Editor’s note: This story first appeared in the December 23, 1968, issue of New York. It was also featured in Reread, New York’s subscriber-only archives newsletter. Click here to read the newsletter this appeared in.

One of the last big objects that symbolize power in New York is the private plane, on the order of a Lear jet or a Fairchild F-27. But even this all those millions of picky little bastids don’t understand … William Paley has a G-2 Gruman Gulfstream. Among the planes owned by the Rockefeller family are an F-27 Fairchild two-engine turbo-prop, a Jet Commander, and a twin-engine Beach Baron. Marion Harper had a DC-7 that cost $300,000 a year to maintain … yes … and that was precisely what all those small-minded picadors, stockholders in Harper’s advertising firm, Interpublic, picked on when they decided to force him out. The sheer morbid expense of it — but they never understand why these things are so necessary to men of power…

… the offal chomping grin…

… in New York. It is not because the private plane saves vital time by allowing Mr. Wonderful to take off for anywhere at a moment’s notice. Actually a private plane almost always loses time. Even three years ago private planes trying to leave in the afternoon from LaGuardia, Kennedy or Newark had to wait 45 minutes to half an hour for take-offs, because commercial airliners always had priority.

— but the offal chomping grin, friends —

And it is not because private planes save wear and tear on vitally important people or enable them to hold important conferences while in route, or go over vital data, and so forth. In fact, the cabins of most private planes are as cramped, crabbed and uncomfortable as a Sheraton hotel room, and the alleged air conferences almost never take place. Invariably the whole time is cluttered up with serving meals and fixing drinks.

But — the offal chomping grin, l tell you!

That’s what all those picky little bastids out there have never experienced in their lives — that magical moment before takeoff when the pilot and co-pilot come back into the cabin with these wonderful offal chomping grins on their faces and their little eyes open and round as friendly as a dog’s, and then their lips part and these yassah-massah voices begin, welcoming Mr. Wonderful and his guests and describing today’s flight plans and telling about the food and drink on board, all the while smiling their beautiful offal chomping grins —

— and it is at this point that it registers on everyone aboard, like a 50cc. injection of warm Karo syrup into the main vein … these are not the pilot and co-pilot with the comic strip profiles who rule your destiny on a commercial airliner even when you ride first-class, the ones who give firm orders one minute and then homespun talks on flying conditions the next, like stern parents trying a change of pace … no; these two are … chauffeurs! air butlers! servants, in a word — marvelous! — Captain Lackey, Co-lackey, and when you say move they will jump … and that, alone, in itself, justifies the executive jet in New York and makes it necessary and proper, that beautiful offal chomping grin — but how can all those picky bastids out there be made to understand?

One of the few powerful men who has spoken frankly on the subject is Senator Abraham Ribicoff. One night about 15 years ago he was talking to eight or ten students in the American Studies Club. The students got on the subject of what really drives people like congressmen and senators — fame? money? the exercise of power? So Ribicoff says: It’s not fame, at least not in the sense of publicity. They see their names and faces in the paper so often they take it for granted. It’s not money. There may be some congressmen with deals going, but most lose money while in office because of the cost of campaigning and entertaining. It’s not even the exercise of power, at least not in the sense of putting a bill through or having a part in policy decisions. For most of them it is something else. It’s more … seeing people jump. It’s a feeling … knowing that anywhere they go, people will move for them, give way, run errands, gather around … and jump …

Jump! Power is, after all, control over other people’s lives. So perhaps it is natural that the symbols of power — as opposed to mere fame or wealth — should involve people jumping, i.e., acting like servants or loyal vassals. This is more so that even today when New York is so full of rich men and celebrities who have access to the more obvious symbols of rank: e.g. publicity, expensively decorated apartments and townhouses, beach houses in the summer, country houses in the winter, big cars, big boats, art objects, Persian rugs, kids in private schools, and wives starved to near perfection in elephant-cuff pants. But as for the real thing … a mere celebrity, for example, may get preferential treatment in certain restaurants, but that is as far as it goes. As for really making people jump —

— it is subtle stuff to which many rich and well-known New Yorkers are even oblivious. They never really understood Bobby Kennedy, for example. In other areas his appetite for luxury was average or even restrained. But he derived enormous and, no doubt, enormously useful satisfaction from the real thing: seeing ’em jump. In his latter years, for example, he developed the habit of changing his shirt four or five times a day. Even allowing for his highly active schedule, this habit was incomprehensible to the people around him — except that it created an exquisite form of jumper in his retinue shirt bearer. Kennedy beckoned and the bearer brought him a new shirt. It was nice stuff! The most distinguished of the shirt bearers was reputed to be Manhattan lawyer and socialite William vanden Heuvel. Kennedy also enjoyed seeing aides like vanden Heuvel and others run down the street after his motorcade if they were late for the takeoff. There was no cruelty about this, however. After a block or so he would order the cars to slow down to take the man aboard. It was just routine seeing ‘em jump. Kennedy also put various members of his staff on weight loss regimens and would actually make them march up to the scale to see if they were sticking to their diets. This was regarded at the time as part of the Kennedy emphasis on physical fitness, although in fact it was another nice way to see ’em jump.

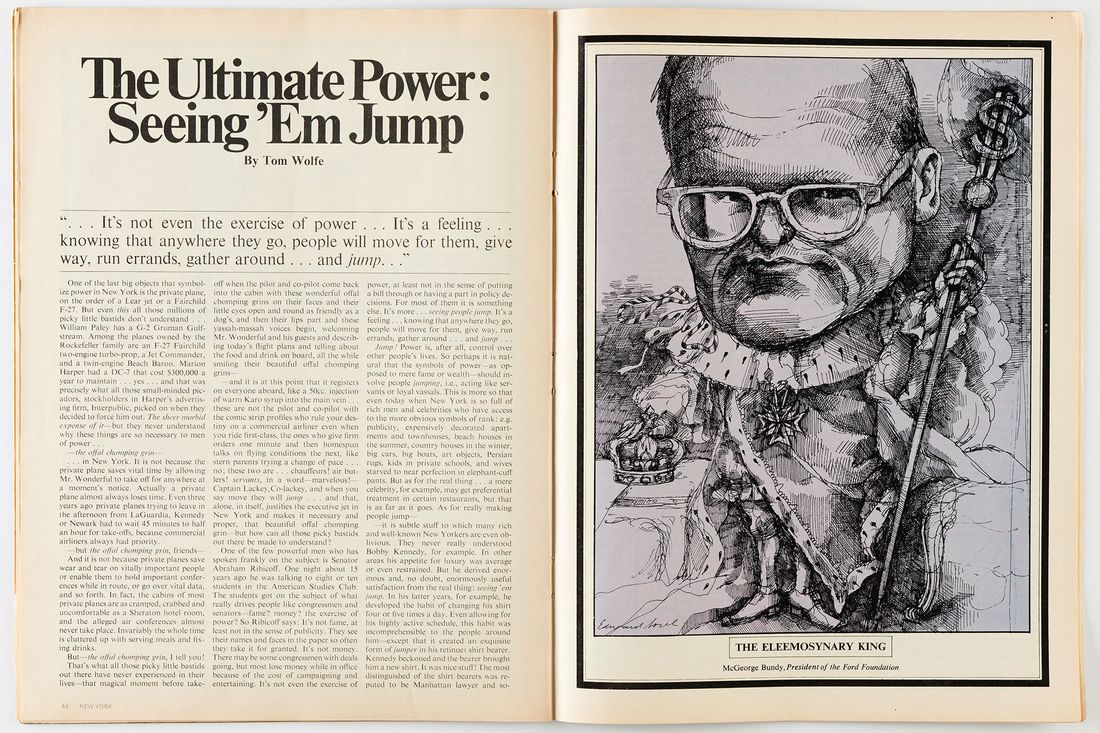

A more solid symbol for true men of power, however, is having brain jumpers around. Now this form of seeing ’em jump is well known in the highest circles of government as having a brain trust. In New York men of true power in private as well as political positions like to have brain trusters around, intelligent men they can summon, and see jump, at a moment’s notice. Like most status symbols, this one has a sound and practical origin. Today more than ever, information, rather than goods or personnel, is the most important resource of the powerful man. This is especially true in New York, where so much power, in all sectors, flows from the financial world. One of the great symbols of power currently is having an “eyes only” report — i.e. to be seen by the head man’s eyes only — waiting for you on your desk every morning, much in the manner of the morning reports distributed to top brass in the State Department, Department of Defense, CIA, ambassadors, and key officials in oil or defense-industry companies. It really doesn’t matter too much that a great deal of this information, even in the case of the CIA, tends to be lifted from the New York Times. Because very quickly the idea that he is at the center of a vast early-bird warning system becomes a psychological necessity to the powerful man in New York. This explains the significance of the radio telephones in the limousines that so many powerful New York executives still insist on, despite the fact that outsiders can easily intercept messages, making the phones useless for sensitive conversation. But so what! The car phone is … an information totem. The very king of information totemism, by the way, is Aristotle Onassis. In those marvelous pictures Onassis likes to have taken aboard his yacht — the ones where he has his shirt off and a great tire of fat enveloping his waistband — he always has a telephone to his head and more on the desk in front of him and a Telex machine to one side and various receiving sets in the background — so many brains jumping for the Early Bird!

Many men of power in New York have informal brain trusts, experts of various sorts whom they like to convene to discuss critical problems. The brain jumpers they call in may very well be younger men from outside their own fields — even from journalism or show business. There’s no money involved. The brain jumpers get their satisfaction from the feeling that they have somehow hooked into the power circuit. The man of power gets useful information … sometimes … and always the satisfaction of seeing well-bred brains jump in his behalf. Over the years the Rockefeller brothers have actually institutionalized this sort of operation, setting up ostensibly independent information-gathering organizations and hiring experts at heavy salaries.

As for the daily life of the powerful in New York … they strive not only for insulation from the public — almost every wealthy New Yorker tries for that — but for various nostalgic trappings of European feudalism, which is, of course, the most venerable form of seeing ’em jump. They tend to live almost exclusively in large cooperative apartments on upper Fifth Avenue (“Central Park East”), Park Avenue, East 57th Street and Sutton Place, or in their own townhouses in the East 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s, and low 90s. The older co-ops are really more like feudal bastions than the townhouses. They have amazingly large staffs of doormen and janitors and ingenious walls of privacy. On each floor the elevators tend to open up on a small vestibule, which is the outer chamber of only one apartment. Unlike the new U.N. Plaza building — which is more Show Biz than Power — the older buildings have no mail boxes. The mail is sorted by the house staff and delivered to the door. The doormen tend to be aging servitors of English stock and feudal-service disposition. They never engage a tenant in conversation unless invited to do so, and indulge in no personal remarks even then. They run interference, carry bags and chase cabs with a feudal zeal despite their years. They are almost always starchily turned out in wing collar, white tie and military frock coat. Somehow in non-Power co-ops, no matter how expensive, the wing collar gives way to an ordinary turned-down collar; the doormen themselves are ethnic, as it is called, meaning Irish, Italian, Puerto Rican or something else non-English; and they may engage in direct conversation at any moment. At the bottom of the Power scale are the West Side co-ops, where the doormen never seem to be able to pull the full uniform together at any one time. If they have on the jacket, they have on baggy gray khakis below. If they have on both the jacket and pants of the uniform, they have on no tie, or else the jacket is dangling open. What a world …

Many wealthy New Yorkers travel around the city by limousine. But the most powerful tend to engage in a kind of British reverse snobbery, using old or inconspicuous cars. David Rockefeller is driven about in an old Buick; Jock Whitney, in an old green Chrysler; Averell Harriman, in an old Mercury. The late Cardinal Spellman had a private black Checker. Black Cadillacs are still common, but Rolls-Royces, among the powerful, are looked down upon as vehicles for women or Show Biz jaybirds. Jaybirdism is avoided by men of power of New York at all costs. They may wear their hair on the longish side, but it will be combed straight back and there will be no sideburns. Sideburns are a very strong dividing line between the powerful and the nearly celebrated. They also avoid all mod or Cardin-style clothing. English custom-made suits of hard worsted used to be a hallmark of men of power in New York. But now the jaybirds – chiefly people in communications or show business — have discovered English tailoring, and men of power currently tend to concentrate on three articles of dress: shirts, ties and shoes. The shirts are usually custom made at $25 to $40 apiece. The collars have straight points and no gap above the button. Ties are almost invariably a solid color, and usually dark blue. Prints and even stripes smack of juvenilism, collegiatism or jaybirdism. In shoes they look for the “old leather” look of English bench-made shoes. They prefer capped toes and avoid heavy soles, which smack of collegiatism.

At their offices, elevators have great symbolic significance, since elevators in large buildings are places where it is easy to be trapped with the public. Where the buildings have elevator men, they are instructed to close the door and ascend as soon as certain VIPs step in. The very top NBC executives, for example, enjoy this sort of jumping in the RCA Building in Rockefeller Center. A very few New York executives have the ultimate symbol, a private elevator in a large building. One of the final inducements offered to Bennett Cerf to get him to agree to move Random House out of the Powerhouse mansion at 457 Madison over to the new building going up at 205 East 50th St., reportedly, was the promise of a private elevator. Bobby Kennedy had a semi-private elevator for his five-room pied-à-terre in the United Nations Plaza building. It served only his duplex apartment and two others. Where the elevators are automatic, the problem requires more ingenious solutions. In the Time-Life Building the starters were instructed to put Henry Luce’s elevator on “go” as soon as he stepped in. The first stop in this bank of elevators was his floor, so that the system was almost private. (At 40 Wall Street one elevator serves only the 17th and 18th floors, the offices of Kuhn Loeb, which is corporate privacy at least.) The rationale for all this is that the time of top executives is exquisitely valuable. In point of fact, of course, it is to see ’em jump.

Men of power in New York tend to give their offices the look of an expensive home, preferably that of a medieval baron’s. The look they strive for is not Knoll Associates, but French & Co. In the classic mode, the carpeting is not wall to wall but Persian. The furniture runs to antiques. This is partly because men of power tend to look upon antiques as a sound investment that increases in value with time, but chiefly is psychological. Antiques smack of feudal power, for a start. But chiefly the general look of an expensive home suggests the idea of a man of power as a paternal ruler, an absolute monarch, whose power is not corporate but personal. In the new CBS building, a strict corporate rule controls the decor of every office but one, giving the building an absolutely uniform look of Eames-Saarinen-Florence Knoll modernity. The one exception, of course, is the suite of CBS President William Paley, which is furnished … yup … completely in antiques (he also has a private garage door in the base of the building).

The office suites of the very powerful typically include one or more bedrooms, private bathrooms and a dining room. The private dining rooms are perhaps an even more potent symbol of power than private elevators. The man of power in New York does not even go out to a private club for lunch. He tends to have a rather baronial dining room with full staff of maids, butlers and the chef. Some corporations, such as Chase Manhattan on Wall Street, have even gone into competition with Manhattan’s leading restaurants to obtain top chefs for their top executives. The ultimate is Lehman Brothers at One South Williams St., whose reigning patriarch, Bobby Lehman, is one up over the entire field. Not only does he have a private dining room for the firm’s important executives and guests, but also another for himself alone. The daily question at Lehman Bros. is: “Is Bobby coming down or is he dining alone?”

See ’em jump … for one alone …