Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid told veteran New York Times reporter Carl Hulse that, if his party wins back the majority, it might completely eliminate the filibuster. This threat has been received as a revelatory and potentially explosive new development. The reality is that the filibuster is already dead de facto, and only political circumstance will dictate when the Senate formally kills it de jure.

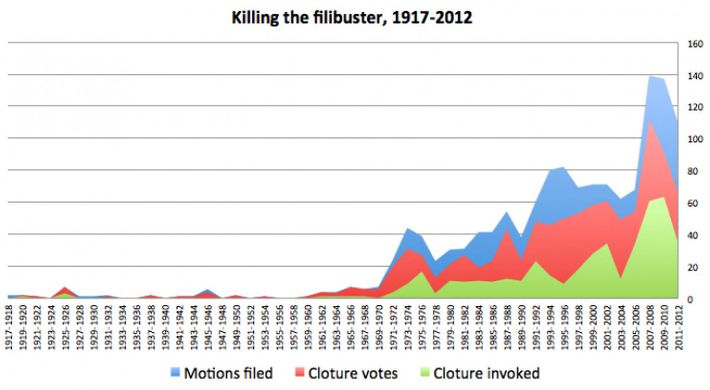

It is widely believed that the filibuster is part of the founding design of two legislative chambers, reflecting the Senate’s purpose as a slower-moving chamber for lengthy debate. In fact, the filibuster was a pure mistake, arising from confusion over rules in 1806 and created by Aaron Burr. Senate leaders have struggled to deal with it on and off. Over time, they imposed different supermajority levels that could cut off debate — a two-thirds vote, then 60 votes. Informal norms meant that members only used the filibuster on rare occasions — during the 20th century, it was mostly used by Southern Democrats to block civil-rights legislation. Beginning in the 1990s, it had evolved into a routine supermajority requirement, something it had never been before.

Republican leaders threatened to eliminate the filibuster for judicial nominations during George W. Bush’s second term, a threat that forced Democrats to back down and allow Bush to appoint nearly all of the judges he wanted. During Barack Obama’s second term, Democrats, now in the majority, threatened the same rule change when Republicans blocked several judges and Executive branch appointments. This time Republicans refused to back down, and the conventional wisdom held that triggering the rule change would devastate the culture of the Senate, which is why people called it the “nuclear option.” That conventional wisdom has held to this day. “Eliminating the filibuster on legislation or Supreme Court nominees, who were not included in the 2013 changes, would be an earth-shattering transformation in the culture of the Senate,” writes Hulse in the Times. “Any attempt to abolish or significantly scale it back would, without doubt, provoke a furious partisan fight.”

In reality, nothing of the sort happened. Democrats benefited overwhelmingly from the rules change and endured no important blowback. The only retaliation Republicans could have tried would have been to withhold cooperation, but cooperation had already been withheld.

Now, Reid’s rule change was narrowly tailored to address only Executive branch appointments and judicial nominees for federal courts other than the Supreme Court. Why did he eliminate the filibuster for those positions only? Senate Democrats argued that Republican obstruction of those vacancies was unusually aggressive, which is true — Republicans were leaving agencies without a leader because they objected on principle to confirming anybody at all, an unprecedented use of the filibuster. But, mainly, those positions were the only places where the Republicans had a veto point over the Democrats’ agenda. In 2013–14, Democrats had the presidency but not the House. They could appoint judges and administrators to the Executive branch. Because Republicans held the House, they could not pass major legislation. And they could not confirm Supreme Court appointments because there were no vacancies during that period.

Reid changed the rules to eliminate the filibuster in the only places where the filibuster stood in the way of his party getting things done. There is no reason to think he or any other Senate leader will ever let the filibuster prevent his party from getting things done.

If Republicans win the presidency and keep control of the Senate, they will eliminate the filibuster in order to enact their agenda. Hugh Hewitt, the Republican talk-show host who has interviewed McConnell extensively, practically admitted as much:

When Hewitt says “prudence” prevents McConnell from promising this explicitly, he means that McConnell wants to be able to weep bitter tears of anguish if Charles Schumer,* who will succeed Reid when he retires this fall, happens to be in the position to change the rules for Democrats’ benefit before McConnell has the chance to change them for Republicans’ benefit.

What happens to the filibuster will be dictated by the results of November’s election. If Republicans keep the House but Democrats gain the Senate and the White House, Democrats will eliminate the judicial filibuster for Supreme Court seats. The legislation filibuster will stay in place because it will be irrelevant — any deal Democrats could make that could pass a Republican-controlled House could also get 60 Senate votes anyway. If Democrats gain control of the House and Senate along with the White House, Republicans will use the filibuster to block everything they do until Democrats eliminate the filibuster for all legislation and judicial nominations. If Republicans win the presidency, House, and Senate, they will eliminate the filibuster.

If you think I’m looking at this too cynically, remember that I predicted in 2014 that, if a Supreme Court justice died during Obama’s last two years and Republicans held the Senate, they would refuse to confirm any replacement. Many people dismissed this as “preposterous.” But that is what happened. And it happened because we have entered an era of party government.

*Update: This sentence originally said Reid would change the rules.