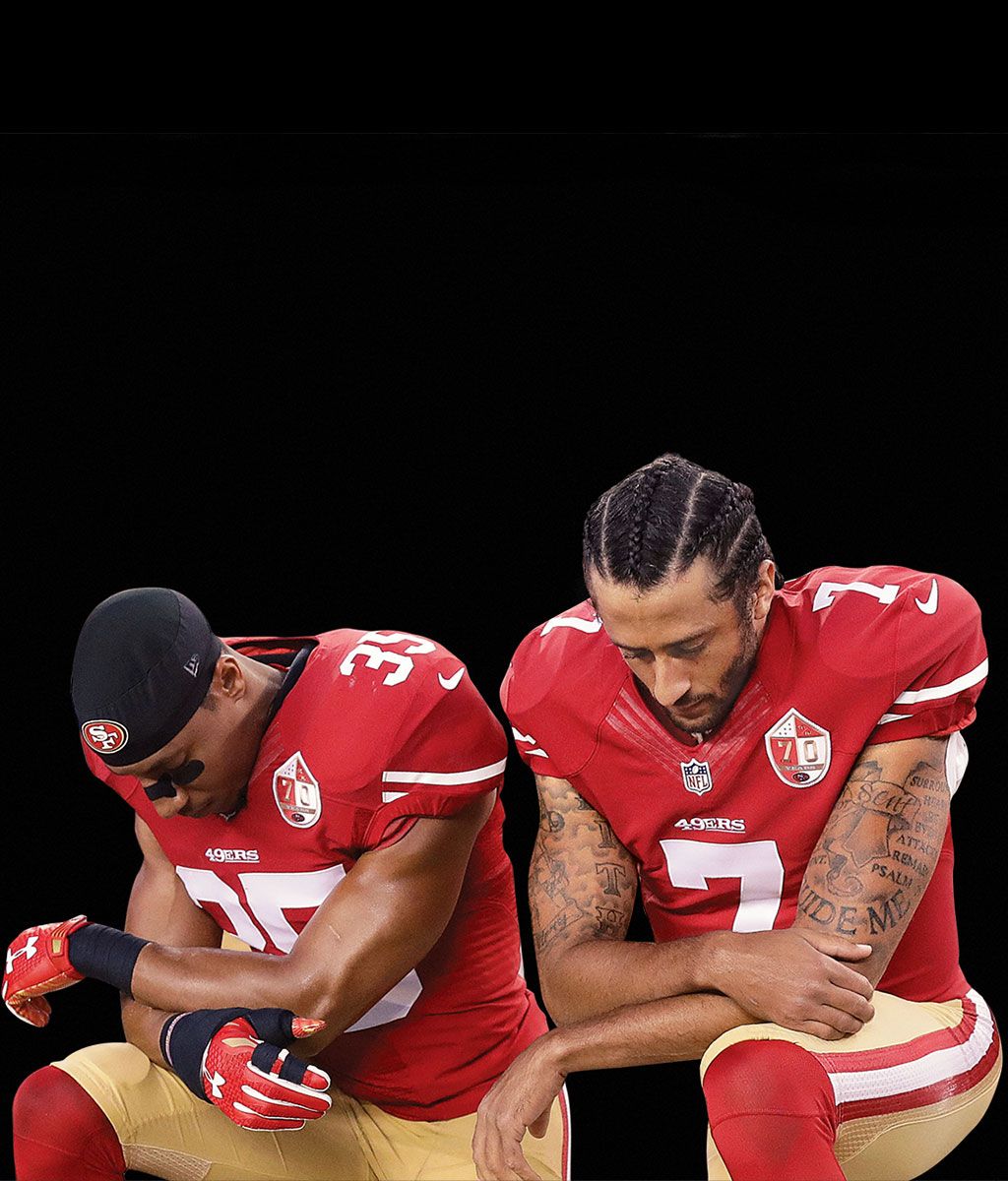

Late last year, George Gittens, who goes by Dr. Natural, got a call from Nessa Diab, the host of Hot 97’s afternoon show. Dr. Natural is a holistic-health advocate in Brooklyn who has long dreadlocks and maintains a raw, vegan, alkaline diet. Diab was hoping Dr. Natural would speak at an event she was putting on with her boyfriend, a professional football player. “I said, ‘Cup-ernick?’ ” Dr. Natural said recently. “ ‘Who’s Cup-ernick?’ ” Diab clarified that her boyfriend was the San Francisco 49er who had knelt during the national anthem to protest racial injustice and police brutality in America, causing dozens of other athletes to join him in solidarity and then-candidate Trump to suggest he find another country. “I didn’t know his name,” Dr. Natural said. “I just knew him as the guy who took a knee.”

Early on the Saturday of Martin Luther King Jr. weekend, Colin Kaepernick, the guy who took a knee, walked onto a stage at the Audubon Ballroom, on West 165th Street, flanked by a floor-to-ceiling mural depicting Malcolm X. Kaepernick was hosting his second Know Your Rights Camp, and explained the venue’s significance to the 240 young people in attendance: In 1965, Malcolm X was assassinated here while delivering a speech of his own. “There’s a lot of people out there that don’t want to see you succeed,” Kaepernick told the crowd. “But the people in this room do.”

Kaepernick was joined by three of his 49ers teammates at the all-day event, which covered the intersectional bases of modern activism. In addition to Dr. Natural’s presentation on the environmental importance of filtering your water and using a squatty potty, there were sessions on the history of policing, financial literacy, and college admissions. Carmen Perez, the executive director of Gathering for Justice, to which Kaepernick had recently given $25,000 as part of his pledge to donate a million dollars to social-justice organizations across the country, led a role-playing exercise for engaging with police. Dr. Natural didn’t believe Diab when she said they could get more than 200 kids to show up on a Saturday morning, so he hadn’t brought enough pamphlets on “maintaining a positive mental attitude.” “I’m sure some of the motivation was to meet Kaepernick himself,” Dr. Natural said. “But, hey, whatever works.”

Throughout the sessions, Kaepernick sat to the side, listening and taking notes, before returning to the stage to present the campers with several items to take home: swag from his endorsers (Nike backpack, Beats headphones), paperback copies of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, guides to eating vegan in New York — Kaepernick gave up meat and dairy a year ago — ancestry.com subscriptions to trace their roots, and T-shirts matching his own, which read I KNOW MY RIGHTS on the front and listed ten of them on the back, including YOU HAVE THE RIGHT TO BE BRILLIANT.

It had been five months since Kaepernick first sat during “The Star Spangled Banner,” and the Audubon was many literal and figurative miles from the 70,000-seat NFL stadium where he launched his protest and from the cover of Time magazine, where he ended up. But the aftershocks were everywhere. The NFL playoffs were then careering toward a Super Bowl in which the two teams came to personify America’s sociopolitical fissures — the winning Patriots, led by friends of Donald Trump, and the Falcons, from Atlanta, where more than half the city’s population is black — and many of the commercials seemed to have been cooked up in a social-justice seminar rather than an ad agency. None of the players protested the anthem, but half a dozen Patriots, so far, have broken with the story line that their team equals Trump, and have said they won’t attend the White House celebration of their victory because, as one of them put it, “I don’t feel welcome in that house.”

After decades of professional athletes largely choosing, as LeBron James put it, in 2008, “to keep athletics and politics separate,” Kaepernick’s protest was a culmination of several years in which they had begun to do just the opposite. In some ways, the superstars were just waking up alongside their generation, particularly as Black Lives Matter ushered in what now looks like the country’s most significant protest era in decades. But athletes also have enormous cultural and economic influence, and have started to understand how to leverage that for something more than selling sneakers. Leagues, teams, and brands are trying desperately to keep up. Earlier this month, when Under Armour’s CEO called Donald Trump “a real asset” to the country, Stephen Curry, the Golden State Warriors star, whom Morgan Stanley has estimated to be worth as much as $14 billion to Under Armour, told the press he agreed with the assessment, “if you remove the ‘-et.’ ” After Curry spoke to Under Armour’s CEO, the company released a statement walking back its support. “If I can say the leadership is not in line with my core values,” Curry explained, “then there is no amount of money, there is no platform I wouldn’t jump off.” A few days later, Nike released a 90-second ad called “Equality,” in which Serena Williams, Kevin Durant, and LeBron James appear in black and white as Michael B. Jordan asks, “Is this the land history promised?” Nine years after James spoke of a separation between sport and politics, he stood on a basketball court in Nike gear and made clear that times had changed. If we can be equals here, James said, at center court, “we can be equals everywhere.”

When Kaepernick’s protest first landed on the front page, in late August, and he suddenly became America’s most famous — and controversial — activist, he went looking for help. His path to activism had been a lengthy one, urged along by Harry Edwards, a UC Berkeley sociologist who consults with the 49ers on diversity issues and had been encouraging him to read James Baldwin and others as a way of educating himself. No one had noticed when Kaepernick spent much of the previous year posting Malcolm X quotes and social-justice memes on Instagram, or when he sat for the anthem during the 49ers’ first two preseason games. But after a reporter got a tip from a team official and asked Kaepernick about it — “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color” — the quarterback found himself at the center of a firestorm. Kaepernick talked to Edwards, and Diab, who had long been outspoken on policing and other issues, put Kaepernick in touch with, DeRay Mckesson, of Black Lives Matter. Michael Skolnik, an activist in Brooklyn who often helps celebrities figure out how to become effective activists, talked to Kaepernick two days after his protest. “The first thing I saw was that he knew his shit,” Skolnik said. “What he didn’t know was that the movement has multiple layers of work, so the question is, where do you want to be involved?” Kaepernick told Skolnik that, for starters, he wanted to donate a million dollars. “I said, ‘Okay, that’s nice,’ ” Skolnik said. “ ‘But don’t think your million dollars is gonna stop cops from killing black people.’ ”

Kaepernick also talked to the Knicks’ Carmelo Anthony, who has quietly become one of the sports world’s most socially conscious stars. After the 2015 death of Freddie Gray in Baltimore, where Anthony grew up, he went to Maryland and joined a protest in the streets. “Well, you’re courageous,” Anthony says he told Kaepernick. “But now is the hard part, because you have to keep it going. So, if that was just a onetime thing, then you’re fucked.”

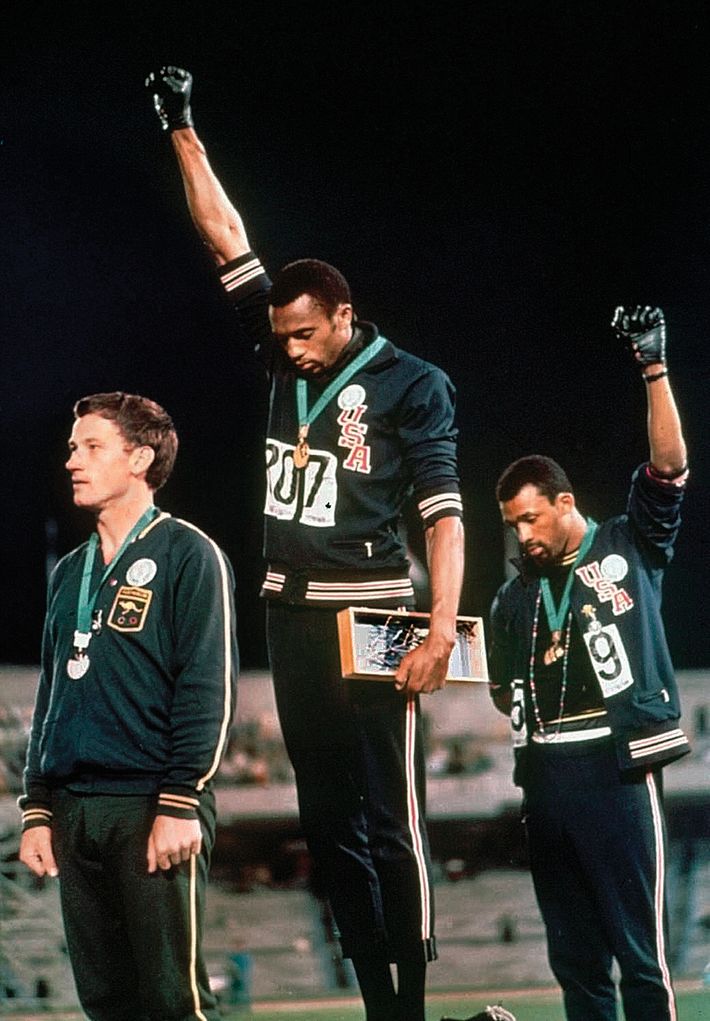

There is a rich and varied history of athlete activism, from Jackie Robinson, whom Martin Luther King Jr. credited with helping to launch the civil-rights movement by integrating baseball in 1947, to Tommie Smith and John Carlos, whose radical Black Power salutes at the 1968 Olympics became the most iconic sports-meets-politics moment of the 20th century — in part because activism soon faded in sports, as it did nationwide. After the ’60s, athletes waged battles for higher pay and better treatment, but campaigns for off-the-field issues were rare. Athletes became brands, and brands didn’t do politics. “If I stand on a platform, I’m gonna be speaking for O.J.,” said O. J. Simpson, the most famous black athlete of the 1970s, referencing Smith and Carlos’s Olympic protest. In 1990, Michael Jordan declined pleas from Arthur Ashe and others to endorse Harvey Gantt, a black candidate for Senate in Jordan’s home state of North Carolina, despite the fact that he was running against Jesse Helms, a notorious racist. “Republicans buy sneakers, too,” Jordan reportedly said.

The superstar athlete as a neutral avatar of corporate America persisted well into the new century. In 2007, Ira Newble, a no-name reserve for the Cleveland Cavaliers, asked his teammates to sign a letter condemning China’s involvement in the genocide in Darfur. All but three casually signed on to oppose the slaughter, but one of the abstainers was a 22-year-old LeBron James, already well on his way to becoming America’s most famous athlete. “It’s basically not having enough information,” James explained, though Newble and others speculated it may have had something to do with James’s Nike relationship and the company’s ties to China.

Which makes it all the more surprising that, five years later, James helped launch the modern athlete-as-activist movement. On February 26, 2012, Trayvon Martin was getting ready to watch James, Dwyane Wade, and Chris Bosh, the three best players from his favorite team, the Miami Heat, play in the NBA All-Star Game, when he put on a hoodie to go buy some Skittles. Martin’s killing took place just 20 miles from the game, but even as the story grew, reporters covering the team didn’t consider bringing it up with James. “We didn’t ask him about the issues of the day,” said Brian Windhorst, an ESPN reporter who has covered James throughout his career.

A few weeks later, Gabrielle Union, the actress who is now married to Wade, made a call to Michael Skolnik, who was working with Martin’s family. Union was seeking advice on how to draw attention to the issue, and they began talking about getting James and Wade involved. (Many male athletes seem to have been coaxed down the road to wokeness by the women in their lives.) “I was like, ‘Whatever you can get them to do: Write his name on their shoes, take a selfie’ — although I don’t think selfie was a term at the time — ‘that would mean the world,’ ” Skolnik said. Union took the ideas to Wade, who talked with James about what to do. On a road trip in Detroit, James and Wade gathered their teammates and persuaded them to pose for a photo with their official Miami Heat hoodies up, as Martin’s had been. James posted the picture to Twitter, and suddenly Trayvon Martin wasn’t just the top story on MSNBC but on ESPN, too: Windhorst, who was living in Florida, said he had never even heard Martin’s name before James posted the photo.

“That picture was John Carlos and Tommie Smith for our generation,” Skolnik told me recently from his office in Brooklyn. (He now runs a branding agency that puts on social-impact campaigns, but his bona fides were burnished by seven years as political director for Russell Simmons.) In 2012, the Black Lives Matter movement had not yet formed, there was little recent precedent for athletes’ speaking out, and players had no idea how their teams, or the league, might respond. Smith and Carlos, for instance, had become pariahs after the Olympics. At the time, the only other controversial social issue with even limited traction in the sports world was marriage equality. Hudson Taylor, who runs Athlete Ally, which advocates for LGBTQ rights in sports, told me that just two years ago he was talking to a prominent NBA player who said he was in favor of marriage equality, but that he was Christian and worried about losing fans. Brendon Ayanbadejo, a Baltimore Raven, was one of three NFL players who spoke out in support of gay marriage, but his campaign received limited attention, positive or negative, until 2012, when a Maryland state senator wrote to the Ravens requesting that the team “inhibit such expressions from your employee.” The story caused an uproar, stoked by an article Minnesota Vikings punter Chris Kluwe wrote, for Deadspin, in which he memorably assured the senator that married gay couples “won’t magically turn you into a lustful cockmonster.” Less than a year later, Jason Collins became the first openly gay player in any major American professional sport.

But Trayvon Martin’s death was a particularly galvanizing moment for black athletes, and other NBA players followed the Miami Heat’s lead, posting similar photos or arriving at games wearing hoodies. Skolnik recalled bringing Sybrina Fulton, Martin’s mother, to the Knicks locker room at Carmelo Anthony’s request. Anthony was initially speechless in front of Fulton and gave her a jersey that he had signed I AM TRAYVON. Fulton burst into tears. “She said, ‘Why do they care about me?’ ” Skolnik said. “She just couldn’t grasp the idea that these famous athletes were so touched by her.”

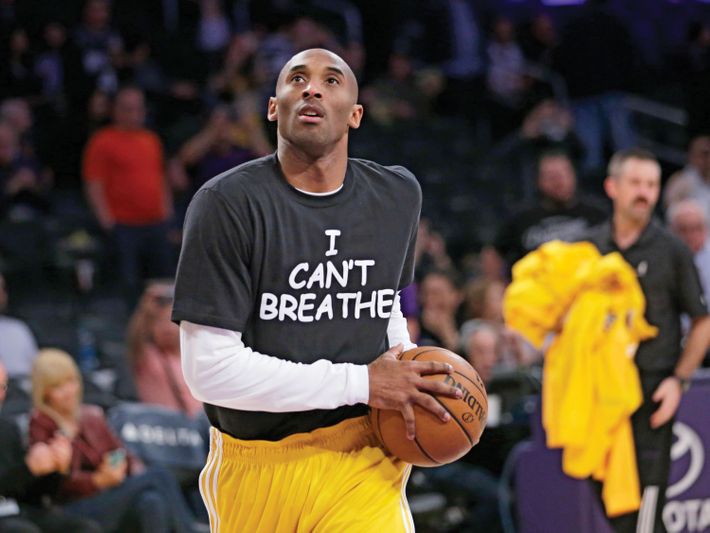

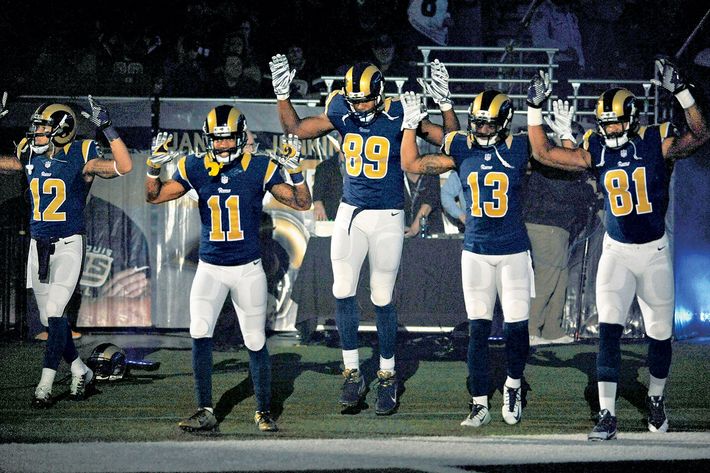

The years after Martin’s death found athletes speaking out with increasing regularity. In 2014, after TMZ posted audio of Donald Sterling, the owner of the Los Angeles Clippers, making wildly racist remarks, James quickly declared, “There’s no room for Donald Sterling in the NBA,” and Clippers players wore their warm-up shirts inside out, hiding the team logo, before their next game. Two days later, the league banned Sterling for life. That November, five St. Louis Rams walked onto the field holding their hands in the air, to honor Michael Brown, who had been killed in Ferguson, and after Eric Garner’s death in Staten Island, a number of NBA players wore shirts that read I CAN’T BREATHE onto the court, including James and members of the Brooklyn Nets. The shirts should have drawn a fine for violating the league’s dress code, but NBA commissioner Adam Silver decided against levying penalties.

Social media allowed players to share their concerns with the public instantly and easily. It also meant they were sitting in locker rooms together watching videos of young black men being killed, leading many to wonder, despite their personal success, how much better things had gotten for black people in America. “The only reason Mike Brown, who was seen as a big hulking black man, was dead in the street, as opposed to LeBron James, who is a big hulking black man, was that LeBron James was not there,” Edwards said.

It also helped that a (relatively) young black sports obsessive was in the White House. President Obama saw athletes not only as friends but as potential allies, and when he took office, he revamped the Office of Public Engagement and Intergovernmental Affairs with liaisons to dozens of different constituencies, including the obvious ones — the LGBTQ community, Christians, Native Americans — but also to the sports world. The White House maintained a roster of players, like NBA stars Chris Paul and Grant Hill, who could be counted on to join various campaigns. (“It closely correlated to who golfed with the president,” one former staff member said.) NBA teams in town to play the Washington Wizards asked for White House tours, which the administration tried to turn into recruiting events: When the Detroit Pistons visited last year, for instance, the president met with them in the Roosevelt Room to solicit their support for his My Brother’s Keeper mentoring initiative. Other athletes used their face time with the president to push their own causes, and when James and the Cavaliers celebrated their 2016 championship at the White House in November, they talked about police brutality with Obama behind closed doors. Some players even reached out on their own: Kobe Bryant regularly texted ideas for various campaigns to White House staff members.

At first, the White House mobilized athletes primarily for uncontroversial causes, like the First Lady’s “Let’s Move” fitness campaign, but as players began to demonstrate an increasing outspokenness during Obama’s second term, the administration started asking for support on more controversial topics. “Health care was the first one where athletes actually said no,” Kyle Lierman, who led outreach to the sports world for the White House from 2010 to 2014, said. “It was initially like pulling teeth.” As the White House desperately tried to hit its health-care enrollment goals, President Obama made a rare personal call to James, asking him to lend his voice to the campaign; a member of James’s management team said that while James supported the ACA, Obama’s personal request was the reason he agreed to help. “Once LeBron came out for us, it created the space for other athletes to jump in,” Lierman said. The following week, he sent an email to a number of prominent athletes, highlighting James’s PSA, and dozens wrote back offering to help. Eventually, the administration began using sports stars as advocates who, unlike Hollywood celebrities, were mostly able to sidestep charges of elitism and more directly communicate with specific regions. In 2015, Milwaukee boosted its ACA enrollment more than any of the 19 other cities targeted by the White House, which the administration credited in large part to the fact that a number of players from the Bucks, the local NBA team, had been persuaded to support the initiative.

Speaking out had now become almost an obligation. In 2015, after a grand jury declined to indict two Cleveland police officers involved in the death of Tamir Rice, activists launched a “No Justice, No LeBron” campaign, urging James to protest by refusing to play. But when James was asked about the campaign, he replied, “To be honest, I haven’t really been on top of this issue, so it’s hard for me to comment.” It was meant as a responsible reply to a complex situation, but some fans were disappointed, and the same reporters who hadn’t thought to ask James about Trayvon Martin’s death were now surprised that he would be unaware of a political issue roiling his city. One of James’s confidants says that, today, whenever James sees a piece of news that interests him, he notifies an assistant, who will respond with four or five articles for him to read on the topic.

Other athletes who wanted to speak out, but were wary because they found themselves unprepared to do so, went looking for ways to become better informed. Last July, Wade Davis, a former NFL cornerback who has become a full-time activist — “I’m an intersectional feminist,” he told me, citing bell hooks as an inspiration — was able to recruit 35 NFL, NBA, WNBA, and professional soccer players to attend a seminar in a Los Angeles apartment (several called in by Skype) led by two leaders of the Black Lives Matter movement, who explained how a variety of forces, from housing policies to gender to a lack of economic opportunity, were just as important to understand as police brutality. Every politically active athlete I spoke with told me the last thing they wanted was their lesser-informed teammates speaking up just because they thought they had something to say. “To be quite honest with you, I know a lot of athletes who, I’m glad they’re quiet, because they haven’t done their homework,” Harry Edwards said.

Aside from the Sterling incident, it had been hard to get athletes to act collectively. But last summer, after the deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile within a day of each other, Carmelo Anthony decided it was time. “I’m calling for all my fellow ATHLETES to step up and take charge,” Anthony said on Instagram, posting a photo of a press conference from 1967 at which Bill Russell, Jim Brown, and Lew Alcindor, who later changed his name to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, joined Muhammad Ali to express their support for Ali’s objection to being drafted during the Vietnam War. In 2014, William Rhoden, then a New York Times sportswriter, called that press conference “the first — and last — time that so many African-American athletes at that level came together to support a controversial cause.”

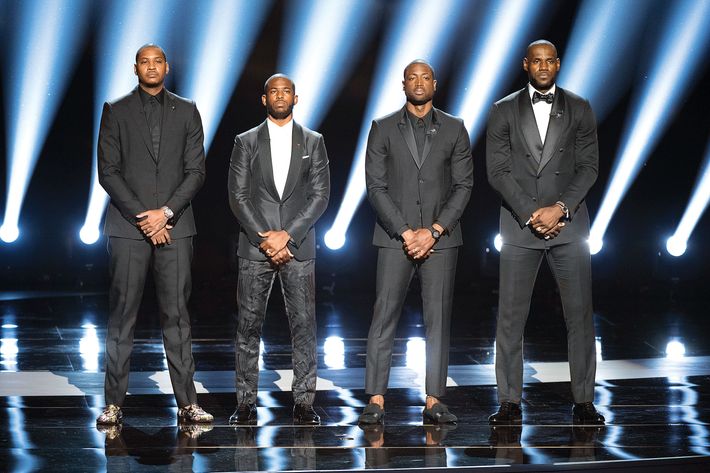

Anthony has a regular group text with James, Wade, and Paul, and the quartet spent the following weekend coming up with a plan. They were scheduled to attend the Espys, ESPN’s annual awards show, the following week, and a member of James’s team told ESPN the players wanted to make a joint statement at the top of the broadcast. The four players spoke to an Espys writer who helped distill their group text into a forceful call to action, which they read together onstage. “As athletes, it’s on us to challenge each other,” Wade said. “The conversation cannot stop as our schedules get busy again … It won’t always be comfortable. But it is necessary.”

The impact was swift. Two days after the speech, Nike’s CEO put out a statement explicitly supporting Black Lives Matter and citing the appearance by James, Anthony, and Paul as an instigating factor. (He left out Wade, who isn’t a Nike athlete.) A week later, Michael Jordan announced that he would be donating $1 million to both the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and the Institute for Community-Police Relations, a law-enforcement advocacy organization whose head was so surprised by the donation that he called to make sure it had come from that Michael Jordan. “I know this country is better than that,” Jordan said of the recent killings. “I can no longer stay silent.”

But Kaepernick’s statement, six weeks later, rang out louder than anything from the NBA, despite the fact that he was far from the first athlete to protest the national anthem. “I cannot stand and sing the anthem,” Jackie Robinson wrote, in 1972. “I know that I am a black man in a white world.” Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf, a guard for the Denver Nuggets, was suspended by the NBA in 1996 for refusing to stand during the song, and David West, a forward for the Golden State Warriors, recently told the Undefeated, ESPN’s new website covering the intersection of race and sports, that he has stood two feet behind his teammates during “The Star Spangled Banner” for so long that he has forgotten when he first started doing it.

Kaepernick, however, was the first player to bring such a protest to the National Football League, America’s modern pastime. The NFL has long been conservative, with a fan base that is overwhelmingly white — African-Americans, Hispanics, and Asian-Americans all watch the NBA in higher percentages than whites — and has been far less receptive to its players’ involvement in activism. “The NFL doesn’t want you to talk about anything other than football,” says Chris Kluwe, who has claimed that he lost his job in part for being outspoken about marriage equality. Where NBA teams have a dozen players, all of whom more or less know one another’s (often similar) political beliefs, an NFL locker room has more than 50 players from a variety of backgrounds. While some NFL owners were supportive, the majority are conservative — even Shahid Khan, the Muslim-immigrant owner of the Jacksonville Jaguars, voted for Trump — and at least one reportedly insisted that his players stand for the anthem. One anonymous front-office executive called Kaepernick “a traitor.”

The NBA, meanwhile, has largely supported players’ protests, even on the court, and many coaches, most of whom are white, have recently been turning their press conferences into political lectures. A few days after the presidential election, Gregg Popovich of the San Antonio Spurs spoke for five minutes about his disappointment with the state of American politics, stopping a reporter who interrupted him to ask another question. “I’m not done,” Popovich said. “I’m sick to my stomach thinking about it.” Compare that to a press conference at which Bill Belichick, whose New England Patriots were preparing to play the Seattle Seahawks, briefly addressed the fact that Trump had recently read a laudatory letter from him at a rally, then deflected follow-ups:

Reporter: “Your team’s always been good at keeping outside distractions on the outside, given the nature of this presidential race …”

Belichick: “Seattle.”

“Did you find it — ”

“Seattle.”

Kaepernick’s disruption of America’s song, during America’s game, had opened him up to attacks. A Houston-area cigar lounge called the Man Cave started using his jersey as a doormat, and even Ruth Bader Ginsburg called Kaepernick’s protest “dumb and disrespectful,” before later apologizing. Kaepernick found plenty of outside support, as his jersey became the NFL’s top seller — he was fortunate to be in San Francisco rather than a more conservative NFL city — and several teammates joined his protest. (Kaepernick began taking a knee rather than sitting, as he had initially, on the advice of a retired football player and military veteran, who felt it seemed more respectful.) But only 50 or so of the league’s 1,700 players took knees or raised fists alongside him. Several teams made unified statements of solidarity, but no white NFL player joined Kaepernick, and Megan Rapinoe, of the U.S. women’s soccer team, was the only white athlete from any major professional sport to take a knee. The rest of the NFL either disagreed with Kaepernick’s message or with his methods, or feared the consequences. Brandon Marshall, of the Denver Broncos, lost several endorsements for kneeling, and other players admitted the stress was difficult to bear. “I had a conversation with a player who knelt with Colin during week one, and he calls me and says, ‘How many weeks do I have to kneel?’ ” Skolnik said. “I was like, ‘You gotta go the distance, buddy. You’re not gonna get up soon.’ ”

But even with limited participation, Kaepernick’s protest had opened the debate over policing and race relations to a wider audience. “I was kind of dumbfounded, to be honest with you,” Anquan Boldin, a veteran wide receiver for the Detroit Lions, told me about the outcry over Kaepernick’s protest. Boldin had been speaking out on policing for nearly a year, ever since his cousin was shot and killed by a plainclothes officer, but he had struggled to find an audience. “I can’t believe it takes somebody like Kaepernick to kneel during the national anthem for people to talk about a problem that has been going on for years,” Boldin said.

Boldin didn’t take a knee, but the example of Kaepernick’s protest made room for athletes to get involved in a variety of ways. During the season, Boldin started a group text that grew to include more than 80 players, all of whom wanted to do something but had no idea what or how. “I don’t think guys know where to start,” Boldin said. “It’s one thing to do work in your community, but it’s another thing to set up meetings with Capitol Hill.” In 2013, Boldin went to Senegal with Oxfam, which had spent years lobbying Congress to hold a hearing on mining issues in West Africa with no success. He offered to visit D.C. to drum up support for a hearing, and within two weeks, it was on the schedule. “It was a wake-up moment for me in terms of understanding the power we have,” Boldin said.

Boldin wanted to go back to Capitol Hill to talk about policing, so he turned to Andrew Blejwas, a political-communications specialist who had organized the Oxfam trip. Boldin recruited four other players, including Josh McCown, a white quarterback, and Malcolm Jenkins, of the Philadelphia Eagles, who had raised a fist with Kaepernick. Blejwas set up meetings in November with four different congressional offices, the Congressional Black Caucus, and, with the help of the NFL Players Association, the White House.

The players were quick political studies. “First off, these guys are brilliant — learning plays is not easy,” Blejwas said. “They synthesized the ideas that we were talking about much better than we did.” Boldin and the others also knew why they had been granted an audience, and how to play the game, with long-term gains in mind. After one congressman spent most of their visit talking about a bipartisan softball game he coached, the players signed a softball and mailed it to him; when progressives criticized them online after they posed for a picture with Paul Ryan, who emerged for the photo op after leaving the actual meeting to his staff, the players brushed it off. “Don’t think these guys don’t know what’s going on,” Blejwas said. “They know they have to get that next meeting.” Boldin’s group is currently planning a return trip to D.C. in March, with more players, in the hope of presenting testimony to the House Judiciary Committee on criminal-justice reform. (Lierman, the former White House liaison, as well as two former State Department officials, is launching a separate consultancy to accommodate the growing number of athletes who want to get more involved in the political process.) The most difficult thing, Blejwas had found, was getting people in D.C. to realize that Boldin and the others were capable of doing serious work. Before Boldin’s first appearance to give testimony in D.C., one person involved in setting up the hearing asked Blejwas, “Do you know if Anquan … can he read?”

“An NFL player can help achieve all these important objectives, and people will still be like, ‘Why don’t you just do a PSA?’ ” Blejwas told me. “It’s like, ‘No, we’re trying to do work. We’re not trying to get on TV.’ You can really move the needle if you just trust that this 32-year-old black man can read.”

Of course, professional athletes have only so much direct electoral power. An ESPN survey found they favored Hillary Clinton by nearly two to one. (Kaepernick didn’t vote.) Persuading athletes to publicly get behind a candidate can sometimes be more difficult than getting them to back a cause: Michelle Kwan, the former figure skater, who did surrogate outreach for Clinton’s campaign, said a number of Olympians told her that they supported Clinton but that their endorsement deals, which they rely on more than basketball or football players, prevented them from saying so. She helped persuade Chris Paul to tweet that he was With Her, and LeBron James wrote an endorsement in an Ohio newspaper two days after his boss, the Cavs’ owner Dan Gilbert, hosted a Trump fund-raiser. James also stood next to Clinton at a rally in Cleveland during the campaign’s final week. “I was one of those kids and was around a community that was like, ‘Our vote doesn’t matter,’ ” James said, explaining his own political transformation. “But it really does. ”

But even the most popular man in Ohio couldn’t deliver his home state, and the sports world is unlikely to embrace the Trump White House as it did Obama’s. “If you think any NBA team will show up at the White House for a photo op with Trump, you’re crazy,” Edwards said. Trump has shown little interest in sports beyond his own golf courses and inviting the Patriots’ owner to dine with the Japanese prime minister at Mar-a-Lago. (As one indicator of how White House outreach might look different, a person briefed on the hiring process said the administration was considering Andrew Giuliani, Rudy’s son and a former minor-league professional golfer, as its sports liaison.) Shortly after Trump’s victory, LeBron told his wife, “I think we’re going to have to do more,” according to Sports Illustrated. A number of people suggested to me that Trump’s policies might, in fact, awaken even the sleepier parts of the sports world, like Major League Baseball, none of whose players joined Kaepernick’s protest but nearly a third of whom are Hispanic and might be inspired to speak up if Trump continues to pursue a border wall or other aggressive immigration restrictions. (Adrian Gonzalez, a Mexican-American player for the Los Angeles Dodgers, refused to stay at a Trump-branded hotel last season.) The newly established sense that athletes can, and should, use their cultural cachet to promote political change seems to have emboldened others to speak out on subjects that hew less closely to their own identity politics. Days after Trump’s inauguration, Kaepernick tweeted his support for protesters at Standing Rock and his opposition to abortion restrictions, and earlier this month, several NFL players backed out of a government-sponsored trip to Israel after pressure from activists who argued it was likely to present a skewed view of the Palestinian situation. Two members of the Detroit Lions showed up at the Women’s March on Washington in January (while James gave the protest a shout-out on Twitter), and this past weekend’s NBA All-Star Game was moved from Charlotte to New Orleans in protest over the state’s discriminatory bathroom law, a switch supported by Stephen Curry and Chris Paul, both North Carolina natives. “Some things are bigger than the game,” Paul said.

What has emerged is a generation not only willing to shine a light on injustice but prepared to make concrete demands. “Carmelo and Steph are fantastic examples of guys who can really be a huge loss to a brand by walking away,” said Sherrie Deans, an executive with the National Basketball Players Association. “But even guys who can’t do that are saying, ‘If you’re gonna be a brand partner of mine, I need you to acknowledge the totality of who I am.’ ” Brands seem to want to be on the right side of history, too, and social responsibility has become a central part of many athletes’ self-presentation: When James posed for a Sports Illustrated cover naming him the magazine’s 2016 Sportsman of the Year, he wore a safety pin as a signal of his allyship.

But as athletes begin to recognize their control over the means of production, and to demonstrate a willingness to act collectively, the next phase of their activism may most closely resemble what happened in 2015 at the University of Missouri. After a series of racist events on campus, to which administrators had responded slowly, the football team declared it wouldn’t play an upcoming game unless the university president resigned. “I had been taking a sports-management class that semester, and I learned how much money we make the university,” Ian Simon, one of the protest’s leaders, told me recently. Regular students had been protesting for weeks to no avail, but after the football team got involved, the president was gone within 48 hours.

Kaepernick, for his part, was spending February announcing more donations, including one to a group in Brooklyn that helps homeless veterans, and tweeting out daily Black History Month lessons. The quarterback may become a free agent next month, and it remains to be seen which teams might be interested in signing him. He spent one of his rare off days last season taking the GRE.

Even if Kaepernick never plays again, he’s already done enough for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture to acquire his jersey and cleats. “Kaepernick took the bullets,” Wade Davis, the cornerback turned activist, told me. “He is the Muhammad Ali of this era. He took some hits from a shotgun, so the next guy will take bullets from a .22, and the next guy gets hit with a sling.” But even if he devotes himself to full-time activism, Kaepernick’s reach will never be as great as it has been as an NFL quarterback. Simon, from the University of Missouri, went to last year’s Espys, where James, Wade, Anthony, and Paul spoke, but he was passed over in the NFL draft. He isn’t sure how the protest affected his status, but he said that every team asked him about it, and when I talked to him earlier this month, he was settling into a new job at the front desk of a family medical practice in Texas. There were many issues Simon wanted to speak on, but it was harder to get an audience. “I think about that a lot,” Simon said. “You can stand on the corner and preach all day. But if your message can’t reach the right people, it’s just words in the wind.”

*This article appears in the February 20, 2017, issue of New York Magazine. It has been updated since its original publication.