The city is many cities, that’s the beautiful thing. Everyone builds their own New York, mostly out of the people who surround them. But everyone shares the sidewalks, too. And we trade apartments, sometimes finding someone else’s peroxided hair between the floorboards. We fight over cabs (and Citi Bikes) and close elevator doors on one another. Every busy intersection is a kind of rat-king tangle: chance encounters, drag-out fights, families making their way, transactions and missed connections and hustlers of one kind or another pulling scams of one kind or another on rubes of one kind or another. Which means — look around — that we are always, constantly, starring in one another’s city. Guest-starring, at least. The woman behind the deli counter; the man who bumped into you outside, somehow ruining your day. The person from the subway you’ve been madly fantasizing about since. The one who passed the news to the friend of a friend who later got pinched for insider trading. The encounter in the bathroom of the bar, or the two college kids you watched kiss good-bye at Penn Station who came to mind again years later in the middle of the night. The woman at the dog walk you envy for her beauty; the neighbor you hate for having the apartment with the better view. The intimacies overheard on the street, the bodega-line pickup watched over by the manager. Six degrees of separation can feel like a joke. What connection requires more than three? We live on top of one another.

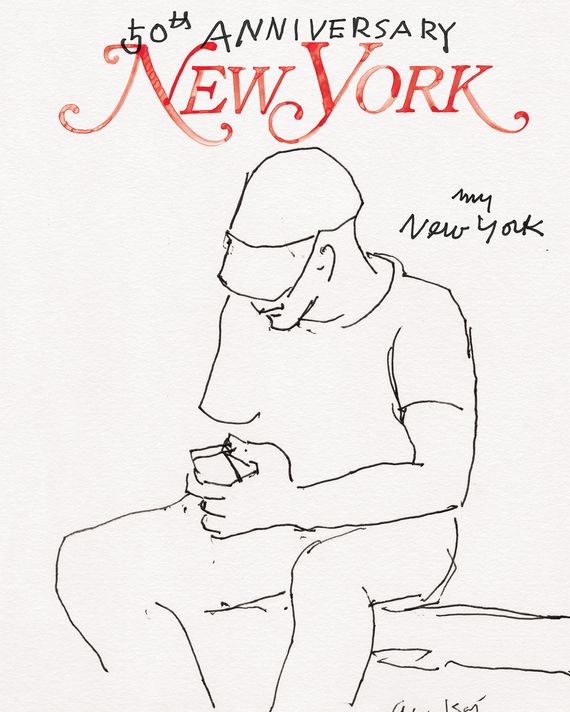

This anniversary issue is devoted to what might make other people in other places go crazy but here we call connection. Not just the connections we choose, like our poker groups or going-out friends, but those that could happen only in a city as clotted and manic as ours. Fifty years ago, New York’s founding editor Clay Felker wrote a mission statement for his new magazine. “We want to attack what is bad in this city and preserve and encourage what is new and good,” he wrote. “We want to be its voice, to capture what this city is about better than anyone else has.” Here, we return to this mission, attempting to capture the city’s voice through stories that are spoken as much as written, almost entirely in the first person, and always about how our disparate lives intertwine. We realize there are still barriers, of course — moats that divide New York into little islands. The city’s schools are the most segregated in the country, and there are those who rarely leave East New York or the Upper East Side. Nor do we live in a paradise of small talk and getting-to-know-you: Sometimes proximity is dreadful. But New Yorkers who spend their lives here, shoulder to shoulder with one another, cultivate an exquisite talent for close-quarters projection — every stuffed subway car a choose-your-own-adventure of imagined new friends and futures, every commute an excuse to daydream alternate lives.

And eavesdrop. In “The Enormous Radio,” John Cheever imagined a New Yorker tuning in to the sounds of those living stacked around her on all sides — above and below, just to the right and just to the left, a cramped apartment-house honeycomb of urban anomie and gossipy self-consciousness. As everyone who lives here knows, the device isn’t necessary: In most buildings, you don’t need a radio to listen in on the neighbors. And even those blessed with especially strong insulation are assaulted with new voices each time out the door. Inscribed by them, really, as you walk these streets; just open your ears and listen.