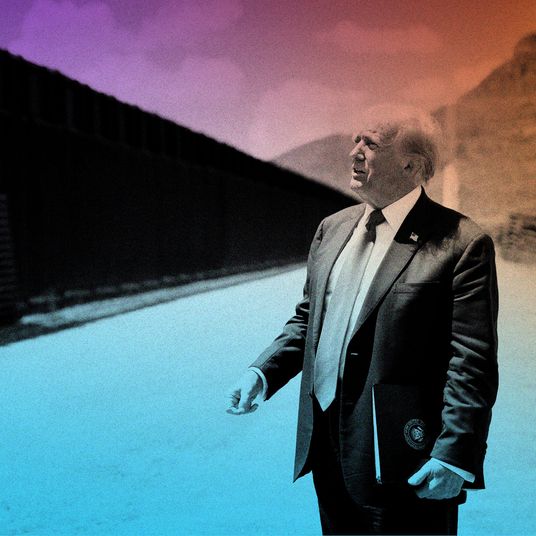

One of the lesser perils of Donald Trump’s candidacy is that it threatens to lower liberals’ expectations for their own political leaders. On Monday, the Republican nominee called on Americans to distrust all Muslims and stockpile firearms, for the sake of national security. Next to the mogul’s mendacious jeremiad against non-European immigration, Hillary Clinton’s reflections on the attack in Orlando were a model of civic responsibility. But we should resist the impulse to grade on that curve.

There was much to admire in Clinton’s remarks: her condemnation of anti-Muslim rhetoric and the violence it inspires; her insistence on placing the Orlando attack in the broader context of LGBT Americans’ long struggle for acceptance; her championing of social equality as a powerful weapon in the fight against radicalization. But the Democratic nominee closed her speech with an admonition that the American people would do well to reject.

I remember how it felt, on the day after 9/11, and I bet many of you do as well. Americans from all walks of life rallied together with a sense of common purpose on September the 12th and in the days and weeks and months that followed. We had each others’ backs. I was a senator from New York. There was a Republican president, a Republican governor, and a Republican mayor. We did not attack each other. We worked with each other to protect our country and to rebuild our city.

President Bush went to a Muslim community center just six days after the attacks to send a message of unity and solidarity. To anyone who wanted to take out their anger on our Muslim neighbors and fellow citizens, he said, “That should not, and that will not, stand in America.” It is time to get back to the spirit of those days, the spirit of 9/12. [emphasis added]

Nostalgic tributes to the days immediately following the worst terrorist attack in our nation’s history have always been a bit obtuse. For many of those directly affected by the attacks, the spirit of 9/12 was not characterized by a sense of unity, but by the sense of isolation that attends unspeakable loss. But the primary problem with these tributes is not that they ask those most traumatized by 9/11 to summon fondness for its aftermath. The problem is that — to the extent Americans did experience a spirit of national unity in those weeks and months — that spirit paved the way for a set of disastrous policies whose consequences we are still suffering from. And there is little reason to think that a return to a sense of unity premised on collective terror would advance progressive goals rather than authoritarian ones.

Certainly, Clinton here invokes “the spirit of 9/12” for a more progressive purpose than Glenn Beck did in 2009. And a return to the Republican Party’s political norms before the rise of Trump — when a GOP president felt comfortable communicating his solidarity with American Muslims — would be desirable. But the legislation American politicians unified behind to “protect our country” in the wake of the attacks undermined the civil liberties of American Muslims and increased the stigma that they live under. The Terror Watchlist took away thousands of American Muslims’ right to travel into and out of their country without any form of due process. The Patriot Act allowed the FBI to subject Muslim-American communities to surveillance and routine interrogations. On Monday, Clinton decried Trump’s suggestion that “we have to start special surveillance on our fellow Americans because of their religion.” But in New York City, the spirit of 9/12 led the local police to do precisely that, forming a “demographics unit” that infiltrated mosques, Muslim cafés, restaurants, and student associations. (The unit was recently dissolved in the face of legal challenges.) Outside the halls of power, the spirit of 9/12 proved was no less toxic. According to FBI data, there were 481 hate crimes against Muslim and Arab Americans in 2001 — up from 28 the year before. (That number has steadily increased in the years since.)

During the broader post–9/11 policy debate, the spirit of national unity neutered dissent to the invasion of Iraq, a war that bought us regional instability and a strengthened Iran at the cost of trillions of dollars and hundreds of thousands of lives. In those days, Phil Donahue hosted one of the highest-rated shows on MSNBC. But he was also one of the few voices in cable news who opposed the war and the network’s executives felt this divisive dissent was an affront to the spirit of 9/12; in early 2003, he was taken off the air. Meanwhile, the New York Times honored that spirit by plastering the Bush administration’s dire claims about Saddam Hussein’s machinations across its front page, and after subsequent reporting brought the validity of those claims into question, the paper buried such divisive information where only traitorous newshounds would read it. One would think that Hillary Clinton, of all people, would remember the suppressive aspects of our post–9/11 political “unity” — it was in that very climate, after all, that she cast the vote on Iraq that cost her the nomination in 2008.

On Monday, Clinton posited the spirit of 9/12 as a countervailing force to the anxious divisions that Donald Trump sows. But that spirit produced the forerunners of the kind of domestic discrimination — and destructive, amoral foreign policies — that liberals rightly fear a President Trump would pursue.

Democrats do need to counter Trump’s hateful message with appeals to national unity. But they should find a foundation for that unity that’s more conducive to progressive politics than our collective vulnerability to terror. One of the most concrete legacies of the post–9/11 political moment was a dramatic shift in federal spending toward defense and intelligence. The Pentagon’s base budget increased 43 percent (accounting for inflation) in the ten years after the attacks. In 2011, the federal government could have secured Medicare’s solvency over a 75-year time horizon by reallocating just one-fifth of that increase in annual defense spending. This is only one measure of what could have been gained if the political unity of the early ‘00s had been founded on a shared commitment to eradicating poverty instead of terrorists. But the cost of the post–9/11 moment to liberal priorities should also be measured in what was lost: The deficits produced by the Pentagon’s runaway budgets gave oxygen to the GOP’s crusade for austerity, which produced the spending sequester and cuts to a food-stamp program that was already too meager to keep American children from experiencing malnutrition.

All of which is to say: The post–9/11 mood was bad for progressive politics, and Democratic presidential candidates shouldn’t be encouraging America to return to it — especially, when there is so little cause for evoking the fear that defined that awful time.

The Orlando shooting was not 9/11. As horrifying as the attack was, it is a mistake to elide the distinctions between the threat posed by disaffected young men radicalized by propaganda and that of well-organized, well-funded terror cells. In a nuclear age, the latter have the potential to do catastrophic harm. A man with an AR-15–style gun and an internet history full of ISIS propaganda can destroy lives, but he cannot obliterate downtown Manhattan. Other than making assault weapons more difficult to access, there is little the government can do to prevent any individual psychopath from committing mass murder — no matter his ideology. Attempts to eliminate that risk will doubtlessly erode civil-liberty protections at the expense of politically disempowered minorities.

Thankfully, lone wolf terrorists simply don’t represent that significant of a threat. The number of Americans killed by such individuals is a minuscule fraction of the number killed by other forms of gun violence.

Responsible politicians should not encourage the public to associate the threat posed by individuals like Omar Mateen with that posed by Al Qaeda circa 2001. And Clinton did more to hype the threat of lone wolf terrorists than employ an unfortunate analogy; she promised to make “identifying and stopping lone wolves” a “top priority” of her administration; called for a drastic increase in intelligence resources to counter the threat; and for an expansion of the Executive Branch’s power to revoke rights without due process by banning those on the Terror Watchlist from purchasing firearms.

Perhaps it would be political malpractice for Clinton to characterize the threat in other terms. Public opinion demands a “muscular” response to acts of mass murder on American soil. Considering the stakes of November’s election, it is difficult to fault Clinton for pursuing the politically expedient.

But those of us who do not look fondly on the policy legacy of the early George W. Bush years must resist any return to “the spirit of 9/12.” Even if Trump never gets any closer to the Oval Office, voters must guard against the counterproductive policies that collective fear is liable to produce. The GOP nominee’s worst instincts are not unique to him. Liberal Democrats’ patron saint oversaw Japanese internment. There is still nothing so fearsome as fear itself.