When people asked me what it was like inside the courthouse where Donald Trump stood trial, I said it reminded me of covering a political convention. It was a programmed event, with tentpole speakers, like the star witness, Michael Cohen. There was a nominee, chosen by indictment, who swept in each day with a swarm of loyal surrogates. There was press pack, wearing credentials on their lanyards, all writing down the same words, and breathing the same stale air. After final arguments, though, the atmosphere shifted. As the case went to the voters of the jury, it felt more like Election Day, when there’s nothing left to do but wait. The reporters hung around the 15th floor of the Manhattan criminal-court building, trading theories and gossip, trying out takes.

The jury of 12 New Yorkers — seven men, five women — seemed to be in no hurry. At the end of their first day of deliberations, May 29, they passed a couple of notes to Judge Juan Merchan, asking for a read-back of some testimony and, more significantly, his jury instructions. The next morning, Thursday, they all filed back into the courtroom and Merchan once again gave his explanation of the law. You couldn’t blame the jurors for wanting to hear it a second time.

The Manhattan district attorney, Alvin Bragg, had advanced a complex theory of the case, in which one intended crime (a conspiracy to win election via illegal means) was accomplished through a second intended crime (the jury could take its pick from several options, including the violation of federal campaign-finance laws), and concealed through a third crime. The charges Trump faced, 34 counts of falsifying business records, related only to the coverup. The triple bank shot elevated the business-records charge, normally a misdemeanor, into a felony. But it also served a larger justification for the prosecutors, who had been criticized for singling Trump out for a minor offense. It allowed them to say that the case was about something more nefarious than having a sexual encounter with a porn star, or paying hush money through a lawyer, or conspiring with the chief executive of the National Enquirer to keep a candidate’s secrets.

In his summation, prosecutor Joshua Steinglass told the jurors they should analyze the evidence through “the prism” of “three rich and powerful men, high up in Trump Tower, trying to become even more powerful by controlling the flow of information that might reach the voters.” In other words, he was saying, the underlying crime was the denial of knowledge.

Going into the trial, many legal commentators — even ones who otherwise hated Trump — questioned whether Bragg’s theory would hold up. But Merchan had largely accepted it, and his instructions were written in a way that seemed to point in one direction. As Merchan read them to the jury again, Trump sat with his eyes closed. But he belatedly woke up to the fact that the boring stuff was worth his attention. In the afternoon, from the courthouse holding room that he used as his command center, he posted to Truth Social that the instructions were “UNFAIR, MISLEADING, INACCURATE AND UNCONSTITUTIONAL.” His lawyers had promised to appeal any guilty verdict, and they stood a decent chance on the merits. But for now, Merchan’s word was law.

Trump has spent this unusual election year treating his court dates as an extension of his campaign. During the primary season, he spent much of his time at two civil trials, one for corporate fraud and the other for defamation. In each case he has adopted his familiar political strategy, picking out his opponents — judges, prosecutors, even a court clerk — and savaging them on social media. Before the criminal trial began, he attacked Merchan as a biased hack, calling attention to the judge’s (tiny) political donations to liberal causes and the fact that his daughter is a Democratic political consultant. When a gag order, and the threat of being jailed for contempt, finally forced Trump to lay off, he called in reinforcements. “It is a political persecution, it is a witch hunt,” Donald Trump Jr. told the TV cameras outside the courthouse after watching closing arguments. He then singled out a member of the prosecution team who previously served as an acting associate attorney general. “There is a reason one of the people sitting at that desk was the number-three person in Joe Biden’s DOJ. I know my father is not allowed to say ‘Matthew Colangelo,’ because he’s been gagged. The president of the United States is not allowed to exercise his First Amendment rights in New York City, in this day and age.”

Trump has discovered, however, that the demean-and-destroy strategy that works so well for him as a candidate is less effective within the legal system. Merchan is silver-haired and generally soft-spoken, but his demeanor belied a determination to bring Trump to trial, kicking and screaming. While Trump’s legal team successfully managed to tie up his federal cases with appeals and procedural motions, Merchan kept the New York State case running on a tight schedule. He denied the defense’s attempts to significantly delay the trial over evidentiary issues. He kept juror selection moving along quickly, and the jurors turned out to be diligent and committed. He held Trump in line. On the second day of jury selection, he noticed the defendant was audibly complaining. “I will not tolerate that,” Merchan told him. “I will not have any jurors intimidated in my courtroom. I want to make that crystal clear.” After that, Trump hardly uttered a peep.

Six weeks after the trial began, the case went to the jury. At around 4 p.m. on Thursday afternoon, the prosecution and defense lawyers, as well as Trump, reentered the courtroom, where the reporters in the gallery were lazily passing the afternoon. Merchan came in and gave them a routine update: He would be telling the jury to go home for the day as scheduled, at 4:30. “We’ll give them a few more minutes,” he said, before disappearing out the side door. The judge was gone for a little while, and then he returned, with an odd look on his face.

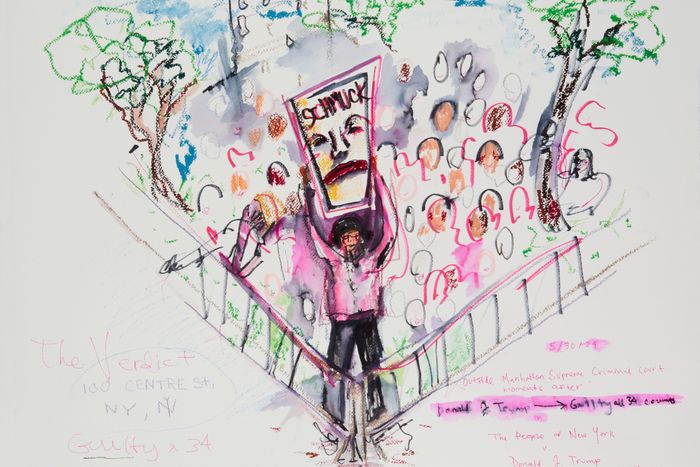

“I apologize for the delay,” Merchan said. “We received a note. It was signed by the jury foreperson at 4:20. It’s marked as Court Exhibit Number 7. It reads: ‘We, the jury, have a verdict.’” From the gallery, there was an audible gasp, and the clatter of laptops. “Please,” the judge said, “let there be no outbursts, no reactions of any kind once we take a verdict.”

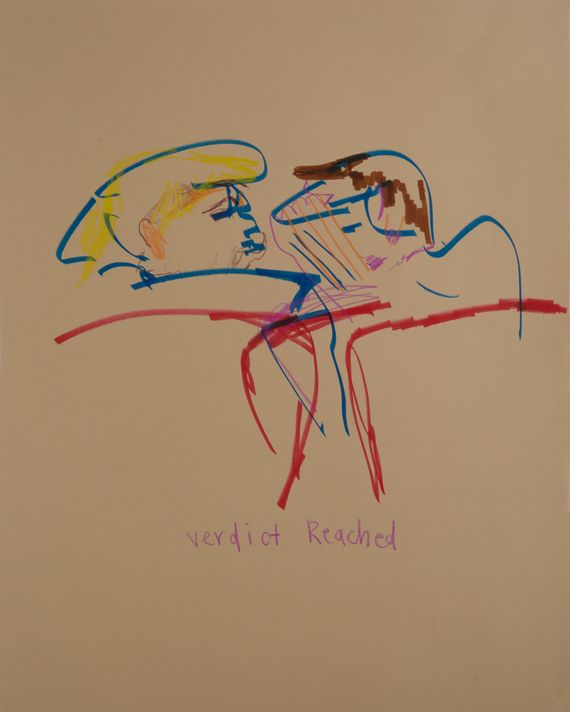

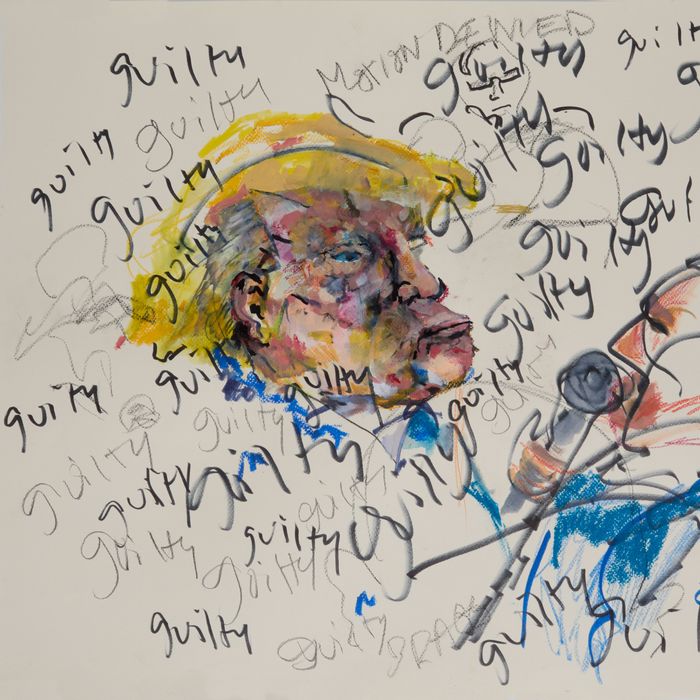

Eric Trump, the sole member of the defendant’s family present, stalked out of the courtroom, wearing a stricken expression, and returned a few minutes later. His father sat at the defense table, his arms crossed over his bright blue tie, and then leaned in as his attorney, Todd Blanche, whispered to him behind his hand. He turned up his chin and prepared to take the punch. He stood as the jurors filed into the hushed room without giving him a look. And then the foreman, an Irish immigrant, pronounced him guilty, 34 times over.

Blanche asked, as a formality, for the jurors to be polled. Trump turned to look at them one more time as each was asked if they agreed with the verdict, and each answered: “Yes.”

Otherwise, Trump showed no visible reaction. The man who never admits defeat or accepts punishment had suddenly been rendered helpless before the law. He is scheduled to be sentenced on July 11, four days before his party convenes for its actual political convention in Milwaukee. On his way out of the courtroom, Trump gave a dispirited, jerky handshake to his son, and then walked out to the press pen to deliver a statement. “This was a rigged, disgraceful trial,” he said. “The real verdict is going to be November 5 by the people.” If that one goes his way, Trump will return to power, and he will be able to put off any state-court sentence. He will also be able to order the Department of Justice to dismiss his federal cases. Then, if past is prologue, he will turn to payback, and will seek to lock up his own perceived enemies.

Even if he never serves a day in jail, though, the felony conviction assures at least one outcome. This time around, there won’t be any conspiracy to hide the truth about the Republican Party’s candidate for president. And the American voters will know exactly what they are getting if they elect him president. Donald Trump is a criminal.

More on Trump on trial

- Why Michael Cohen Still Misses Donald Trump

- What It Was Like to Sketch the Trump Trial

- What the Polls Are Saying After Trump’s Conviction