The United States is poised to impose tariffs on $34 billion worth of Chinese goods at midnight, and Beijing is prepared to respond in kind.

But American companies won’t need to wait for Chinese retaliation to feel the sting of Donald Trump’s trade war — because some of the president’s own tariffs will actually fall on American firms.

Or so Xi Jinping’s government says.

“The U.S. is firing shots to the world, including to itself,” Gao Feng, a spokesperson for China’s Commerce Ministry, told reporters Thursday. Gao claims that $20 billion of Trump’s $34 billion tariffs will fall on foreign companies that operate within China and export to the U.S. market — including multiple American firms.

That might strike the president as more feature than bug of his trade policy; Trump has evinced no great affection for American companies that export to the U.S. market from overseas. Still, Beijing’s promised retaliation to U.S. tariffs will be sure to hurt plenty of our nation’s domestic exporters. China’s reciprocal duties will target 545 U.S. products worth about $34 billion, including soybeans, whiskey, orange juice, electric cars, salmon, and cigars. Soybean farmers — who are already reeling from the uncertainty surrounding NAFTA renegotiations — will be hit especially hard, as China is expected to cancel most of the remaining soybeans they had committed to buying from the U.S. in the year ending August 31, according to Bloomberg.

The U.S. plans to implement tariffs on another $16 billion of Chinese goods later this year. And the president has also threatened to retaliate against China for its proposed retaliation, vowing to place a 10 percent tariff on an additional $200 billion of Chinese goods, should Beijing go forward with its promised tariffs tomorrow. And if Xi Jinping’s government takes punitive action in response to that extra $200 billion in tariffs, the Trump administration has pledged to enact another $200 billion in duties.

The president has suggested that the U.S. would have an inherent advantage in such an escalating conflict. After all, since China only imports $130.4 billion worth of U.S. products, it cannot mount a reciprocal response to $450 billion worth of tariffs on its goods.

But just because Beijing can’t retaliate reciprocally doesn’t mean it can’t hit back proportionately: China can still devalue its currency (to disadvantage American exporters), disrupt U.S. supply chains by freezing activities at select ports, or decline to approve acquisitions sought by American companies.

On Thursday, Gao tried to reassure investors that it would not take such punitive actions against American companies within its borders.

“As for possible impacts on businesses from the trade war initiated by the United States, we will keep assessing the situation and make efforts to help [foreign] businesses to mitigate any possible impacts,” Gao said. “In the past few decades, China has always been one of the most popular markets for foreign investors. It is not only because of China’s large market size, but it is also because the Chinese market is stable, rational and committed to the rule of law.”

But some American firms in China believe that they’re already bearing the brunt of Beijing’s displeasure with the White House. As the Washington Post reports:

An American company that ships cherries to a coastal province in southeast China recently encountered a new hurdle at the border: Customs officers ordered a load into quarantine for a week, so it spoiled and was sent back to the United States.

American pet-food makers, meanwhile, say they’re facing more rigorous inspections at ports, which delay goods from reaching shelves and ultimately hurt sales.

And a U.S. manufacturer that exports vehicles to China recorded a 98 percent jump in random border inspections over the past month, throwing the firm behind schedule.

American business leaders fear these are the “qualitative measures” China warned it would unleash if President Trump imposed tariffs on its exports to the United States.

Investors are struggling to calculate the odds that Washington and Beijing will stick to the hard lines they’ve drawn — as opposed to seeking some mutually face-saving compromise that averts prolonged trade war.

On the one hand, unlike so many of Trump’s other trade spats, his standoff with China (arguably) has real stakes for both nations. The official justification for America’s tariffs is to deter Chinese theft of American intellectual property. And by most accounts, Beijing has made a routine practice of such thievery — as part of its broader “Made in China 2025” project, which aims to position China as a dominant force in the high-tech industries of the future. Which is to say: Beijing is using violations of international trade rules in a bid to reshape the global economy in a manner that will weaken the West relative to China. This is the kind of conflict between an incumbent hegemon and rising challenger that produced shooting wars in previous eras of human history; it wouldn’t be shocking if it produced a mutually destructive economic war in our epoch.

On the other hand, the same force that makes an actual war between China and the U.S. unlikely — the profound interdependence of their national economies — also reduces the likelihood of an extended trade war.

In its first round of tariffs, the White House targeted advanced industrial inputs and technology; which is to say, imports that aren’t sold directly to consumers. But there is no way to impose tariffs on $250 billion (let alone $450 billion) worth of Chinese products without drastically increasing retail prices for American consumers. As is, inflation is already nullifying real wage growth for most American workers. With midterm elections approaching, it’s far from clear that Trump is prepared to weather rising prices, angry U.S. exporters, and growing opposition among his own party’s elected officials and donors. On other issues, the president has shown little inclination to put (his conception of) America’s long-term interests above his own short-term political gain. It is not hard to imagine him declaring victory, after securing an agreement that does not actually address his substantive complaints (after all, that is precisely what he just did in negotiations with North Korea).

Meanwhile, China has its own reasons for seeking a resolution sooner rather than later. The nation’s stocks have entered a bear market in recent weeks amid fears of the looming trade war. If the skirmish ends with each side imposing $50 billion worth of tariffs, China would lose 0.2 percentage points of growth in 2019, according to Bloomberg Economics; if the trade war escalated further, it could lose up to half a percentage point.

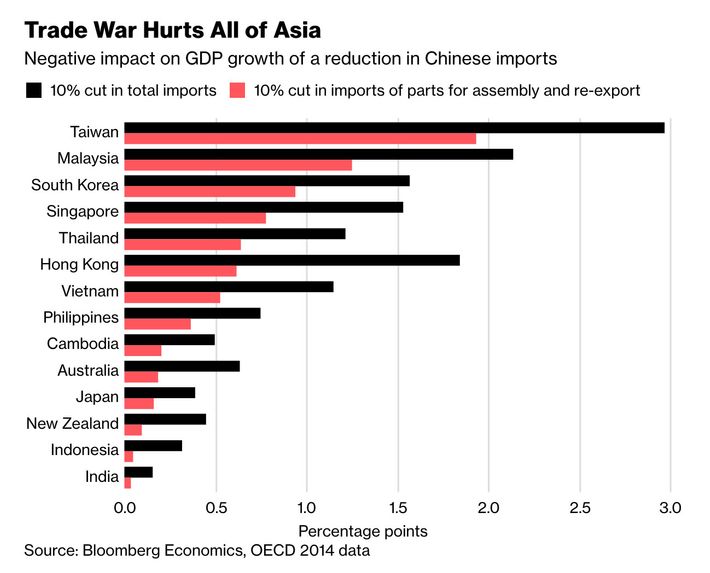

And both sides are likely to hear pleas for normalized trade relations from their respective allies and economic partners. Many Asian nations supply Chinese firms with inputs that are then used to make goods shipped to the United States. For this reason, Taiwan, Malaysia, and South Korea all actually have more to lose from a steep drop in Chinese imports than even China itself.

For the moment though, there are few signs that president Trump has any ambivalence about pressing ahead with a worldwide trade war, even in the face of high (economic) casualties. In fact, the White House is preparing to open up a new front in that conflict, by imposing duties on European automobiles.