catch up to only years later. Even after the traumatic event is over, the van der Kolkian model goes, the body stays on alert, reliving the threat of a now-nonexistent danger.

The Body Keeps the Score isn’t the kind of title you would expect to achieve cult status; it’s a technically dense overview of a theory of traumatic stress that once spurred 20 years of scientific controversy. After a respectable performance following its publication, The Body Keeps the Score began a steady climb in the publishers’ charts, and its prominence — dating to roughly 2018 — could not be attributed only to the COVID-generated surge in self-help titles. Somewhere along the way during the Trump years, among the heady thrashings of Me Too and the soul-searching doldrums of the lockdowns and the average listener of The Daily discovering white supremacy, trauma became the inflationary currency through which we transact our lives. Look one way, and Prince Harry is livestreaming an interview about the trauma he incurred as a member of a hereditary monarchy; look the other, and books like Arline Geronimus’s Weathering are arguing that the violence experienced by America’s impoverished racialized underclass should be understood as trauma passed down epigenetically across generations. Within the gulf separating a British prince and, say, a poor Black teenager on Chicago’s South Side lies the vast range of human experience that increasingly seems to fall within the ambit of trauma.

In his ascent, van der Kolk has done for trauma what Carl Sagan did for the galaxy. Today, the prevalent trauma concept is fundamentally van der Kolkian: trauma as a state of the body, rather than a way of interpreting the past. This means that getting the patient unstuck from the past requires working with the body and teaching it to unbrace itself from a chronic “fight or flight” mode.

Last summer, I met van der Kolk at an ashram in the Berkshires to attend his weeklong trauma workshop. The program, which he has given hundreds of times in various forms in dozens of countries, combines lectures drawn from The Body Keeps the Score with healing exercises led by Licia Sky, a bodyworker and van der Kolk’s wife of ten years. Our first evening began with what the two of them — swiftly correcting someone who used the word icebreakers — dubbed “the work”: such exercises as mirroring breath and gait with strangers, making eye contact that bordered on the harrowing, accepting an invitation to dance, or, in my case, “noticing and sensing what this invitation to dance brings up, maybe a feeling of refusal.” The end of the night found attendees sprawled across the “thrilled-exhausted” spectrum, depending on how their bodies had kept the score for the past hour and a half.

Today, van der Kolk’s renown — built on translating neuroscience into language accessible to people searching for a cure for their pain — has placed him in a position straddling scientific celebrity and guru. On the first night, every attendee who took the mic — the therapists, school counselors, and medical professionals, some of whom had the tuition comped by their employers — admitted they had come for their own healing as well. Later, when I asked two special-education teachers how they had learned about van der Kolk, they laughed: “If you’re in a certain line of work, it doesn’t really make sense to ask us how we’ve heard of Bessel van der Kolk.” For people in “trauma-informed care,” they explained, referring to the professions stretching from schools to hospitals to social-work programs to parole offices to private psychotherapy practices, “he’s like a god.”

But well into this echelon of success, van der Kolk remains palpably embattled. That first night, one attendee joked that, like everyone else there, he had come to learn from “his high holiness here, the holy man of trauma.” He gestured at van der Kolk, who was seated on the ashram’s dais. “Don’t call me that,” van der Kolk snapped back, suddenly on edge. “I’m not a holy man.” In response to questions indicating less than total buy-in, he may give the sense that he’s not exactly talking to you; it’s more like he’s letting you listen in while he corrects the errors of some invisible antagonist. “Nobody’s getting healed here this week,” he muttered when surveying the first-day registration fracas in the lobby earlier. “People come thinking I’m going to fix them, but trauma doesn’t work like that.” Just because a war is over, the van der Kolkian theory goes, doesn’t mean its veterans won’t be left battling flashbacks. Bessel van der Kolk is a veteran of a strange type of war.

Van der Kolk didn’t set out to study trauma. When he landed as an undergraduate at the University of Hawaii in 1962, he told me, he was mainly interested in “surfing, meeting girls, and learning how to dance the hula.” Born in July 1943 in the Nazi-occupied Hague, he arrived to devastation. He was the middle child of five, and sickly. His father, who worked for Shell Oil, had been caught in one of the Nazis’ mass roundups of able-bodied men and sent to a work zone. His mother played piano, and each child learned an instrument (Bessel played piano and cello). “Our mother wasn’t prepared for the demands of a large family,” his younger brother, Jan, told me. When I ask van der Kolk about his childhood, he doesn’t mention any of this. Instead, he tells me about receiving an excellent education in the Netherlands, where he learned to speak six languages and to love classical music.

He came to the U.S. to stay with his uncle, a professor at the University of Hawaii who then left the following year. To pay his bills and tuition, van der Kolk spent several summers as a ward attendant in an asylum, an experience that moved him to devote his life to the field of psychiatry. As an undergraduate, van der Kolk was active in Students for a Democratic Society, and by the late 1960s, it was a mainstream New Left position that mental hospitals were little more than prisons by another name. He was also deeply influenced by thinkers in the anti-psychiatry movement, such as R. D. Laing, and by mentors who emphasized non-medical causes of mental distress. In this model, treating the patient meant treating their social situation as well.

When van der Kolk was beginning his research career, working with patients at the Boston VA outpatient clinic, a struggle was brewing about whether trauma research could become a legitimate biomedical field. Since its first appearance in psychoanalytic consulting rooms, trauma had eluded definition as a coherent neurological disease. The controversy centered on whether post-traumatic stress disorder would become a psychiatric diagnosis.

In the lead-up to the publication of the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1980, Vietnam veterans’ advocacy groups united with psychiatrists who opposed the Vietnam War. This group wanted PTSD to make it into the DSM-III so the state would cover treatment for veterans’ psychological injuries — nightmares, sudden rages, a proclivity to substance abuse. This pro-PTSD camp saw trauma as something embedded in social and political problems outside the patient’s body. Opposing them was the faction of psychiatrists controlling the DSM-III committees, who had bet the house on biological reductionism, or the idea that psychiatric diagnoses are ultimately brain disorders. To this faction, the DSM-III was supposed to act as psychiatry’s coming-of-age as a legitimate medical science, inaugurating a unified system of diagnosis that everyone — from neurosurgeons to insurance companies — could agree on. To them, it was humiliating that other branches of medicine had sailed through the 20th century discovering magic-bullet cures while psychiatry hardly had even a basic understanding of the biological basis of mental illness. The PTSD skeptics on the committees wanted nothing to do with any diagnosis that they suspected lacked the same kind of biological reality of diseases like polio or hypertension.

Even Freud’s original formulation of trauma had been troubled by a crucial indeterminacy: Did trauma come from something that occurred outside the individual’s psyche (say, an explosion or a railway accident) or inside it (a neurotic complex triggered by an external event)? Trauma, in other words, seemed to beg the central question: Does trauma happen when stress tips over some acute threshold, or are people traumatized because of some underlying vulnerability that makes trauma out of what, for someone else, might just be stress? Is trauma even a useful concept, scientifically?

Ultimately, the strength of the grassroots campaign for PTSD, coupled with the undeniable symptoms psychiatrists were seeing in veterans, forced the skeptics to cave. PTSD became an official diagnosis in the DSM-III. The central indeterminacy about what trauma actually is, however, continued unresolved.

In the ’80s and ’90s,” van der Kolk told me, repeating a line he’s fond of, “Boston was for trauma studies what Vienna was for music.” He had married Elisabeth “Betta” de Boer, a Dutch au pair who would become a social worker. Their first child, Hana, was born, then Nick. Every day, van der Kolk would bike from their brownstone in the South End to work at Massachusetts General, one of Harvard’s teaching hospitals. By the mid-1980s, a small but powerful coalition of psychiatric researchers was taking shape to steer what PTSD would mean. In Cambridge, Massachusetts, van der Kolk was the ringleader of this network. For more than ten years, the Harvard Trauma Study Group met every month, forming the first stronghold of what its enemies would later call “the traumatologists.”

In 1984, van der Kolk published his first trauma paper; it contained the seed from which all his future work would develop. In it, he argued that the nightmares veterans were having weren’t like normal nightmares: They came earlier in the sleep cycle and “were repetitive dreams that were usually exact replicas of actual combat events.” That is, unlike normal dreams, which fuse memories, wishes, and anxieties, PTSD nightmares are a literal replay of the traumatic event itself. At a biological level, van der Kolk would soon argue, this implied that trauma is physically seared into the nervous system, more like a scar than a story. This was a big claim. If it was true, it meant trauma could act as a kind of objective proof that something had happened. A person can lie, but the body cannot.

Van der Kolk set out to determine what kind of physiological system could account for this type of “body memory.” In an extraordinary paper from 1985, he proposed the first neurobiological model for PTSD, one that could explain why trauma victims so often return to situations in which the traumatic experience will likely repeat. Freud had called this the “repetition compulsion.” When animals are continually subjected to inescapable shocks, it triggers a stress response that includes the release of endogenous opioids as an analgesic. When the stressor ends, van der Kolk hypothesized, it could cause an opioid-withdrawal effect, which the stressed subject might try to fix by seeking reexposure to the stressor. Perhaps, he posited, chronic exposure to stress created trauma junkies addicted to the high of endogenous opioids. Maybe this was why, for instance, abused children often grow up to choose violent partners.

This 1985 paper contained all the signature features of van der Kolkian trauma. Most notably, it synthesized the two factions that had clashed over the PTSD diagnosis. From the biological-reductionist camp, it took the idea that trauma is a literal state of the body, and from the veterans’ activists, it took the premise that trauma is caused by social and political violence and would therefore need more than medication to treat.

By the late ’80s, van der Kolk was collaborating with Harvard psychiatrist Judith Herman, another founding member of the Harvard Trauma Study Group. Herman was one of the first people to research father-daughter incest, and her findings indicated that a vast conspiracy of silence was hiding the extent of domestic abuse nationwide. With Herman, he began to develop a model arguing that borderline personality disorder — a diagnosis overwhelmingly assigned to women with a history of abuse — was, in fact, a form of post-traumatic adaptation, or what Herman would eventually term “complex PTSD.” The borderline patient’s dysregulated emotions were equivalent to a combat veteran’s flashbacks, they argued, while her fragmented or missing memories were similar to the veteran’s disordered experience of time.

As clinicians, the two researchers also began seeing women who, as adults, had come to understand that they were sexually assaulted as children. In most cases, the patients knew the gist of what had happened, though without remembering specifics. There was Carmen, a 21-year-old who had accused her father of assaulting her as a child, who, in treatment, recalled more specific memories that she hid from her family. In some cases, patients in treatment would dredge up memories of previously forgotten episodes. In a 1987 book, van der Kolk wrote about a 30-year-old woman plagued by “crippling insecurity, compulsive behaviors,” and endocrinological abnormalities; by the eighth week of therapy, she was “suddenly recalling in graphic detail a traumatic incident” of being assaulted by her seventh-grade classmates in a vacant lot.

Herman and van der Kolk began trying to understand why a person who had been assaulted earlier in life might not remember it until later. One of their hypotheses was that, as a child, the patient wouldn’t have known assault was the name of the thing happening to them. Another hypothesis was that the survivor’s body had sealed the memory off from conscious awareness and stored it in another part of the nervous system. If the second hypothesis were true, the traumatologists argued, it would suggest the presence of two memory systems: the everyday one and the traumatic body memory. By the late ’80s, van der Kolk’s traumatologist camp had produced some clues that a second memory system might exist, but as for a coherent biological model? They just didn’t have it. In the absence of a robust neurobiological model, the traumatologists cast about for other explanations. One they leaned on was dissociation, or the notion that trauma could fragment someone’s experience so drastically that entire swathes of memory would break off, plaguing the traumatized person until the memory was recovered and integrated.

At the time, scientists did not agree on whether it was possible to recover memories that had been suppressed or lost in traumatic dissociation, but as long as the debate stayed in the academy, things remained civil. The fusillades started when, in the late ’80s, the academics began serving as expert witnesses in recovered-memory lawsuits. As a traumatologist luminary, van der Kolk served as an expert witness for the prosecution in a series of clerical-abuse cases brought against the Catholic Church, testifying that it was scientifically plausible that a victim might not remember or recognize abuse until years later. Opposing the traumatologists were researchers like Elizabeth Loftus and Richard McNally, who argued that, actually, memory does work in a pretty straightforward way.

As the controversy over recovered memories traveled from the courtroom to the paperback market to, eventually, the talk-show circuit, the movement began looking more like the bad-faith gloss given by its critics. Things were starting to get pulpy. Self-help blockbusters such as Ellen Bass and Laura Davis’s 1988 The Courage to Heal listed relatively vague and common “symptoms” (fatigue, anxiety, difficulty remembering early childhood) as evidence that the reader was repressing memories of childhood sexual abuse. Mental-health-care providers, many of them licensed social workers, swung out with eyes peeled for signs of repressed memories of sexual abuse, often using methods like hypnotherapy. Some people became certain they had been sexually abused as children. A 1980 memoir, Michelle Remembers, co-written by a Canadian psychiatrist and his patient (and, subsequently, wife) Michelle Smith, detailed tales of grotesque satanic ritual child abuse. (The book was later thoroughly debunked.)

The traumatologists tried to establish distance between their research and the voyeuristic excesses of its popularization. “Many clinicians,” van der Kolk wrote in 1997, “seem to have suspended their capacity for doubt and skepticism by uncritically accepting as true all stories of sexual or ‘satanic abuse’ in their patients.” But by the early ’90s, the idea of repressed memories had escaped its theoretical origins and was running wild through the culture.

This was the period in which van der Kolk came under academic scrutiny. If you ask him, he says his push out of Harvard was orchestrated by Mass General’s chief of psychiatry, a Jesuit priest who had consulted with the Boston archdiocese on sex-abuse cases. But by the mid-’90s, the recovered-memory movement was on the back foot. In 1994, anthropologist Jean La Fontaine demonstrated that American “specialists” were contributing to the rise in satanic-abuse allegations internationally. That same year, Harvard Medical School undertook an investigation into the work on recovered memories done by van der Kolk’s research assistant; the data was later revealed to have been faked. When traumatology antagonist Richard McNally published Remembering Trauma in 2003, it was a victory lap at the end of the memory wars. Trauma had been reduced to its vulgarization and pronounced junk science.

During the trauma workshop in the Berkshires, van der Kolk often referenced this period in his career, sketching the forces — from the Catholic bureaucracy to the institutional groupthink protecting cognitive behavioral therapy — that he sees as having hounded him out of Harvard. Today, at 80, he lives in a large house overlooking a sweep of field and Berkshires forest. In conversation, he sometimes radiates impatience and is prone to interrupting to give the dialogue the shape he thinks it should take. When I mentioned that I was not convinced by a claim he made in a lecture that a nationwide program of early-childhood-attachment intervention could end mass incarceration, he told me matter-of-factly that I was not qualified to have an opinion. (“He responds best if you push back a bit,” counseled one of his assistants.) He can flip between moody exasperation and winning charm. On the first day of the retreat, he picked me up in his Tesla to purchase wine as a treat for his staff. When we arrived at the store minutes after it closed, van der Kolk glowered at me so darkly I promised to find another one. Later, cautiously, I presented the bottles. “Come on up to our rooms with the rest of the team,” he said, all warmth.

After Harvard closed his trauma clinic in 1994, van der Kolk left for Boston University Medical School and relocated his trauma center in Brookline, Massachusetts. The center’s treatments — ranging from play therapy to internal family systems therapy to meditation — were all rooted in the idea that healing the patient required pulling them out of the dissociative memory system and back into their own body in the present. Within a few years, the center was hosting group therapy sessions for people who had lost someone to suicide, for 8-to-10-year-old abused girls, and for parents who realized their spouse had been molesting their children.

At the time, the Trauma Center’s work wasn’t fringe so much as a niche psychiatric specialty. This changed after 9/11, which transformed trauma into a national public-health crisis. During the Vietnam War, the U.S. government had fought the introduction of the PTSD diagnosis, but the War on Terror found it eager to invoke trauma. “National trauma” was useful; it allowed the U.S. to frame itself as a victim rather than a global aggressor. And as it became clear that, contrary to the government’s promises, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan would not be over soon, veterans’ health care became an urgent political concern. Between 2004 and 2012, Department of Defense funding for PTSD skyrocketed from $30 million to $300 million, placing trauma science on the cutting edge of respectable mainstream psychiatric research.

The War on Terror effected a pivot in the type of trauma research that was funded, toward the neurobiology of PTSD. This came as a vindication to van der Kolk and gave him a chance to shake off the dead weight of the recovered-memory wars. Federal funding was also adopting an increasingly open mind to non-pharmaceutical treatments. Immediately following the 9/11 attacks, van der Kolk and the Trauma Center treated first responders and civilians using eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing, in which a patient thinks about a traumatic experience while a clinician guides the patient’s eyes back and forth. Though initially skeptical, van der Kolk became an EMDR evangelist, leading a study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, comparing EMDR to Prozac for the treatment of PTSD. In 2008, he started the first NIH-funded study on yoga’s effectiveness in treating PTSD. He also conducted research on neurofeedback, a therapy that shows patients real-time readouts of their pulse and brain waves and teaches them to self-regulate. What united this arsenal of “somatic therapies” was that they targeted the body, rather than cognition (like cognitive behavioral therapy) or language (like talk therapy).

Meanwhile, van der Kolk began forging a network of alliances that could transform trauma treatment. (“He has always been an incredible networker,” recalled Herman.) At the time, somatic therapies, ranging from holistic-oriented yoga to “internal sensing” practices, were on the outskirts of accepted treatment. For the group of practitioners long dismissed as New Age flakes, van der Kolk’s enthusiasm came as a godsend. “For the first time, a traditional, mainstream psychiatrist and neurobiology researcher was legitimizing the importance of understanding the effects of psychological disturbance on the body,” Babette Rothschild, the author of The Body Remembers, said to Psychotherapy Networker in 2004. But these new approaches were controversial. In the opinion of Richard Bryant, another trauma researcher, van der Kolk had “marginalized himself as a scientific thinker.”

Van der Kolk’s biggest collaboration was with the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, a group of clinicians, researchers, and families that had been created by Congress to improve treatment for abused children. Starting in 2005, van der Kolk and his allies began a campaign to get a diagnosis they called “developmental trauma disorder” into the fifth edition of the DSM, scheduled to be published in 2013. “Our current diagnostic framework is grossly inadequate to capture the deficits in impulse control, self-regulation, aggression, and concentration in abused and neglected children,” wrote van der Kolk in a 2009 Trauma Center newsletter. Psychiatry, he claimed, needed to understand that a vast array of diagnoses — from bipolar disorder to substance-use disorders to personality disorders — are not so much discrete diseases as, at root, all caused by trauma.

The fight over “developmental trauma disorder” was fieldwide and acrimonious. If accepted into the DSM-5, critics argued, DTD would become a kind of diagnostic blob absorbing an enormous range of diagnoses with little concern for what skeptics believed were crucial differences. Van der Kolk threw his energy into the campaign. When DTD wasn’t included in the DSM-5, it came as a bitter disappointment.

Still, the campaign was a victory in another sense. In the world of therapists, psychiatrists, and researchers, the fight over DTD mainstreamed an expansion of trauma from “acute stressors” (like a bomb explosion or sexual assault) to “developmental traumas,” or all the ways a caregiver’s failure to provide safety can change a child’s development. The connective tissue here, between big-T Trauma (acute) and little-t trauma (chronic, developmental) was attachment theory, a framework developed by John Bowlby, a researcher who had influenced van der Kolk during the Harvard Trauma Study Group years. Scientifically, the expansion was sound, but there were unintended effects. Broadening the scope of trauma to encompass both acute events and developmental stressors opened up a situation in which anyone so inclined could claim trauma.

In the year after the DTD defeat, van der Kolk buckled down to finish a book he hoped would bring his theoretical model to a wider public. “I wanted to write something along the lines of Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning — something a smart 22-year-old could read and think, I want to go to medical school to become a researcher in psychiatry,” he told me. In 1994, he had published a paper in The Harvard Review of Psychiatry titled “The Body Keeps the Score.” It was his first stab at the unified theoretical model the trauma-tologists had long craved. Trauma, the paper argued, is stored as changes in the body’s biological stress response, and the stress hormones released by a traumatic experience can cause chronic hyperarousal while making it less likely that the event will be stored in the “declarative” memory system; instead, the event is stored as fragmentary images or physiological sensations in the “somatic” memory system, which traps the traumatized person into continually reliving it. In the book, van der Kolk laid out these arguments and added his thesis on developmental trauma. The book ends by walking the reader through research on somatic therapies, from yoga to EMDR to theater exercises.

In the years since its publication, The Body Keeps the Score — its cover featuring a painting by Matisse — has become a fixture in therapists’ offices, on Instagram grids, on people’s nightstands. “It connected so many dots for me,” said one of van der Kolk’s colleagues at the Trauma Research Foundation. Online reviewers shared similar revelations. “I get it now,” one reader posted on Reddit. “I am not one broken, defective alien placed in a foreign family on a foreign planet, I am a child who was not seen, heard, or tended to.” Aside from one editor, van der Kolk recalls, “none of us expected this, that it would climb and climb and climb. I still am puzzled.”

Not that it’s so mysterious, why trauma, for so many. Sooner or later, there will come a time when your system of half-measures fails you, when you will want to know what it all adds up to so you can finally get to the bottom of what’s wrong with you. There will be a time when the pain of living will be so great that you will be desperate for a concept. A concept is a tool for hacking edges into the chaos. Then we hold on.

Widening trauma to include both acute and developmental stressors transformed it from a “you have it or you don’t” binary into a spectrum. The result is if everyone’s body is keeping the score, what that score actually adds up to starts to get less clear. Decades of research and millions of dollars later, the heft of neuroscientific findings remains descriptive. Thousands of fMRI imaging studies have shown that traumatized brains tend to activate in certain patterns (for example, with a hyperactive amygdala). But crucial theoretical questions remain. Maybe some people are helped by somatic therapy (as opposed to cognitive behavioral or talk therapy) because of an as yet to be elucidated biological mechanism. But which type of therapy works could also be an effect of how much the patient believes in it, or how healthy the therapeutic relationship is, or how skilled the therapist is. In other words, the van der Kolkian theories may not tell us very much more than what we already knew: that external circumstances and interactions change our bodies, that it’s better to have a community to support you during hard times, that fewer people would be miserable if they were less exposed

to poverty and violence, and that it’s better to try to chill out.

Our 2023 trauma moment has blossomed out of the scientific foundation of van der Kolk’s theories, though what seems to be germinating often appears to be less his specific neurobiological model than what we might call “traumatic literalism.” If you’re the type of person who gets Instagram ads for online therapy, your algorithm has doubtless ushered you toward the archipelago of #attachmenttheory and #complexptsd. There, you can learn how growing up in a dysfunctional family can quite literally deform your nervous system, as often through “invisible traumas” like “parentification” as through outright abuse or neglect. These ideas, leaping off the scientific legitimacy of van der Kolk’s work, posit a ubiquity of trauma that seems to leave hardly anyone in the “non-traumatized” category.

But the appeal of traumatic literalism is not so much its scientific rigor as its scientific sheen, which seems to promise objective, graspable solutions to our defining political crises. For the past three decades, liberals have insisted that the institutions of American power, while flawed, were in essentially good shape. Those for whom the status quo wasn’t working out were welcome to jockey for inclusion by claiming identity-related injury. For a liberal politics of inclusion founded on claims of injury, what could be more useful than a way to turn that injury into biological trauma, something objective, observable, and measurable in the brain? In their focus on narrative — that is, on recovering and integrating declarative memories — the battle lines of the ’80s and ’90s trauma culture wars were staked out along clear lines. If you were a feminist or an antiwar activist, you invoked trauma; if you were a conservative, you didn’t. But today’s literalization of trauma is politically promiscuous. In fact, rather than treating trauma as an ideological weapon of the left, now the right wants in on it too.

Take the 2016 memoir Hillbilly Elegy, by new-right icon J. D. Vance, which invokes the neurobiological impact of the chronic stress he endured in Appalachian poverty to show how rural white voters have been abandoned by liberal elites. Take the lamentations about atrophying manhood and falling sperm counts. Call it what you want, but the core idea is always shaped like trauma. Once, we were whole, but now we’re not; now we suffer from a sickness we struggle to grasp or name. Yet this wound provides our new identity, at once the thing that gives us the right to speak and the only thing we have left to say when we do. Underwritten by its literalism, our trauma is the guarantor of what we believe we are owed.

In this sense, van der Kolk’s ascent has landed him squarely back in the problem that defined his position in the memory wars: If he were to disavow the excesses of how his work is being popularized in order to preserve its scientific bona fides, it would mean taming its viral uptake. Still, during the retreat in the Berkshires, it wasn’t always clear how van der Kolk’s neurobiological model connects to some of the interventions he champions. Take psychodrama, a treatment in his arsenal that literally restages scenes of family trauma. Groups of patients role-play family members, while the patient stands up for themself in the way they wished they could have done at the time. The justification for psychodrama is the idea that restaging the trauma is a somatic treatment, as opposed to talk therapy. But for all of van der Kolk’s genuinely innovative neurobiological work, does it really follow that defending yourself against someone pretending to be your parent is any more “biologically based” than talk therapy? The core mechanism of talk therapy, after all, is learning to notice when you are reacting to the therapist as if they were your parent. This too is a process that changes the brain.

In November 2017, the acting head of the Trauma Center, Joseph Spinazzola, resigned; the next month, the head of the center’s parent organization, the Justice Resource Initiative, sent a staffwide email with “JRI and #metoo” in the subject line, communicating that he had terminated Spinazzola for sexual harassment. Soon, van der Kolk was fired too. In an email to the Boston Globe, JRI head Andy Pond said van der Kolk had “created a hostile work environment. His behavior could be characterized as bullying and making employees feel denigrated and uncomfortable.” Online, fans of The Body Keeps the Score fretted that the person who had given them a language for their trauma might be inflicting trauma himself. As one wrote on Reddit, “It feels like a hiccup in my recovery. I feel like I have trusted someone who turned out to be another abuser.”

According to van der Kolk, he had left the Trauma Center in the hands of Spinazzola, a trusted mentee, during the years in which he was toiling to finish his book. Spinazzola began to harass female colleagues, van der Kolk said, but he hadn’t known about it; he just wasn’t around. He denied ever bullying Trauma Center employees. Rather, he said, the senior staff had quit with him and reassembled into several new organizations, including the Trauma Research Foundation. (JRI declined to comment on the situation.)

At the retreat, I asked van der Kolk if he finds it notable that his firing was justified using therapyspeak — the “trauma creep” that The Body Keeps the Score is sometimes accused of having facilitated. “I’m a clinician,” he said. “I’m not really interested in these kinds of sociological or political questions.” When I pressed, he got annoyed. “This stuff about cancel culture, or people saying they’re traumatized for any little thing — that’s not what my book is about. If people happen to use it for that, that’s their problem, but leave me out of it.” As in the debacle of the memory wars, he is adamant that he not be held responsible for whether, or how, his work is being misused.

Throughout the weeklong retreat, it sometimes seemed as if no event was too geopolitically vast or historically complex to be apprehended through trauma. On the first night, van der Kolk’s staff gathered with him in his suite. There was the woman who ran an international branch of the TRF focused on developing trauma workshops in the Global South, and a psychotherapist who told me she had invented the concept of “sexual grief.” Night one had gone great, they agreed, as the conversation whirled out to the Trauma Foundation’s vital work worldwide and the work remaining to be done: the war in Ukraine, global warming, the refugee crisis, famine, guerrilla violence, the great wheel of history screaming out for increased trauma intervention. It was hard to think of a problem to which trauma therapy wouldn’t be the answer.

Over the course of six days, in small groups, in evening exercises, over lunch, many people described their pain. One night, we stood in a circle as everyone took turns stepping into the center; then the group would say their name “with delight at their existence.” It was supposed to replicate the feeling of being a child basking in their parents’ love. People cried. I cried. The next day, Licia Sky led us outside to walk across a field toward a partner while keeping eye contact. One man thanked his activity partner, whom he’d hugged at the end, for a healing experience. When his partner took the mic, she said she had felt coerced into the hug, then burst into tears. It was like something else had happened to her, she said. Later, I chatted with a Canadian minister who was there to improve his counseling skills. “The science is interesting,” he said, lowering his voice. “But I’m starting to wonder if I’m … traumatized enough to be here.”

On the last day, I spoke with one of the retreat’s assistants, a German physiotherapist with sad, kind eyes. He had been terribly abused as a child, he told me. He spent years in pain. But understanding the new science of trauma through van der Kolk’s work had changed his life. He explained how trauma can be trapped in the body as a reflexive wince stuck in time — manifesting as a shoulder spasm, for example, when someone hears a word that reminds them of the traumatic event. He used to have those, he said, but not anymore. We’re at the beginning of a new scientific epoch, he told me, of understanding the truth about trauma: Finally, humanity can hope to free itself from the cycles that have dragged us through eons of war, violence, and poverty. Someday soon, he told me, finally, we will all become clean.