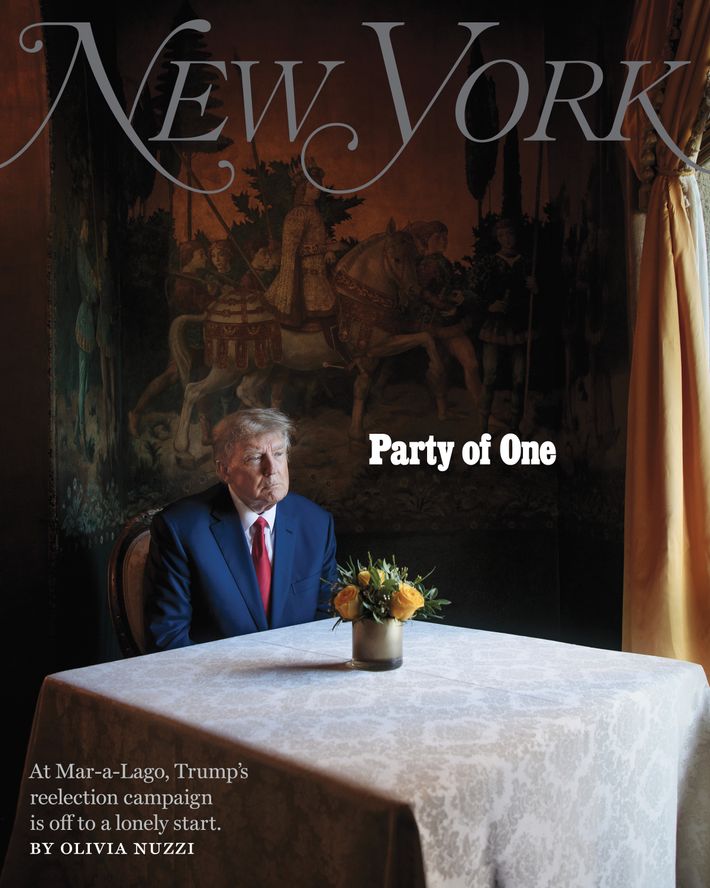

New York Magazine’s January 2–January 15 cover story is a feature by Washington correspondent Olivia Nuzzi on Donald Trump’s quiet and lonely run for reelection and includes interviews with Trump as well as some of his closest aides. Owing to the holidays, the story has been published online prior to the magazine’s January 2 release and is available today. Below is background from Olivia Nuzzi on her profile.

In 1980, New York Magazine published one of the first meaningful profiles of Donald Trump, by Marie Brenner. “The first time anyone heard much about Donald Trump was about five years ago. And it all sounded very fishy,” she wrote. It is an astonishing document, an account of a psychologically weird real-estate developer with a dream of building “the monumental structures.”

He would go on, of course, to stomp around a razed America. But before all that, he was a hyperactive and “pushy kid nobody took seriously” with an “edifice complex” and “Third Avenue glitz,” in Brenner’s words. His brother, Robert, told her how Donald would steal his bricks when they were growing up, “and then he would build a tall building, and then he would glue all my bricks together, and that would be the end of my bricks.” His father, Fred, told her, “I tried to bring Donald down to earth many times,” but he couldn’t shake him of his desire for “quality” and for a bigger life, a life outside Jamaica Estates.

By the time Brenner was accompanying him around Manhattan, Trump had been “legitimized” by the success of his early real-estate projects, and although he exaggerated the height of his skyscrapers — “He lies,” Brenner wrote — and people thought he might be “a megalomaniac,” he was “bringing in millions of dollars in construction to the city (and making millions for himself)” and “having a very, very good time” on his rise to power. Happiness for him, Brenner wrote, was “the monomania that comes when you know exactly what you want.”

So Trump was Trump, then as now, but with a few jarring differences. A Trump Organization executive, Barbara Res, once told me of how she watched in mounting despair as he got more and more famous and lost his sense of self-awareness. Brenner captures Trump at a time when he is still tethered near, if not quite to, the common human experience. “Real estate has to be show business,” he told her. “Only the rich can afford to buy. I’ve had to make my deals with a certain amount of flash. I want materials that glitter, that sparkle, the best of everything, you understand. That’s part of the sell. I always go to these meetings, and I’m always the one who gets all the attention. It’s always, ‘Mr. Trump, Mr. Trump, Mr. Trump’; maybe you shouldn’t write that out of my mouth — it’s a little embarrassing.”

Ten years later, in 1990, Brenner profiled Trump again for a different magazine, drawing on her decade of insights to paint a full portrait of his psychology in a period of failure and isolation, his businesses collapsed, creditors hounding him, and his marriage on the rocks. In the account of this moment, After the Gold Rush (Vanity Fair), he is a victim of his appetites, bleeding from his wounds but still insatiable.

Brenner so completely had Trump’s number that nothing else ever really needed to be written. Or there wouldn’t have been any need, had he not ended up in the White House.

In concept and style, Party of One is in many ways my tribute to Brenner. It is a story that begins, for me, eight years ago, at the bar of JG Melon, where I first stepped inside Trump’s orbit as a 21-year-old with no idea what I was getting into. It was around this time that I met Brenner, though I also had no idea how vital her work would become as I tried to find my way through the 2016 presidential campaign, the four years of the Trump administration, the 2020 presidential campaign, and now this, the strange after.

“All reporting is a form of outrage,” Brenner told me. Trump responded to Brenner’s reporting with his own, once pouring a glass of wine down her dress at a society function and, at another moment, going on a tirade during a Barbara Walters interview. Such is his relationship with the truth. “It’s a weird badge of honor that I never wanted,” Brenner said.

“He has unleashed forces of hatred in this country that will take decades to get over, if ever.” For much of the last three years, Brenner has been embedded at New York Presbyterian, reporting on the pandemic. Her book, The Desperate Hours, was released in June. “The anti-science jihad that came out of the Trump White House is responsible for hundreds of thousands of needless deaths in this country,” she said. “Historians will one day grapple with how and why,” but they will not need to ask who.

Brenner long ago moved on from Trump as a subject. Still, you can’t just forget some of these things. “There’s a moment that stays with me from the After the Gold Rush reporting,” Brenner said, “when I heard that he had burrowed into Trump Tower, and was just stuffing himself with hamburgers and french fries, and I imagine that’s his default position, the child in him.”

My account of the first month of Trump’s 2024 presidential campaign was reported from inside Mar-a-Lago, based on interviews with more than 20 sources — including Trump himself — from the campaigns and the family, from the White House, and hanging now on the periphery. It is a familiar tale of Trump in isolation, having gained and lost the world, only now the stakes have changed.