The American economy keeps performing better and better. Oddly, so too does Donald Trump’s polling. It is historically difficult to find a period of time in which an incumbent president, absent a major scandal or failed war, has suffered such miserable public approval in the face of widespread prosperity.

But for all the questions this predicament raises, it should at least put to rest one persistent question: whether the source of Donald Trump’s appeal is the immiseration of the working class.

The idea that Trumpism grew out of the shuttered factories of the Rust Belt, or perhaps the stagnating job market following the Great Recession, first took hold around eight years ago. Reporter Jeff Guo found links between areas supporting Trump in the Republican primary and “deaths of despair.” The left-wing commentator Thomas Frank wrote, “Could it be that all this trade stuff is a key to understanding the Trump phenomenon? … We cannot admit that we liberals bear some of the blame for its emergence, for the frustration of the working-class millions, for their blighted cities and their downward spiraling lives.”

When Trump surprisingly defeated Hillary Clinton, leftists used the event to proclaim the repudiation of Democratic Party’s entire program. “White working- and middle-class fellow citizens — out of anger and anguish — rejected the economic neglect of neoliberal policies and the self-righteous arrogance of elites,” wrote Cornel West. “Trump’s election was enabled by the neoliberal policies of the Clintons and Obama that overlooked the plight of our most vulnerable citizens.”

But it was not only the left that upheld this economy-centric understanding of the Trump phenomenon. The mainstream, too, believed Trump’s supporters had been left behind by the economy. The New York Times’ Election Night report on Trump’s victory in 2016 described his supporters as “a largely overlooked coalition of mostly blue-collar white and working-class voters who felt that the promise of the United States had slipped their grasp amid decades of globalization and multiculturalism.”

Analysts who closely studied the Trump vote cast doubt on this premise. Social issues, not economics, formed the main motivation for voters switching from Barack Obama in 2012 to Donald Trump in 2016.

But the economy-centric interpretation never died. One reason is that it was difficult to cleanly pull apart the effects of culture from the effects of economics. Educational polarization has been the master trend in politics, not just in the United States, but across the developed world. And because education and income are linked, it’s not always easy to see which factor is driving the trend and which is merely being pulled along for the ride. If Trump is losing votes in a wealthy, college-educated town and gaining them in a blue-collar town, the cause of the shift isn’t obvious.

A second reason the economic account of Trumpism has stayed around is that it flatters his supporters. Describing a phenomenon as a populist revolt against economic elites is not merely a description, but a moral indictment that allows the the Democratic Party’s critics to lambast it as a tool of the elite.

“We’re endlessly lectured by progressive elites in politics and the media about how GREAT the Biden economy is,” claims conservative pundit Batya Ungar-Sargon. “It actually is great — if, like the elites lecturing you, you own a house and have a stock portfolio. But for most Americans who live paycheck to paycheck, it’s awful.”

American Compass, a right-populist think tank, recently published an analysis purporting to show the “upper class” had become overwhelmingly Democratic. The report was eagerly embraced by the party’s left-wing critics, like Samuel Moyn:

But American Compass’s definition of “class” was not quite what you’d think. It combined educational status with income. And the survey grouped respondents who did not report their income solely by their educational status, so that those who have an advanced degree but did not report their wages were defined as “upper class.” That definition includes, for instance, teachers — a majority of whom hold advanced degrees — and many other workers whom we wouldn’t intuitively describe as “upper class.”

Finally, and most frustratingly, the economic trends of Trump’s term, and then the couple years that followed, also made it hard to disprove the economic interpretation. The trajectory of the economy did not change when Trump took office, but the continued economic expansion pushed down the unemployment rate to a level that finally began to drive up wages for blue-collar workers. The boom came to a halt in 2020, but its effects were immediately replaced by generous economic aid.

Many Democrats adopted versions of this belief and hoped that Biden would undercut elements of Trump’s economic appeal by both co-opting his nationalist trade strategy and re-creating the high-pressure labor market of his first three years. Democratic senator Chris Murphy of Connecticut wrote an Atlantic column in 2022 arguing that neoliberal economics had alienated the working class from Democrats, but Bidenomics would win it back:

In largely rural parts of the country, Americans who feel left behind by neoliberal economics want to regain control over their economic destiny.

Luckily, President Biden’s first two years of accomplishments provide Democrats with an opportunity to sell a new, winning message of actionable economic nationalism — the antidote to the failures of neoliberalism. Biden has already passed three major legislative acts that show how economic nationalism works in practice. First, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law set about the work of rebuilding America’s roads, rails, and power lines, which will attract lost jobs back to America. Second, the CHIPS Act restarted the American microchip industry, as evidenced by the recent announcement of a $20 billion, 3,000-job microchip factory in Ohio. Finally, the Inflation Reduction Act supercharged the domestic renewable-energy industry; one estimate suggests that the law will create 9 million new jobs over the next decade.

The policy element of the plan was undeniable — Biden had kept Trump’s tariffs in place while building out extensive subsidies for manufacturing in left-behind towns. His “blue-collar blueprint” would win back those workers who had been abandoned by neoliberalism.

The plan was foiled, at least initially, by the post-pandemic inflation surge. Workers’ rising wages couldn’t keep pace with rising prices in 2021 and 2022. No wonder workers struggling with high costs longed for Trump’s return. Trump-era prosperity had given way to Biden-era inflation. So as of a year ago, it was still possible to squint at Trump’s support base and see economics as the primary underlying cause.

But those economic conditions no longer hold. Inflation has finally returned to normal levels, and the job market remains red-hot. Wages have been running ahead of price levels for the last year.

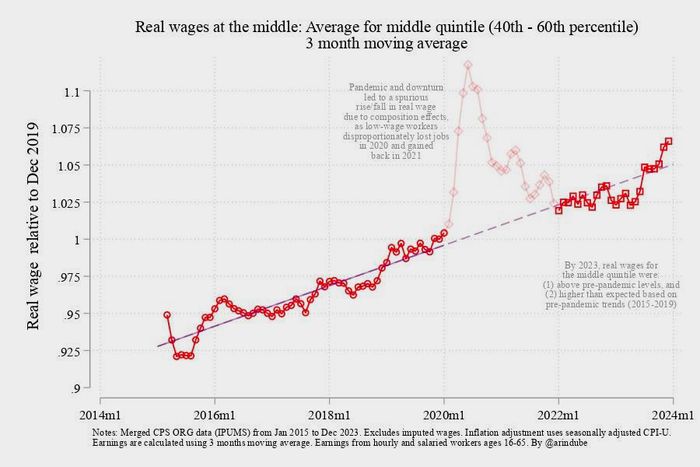

Arindrajit Dube, an economics professor at University of Massachusetts Amherst, recently detailed how the recovery has produced real wage growth. After inflation and the clawback of COVID-era fiscal support hurt pocketbooks through the first two years of Biden’s term, inflation-adjusted wages are now growing faster than the pre-pandemic trend:

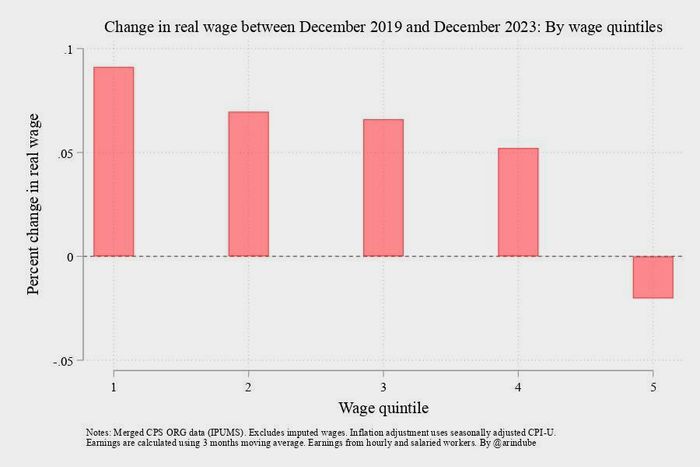

And contrary to the complaint that only the elite have benefitted, Dube confirms that just the opposite has occurred. The lowest-earning households have gained the most, while the most affluent have lost purchasing power:

This has not only failed to dent Trump’s standing, it’s coincided with an increase. Over the last year, a period when the economy has surged, the former president has gone from tied with Biden to two points ahead. It is understandable that public sentiment would lag behind economic conditions. But the news narrative about the economy has turned sharply positive in recent months, and feelings about the economy have turned north as well. Even so, Biden’s polling continues to worsen.

There’s enough time for conditions to sink in and lift Biden’s approval. But at this point, a return to circa-2020 polling conditions (Biden winning by 4.5 percent) would be about a best-case scenario.

All this is to say that delivering broadly shared prosperity for the working class has done nothing so far to reduce the appeal of Trumpism. His appeal is not born of desperation or despair. Whatever alchemy produced the Trump cult, money alone will not dispel it.