After Donald Trump’s surprising win in 2016, reporters frantically rushed to diners in the Rust Belt to find the white working-class voters who backed him after previously supporting Democrats. In the Midwest, counties all along the Mississippi River flipped from Barack Obama to Trump. On the Iowa side, this shift transformed the state from a perennial toss-up to a relatively safe Republican bastion. Over in Wisconsin, though, the transformation was less stark, and today this cluster of voters is one of the last redoubts nationally for Democrats among white voters without a college education. It might be the swing-est part of what has been the most fiercely contested swing state in the country in the past decade.

Nearly every race in Wisconsin is close and consequently brutal. In the Senate, it is represented by diametric opposites: Democrat Tammy Baldwin, a progressive who was the first open lesbian ever elected to Congress, and Republican Ron Johnson, a right-wing Trump acolyte and longtime vaccine skeptic. After voting twice for Obama, the state went for Trump, then Joe Biden.

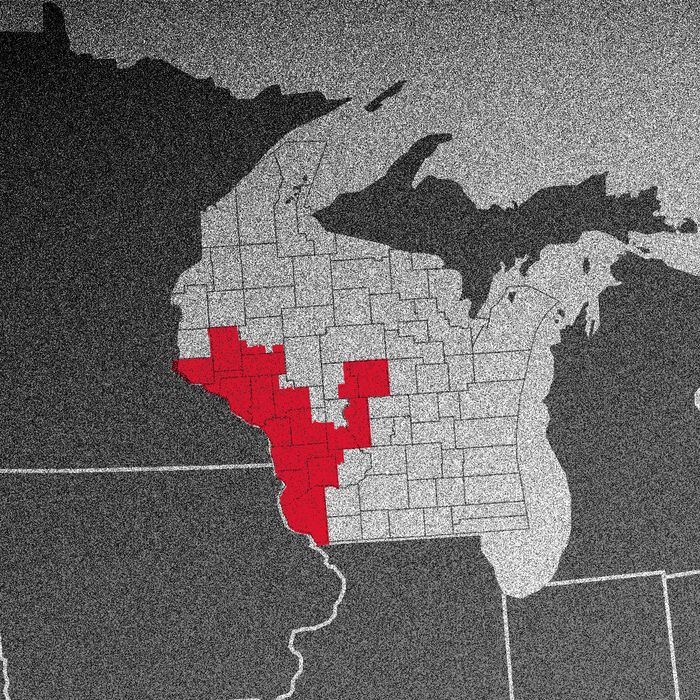

The winner in 2024 may be determined in the third congressional district in the southwest part of the state, which stretches along the eastern banks of the Mississippi. It includes both factory towns and family farms snuggled into steep valleys, as well as four different campuses of the University of Wisconsin. Closer to Minnesota than Lake Michigan, part of the district is even in the Minneapolis media market. (A Wisconsin political operative pointed out that one of Baldwin’s most astute moves in the district was to introduce legislation forcing Minneapolis television stations to carry Packers games.) Baldwin carried the district in 2018, while Johnson held it four years later. At the presidential level, both Trump and Obama won the district twice. “Voters in the district might decide the whole federal trifecta” of the White House, the Senate, and the House, as Ben Wikler, the chair of the state’s Democratic Party, put it.

Both presidential campaigns are campaigning heavily in the district, seeing it as key to securing Wisconsin’s ten electoral votes and the western flank of the Democratic “blue wall.” Trump has appeared twice in the district in the last few months and both Kamala Harris and Biden have dropped in. Tim Walz, who represented a demographically similar congressional district just across the state line in Minnesota, has visited often. For Republicans, the district is especially crucial as they need to not only maximize their rural vote in the state but win over as many blue-collar Democrats as they can. Democrats, meanwhile, need to hold serve with these voters, if not win some back, while turning out their base in Madison and Milwaukee and continuing to make progress in once-Republican suburbs.

Both times that Trump won the district, its longtime Democratic incumbent congressman Ron Kind won reelection too. After Kind declined to seek reelection, Republican Derrick Van Orden, a brash ex–Navy SEAL, won the open seat. He ran barely a year after attending Trump’s “stop the steal” January 6 rally in front of the White House and courted controversy by yelling at House pages while giving a tour of the Capitol. Van Orden has also been an ardent ally of House leadership and a vocal critic of the far-right insurgents who ousted then–Speaker Kevin McCarthy last year.

Van Orden is considered the slight favorite against Rebecca Cooke, a Democrat trying to help her party win back the House, especially with Trump at the top of the ticket. (Democrats recently hyped an internal poll that shows Cooke up by one point.) No matter what, the race will be close. As Brandon Scholz, a Republican consultant in the state, put it, getting 52 percent in the district would be doing well.

Cooke is running as a centrist Democrat, emphasizing her background growing up on a family farm and working as a waitress three nights a week while campaigning for Congress. “I think people are looking for folks that they can relate to, folks that they know are going to actually work for them in Congress and not just be another rubber stamp for their party,” she says, adding that there is a need for “more working-class voices in Congress, people that aren’t so far left or so far right, but want to work across the aisle and actually get shit done.”

That means persuading Trump voters to split their tickets for her. “I go up and I shake their hand,” Cooke says. “I say, ‘See who you’re voting for at the top of the ticket, but I need you to break for me.’” Her campaign isn’t just trying to appeal to MAGA, though. Like Democrats across the country, she’s also emphasized abortion, which is still a live issue in Wisconsin, where a 1849 law banning abortion under any circumstances remains on the books. In one campaign ad, she emphasizes that she wants to secure the border while also accusing Van Orden of supporting a national abortion ban.

The most recent polls show Harris and Trump are virtually tied, and Baldwin has the narrowest possible lead over Eric Hovde, a wealthy businessman. Says one operative, “Wisconsin has Wisconsined.”