|

![]()

|

|

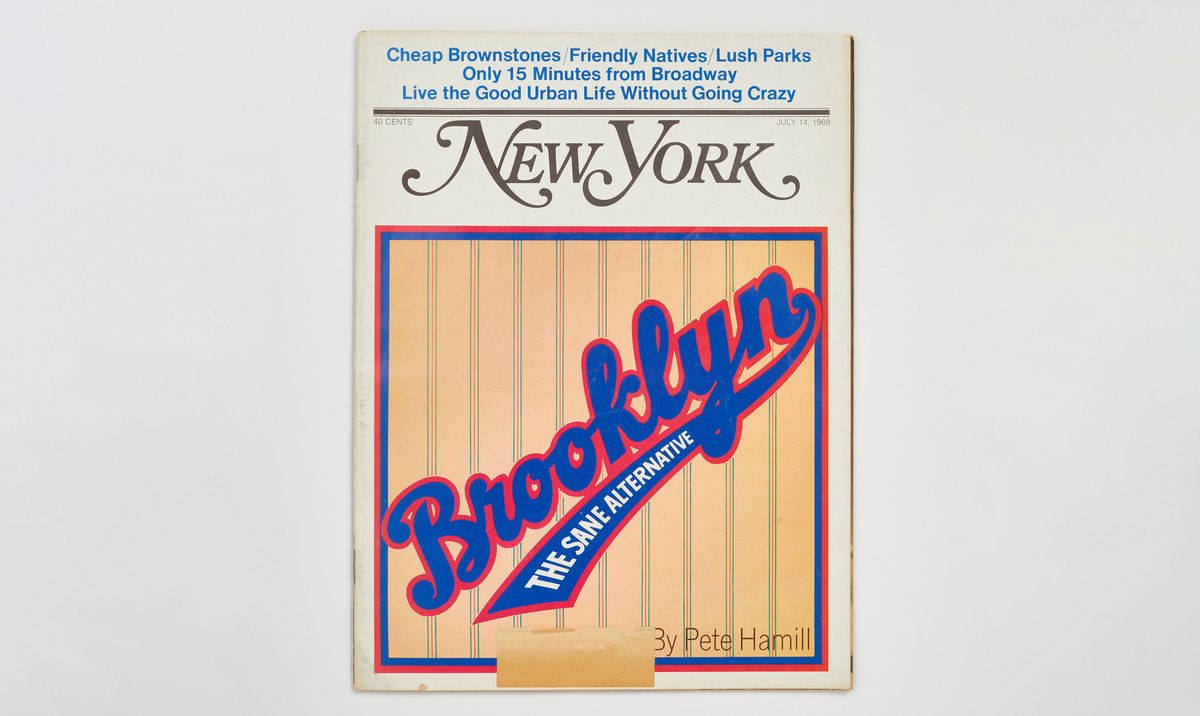

Photo: New York Magazine

|

| |

Almost from our inaugural issue, New York Magazine’s editors grasped that our readers were dying to peer into real estate — either other people’s or, potentially, their own future homes. One of our earliest cover stories was headlined “What Does It Take to Get a Decent Apartment in the Year of the Great Apartment Squeeze?” Another, from 1970, was a hate-read (before we had that term) about a family paying $50 per month for a generously sized midtown apartment. If house-hunting in this city is indeed a full-contact sport, New York has, for more than five decades, been its ESPN. In 2020, we made that commitment even more explicit, acquiring the real-estate site Curbed and bringing it back to its original focus on New York City’s built environment. Now, for this new season of the Reread newsletter, we’ll be revisiting ten New York stories that delve into this obsession.

|

|

Today, Brooklyn is a magnet, a place people all over the world aspire to live. In 1969, it was, for many New Yorkers, a place you left if you could. White flight to the suburbs, job flight to the South and the West, and decades of redlining had kept property values down and fostered decay. It was growing dangerous to live here: The citywide homicide rate doubled between 1967 and 1971, and heroin use and gang violence were increasingly entrenched. A good portion of the housing stock was made up of brownstone rowhouses, and they were considered undesirable: too narrow, too many stairs, too dark and Victorian-gloomy, nothing like the split-level ranches of Massapeqeua. A lot of them, during the Depression and afterward, had been broken up into rooming houses. Some had been abandoned by their owners, who gave up on paying the taxes and walked away, though Park Slope had comparatively few of those.

|

|

Pete Hamill had grown up on Seventh Avenue in Park Slope in the 1940s, in a fourth-floor walkup heated by a kerosene stove. The neighborhood, then, was largely Irish, Jewish, and Italian — like Brooklyn as a whole, which was 95 percent white in 1940 — and was full of families supported by blue-collar work at the Navy Yard. By the time Hamill moved back to the Slope in 1969, as his first marriage broke up, it was more diverse, with Black and brown residents among the white ethnics. (Their coexistence was not entirely harmonious; there had been fights over race and class, both in the courts and on the streets.) What Hamill saw, however, astonished him. Young professional-class families were buying the old run-down brownstone houses and spiffing them up. Some were meticulously restored to single-family use, others reimagined in various modern architectural idioms, still others reworked into a few apartments. And why not, he posited? They were as close to downtown-Manhattan jobs as the Upper East Side was. They were overbuilt and sturdy, constructed in the pre-Sheetrock age. A lot had the elaborate architectural gingerbread that had gone way out of fashion but was, in the 1960s, coming back again. Just as quite a few hippies chose to go back to the land, chopping wood and cooking whole grains in an old farmhouse somewhere, young urbanites were doing something a little similar near the IRT. (A few of them started the Park Slope Food Co-op shortly thereafter, in 1973.) Most of all, the brownstones were cheap.

|

|

How cheap? Oh, God, you really don’t want to hear it — except of course you do. You could get a very nice Park Slope brownstone for $30,000 (somewhere around $240,000 in today’s dollars), and a livable one for $20,000. (Less, if it needed a lot of work.) That was approximately the cost of a three-bedroom house in a commuter suburb in New Jersey, or in northeast Queens, or much of Nassau County. It was perhaps half what a similar house cost on the Upper East Side. You sometimes had to have cash, because the banks wouldn’t write you a mortgage. But by way of comparison: A professional-class starting salary in 1969 was about $9,000. If they lived frugally, a moderately successful two-income couple — a lawyer and a teacher, say, or a pair of advertising copywriters — could save up enough in a few years to buy a whole building. Unthinkable now.

|

|

Hamill described the allure of the neighborhood this way: “Hundreds of people are discovering,” he wrote, “a part of New York where you can live a decent urban life without going broke, where you can educate your children without having the income of an Onassis, a place where it is still possible to see the sky, and all of it only 15 minutes from Wall Street. The Sane Alternative is Brooklyn.” On and on it went, with astonishing prescience. We almost could have updated the prices and run a version of this story — barely changing it, apart from excising the references to the recently departed Brooklyn Dodgers — again in 1979 or 1989 or even 1999. Only in the new century did moving to Brooklyn cease to be much of an alternative for the well-off; the prices in a lot of neighborhoods had risen to match and even exceed those in Manhattan.

|

|

Moral questions began to come to the fore as well. “Gentrification,” to use a word that did not even appear in the Times until several years thereafter, was back then considered a benign force at worst, a matter of money and services flowing back into neighborhoods that had been decaying. It was hard to argue against it in, say, Soho, which had been a derelict industrial neighborhood with few residents and a lot of empty space for artists. The new people arriving in Park Slope were a trickle, not a flood. But as New York became richer, that flow of people and money increasingly began to push into neighborhoods that had complex social structures of their own and sweep those residents out to sea. Over and over, areas that were poor or working-class and majority Black became much more affluent and much whiter. Every possible reading, both good and bad, of these socioeconomic shifts has been offered: Some longtime residents say that the new money brings with it better services that they appreciate, and owners who cash out can draw a tremendous windfall. But long-term tenants trying to hang on in a quickly gentrifying neighborhood are, far too often, screwed. Even if they’re the lucky ones who are protected by rent stabilization, when (for example) the neighborhood bodega with $3 sandwiches becomes an upscale shop charging $14, they’re going to have a hard time. Some of that change may be inevitable in a desirable city with an increasing population, but when it happens at high speed, the collateral damage is significant, and it usually hits the most vulnerable people hardest.

|

|

But all of that lay in the future. The first wave, at least, was more a subject of wonder than anything else. Here’s “Brooklyn: The Sane Alternative.” Read it and weep — for the house that, unless you were very lucky, your parents or grandparents did not buy in 1969.

|

|

|

— Christopher Bonanos, city editor, New York

|

|

Revisit more classic stories from the archives. Subscribe now for unlimited access to everything New York.

|

|

![]()

|

|

Photo: New York Magazine

|

| |

|

|

|

|