There is a sort of unstated belief in critical assessments of both presidential candidates that their more ambitious plans will be stymied by the same kind of congressional gridlock that has so regularly frustrated Barack Obama. With respect to Donald Trump, the big fear has been that he will simply ignore constitutional restraints on the presidency and govern like the kind of despot he so obviously admires.

If Trump is elected, Republicans are likely to maintain control of the Senate and will definitely control the House. You do not have to resort to banana-republic analogies to find a scenario in which large and damaging things happen very quickly, and through the old-school process of legislation passed by Congress and signed into law by the president. So long as Republicans have 50 senators, an awful lot of the very large common ground shared by Trump and the GOP can be enacted via the filibuster-proof budget-reconciliation process, and even more can be enacted if (as is likely) Republicans more or less abolish the filibuster itself to reduce Democrats to an impotent backbench, like they are in the House.

A lot of very smart people don’t quite seem to grasp this. The current issue of The New Yorker features a long and otherwise well-researched piece by Evan Osnos covering the early phases of a hypothetical Trump presidency from all sorts of angles. Here’s what Osnos says about legislation:

Some of Trump’s promises would be impossible to fulfill without the consent of Congress or the courts; namely, repealing Obamacare, cutting taxes, and opening up “our libel laws” that protect reporters, so that “we can sue them and win lots of money.” (In reality, there are no federal libel laws.) Even if Republicans retain control of Congress, they are unlikely to have the sixty votes in the Senate required to overcome a Democratic filibuster.

Actually, cutting taxes and at least disabling Obamacare — along with other funding-related matters like block-granting Medicaid and SNAP, eliminating other forms of “welfare,” boosting defense spending, shifting subsidies to favored fossil-fuel energy sources, and killing federal support for Planned Parenthood or other “anti-family” entities — can easily be accomplished by packaging it all in a budget-reconciliation bill, which can be enacted by the Senate under filibuster-free procedures. (The modern use of budget reconciliation began in 1981 when Ronald Reagan achieved much of his domestic-policy agenda in two bills.) Party discipline on such a measure would be viciously enforced. And while it is true a funding nexus is necessary before an item can be included in a reconciliation bill, it is not that hard to find indirect ways to “defund” enforcement of laws and regulations Congress does not like, and in close cases the Senate parliamentarian — who works for the majority party — can make friendly rulings.

In fact, the odds are very good that a Republican Senate dealing with a Republican House and a Republican president will kill the filibuster entirely in the pursuit of a legislative blitz designed (along with the executive actions Osnos writes about) to eliminate the Obama administration’s legacy almost entirely. As my colleague Jonathan Chait has explained, the filibuster (already abolished by the last Democratic-controlled Senate for executive-branch and sub–Supreme Court judicial appointments) has survived the last few years only to the extent it was made moot by other roadblocks like divided control of Congress and a presidential veto. With both Houses of Congress and the White House pulling in the same direction, the filibuster will inevitably be eliminated to grease the skids, beginning with an instant measure to confirm a right-wing Supreme Court justice to replace Antonin Scalia — the very foundation of the Trump alliance with movement conservatives — and then the filibuster reform will be extended to regular legislation. If traditionalists complain, Republicans will shrug and point at Harry Reid as the fiend who violated the sacred mores and folkways of the Senate with his limited version of filibuster reform, making its consummation a matter of course.

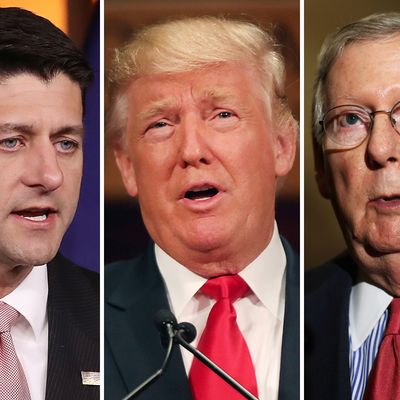

It is true that if Hillary Clinton wins the presidency and Democrats win both Houses of Congress, they, too, will “ram through” legislation via budget reconciliation and radical filibuster reform. With the presidential race tightening, however, the odds of a Democratic trifecta have dropped significantly. It is far more likely that Clinton is the one who could face the kind of legislative gridlock we know so well from the post-2010 Obama presidency. Sure, congressional Republicans could “rein in” Trump to some extent on the topics where they don’t see eye to eye: I doubt Paul Ryan and Mitch McConnell are going to go for any big infrastructure spending initiative or a major attack on corporate subsidies. And they might try to interfere with his desire to revoke most of America’s trade deals and other diplomatic arrangements.

But make no mistake, “plague on both your houses” pundits and voters: The Trump-Ryan-McConnell common ground is broad and radically reactionary, and it is a lot closer to realization than Hillary Clinton’s agenda. Within just a few months we could see the final confirmation of a prophecy made by Nixon Attorney General John Mitchell back before he was sent to the hoosegow for his role in Watergate: “This country is going so far to the right you won’t recognize it.”