This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

A few days a week, Wang Juntao, a primary organizer of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and one of the world’s most renowned Chinese dissidents, travels from his home in New Jersey to his office in Flushing. He drives to the train station with the cheapest parking, then takes the PATH to the LIRR to Main Street, emerging to the whiff of fish and cigarettes and the roar of planes making their final approach to La Guardia. Skirting a stretch of street vendors and Falun Gong practitioners, Juntao cuts up 41st Avenue toward the weather-beaten headquarters of the Democratic Party of China, the organization he has led for more than a decade, dedicated to the overthrow of the Chinese Communist Party.

New York has the greatest number of exiled Chinese activists in the world, and Flushing is the effective headquarters of the minyun — the movement for democracy in the People’s Republic of China. The cause, which counted thousands of adherents in the period after Tiananmen, has dwindled in recent years to include perhaps a few hundred active dissidents. Juntao’s office is not a glamorous space. Located above a noodle shop and an internet café, it has boxes piled in the entryway, and the bathroom doubles as storage for the old-school tools of protest: megaphones, signs, paintbrushes.

Juntao usually sits in a folding chair at the head of a long table that’s covered in fraying plastic. At 64, he is impish and disarming with a prominent comb-over and an even more prominent paunch. When I went to see him in Flushing recently, he pulled back a curtain to reveal shelves of wine and liquor and offered me a cup of red. “I’m a professional revolutionary,” he said in a heavy Beijing accent. “You have to drink, you have to fight, you have to be tough.”

Being a dissident is “a miserable life,” Juntao told me after a couple of rounds. When he still lived in China, the Communist regime put him in prison twice, and for decades he’s had only limited contact with his family to spare them official harassment. “The Chinese government hijacks your relatives,” he said. “If you love them, you have to pretend not to love them.” In Flushing, some of his fellow activists were now in their 70s and 80s, and every time they gathered, there seemed to be another empty seat. Meanwhile, the news from China brings constant reminders of the Communists’ increasingly authoritarian rule, from internment camps in Xinjiang province to mass surveillance powered by facial-recognition technology. For almost three full decades in exile, Juntao has kept alive the dream of a democratic revolution in China, but he is no closer to seeing it realized.

This past March, Juntao was hit with back-to-back shocks. His closest friend and colleague in the minyun, Jim Li, who’d been by his side since before Tiananmen, was murdered. Two days later, another intimate member of their circle, Wang Shujun, was arrested by the Department of Justice and accused of spying on dissidents for China’s intelligence service. (Juntao and Shujun are not related.) When I first visited him, Juntao was reeling, trying to make sense of the killing and the alleged espionage. For months, he indulged a cloak-and-dagger theory that the two crimes were related. But even as he mourned, he remained optimistic about the push for Chinese democracy. His life, he said, has had “four ups and three downs.” Even if the movement was at an ebb, it was only a matter of time before the political tide changed. “When it’s down, you cannot make a difference,” he said in August. “But you can make a difference in yourself. And the difference in yourself will determine if you’ll have a chance when it’s up.” Soon, he predicted, President Xi Jinping would lose enough support that he would face a backlash.

In the Chinese diaspora, that kind of faith is rare. Many would call it quixotic. In October, Xi secured an unprecedented third term as president, seeming to extinguish hopes of reform in the near future. It also seemed to validate a strategy favored by a new, post–Tiananmen generation of activists: to abandon the idea of a widespread uprising and focus on more realistic goals, like persuading western companies to cut ties with factories in areas where ethnic minorities are being persecuted.

Then, incredibly, Juntao’s prediction came true. In November, after ten residents of an apartment building in Ürümqi died in a fire, the Chinese internet lit up with accusations that Xi’s stringent “zero COVID” policies had made it hard for them to escape the blaze. Protesters filled streets across the country, from the industrial city of Zhengzhou to the elite Tsinghua University in Beijing. Some called for Xi to step down. It was fearless rhetoric of a kind nearly absent since Tiananmen and shocking to anyone who has watched China embrace growth over political liberty and seen it crush dissent.

The rallies belied everything the cynics and incrementalists thought they knew. Young protesters were waving signs and appearing maskless in front of police, risking their freedom and maybe their lives. Even more astonishing, the demonstrations seemed to work. Within ten days, the strongest authoritarian government in the world reversed course on one of its signature policies, abruptly easing lockdown restrictions.

Juntao’s platitudes about keeping the democratic flame alive during the darkest hours suddenly felt true. And while political analysts were careful to note the limited scope of the civil disobedience, a new generation had learned the lesson Juntao has spent his life trying to impart: that change is always possible. The next time we met, in late November, he was buoyant, calling the eruption a “turning point.”

He only wished Jim Li had lived to see it.

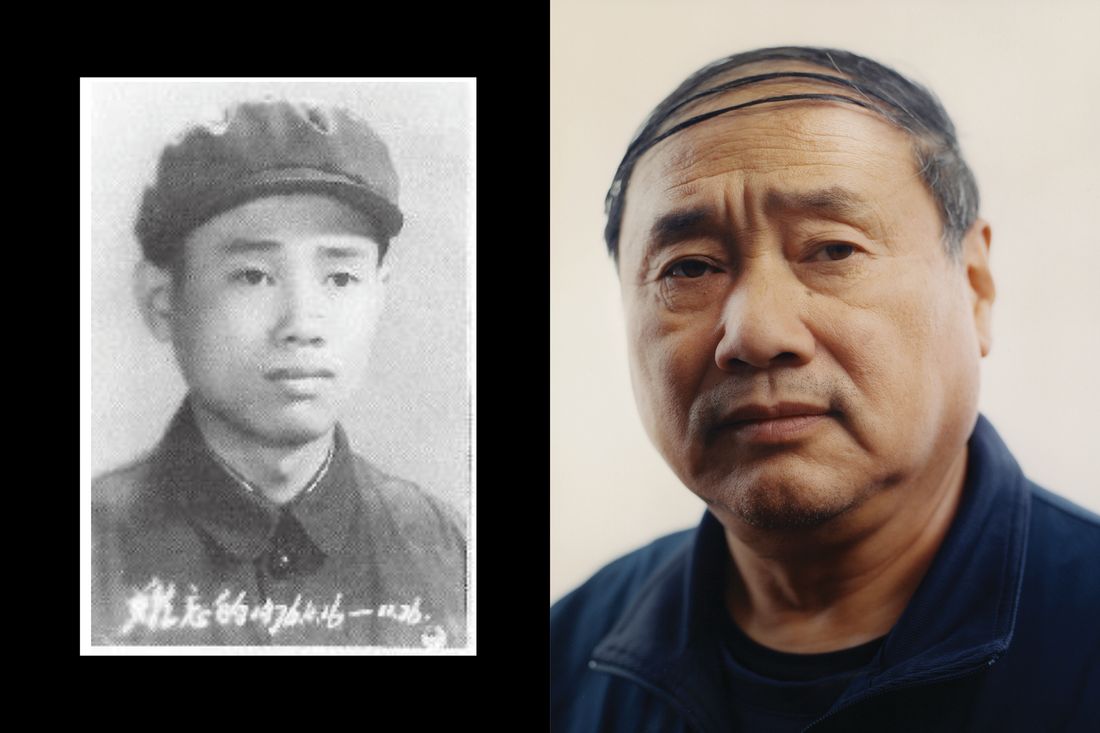

Juntao grew up privileged on the campus of a Beijing military academy where his father was a high-ranking official. His name means “billowing wave of the army,” and he imagined that one day he would be a great military figure. “I dreamed of leading the Chinese army to defeat West Point graduates,” he said. Juntao was 7 when the Cultural Revolution began in 1966, and he waved flags and sang songs as a dutiful Little Red Guard. But he also had a contrarian streak, devouring romantic wuxia epics in which wandering knights perform heroic deeds against daunting odds. In 1976, when a reported 1 million people filled Tiananmen Square to mourn the death of Zhou Enlai and criticize the so-called Gang of Four that had battled him for control of the government, Juntao led his high-school classmates in joining the demonstrations. Many of the protesters posted poems in the square, and the four Juntao put up are considered some of the most famous. One of them read, in part: “I swear to slaughter the traitors to fulfill the wishes of my elders / Armed with high spirits, I have no fear of knives or axes.”

His poems angered several members of the Communist elite, including Mao Zedong’s wife, and Juntao was jailed for 224 days — one for every word. He told me he was “proud” and “excited” to spend his senior year in prison, recognizing the value of notoriety. “I realized I would be very special,” he said. He saw it as an opportunity to learn about aspects of society that were closed off to most people, and the other inmates showed him that it was possible to live outside the system, independent from the party. “I learned a lot from those criminals,” he said.

It was a thrilling time to be a young democrat in China. After Deng Xiaoping began introducing market reforms in 1978, glimmers of liberal experimentation appeared: Villages began holding elections, and newspapers started investigating corruption. Peking University was the center of this political ferment, and after enrolling there to study nuclear physics, Juntao quickly established himself as a campus leader. By 1986, he had become a celebrity activist, and he took his organizing to Wuhan, where a friend introduced to Jim, who was then a law instructor.

Jim—who then went by his Chinese name, Jinjin — also came from a family loyal to the Communists. Before they took over in 1949, his father had been a tailor. By the time Jim was born, in 1955, he was a teacher at the police academy of Hubei province on his way to becoming a department head. For a time, it looked like Jim would follow in his father’s footsteps. He enlisted in the army at 15, serving as a telegraph operator, and later joined the Wuhan police department, assigned to catch pickpockets on city buses. But his politics changed at the Hubei College of Business and Finance, where he studied law and wrote a thesis on the U.S. Constitution. A professor who worked on China’s 1982 Constitution — which introduced reforms like term limits—showed him that changing the system was possible. Jim returned to Wuhan to teach. Upon meeting Juntao, he recognized a fellow idealist. They loved debating and drinking. Juntao was brash and provocative; Jim was serious and diligent, a scholar with a temper that could erupt unexpectedly.

Juntao and Jim soon moved to Beijing. Juntao helped start a think tank and staffed it with political scientists, economists, and statisticians — a bold new example of civil society existing independent of the Communist Party. Jim, who was lean and handsome with thick, expressive eyebrows, pursued a doctorate in law at Peking University, where he was elected president of the graduate-student body, a position that put him on the fast track to Party leadership. “If he had not joined the Tiananmen movement in 1989, his future would have been limitless,” a fellow activist told me.

In April 1989, after the death of Hu Yaobang, a liberal Party elder who had championed many of the country’s free-market reforms, students flooded into Tiananmen Square to demand wholesale change: accountability, due process, democracy. The protests lasted for weeks. As the crowds grew, Juntao, who was all but living at the square, began mediating between protesters and the government. He was a moderating force, ultimately trying to negotiate a deal in which the demonstrators would evacuate in return for the Party granting more independence to student publications, among other concessions. Meanwhile, Jim was working to organize a union called the Beijing Workers’ Autonomous Federation. Aside from a group that had briefly operated in Taiyuan years before, it was the first independent labor organization in the country. “Our old unions were welfare organizations,” Jim told a young New York Times reporter named Nicholas Kristof. “But now we will create a union that is not a welfare organization but one concerned with workers’ rights.” Jim’s alliance scared Beijing’s Party elite: That same month in Poland, a similar coalition had successfully negotiated for reforms with the Communist government.

On June 3, Jim got on his bike and headed toward Tiananmen for another night of protests. On the way, he heard gunshots and saw students running in the opposite direction, some injured and bloodied. The Chinese military had opened fire on protesters, killing hundreds. Jim turned back. A memoir he wrote in 2009 offers no further details.

Juntao tells his account of the atrocity sparingly too. “I’m sick of talking about the past before I get to the future,” he said. “I have to focus on what I’m doing now.” That night in Beijing, he was waiting to meet a friend at a hotel when word came of a shooting, and he asked his driver to take him to the scene. He saw wrecked cars and a protester who’d been shot dead. He spent the next few days trying to arrange escape routes for activists, then changed his clothes, permed his hair, and fled the city.

After the massacre, the Communist Party rounded up as many protesters as it could. Many escaped the country, but thousands were arrested and an unknown number were executed. Jim was caught after a few days and sent to prison in Beijing on charges of “counterrevolutionary propaganda and incitement.” In 1991, after 681 days behind bars, he was released when the government decided not to prosecute. He sold real estate and taught at small schools for two years, until the authorities allowed him to leave the country, along with his wife and son, and attend Columbia University.

Juntao spent four months after Tiananmen on the lam, working under a fake name at a factory in a small mountain town. After Juntao’s arrest, Premier Li Peng said at a Politburo meeting that he “must be shown no mercy.” Prosecutors accused him of being one of the “black hands” manipulating the Tiananmen protesters and charged him with “plotting to subvert the government.” A show trial resulted in a sentence of 13 years for him and a colleague, Chen Ziming — the longest of anyone involved. “It’s an absurdity,” a western diplomat told Kristof, who wrote about the case for the front page of the Times. “They needed somebody to blame for millions of people marching on the streets, and in public it’s come down to blaming these two guys.”

In prison, Juntao contracted hepatitis B that went untreated for months. He agitated for proper medical care, writing letters to top officials and staging repeated hunger strikes. The authorities put him in solitary confinement to prevent him from influencing fellow prisoners, but it didn’t work: The other inmates regarded him as a “king,” he told me. Even some guards treated him with respect, calling him “No. 2.” (Chairman Mao was No. 1.) Juntao sent holiday cards to his interrogators, writing, “I think of us as friends, not enemies.”

In 1994, after relentless petitioning by his then-wife, Hou Xiaotian, and international pressure on China to improve its human-rights record in exchange for trade privileges, Juntao was released from prison early to seek medical treatment in the U.S. He immediately took a flight to New York and was so excited to begin his new life that he didn’t sleep for 24 hours.

At Columbia, Jim found that the celebrity of his Tiananmen activism afforded him no great status. He and his family lived in an apartment near the university, and to make rent he delivered food for a Peking-duck restaurant. Later, they moved to the Midwest so Jim could get two degrees (a master’s of law and a doctorate) at the University of Wisconsin; eventually they settled in Queens, where they crammed into a one-bedroom apartment, sleeping on a borrowed mattress.

Juntao spent three years at Harvard, where he earned a master’s in public administration, then got another master’s and a Ph.D. in political science at Columbia. When he and Jim finally reunited in New York, then in their late 30s, they picked up their boozy bull sessions, conspiring to influence Chinese politics from afar. Hou described the pair as “like brothers.” They lobbied members of Congress to support fledgling pro-democracy groups in China and to pass resolutions promoting human rights there. A 1995 profile in the Washington Post described Juntao briefing a group of representatives, including Nancy Pelosi, in a small room at the Capitol and laying out a complicated strategy to use the expected death of Deng Xiaoping to unite reformers within and without the Communist Party and trigger a democratic reckoning.

In Flushing, Juntao and Jim organized events commemorating the anniversaries of the Tiananmen massacre and met with visiting Chinese dissidents. They teamed up to create advocacy groups, including the Chinese Constitutionalist Association and China Judicial Watch, and joined many more; Jim wrote the charter for the Federation for a Democratic China. But as one similar-sounding organization after another was founded, with similar personnel and similarly vague aims, China grew exponentially more powerful, navigating its way from global pariah to iPhone-making, Olympics-hosting juggernaut. The dissidents of the minyun had fiery rhetoric, but with Democratic and Republican administrations alike looking past human-rights issues to encourage investment, they were shouting in vain.

Juntao and Jim’s ambitions began to diverge. Juntao was an absolutist, always calling for total victory over the Communists. In 2010, he created a new branch of the Democratic Party of China — an organization that had started 12 years earlier in Hangzhou, had been promptly banned, and was then claimed by at least half a dozen splinter groups in Flushing alone. Juntao’s iteration grew to eclipse the others, with a shifting roster of a few hundred members. He began organizing weekly protests in New York and D.C., leading “study sessions” for members to learn about democracy, and offering news analysis on Chinese-language talk shows. His office became a clubhouse and de facto social-services center for new immigrants. He dispensed advice about where to live, how to find a job, and which lawyers were most dependable. “I’m their priest,” Juntao said. “I give them faith.”

Jim remained deeply opposed to the Communists. (Juntao recalls that Jim once saw an old couple dancing to a traditional Communist song in Chinatown and yelled, “Go back to China, fuck you!”) But his true calling had always been the law, not politics. He started a legal practice in Flushing on a shoestring budget and soon developed a reputation as a rigorous attorney specializing in immigration, asylum, and sensitive “Red Notice” cases protecting clients from being extradited to China. But he was a bad businessman, hiring friends and family and taking on too many cases for free. To attract more paying clients, Jim began attending social events hosted by a “hometown committee” — an organization friendly with the Communist Party. When his dissident allies objected, Jim told them, not very convincingly, that he was trying to influence the group’s politics from the inside.

Within a few years, he had saved enough to buy a house in Jericho, Long Island, and had taken up skiing and golf. When his parents immigrated, Jim bought a house for them, too, on a leafy street in Flushing. Jim’s father, bitter that his son’s activism had hurt his career, often warned him not to do anything “against China.” Jim would reply that he was working not against China but against the Communist Party. Either way, Jim grew more moderate as he got older. In 2006, he co-founded the Hu Yaobang & Zhao Ziyang Memorial Foundation, an organization dedicated to persuasion and reform, not revolution.

Jim also drifted to the right in U.S. politics. He voted for Donald Trump, largely because of his aggressive stance on China. On January 6, 2021, Jim posted on Twitter a video of the insurrection at the Capitol. He condemned the violence but objected to media descriptions of the crowd as a “mob.” “When students occupied the Square in 1989, the Communist Party said they were thugs,” he wrote in Chinese, adding, “Today we are not trying to overthrow the American Constitution, we are just expressing it.”

For younger Chinese activists, the Tiananmen generation is no longer the vanguard. In September, I went to Washington to visit Jewher Ilham, a prominent young advocate for Uyghur rights. On the fourth floor of a modern office building on K Street, Ilham, who is 28, explained how she helped persuade more than a dozen fashion brands to stop sourcing their products from Xinjiang province, where the government has reportedly operated forced-labor camps. “Some of them freaked out, like, ‘Oh my God, what should we do?’ ” she said. “Either for ethical reasons or because they’re smart enough to see there’s a global trend that’s coming.”

Ilham, who works at the Worker Rights Consortium, left for the U.S. in 2013 after her father, the economist Ilham Tohti, was detained by police at a Beijing airport. She has since campaigned for his release and the fair treatment of Uyghurs, whose suppression by the Chinese government the U.S. has called a “genocide.” When I mentioned the 1989 generation, she grew reticent. “I think we work separately,” she said diplomatically. “There’s a gap.” Some pro-democracy leaders have questioned aspects of the Uyghur-rights movement. Wei Jingsheng, who led the influential Democracy Wall movement in Beijing in 1978, has suggested, spuriously, that the Uyghurs have committed genocidal acts of their own; he has been accused by Uyghur activists of parroting Communist talking points about their history.

Other younger dissidents are concerned more with practical, day-to-day issues than with toppling the Party. At the McDonald’s on Flushing’s Main Street, I spoke with Yang Zhanqing, 44, a leader of the “rights defense” movement, which focuses on protecting Chinese citizens from land seizures, sex-based discrimination, and police abuse, using Chinese law to push back against the government. Yang and his cohort keep a purposely low profile. Whereas Juntao’s crew shouts in Times Square every weekend, Yang asked me not to mention details of his group’s recent activities, fearing retaliation.

The Trump era only widened the rift between the minyun’s old guard and the youth. Teng Biao, a human-rights activist and professor at the University of Chicago, says that many older dissidents support Trump because they adhere to a “conservative brand of western liberalism.” Having come of age under Mao-style socialism, when enemies of the regime were labeled “rightists,” they came to associate the right with virtue and to conflate progressive ideas with authoritarianism. Now, when Teng goes out to dinner with friends, he says, “we have to consider, ‘Oh, this person is a Trump supporter, this person is not.’ That’s a big harm to the dissident community.”

A young Chinese feminist activist I spoke with did not even want to be mentioned in the same article as the minyun. “We don’t see those people as our role models,” they said. The generations may share some experiences of being persecuted by the Communists, they explained, “but if they’re expecting us to learn from them — no.”

The activist also rolled their eyes at the old guard’s relative disinterest in progressive causes like racial justice. When I asked Juntao about Black Lives Matter, he said he supports the idea but is concerned about “security”: “If you tie the policeman’s hands, then criminals get their chance.” Countless American-born boomers have fallen out of ideological step with millennials and Gen Z; it’s that much harder for those speaking U.S. politics as a second language.

But the minyun needs fresh blood to survive. That is why, early last year, when a young woman arrived in Flushing eager to join the movement, Juntao and Jim gave her a warm welcome.

In January 2022, a 25-year-old named Zhang Xiaoning showed up at Jim’s office and asked for a meeting. She said that she’d been raped by a police officer in Beijing and that when she filed a complaint, the government covered it up and put her in a mental institution. Zhang got out and flew to the U.S. in August 2021. She’d been trying to bring attention to her ordeal, protesting in front of the U.N. and the White House. Now she needed a lawyer to help her apply for political asylum.

Jim was sympathetic but wary. Zhang seemed to have “emotional problems,” he wrote in a memo. But untreated mental-health issues are common in China, and while there were some discrepancies in Zhang’s story — in some paperwork, she complained of “sexual harassment” instead of rape — Jim trusted her. He agreed to take on Zhang’s case for free.

Over the coming weeks, they met several times to work on her asylum application, and Zhang acted more and more strangely, according to Jim’s memo. She asked whether Jim felt guilty about participating in the pro-democracy movement, given the “pain” it had caused his family. The memo goes on to describe Zhang emailing him complaining about other members of the minyun and calling them dogs; one evening, according to the memo, she phoned Jim nine times, then sent an email calling him a “loser.”

Zhang was living at a hostel on Kissena Boulevard in Flushing, sharing a room with several other women for around $450 a month, according to a fellow lodger named Victor. She had few possessions — a handful of plastic bags and a coat — and almost no money. She didn’t use her real name when interacting with roommates, instead calling herself “An-An.” Victor heard from the landlord that she was obsessed with Jim Li, showing pictures of the lawyer to her roommates and landlord and saying she was in love and wanted to marry him. (Jim’s first marriage ended in divorce, and he later remarried. I never saw any evidence that he was romantically involved with Zhang.)

On February 18, Zhang told Jim that the rape story was false. She’d heard of such things happening to other women, she said, but it hadn’t happened to her. Jim said he could no longer represent her. Zhang begged him to reconsider. Now that she’d publicly denounced the Communists, she would almost certainly be persecuted if she returned to China. In New York, she’d already been harassed by officials from the Chinese consulate, she said, and back home the Party had been giving her parents trouble. Having fabricated her case to boost her chances of winning asylum, she was now facing deportation — a worst-case scenario.

Zhang returned to Jim’s office repeatedly to try to change his mind. On March 11, she lost her temper and allegedly tried to strangle him. An employee called the police, but when they arrived, Jim asked them to let Zhang go. Later that day, Zhang called Juntao, almost crying, and asked for help. They’d spoken once before, and she knew that he and Jim were close. During an hour-and-a-half-long conversation, Juntao reassured her that she could make amends. All she had to do was bring Jim a dessert and apologize, he said, and the lawyer would come around.

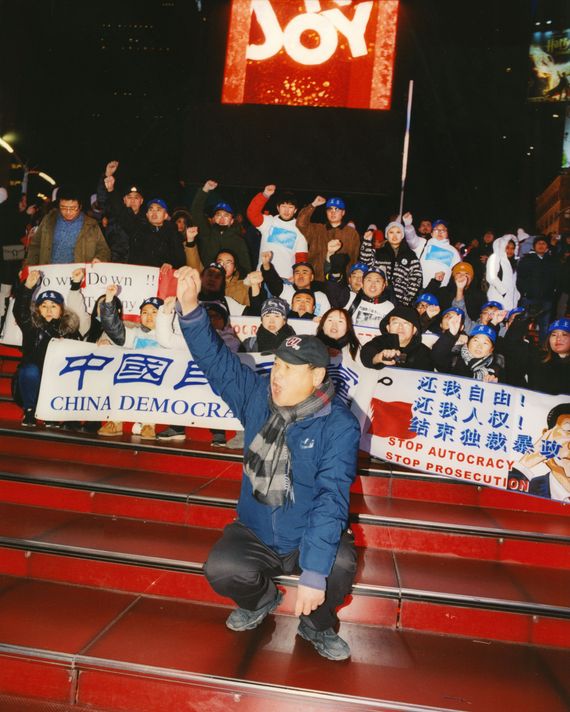

Juntao also suggested that Zhang join a protest he was planning for the next day. In Times Square, they met in person for the first time. Zhang was slight and nervous-looking, with rimless glasses. Wearing a blue face mask, she stood in front of a TKTS sign, raised a fist, and chanted, along with Juntao and a couple dozen others, “Free, free China! Democracy China!” At one point, Zhang removed her mask, exposing her face to the cameras. Juntao took it as a sign of her commitment and felt a surge of pride.

The following Monday, March 14, Juntao was driving when a friend called to say that Jim had been attacked. Juntao pulled into a parking lot and called Jim’s phone. No one answered, so he tried the office. Someone picked up and told him in a shaky voice that Jim was “gone.”

Zhang had shown up at Jim’s building that morning carrying a cake and saying she wanted to apologize — just as Juntao had suggested. Jim invited her into his office. A few minutes later, the secretary heard them arguing and then a shout. She opened the door to discover Jim in his swivel chair, covered in blood, with Zhang standing beside him holding a knife. Another employee charged in and restrained her while the secretary called 911.

Jim was pronounced dead at the hospital. The next day, Zhang was charged with his murder.

The days following the homicide were filled with bewildering developments. Before Zhang’s arraignment, a crowd of journalists and onlookers waited for her to exit the police station. As she passed the cameras, someone yelled, “Do you regret what you did?” Zhang shouted back, “You’re the ones who should feel regret!” As police wrestled her toward a waiting car, she called her critics “traitors” and accused them of “killing students.” Her meaning was obscure, but many assumed she was blaming the minyun for the deaths of Chinese citizens killed by soldiers in 1989.

On March 16, Juntao visited Jim’s office, taking in the large brown bloodstain on the carpet and laying flowers at a makeshift shrine. Jim’s employees told him they had found a strange clue: a couple of flags Zhang had left behind representing China and the Communist Party.

At almost the same moment, federal prosecutors in Washington held a press conference to announce the arrest of five men on charges of harassing and spying on Chinese dissidents in America. Juntao knew one of them well: Wang Shujun, a kindly historian who served as secretary-general of the foundation Jim had led. According to the Department of Justice, since 2005, Shujun had been collecting intelligence for China’s Ministry of State Security about dissidents in New York — which, if true, would almost certainly have included Jim.

Shujun’s arrest, combined with Zhang’s perp walk and the flags, fueled wild theories about Jim’s death. “When the FBI was about to close the net on Wang Shujun and the foundation, Li Jinjin was suddenly silenced,” one Twitter user wrote in Chinese, referring to Jim by his Chinese name. A local journalist wrote a song speculating about a connection: “They tell the press it’s just a coincidence / But denying the link to the murder makes no sense.”

When I met Juntao for dinner one night in April, he said he’d concluded that Jim was assassinated. “The dissident community has a consensus that this is political murder,” he said. Juntao said he believed the Party eliminated Jim because he was helping the U.S. government expose moles in the minyun.

The notion that Beijing ordered Jim’s killing is far-fetched. Nicholas Eftimiades, a former intelligence officer who studies Chinese espionage, said the odds of China sending an agent to assassinate an American citizen on U.S. soil are “pretty, pretty slight.” “If that was to become public, that would sink the relationship between the U.S. and China,” he said. “They’re not stupid.” When I presented this argument to Juntao, he took the classic conspiracist line: That’s what they want you to think. If Zhang didn’t behave like an assassin — attacking Jim after several people saw her enter his office with no evident plan for escape — that was just further proof of her professionalism.

As with any good activist, Juntao’s superpower has always been his ability to see what others don’t — to imagine the world as different from what it is. But that skill has a flip side. At one point, Juntao admitted that he can talk himself into believing what he wants to be true. “Sometimes people like me confuse subjective impression with objective reality,” he said. “If we believe something is true, it’s actually based on our hope, not on reality.”

The more theorizing I heard from Jim’s friends and colleagues, the more it started to sound like a form of grief. One reason his death hit the community so hard was that he didn’t live to see a democratic China. Jim’s peers were confronting the likelihood that they too wouldn’t see it in their lifetimes. They were mourning not just a friend, but also the cause.

After all they’d suffered, Jim’s death needed to have meaning. If it had been a state-sanctioned assassination, then he died for a reason. The hardest thing to accept would be that he had died at the hands of a disturbed maniac — in other words, for nothing.

Zhang, who pleaded not guilty, is detained at Rikers Island while her case progresses. She wrote me two letters, in perfect penmanship, declining to answer questions. But she did say she was disillusioned with the minyun. It’s not hard to understand how someone in her position would be frustrated: Groups like Juntao’s Democratic Party of China promise to help immigrants apply for asylum and trot them out in front of cameras to denounce the Communist Party. If their applications fail, they might well feel trapped and desperate, unable to live in the U.S. legally and unable to safely return to China.

Some of Juntao’s dissident peers have argued that this practice of boosting asylum applications in exchange for party dues and donations — Juntao calls them optional “thank-you gifts” — exploits immigrants and sullies the purity of the cause. Juntao bristles at this criticism, saying that even if new arrivals join his group for self-interested reasons, he can still persuade them to embrace democracy. He likewise rejects the argument that his entire project has failed because the Chinese Communist Party still rules. “People blame us, saying China is still under the CCP. I say, ‘Who do you think I am?’ I’m not a rainmaker. I’m not a god,” he told me once, in a rare flash of anger. “If someone says, ‘The CCP becomes stronger and stronger,’ I say, ‘Your fault is much bigger than mine. I did my best, but you did nothing.’”

If there’s no evidence that Zhang was a trained killer, the U.S. government’s case that Wang Shujun is a Chinese operative is richly documented. So is the fact that the People’s Republic cares deeply about the activist scene in New York and commits extensive resources to monitoring it. In 2020, the Justice Department charged a New York police officer with gathering intelligence on the city’s Tibetan community for the Chinese government. (Prosecutors recently moved to drop the case, citing new, unspecified “additional information.”) In October, federal authorities accused a father and daughter living in Queens and on Long Island of participating in “Operation Fox Hunt” — a covert Chinese campaign to harass dissidents and other Chinese nationals and coerce them into returning to the mainland. And this month, the Times reported that the FBI had raided a suspected Chinese “police outpost” at a building on East Broadway, one of more than 100 such offices around the world that surveil the Chinese diaspora.

Shujun was always more scholar than activist. After studying military history at one of China’s top academic institutions, he moved to New York in 1994. He published more than a half-dozen books of popular history, some of which sold well in Hong Kong and mainland China. In 2006, a dissident friend recommended him to serve as secretary general of the new Hu Zhao Foundation — of which Jim was also a founding member — and he accepted. According to the FBI, Shujun started collecting information about the activist community and passing it to Chinese officials. An indictment filed in May alleges that between 2005 and 2022, Shujun met with Ministry of State Security officers during trips to China, communicated with them on a messaging app, and shared information in the form of “diaries” he’d save to an email-drafts folder that Chinese agents could access. The indictment alleges that this amounts to conspiracy and failure to register as a foreign agent, among other crimes. (Shujun denies the charges and many details of the FBI’s account. His lawyer, Kevin Tung, said, “My client maintains his innocence and would like a judge to decide his case.”)

Some Flushing dissidents say they long suspected Shujun. “He didn’t speak honestly,” said one, Edmound Jiang, who thought Shujun treated him too much like a celebrity when he arrived in the United States. “It wasn’t natural. I’m just a regular person.” (Not long after we spoke, Jiang fell and died.) Juntao also doubted Shujun’s loyalty, partly because he traveled to China regularly and partly because he would ask about the nitty-gritty of minyun activities. “Nobody cares about the details except a spy,” Juntao said.

In 2012, Juntao shared his concerns with Jim. They were planning to hold a conference (“Deadlock, Breakthrough, and China’s Democratic Transformation”) with guests invited from around the world, including mainland China. Juntao was worried that the Chinese government would stop some of them from leaving the country, so he told Jim not to share the roster with Shujun. According to Juntao, Jim brushed him off. When the guests applied for permission to leave China, they were rejected. Juntao suspects Shujun alerted the authorities. (Shujun disputes this account, saying he did not see the guest list and that any rejections had nothing to do with him.)

On July 31, 2021, while Shujun was staying at his daughter’s house in Norwich, Connecticut, a young man knocked on the door. According to the DOJ’s version of events, when Shujun opened it, the man said he was sent by “the boss” to deliver a message. Shujun invited him in. The man said “headquarters” wanted to warn Shujun that the FBI had been monitoring him and offered to help him delete his “diaries” and other messages, according to the indictment. Shujun allegedly provided the young man with his passwords and told him to delete some of the diaries, but not so many that it would look suspicious. The young man — an undercover FBI agent — recorded the entire conversation.

Months elapsed, and Shujun was not arrested; then, two days after Jim was killed, he was. The Justice Department declined to answer my question about whether the two events were related.

On a sweltering morning in August, I went to Shujun’s apartment in Flushing, where he is free on bail. In his dimly lit living room, he turned on a fan, set down three cups on a table beside me — coffee, tea, and room-temperature Pepsi — and sat in a chair directly opposite me, our knees almost touching. At times, he leaned in so far that our faces were only a foot or two apart. He spoke energetically, with large gesticulations, which, along with his thick black hair, made him seem younger than his 74 years.

The DOJ’s case is all a big misunderstanding, Shujun told me. Sure, he’s met three of the four MSS officers mentioned in the indictment. And yes, he did have multiple lunches with one who was helping Shujun’s son-in-law in Hong Kong collect debts. But he never accepted money from them, he said, and the information he shared was all public. (On this last point, the DOJ disagrees.) Plus Shujun emphasized that it was his job to spread the news of pro-democracy activities. Jim had encouraged Shujun to tell Chinese officials about their work, he said. “If Li Jinjin were still alive, he’d be my biggest defender.”

To my surprise, Juntao defended Shujun. Even if Shujun was taking money from the Communist Party, it probably wasn’t for political reasons but rather as “a business,” Juntao said. “It’s the Chinese way,” he said. And anyway, Juntao said, he’d rather have an informant be someone he knows. That way, “I control what kind of information they get.” He said he still considers Shujun a friend who supports democracy. I found Juntao’s forbearance strange at first, but perhaps it makes sense for someone tired of losing friends.

Jim’s funeral in late March was an extravagant affair. Some 300 mourners gathered at the Chun Fook Funeral Home in Flushing, spilling out of the main room into the lobby, and countless wreaths and hand-painted poetry banners decorated the walls.

Juntao hung off to the side with a huddle of activists, grousing. Jim’s family wanted the ceremony to be strictly apolitical; in some ways, it even favored the Communist Party. The music was a dirge typically played at the funerals of Party leaders, and at one point, a guest carrying a sign with the famous Tiananmen “tank man” photo was escorted out. A signed obituary circulated, listing Jim’s legal colleagues above the pro-democracy crew.

Some members of the minyun thought the sanitized occasion was an insult to everything Jim had believed. He might have lost some of his revolutionary zeal as he adapted to a life of homeownership and golf, but he still loathed the Communists. When Juntao went up to speak, he ignored the no-politics rule and gave a rousing eulogy praising Jim’s quest for freedom and justice, invoking the memories of fellow dissidents and imagining a day when they could hold a public funeral for all of them back in China.

Later, Juntao and his minyun colleagues held a second, explicitly political memorial. In an upstairs ballroom at a mall down the street from his office, they told stories about Jim’s activism in Wuhan and Beijing and how he’d kept up the fight in the United States.

Absent from either ceremony was Jim’s elderly mother, who lived just a mile away. After some discussion, Jim’s friends and family had decided not to tell her that her son was dead. Instead, they told her he had gone abroad.

All summer and fall, week after week, Juntao held his usual rallies in Washington and New York, unfurling the same banners and chanting the same slogans. After the breakthrough COVID protests swept across China in November, we met in his office one last time. I asked if the burst of public dissent vindicated his long-term approach to change. Juntao replied that every generation has to come by its democratic awakening organically, often after some experience of repression. “Some ideas passed from us to them,” he said. “But they may not even know.”

More on China

- The Secret Weakness of TikTok’s All-Powerful Algorithm

- Why Your TikTok App Will Probably Be Taken Away

- Big Tech Still Has a Big Addiction to China