Derek Jeter entered the Yankee Stadium interview room in his undershirt. It was a customized undershirt, dark blue with the white logo of his personal Nike brand. But it was not his home jersey, the white one with dark-blue pinstripes. He’d taken that off for the final time.

Jeter looked completely spent. He had been feted and lauded for seven months. He’d appreciated all the praise even as he’d tried to block it out, to tell himself that it really wasn’t about him, it was about the fans. But what had really worn him down during the farewell tour was the act of trying to deny that the end of his playing career was closing in. Now he couldn’t deny it anymore. He had allowed himself one great moment on the field after the game, walking out to shortstop. It was a shame that two cameramen had to dog his every step. He deserved to be out there alone on the dirt, with the cheers and the chants washing over him.

Afterward, Jeter talked about how the past few months had started to feel “like a funeral.” The Yankees have always been a bit death-obsessed, the ghosts of Ruth and Gehrig and Munson and the rest chilling as well as inspiring, the half-black visage of the late George Steinbrenner hovering behind right-center field. For the past few years, Jeter has walked to the plate with an introduction from the grave, the recorded voice of the late Bob Sheppard, a neat way of honoring history, but also kind of spooky. And after the ridiculously joyous ending — the Orioles tying the game in the top of the ninth seemingly scripted to deliver one more dramatic Jeter triumph — he spotted a group of his retired teammates and close friends — Jorge Posada, Andy Pettitte, Mariano Rivera, Tino Martinez — lined up and waiting, as if to welcome him to the other side.

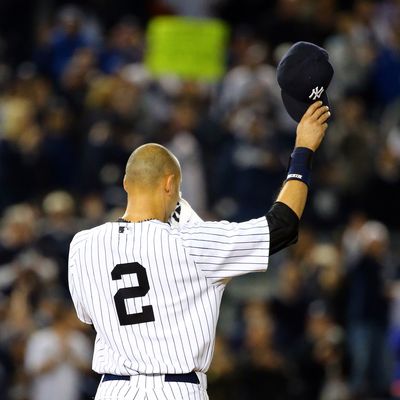

Through the fatigue and the near tears, Jeter couldn’t help but smile. He hadn’t dared dream this ending, even if he said he felt he’d been living a dream all these years. He tugged at his hat to keep from crying and teased the reporters one more time for not asking the right questions to make him lose his composure. Yes, this wasn’t a World Series–winning homer; the Yankees had been eliminated from playoff contention on Wednesday, so this game didn’t “mean” anything. But it was pretty cool, and it was another win, the thing that had driven Jeter for 20 years, and he was reveling in the thrill of delivering victory one more time.

In October, 1964, the great Roger Angell wrote: “Baseball is a commercial venture … [but] the ability to find beauty and involvement in artificial commercial constructions is essential to most of us in the modern world; it is the life-giving naïveté.” Now, closing in on October 2014, we’re even more wised up about the big, often ugly business of sports. Derek Jeter is a rich man, and he was playing in a billion-dollar stadium full of overpriced seats. Underneath those seats, down in the clubhouse after midnight, in Jeter’s locker, the hangers were empty. You hoped his No. 2 hadn’t already been bagged and tagged for sale to the highest bidder. You hoped Derek Jeter got to take that jersey home with him, the way he’d given fans one more improbable memory, a bit more of the life-giving naïveté, to take home with them for the winter.