This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

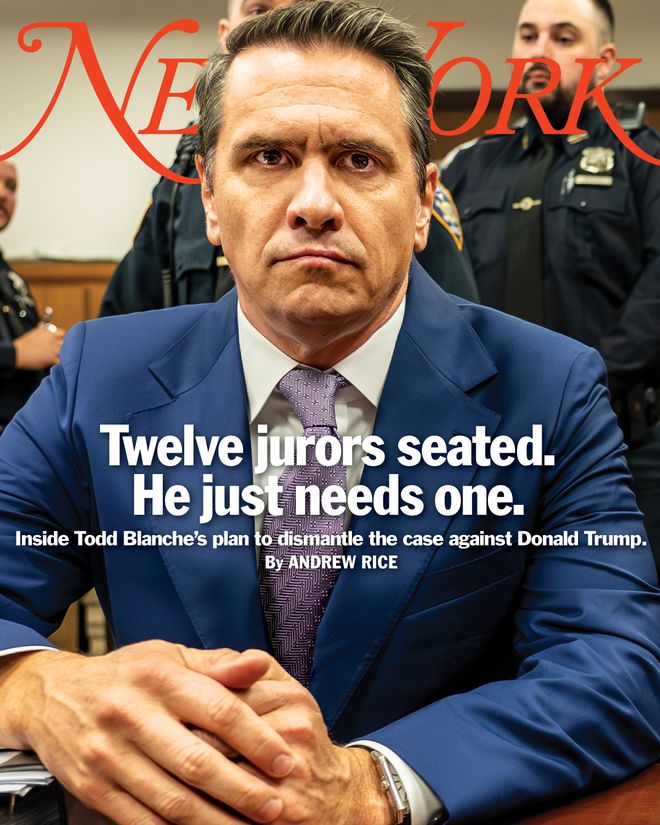

Todd Blanche was looking for his man. Or it could be a woman, but probably not. For a criminal-defense attorney, picking a jury is about profiling: an intuitive art. And so, on the second day of the most important trial of his life — and maybe of American political history — Blanche was looking for clues in demography, finding meaning in posture, flinches, intonation, and pregnant pauses. There was so much to distract him from his task, starting with the demanding defendant sitting to his left and the hue and cry that surrounds his traveling courthouse circus. Difficult as it was, Blanche had to tune out the noise and home in on the signals emanating from 18 citizens sitting in a jury box to size up whether any of them might be the one.

When Blanche, a former federal prosecutor, joined Donald Trump’s defense team about a year ago, it was widely assumed that the former president’s prospects were, both politically and legally, hopeless. Instead, Trump has survived — and, at least in the short term, benefited from — his legal struggles. Outside court, he has used his claims of persecution to rally Republicans. Within the legal system, he is now on the verge of escape thanks to a combination of lucky breaks, errors by his adversaries, a favorable tilt in the Supreme Court, and the effectiveness of Blanche and a group of other quietly adept criminal lawyers. Even as Trump smashes away at a “broken” justice system, Blanche — who is handling three of Trump’s four criminal cases — has tried to turn that system’s processes to his advantage, litigating, appealing, and otherwise gumming up the works until November. The success of the clock-chewing strategy has been maddening to Trump’s opponents, who are desperate to see him held accountable for something.

In This Issue

Barring an unexpected turn of events, the only trial Trump will face this year is this one, the case brought by Manhattan district attorney Alvin Bragg. It happens to be the easiest one for his defense team: a relatively small-time, first-term potboiler involving Michael Cohen and Stormy Daniels. In a city where people danced in the streets when Trump was defeated, the chances of an outright acquittal are dim. But a hung jury is plausible. “You just need one juror who is sitting back there going, This guy is a piece of shit, but this is political,” says an attorney who is familiar with the case. If that were to happen, Judge Juan Merchan would have to declare a mistrial, which Trump would surely spin into a victory, allowing him to go into November crowing about how, even in hateful New York, he was completely, totally, unquestionably exonerated. A conviction, though, could be fatal: In polling, a significant number of Trump’s supporters have said they would draw the line at voting for a felon. Thus both the trial and the election could come down to a single voter. Blanche needed to find his holdout juror.

First up today: the candidate in Seat 10. The judge had put strict limits on the process to protect jurors from reprisal. Seat 10’s name was known only to the lawyers, and he was referred to by his number. He was a middle-aged man in a gray blazer. He went through a rote list of questions. He was originally from Dallas and worked in finance. He said he liked to play golf. So far, so good for Blanche.

In response to a series of questions about his media habits, Seat 10 said he read The Wall Street Journal and watched Fox News. He listened to Barstool Sports podcasts. When he got to question 21a, which asked about bias relating to “political, moral, intellectual, or religious beliefs,” the prospective juror hesitated. He said that in his world of finance, “a lot of people tend to intellectually slant Republican,” and he added he was a native of Texas. “You know, growing up with a bunch of family and friends who are Republican, it’s probably going to be tough for me to be impartial.”

For Trump, he was too good to be true. The judge dismissed him, and Seat 10 respawned with another prospect, a 30-something uptown lawyer with fashionably tousled hair. Bad trade.

In his eight years as a prosecutor with the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York, Blanche performed this selection exercise countless times, albeit from the other side of the room. The people who worked with him there, the lawyers who know him best, say he is unusually skilled at getting in the heads of jurors. “He’s an extraordinary trial lawyer,” says Hadassa Waxman, who worked under him in the violent-crimes unit and is now a white-collar defense attorney. Another former colleague, Kan Nawaday, says Blanche is “very good at reading people” — not just jurors but cops, witnesses, informants, and other types you encounter when dealing with street crime. Blanche, whose father was a preacher, thinks of himself as an outlier in the upper echelons of his profession.

“I went to night law school. Nobody in my family ever even thought about going to law school,” Blanche told me in one of a series of conversations this spring as he prepared for trial. “I knew that the only way I could do it was, I’ll work harder. That’s kind of been my entire legal career.”

Over the first four days of the trial, Merchan brought in two groups of 96 potential jurors. Each time, about half walked out after they were posed a first question, which was whether they felt they could impartially judge Trump. That left Blanche to determine which ones were genuinely open-minded and which were liars. Casting is important to Trump, and Blanche looks the part: A college baseball and basketball player and a midlife triathlete, he wore a snug-fitting suit that accentuated his broad shoulders, and he kept it tightly buttoned. He used his time during the questioning process to carefully, genially probe for evidence of strong negative prejudice, telling prospective jurors it was all right to confess their opinions. Several swore they had no view of Trump, only to be confronted, after a quick search of their social media by the defense, with photos of anti-Trump memes or, in one case, a post that read, “Get him out and lock him up.” The judge excused some of them for cause. To get rid of others, including the uptown lawyer, Blanche had to use up his limited number of challenges.

One man, a resident of Battery Park City, said he had read three Trump books, including the lesser-known work Think Like a Champion, which inspired the former president to give him an approving nod. Another, a loquacious retired Correction officer, said he remembered how Trump had treated the Central Park Five. But he also said he had a lot of friends from his neighborhood who had done time, and he knew that sometimes cooperating witnesses told the police whatever they wanted to hear. Later there was a law-enforcement officer who loved the Rangers and used a flip phone. They all sounded like they might listen to the defense, which must have worried the prosecutors, who struck them.

“I find him fascinating and mysterious,” said a resident of the Lower East Side who was born in Puerto Rico, sounding in awe of Trump. “He walks into a room and he sets people off.” He made it onto the jury only to be excused by the judge after prosecutors raised the possibility that he had previously been arrested for tearing down political signs.

Somehow, by the end of the week, Merchan had managed to swear in 12 jurors and six alternates. They included a young software engineer who lives with roommates, a charter-school teacher, an investment banker who follows Michael Cohen on X, a Lebanese retiree who likes to meditate, and a woman in the apparel business who said she found Trump “very selfish and self-serving” but nonetheless promised to be fair.

Among that group, Blanche was hoping he could find someone who, while maybe not a fan of Trump to begin with, was willing to be persuaded. Someone like himself, in other words. Blanche was once a registered Democrat, but by his own account, he has grown to sympathize strongly with Trump’s claim that he is being railroaded. His conversion to the cause has had consequences: To take on Trump as a client, Blanche had to quit the Wall Street firm where he was a partner. Some of Blanche’s former colleagues understood the decision, believing, like him, that this is simply what lawyers do; others thought that while everyone is entitled to a lawyer, no one has to choose to work for Trump.

If Blanche loses any of Trump’s criminal cases, and his client the election, it will probably mean the end of his career in the elite world of Big Law that he worked so hard to join. Many of his former colleagues, though, are more worried about what will happen if he wins. “I love Todd, but I think what he is doing is crazy and I told him myself,” says Waxman, who adds, with gallows humor, “If, God forbid, Trump becomes president again, we can thank Todd for bringing down the Republic.”

There are some people who represent Trump who are terrible lawyers,” says Aitan Goelman, a former prosecutor in the Southern District. “There are some people who represent Trump who are terrible people. And Todd is neither of those things.” They first met in the late 1990s when Blanche was a young paralegal who had taken a job in the district’s lower-Manhattan offices. “He was very organized, worked his ass off, he had very good judgment,” recalls Goelman. Before long, he was insisting that Blanche work with him on every trial. Then word got around and everyone started wanting him on their cases too. Blanche was putting in long, intense hours in the courtroom. At night, he was taking classes at Brooklyn Law School.

“I wanted to be a prosecutor so badly,” Blanche told me. The prosecutors at the Southern District were taking on the biggest cases of the time, trying Al Qaeda terrorists and Wall Street fraudsters. The office had a lofty institutional ethos and a reputation as a proving ground for high-powered lawyers. Blanche was self-deprecating about his lack of an Ivy League pedigree. He would joke about it with his colleagues, referring to some of them as “Harvard-Harvards.”

Blanche was born in 1974 in Colorado, where his father, Richard, operated a church in the family’s house. Four days a week, his father would meet with his small congregation, the Faith Bible Fellowship, in the basement. When neighbors complained, there was a zoning dispute and a lawsuit. Richard was cited multiple times for contempt, and he vowed to preach from prison rather than comply with the authorities. He appealed the zoning decision all the way to the Colorado supreme court, which ruled against him. In 1987, the Associated Press reported that the family was moving to Gainesville, Florida. “We’re going to live in a tent until we can find a home and another church,” Richard said. His son recalls that they actually rented a small apartment.

After that, the family moved around. Todd attended a military boarding school in New Mexico, where he was a standout athlete. He was on the baseball and basketball teams at Beloit College, a Division III school, before transferring to American University in Washington, D.C., to be closer to a girl at Catholic University, Kristine, whom he had met on a trip to Australia. “He was very snarky and irreverent in the best possible way,” says Shane Hedges, his best friend at American. Blanche wasn’t religious like his father. He liked to needle Hedges, a Young Republican. “He was a Democrat for a good chunk of his life,” Hedges says. “Very similar to Trump.”

Todd and Kristine got married when he was 20. At an age many lawyers are solely focused on their careers, he had two young children and was living on Long Island. Still, he was tirelessly dedicated to the day-to-day grind of implementing the law.

“He was like the wonder kid,” recalls Mimi Rocah, the Democratic district attorney of Westchester County, who first met Blanche when she was a federal prosecutor and he was a paralegal. After getting his degree and clerking for a couple of judges, Blanche returned to the Southern District as a prosecutor in 2006. While some of his colleagues were clamoring to get on the terrorism or securities-fraud units, where their cases make headlines and careers, Blanche headed for the violent-crime division. He wanted to be in the courtroom all the time, putting criminals in prison.

The division was located on the first floor of the Southern District’s headquarters, tucked away behind the front security desk, and it tended to operate without much oversight from upstairs. He soon found that, for this job, he possessed capacities that some of the Harvard-Harvards lacked. He could talk to anyone like an equal, and he was nimble on his feet in a courtroom, though it was also true that the system was tilted in his favor, as he faced defendants who didn’t evoke much sympathy.

“You’re dealing with gangs that terrorize neighborhoods — killers,” said Randall Jackson, an attorney who was part of Blanche’s cohort in the office. “Really bad guys. And so Todd, I think, is a person who as a prosecutor was very invested in wanting to do hard, good work for the community.” I asked if that meant he would describe Blanche as a moralist.

“I think there was something that supersedes that,” Jackson replied. “The morality that I always observed him to be most invested in is a sort of institutional morality.”

After a few years, many prosecutors cycle out of the Southern District, leveraging their experience and contacts to move to higher-level positions at Main Justice in Washington or into lucrative jobs in the private sector. (People in the office call the securities-fraud unit, which often deals with banks and the white-collar criminal-defense bar, the “departure lounge.”) Blanche stuck it out for eight years, longer than many. He became co-chief of the violent-crimes unit and then moved to a top position in White Plains, where he and Rocah ran the district’s branch office. But his kids were going to college, so he made the leap to private practice, first at WilmerHale and then at Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft, a law firm with the whitest of shoes.

At Cadwalader, Blanche was considered a solid attorney but not a rainmaker. “Nobody knew Todd existed before Trump hired him,” says a Manhattan criminal-defense attorney who has done many high-profile trials. That was partly a function of the work. In white-collar criminal defense, your clients are mostly trying to avoid indictment or cut a deal. If you end up in a trial, something has gone terribly wrong. It can be difficult to find ways to advertise your skills and build a reputation. During a decade of private practice, Blanche was involved in only one criminal trial, in Pennsylvania, and even there his role was limited to arguing a narrow forfeiture issue. Other criminal defenders told me Trump was taking an enormous risk by placing his fate in the hands of someone who had never had to tear apart a cooperating witness or perform any of the other tactics criminal defenders use to sow reasonable doubt.

In 2019, a former colleague from the Southern District contacted Blanche and told him he was looking for a lawyer who would be willing to take on a politically radioactive client: Paul Manafort. This marked his introduction to Trump world, where there is always plentiful work for criminal-defense attorneys. Manafort, a former manager of Trump’s 2016 campaign, had already been tried and convicted of federal tax evasion and other financial crimes. He was serving a seven-and-a-half-year federal-prison sentence. Cyrus Vance Jr., the Manhattan district attorney at the time, had brought his own state mortgage-fraud prosecution as a sort of fail-safe in case Trump gave Manafort a pardon. Blanche took the New York case and convinced a judge to dismiss it on double-jeopardy grounds. “He crushed it,” says a former senior official in the DA’s office. Trump did pardon Manafort, but the New York decision held up on appeal.

“He focuses on the law, but he looks through the filter of what’s going on in the public domain,” Manafort says of Blanche. “Because everything Trump related is political.”

After Manafort, Blanche represented Igor Fruman, an associate of Rudy Giuliani’s who pleaded guilty to campaign-finance-related crimes. Then he was retained by Boris Epshteyn, a securities lawyer, conservative television commentator, and a Trump campaign adviser who played a coordinating role in the president’s efforts to submit alternate slates of electors in 2020; two years later, prosecutors investigating January 6 seized his cell phone. (Epshteyn has not been charged in the case, though it has been publicly speculated that he fits the description of “Co-Conspirator 6” in Trump’s Washington indictment.)

After unwillingly leaving office, Trump had retreated into relative seclusion at Mar-a-Lago, where he kept counsel with a handful of loyalists. One of them was Epshteyn, whom he came to rely on as a legal adviser as investigative pressure on him intensified. In addition to the federal January 6 investigation, in Georgia, Fulton County district attorney Fani Willis convened a special grand jury to consider evidence that Trump had engaged in a conspiracy to steal the election. Trump was also fighting with the National Archives over classified documents he was suspected to be hoarding. And there were the civil cases to deal with, including the New York attorney general’s office’s civil-fraud lawsuit against Trump and his business and two separate actions brought by journalist E. Jean Carroll for defamation.

Trump deputized Epshteyn, who had been an associate at Milbank LLP, to assemble his legal team. They approached many of the most prestigious law firms in New York and Washington, D.C. Although Trump has a reputation as a skinflint, in this instance payment was no issue because he could draw on campaign donations from his supporters. (Trump’s PACs have reportedly spent more than $100 million on his legal fees since he left office.) But white-shoe law firms are risk averse, with many worried about backlash from corporate clients, and the best criminal-defense attorneys can afford to be choosy.

“I would not represent Trump because I have a conflict,” says the prominent criminal-defense attorney Gerald Lefcourt, who was not approached to do so. “The conflict being I so profoundly disagree with everything he stands for.” Lefcourt had previously represented sexual predator Jeffrey Epstein.

Epshteyn had asked Blanche to help him conduct the search, and Blanche gradually came around to the idea that he should join the legal team himself. Epshteyn and Manafort vouched for him with Trump. The former president called up Blanche in February 2023, catching him on a family ski trip over Super Bowl weekend. Later, they had a three-hour dinner at Mar-a-Lago, the first of many such meetings, over which they built a rapport. Trump promised Blanche that he was going to make him famous. Within two months, they were sitting together at a defense table in Judge Merchan’s courtroom in Manhattan as Trump pleaded not guilty to 34 felony counts of falsifying business records to cover up hush-money payments made to Stormy Daniels during the 2016 campaign.

The management at Cadwalader had given Blanche a choice: his partnership or Trump. So he quit. Blanche could not believe his professional community had no problem with lawyers representing the Jeffrey Epsteins of the world but considered the once-and-possibly-future-president beyond the pale. “I found incredible hypocrisy in the way that Trump was being viewed and looked at by my peers in New York City,” Blanche told me. “And so I said, ‘Let’s go — I’m going to do the case.’”

Trump has been under criminal investigation almost from the moment he entered politics, and he has churned through so many lawyers at this point that you can predict the arc of their employment. They come and they go, often in anger or disgrace. With uncanny frequency, they end up becoming investigation targets themselves. Eight Trump-affiliated attorneys were named in the Georgia conspiracy indictment, and three so far have pleaded guilty.

“It’s tough because he puts you in bad positions,” says one of Trump’s former attorneys. “He asks you to do things that cross boundaries.”

“Trump only knows out-of-bounds,” says Ty Cobb, a Washington defense attorney who was special counsel to Trump in the White House during Robert Mueller’s investigation of Russian interference in the 2016 election. Trump would often ask Cobb and the other lawyers who were dealing with Mueller why they couldn’t be more like Roy Cohn, the McCarthyite intimidator who served as his early mentor. Cobb, who has since compared Trump’s behavior to that of a “mob boss,” has a framed sign reading YOU’RE NO ROY COHN over his desk. “I look at that and swell with pride,” Cobb says.

In exile, though, Trump suffered from having a surplus of Cohn clones, lawyers who competed to do whatever he wanted. To begin with, there was Epshteyn, who has hovered amorphously over all his legal proceedings. At the Carroll hearing in January, he identified himself to the judge as Trump’s “in-house counsel.” Then there was Christina Bobb, a right-wing lawyer and TV personality who came under FBI investigation after she signed a sworn statement about a “diligent search” for classified documents at Mar-a-Lago that turned out to be false. (Bobb was not charged, and she was hired in March for a position at the Republican National Committee.) Next was Alina Habba, a former New Jersey parking-garage-company lawyer who met Trump through his Bedminster golf club. She was sanctioned by a federal judge in Florida after bringing a lawsuit against Hillary Clinton and other Democrats on Trump’s behalf. The judge called it “completely frivolous, both factually and legally,” and fined them $1 million.

Blanche seems to have convinced himself that it is possible to represent Trump without becoming a Trump lawyer. When he arrived, Trump’s legal defense was in an especially dire state of disarray. One lawyer dealing with the classified-documents dispute, Evan Corcoran, had been forced to give testimony and evidence to a grand jury under the crime-fraud exception to attorney-client privilege, which is as bad as it sounds. Other parts of the legal team were feuding. After the FBI raided Mar-a-Lago, Trump turned to criminal defender Tim Parlatore, who had come recommended by former New York police commissioner (and Trump-pardon recipient) Bernie Kerik. For the New York case, Trump hired Joe Tacopina, a lawyer best known for defending sports and hip-hop stars, who had been referred by Kimberly Guilfoyle. But Parlatore and Tacopina hated each other, bad blood that dated back to a lawsuit involving Kerik.

Parlatore eventually quit and started giving interviews in which he dismissively referred to Epshteyn as a “banking-transaction lawyer” and said his meddling was hurting Trump. “All of the legitimate lawyers have been replaced with people who will do what Boris says,” Parlatore told me. (In a statement, Trump campaign spokesman Steven Cheung said his boss currently has the “most experienced, qualified, disciplined, and overall strongest legal team ever assembled.”)

Over the course of four months last year, Trump was indicted in quick succession in New York, Washington (over January 6), Florida (over the documents), and Georgia. Blanche originally came in to handle the New York case, joining Tacopina, who had a track record of courtroom wins for celebrity clients, such as getting a conviction overturned for rapper Meek Mill. A third attorney on the case, Susan Necheles, was a veteran criminal-defense lawyer with a reputation for tenaciously challenging prosecutors. Necheles has stayed on the case, but Tacopina was asked to take over the first of the two Carroll trials, on which he ran afoul of Trump by advising his client not to testify. Trump lost a $5 million verdict and Tacopina left the team, handing the second Carroll hearing in January to Habba, who allowed Trump to (briefly) take the stand, quarreled with the judge, and had trouble with basics like introducing evidence. The second verdict was far worse: $83 million.

While Trump was going down in flames in these civil cases, Blanche was concentrating on the criminal trials, in which the stakes were more than just monetary. He established a new firm, Blanche Law, which is managed by his wife, a holistic-medicine practitioner, and lists a “virtual office” address in the Financial District. Effectively, during the Manhattan trial, he has been working in Trump’s building at 40 Wall Street. Save America, a Trump PAC, has made around $3 million in payments to Blanche Law since last April. But Blanche’s relationship with his client is intertwined with his campaign in ways that go beyond its finances. He and his wife bought a house in Palm Beach Gardens late last year. Partly they want a place for their children to visit — at the age of 49, Blanche is a grandfather — but it is also convenient to Mar-a-Lago. Blanche went there to attend a celebration on the night of the Super Tuesday primaries. He is now a Republican.

In consultation with Trump and Epshteyn, he has worked to build out a defense team. One attorney involved likens the current setup to “a collaborative law firm” put together on an emergency timetable. They have prioritized a professional type. The guiding principle may best be described as: No more Habbas. Blanche is not the only one who had to quit his job to join the defense. So did Chris Kise, a well-connected Florida lawyer who is on the Mar-a-Lago case, and Emil Bove, a former co-chief of the Southern District’s terrorism unit who brought with him expertise in national security and classification issues. Others were able to come aboard because they have boutique firms or are solo practitioners. John Lauro, a former Brooklyn federal prosecutor who has a firm with offices in New York and Tampa, is splitting the work with Blanche on the January 6 case. Steve Sadow, an Atlanta attorney, has taken the lead on the Georgia conspiracy indictment. That state case has been handled autonomously by the local lawyers, so far with great success — and with help from Willis, who, for some reason, hired a lead prosecutor with whom she was romantically involved and steered the case right into a ditch.

Blanche effectively took out two of the other three cases through procedural maneuvering. The January 6 prosecution brought by special counsel Jack Smith — which at one time looked like it would go to trial this spring — was stalled by a pretrial appeal over a claim of presidential immunity that has gone all the way to the Supreme Court. In the documents case, Blanche is seeking to force the intelligence community to turn over classified information in discovery, a time-consuming process made even slower by the unusual deference the judge, Aileen M. Cannon, has shown the defense.

In March, I watched Blanche argue a pair of motions before Cannon at the federal courthouse in Fort Pierce, Florida. Outside, a band of flip-flop-wearing protesters held an all-day MAGA jamboree, tailgating and doing the “Y.M.C.A.” dance. Blanche told me that when Trump’s motorcade rolls through town, people on the street look up and wave and he thinks to himself, That’s my juror. At the defense table, Blanche covered his microphone to whisper back and forth with Trump. They laughed a lot. Twenty or so feet away, Smith sat thin and straight as a needle, staring intensely at the defense table, looking as if he wanted to call for the rack.

It was easy to guess why the defendant was relaxed: He had appointed the judge. Still, Blanche was pushing their luck with these motions. He was asking Cannon to determine that Trump could legally take the documents, simply because he did so while president, and thereby to dismiss the case. That seemed a bit much to ask, even of this judge. Still, Cannon wanted to hear a full day of argument, burning more time off the clock.

“Presidents since George Washington have taken materials from the White House,” Blanche argued. A prosecutor from Smith’s team got up and said that was an absurd misinterpretation of the records law, which at any rate did not cover the flagrant behavior alleged in the case. Trump was charged with taking dozens of documents pertaining to military operations, nuclear capabilities, and other state secrets out of the White House, stashing them in boxes, and enlisting his staff to help him deceive the government. “I know we’ve talked a lot about the law, and it’s very worthwhile,” Cannon said at the end of the five-hour hearing. With that weak summation, she adjourned, and Trump sped back to Mar-a-Lago. There would be more jawing to come.

Later that afternoon, Blanche was in a chipper mood when I met him at a hotel bar near the Palm Beach airport. His client, he said, deserved the full protection of the legal process in all of its slow-moving glory. But that was only part of the reason Blanche left his job to take on Trump as his primary client. He enjoyed being part of the biggest trial there is. “You wouldn’t want to represent the president of the United States in a historically unprecedented case?” Blanche asked with a grin.

Lawyers do not have to believe their client, or believe in their client, but they do have to voice their client’s argument. Some of the Trump team’s attempts to undermine the four indictments have identified real weaknesses, arguments his lawyers have every right to ask the courts to hash out. Others are, frankly, ridiculous. Blanche and his team have filed briefs that suggest there may be something to Trump’s claims about a deep-state conspiracy or the idea that the election was stolen. The immunity appeal advances a staggeringly broad claim that would effectively make it impossible to prosecute an ex-president unless he had first been impeached and convicted. At an appeals-court oral argument in January, another of Trump’s lawyers conceded such immunity would logically extend to ordering political assassinations.

As the Manhattan case moved toward trial, Blanche’s court filings took on an aggressive tone that echoed his client’s rhetoric. Blanche wrote a public letter to Bragg — another former Southern District colleague — accusing him of engaging in “corrupt tactics” and “tyrannical conduct.” He seized on Bragg’s disclosure that his office had belatedly received thousands of pages of documents relating to Michael Cohen previously held by federal prosecutors, and he filed a motion for sanctions on Bragg alleging “widespread misconduct.”

That led to a hearing on March 25 in which Merchan, rather than scolding the prosecutors for the discovery lapse, turned his fury on the defense. “You are literally accusing the Manhattan district attorney’s office of engaging in prosecutorial misconduct,” the judge said to Blanche, “and trying to make me complicit in it.” (When I texted Parlatore, who has continued to heckle the legal team from the sidelines, to ask how he thought things went that day, he wrote back: 😂.)

The March hearing made it clear to all that Blanche’s delay strategy had reached the end of the line. Trump responded the only way he knows. With Blanche standing behind him, he staged a press conference at 40 Wall Street, where he stood in front of a bank of flags and inveighed against “Biden and his thugs” and his practice of “lawfare,” his favored term for any legal action against him or his allies. He attacked the “tremendous corruption” of the Manhattan DA’s office and Merchan, a “Democrat judge.”

Trump has spent his life rolling over people who displease him, but there are serious consequences to picking a fight with a judge in a criminal case, who shapes the trial and can hold a defiant defendant in contempt. But Trump heedlessly continued to blast away at Merchan on Truth Social, going so far as to target the judge’s daughter, a Democratic consultant, over purported anti-Trump posts to a social-media account that turned out to be phony. After Trump’s initial round of attacks, Merchan imposed a gag order, preventing the defendant from criticizing witnesses, jurors, prosecutors, court employees, or their families. Trump kept going, and Blanche did not get him to stop. Instead, he filed a recusal motion that questioned the daughter’s political work.

Some of Blanche’s old friends were dismayed by his supporting role in Trump’s attacks. “What bothers me is these are the arguments Trump has been making all along because his No. 1 goal is to discredit the system that is trying to hold him accountable,” says Rocah. “I would say it is shocking to see a lawyer be a part of those arguments, let alone a former prosecutor.” (Rocah stresses she is speaking for herself, not as an elected officeholder.)

On the first day of jury selection, Trump rose a beat slower than everyone else when Merchan entered his fluorescent-lit courtroom. As his first order of business, the judge curtly denied the defense’s recusal motion. Prosecutors filed their own motion to hold Trump in contempt, accusing him of violating the gag order, introducing as evidence a series of recent posts on Truth Social maligning Daniels, Cohen, and Merchan himself, whom Trump had called “my current New York disaster.”

Blanche stood up and claimed Trump had merely been defending himself. “It’s not as if President Trump is going out and targeting individuals,” Blanche said. “He’s responding to salacious, repeated, demonizing attacks by these witnesses.” The judge scheduled a hearing on the motion for April 23. For now, the penalty for contempt would likely be a modest fine, but further violations could, in theory, land Trump in a jail cell.

During a pair of civil trials over the past year, judges repeatedly admonished Trump’s lawyers for failing to control him. But Blanche told colleagues he liked having Trump in court at hearings because he had to learn how the criminal-justice system worked. “If there is someone out there who can be a Trump whisperer, because that’s what you need, I think Todd has a chance,” Blanche’s former colleague Nawaday says.

There is only so much you can whisper, though, to a client like this. On the second day of jury selection, Merchan issued a sharp warning after he saw the former president “audibly uttering” and “gesturing” as a juror was questioned about her political sympathies. “I won’t tolerate that,” Merchan said. “I will not have any jurors intimidated in this courtroom.”

Once the trial begins in earnest, it’s not hard to see how Blanche will proceed: by trying to make the prosecution look penny-ante and politically motivated. The alleged crime involves a $420,000 “retainer agreement” between Trump and his then–personal attorney Cohen that was reportedly meant to cover a payoff Cohen had made to keep Daniels from selling her story to the National Enquirer or some other tabloid. But in New York, the crime of falsifying business records is only a misdemeanor unless it was committed in connection with another felony, and it’s not clear that one was involved. It seemed to many — even some lawyers who want to see Trump prosecuted — like a small holding in Trump’s portfolio of misdeeds. “I’ve got a great affinity for the rule of law,” says Cobb. “What he did in the New York case is Mickey Mouse stuff.”

Unfortunately for Blanche, Judge Merchan is the only legal commentator whose opinion matters right now on the severity of the alleged crime. In February, he ruled against a dismissal motion, upholding Bragg’s underlying theory supporting the felony charges and clearing the way for a trial. That means Blanche must find other ways to undermine the case. All paths begin with Cohen, the prosecution’s most important witness. Trump can plausibly contend that he had a right to assume the retainer arrangement was legal because his lawyer said so and that whatever Cohen did with the money was his own business. Cohen may claim otherwise, but he is a felon and a proven liar. It might help Trump that, unusually, he has drawn two jurors who are lawyers themselves and may be receptive to these technical points.

Blanche’s best hope, though, might be that one or more jurors decide to acquit Trump even though the prosecution has proved its case, just because they think he’s being treated unfairly, a scenario known as “jury nullification.” “There is a method to do this,” says Jeffrey Lichtman, a lawyer who has represented Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán and the younger John Gotti, “but it requires the right type of personality.” For Gotti, Lichtman hung four federal juries in four years. The conventional wisdom among defense attorneys is that jurors start off loving the judge and sympathizing with the prosecutors. The defense lawyer’s job is to subvert the prosecutor’s authority over time and turn at least one juror around. “Is that jury nullification?” Lichtman said. “I would never admit that it is. But yeah — it is. It’s got to be done subtly. It’s got to be done carefully.”

In Trump’s case, Lichtman said, the defendant’s well-known history of sexual mischief might help him. “Look, he was getting extorted by women that he had sex with that weren’t his wife,” he says. “He was embarrassed by it and had to pay them off.”

Trump will never concede there was an affair, however, because he is running for president and because it would mean admitting he had been lying for many years. A defense attorney might be able to thread that particular needle, claiming Trump was paying for silence because he wanted to avoid scandal. But Trump has shown in previous trials that he is incapable of containing his fury, even when it is sure to hurt him. “He’s going to have to behave himself,” says the attorney familiar with the case, “which he can’t do.” Trump has been typically savage toward Daniels, whom he refers to as “Horseface.” He has also signaled he wants to take the stand, where he would likely be his own worst witness.

Even if he is found guilty, though, Trump will surely spin his defeat as validation of his claim that his opponents — Democrats, prosecutors, judges, the whole damn system — are out to get him. And from there, he will keep on running. For all Trump’s complaints that his opponents are practicing lawfare, his endgame strategy amounts to nullification on a grand scale. He’s betting that 270 votes in the Electoral College will override the verdict of any jury of 12. Once restored to power, he is sure to order his Justice Department to dismiss the federal indictments and use the immunity afforded to a sitting president to squelch any legal threats on the state level. And then he will presumably reward those who served him well.

Trump is already preparing the ground for a post-conviction campaign. The day the trial began, he posted a video to his Truth Social account, using footage of him walking into the courthouse to depict him as a legal gladiator. On the third day of the trial, Bragg’s team showed Merchan seven new social-media posts, each violating the gag order, the prosecutors claimed. One of the posts amplified a Fox News segment that allowed people to identify a nurse who was a seated juror, who promptly came in and quit. “It’s ridiculous,” said Christopher Conroy, a prosecutor from Bragg’s office, “it has to stop.”

Everyone knew it wouldn’t. Late in the day, Blanche protested that the prosecutors would not even tell him who they planned to call as their first three witnesses, a routine courtesy. Blanche tried to promise the judge that Trump wouldn’t post about any of the witnesses on Truth Social. “I don’t think you can make that representation,” Merchan said. Blanche was suggesting, like so many previous Trump whisperers, that he would be able to act as a moderating force, bringing his client around to a recognition of the reality of his situation and consequences of his conduct, if only because it was in his self-interest. But Trump has a way of co-opting his counselors. You go into it thinking you will be managing him, and soon he is managing you. And once that happens, you are just another Trump lawyer.

More on trump on trial

- Why Michael Cohen Still Misses Donald Trump

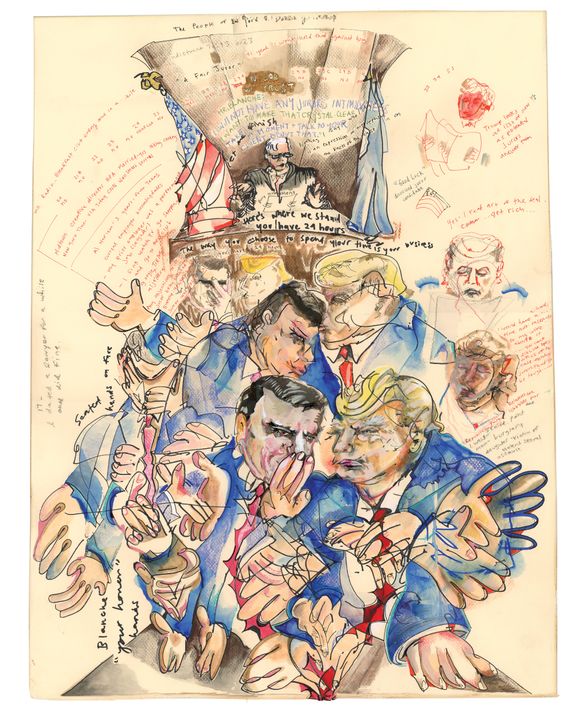

- What It Was Like to Sketch the Trump Trial

- What the Polls Are Saying After Trump’s Conviction