Take a look at pictures of Jerome Powell, the chair of the Federal Reserve, and you rarely see a man enjoying himself (although he has been known to blow off some steam at Dead & Co. concerts). Since the start of this inflationary era, his public persona has mostly toggled between Very Serious and No Really, Very Serious. And for good reason. His job can be boiled down to making sure the $25.4 trillion U.S. economy — upon which much of the global financial system relies — is basically working right. That involves considering everything from the unemployment rate to the price of canned soup to deciding, for instance, whether interest rates should be higher or not. Not easy.

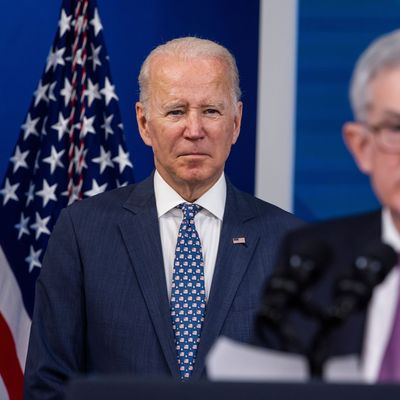

What makes it all the more challenging is that there are a lot of people who have opinions about how he should be doing his job. Some of those people merely have X accounts, but, occasionally, some of those people are U.S. presidents. Donald Trump, while he was in office, called the Fed board “boneheads” for not lowering interest rates to his liking. That was generally frowned upon, since it was seen as meddling in something he ought to leave up to the Fed. But Powell has also seen a gentler, more polite version of that same nudging from Joe Biden, who predicted last month that we’ll see “those rates come down more” by the end of the year. It was a not-so-subtle way to pressure the otherwise independent central bank to do the thing that financial markets were expecting and cut rates around three times this year. But over the last week, at least six Fed officials — Powell’s colleagues on the Fed committee that sets rates — signaled that those cuts may not come anytime soon, and interest rates could actually go higher. This has taken on a more urgent valence with an election just a bit over six months away. While lower rates probably wouldn’t be the reason Biden would win in November, the opposite certainly could hurt his chances. What is going on?

The Fed’s benchmark rate, which is now higher than it’s been since 2001, is, in one sense, just a number: 5.33 percent. But it is also one of those invisible economic forces that reveals its full power indirectly. Interest functions like a tax with less economic benefit, a way to siphon money away from people without getting some public service in return. Higher rates typically translate into rising levels of unemployment, less investing, fewer home purchases, and less shopping — in short, a form of austerity. But the Fed raises rates for a reason — that is, to lower the rate of inflation.

For the past three years, the Fed has been in rate-hiking mode. This is, generally, not the mode that presidents like to find the economy in when they are running for reelection. But in late 2023, something started to change. Inflation cooled and Wall Street saw good times ahead. After Fed officials penciled in three rate cuts for the year, the financial industry went even further and predicted the central bank would actually cut five times. The idea here was that the economy was sturdy, but that lower rates would be needed — perhaps as early as March — to keep it from tipping into a recession.

With April half over, that clearly hasn’t happened. Last month, inflation unexpectedly rose. Biden — for reasons unknown — thought it would be prudent to comment on the Fed’s path to cut rates. “This may delay it a month or so, I’m not sure of that. We don’t know what the Fed is going to do for certain,” Biden said on April 10. But a one-month delay now seems quaint. The Fed reported on April 17 that the economy is still expanding. This “did little to assuage market concerns regarding the Fed’s more hardened ‘higher for longer’ narrative,” Quincy Krosby, chief global strategist for LPL Financial, said in a note.

According to Gallup polling, most people think the economy is fair to poor, and it’s only going to get worse. In a sense, this seems untethered from reality: The unemployment rate is still under 4 percent; inflation, while above the 2 percent target, is much lower than it has been; and wages are outpacing inflation. But the fact that prices are still rising, often in unexpected places, continues to surprise people. For most Americans, staying solvent isn’t just a matter of finding a new place to buy groceries — the rising costs of insurance and rent are major factors in the stubbornly high inflation rate. And if you want to buy a house, mortgage rates are now back up above 7 percent, the highest they’ve been in a year.

The reality is that if you’re worried about inflation corroding your spending power, it wouldn’t matter who is in the White House. But the equation doesn’t work the other way around — if you’re worried about being in the White House, inflation eating away at people’s bank accounts is really important. It’s not a good position to be in. If Biden jawbones the Fed for more cuts and it doesn’t work — or, worse, it does work and inflation spikes — then he looks weak or destructive. But as far as Biden is concerned, the outcome might not be much better if the Fed holds steady.