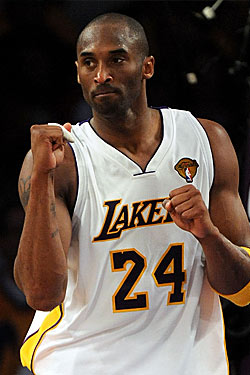

Today on Slate, writer Alan Siegel asks whether Kobe Bryant is actually a clutch shooter. Citing studies by economists David Berri and Dan Ariely, he concludes that Kobe does not actually have “a unique ability to score in the clutch.” The reasoning goes that Bryant gets a good rep simply by taking a lot of late-game shots — so even though he makes a lower percentage of them than players like, say, Andrea Bargnani, he makes more in total, giving our bias-ridden monkey brains the false impression that he’s better simply because we end up seeing him more times on highlight shows.

The problems with this analysis start with Siegel’s comparison of late-game basketball scoring to clutch hitting in baseball. It might seem reasonable: Taking the last shot of a basketball game is that sport’s closest analogue to batting with two outs in the ninth. But while everyone on a baseball team has to bat when their spot comes up, basketball teams have to pick one person to take a late-game shot, which makes apples-to-apples comparisons between players much more difficult. Bryant-like slashers get “stuck” with primary ball-handling duty at the end of games because defenders almost exclusively play a high-pressure man-to-man style; five guys stuck like glue to their man makes passing almost impossible. As any basketball color analyst will tell you, ball movement is the key to any organized offensive system. But you can’t go out and run a motion offense in the last fifteen seconds of a basketball game and expect it to work. The defense is overplaying the ball and overplaying the passing lanes for the very reason that they don’t want you to run a well-coordinated team offense. So you deploy counter-moves, trying to use the defenders’ close positioning against them. If you have the ball, a defender up in your grill is good at keeping you from passing and shooting jumpers, but bad at keeping you from making a sudden move and slipping past them — and off the ball, pressure D can keep you from receiving the swing or entry passes essential to an offensive system, but opens up the possibility of quick backdoor cuts to the basket.

The best kind of offensive player to have at the end of the game, then, is one who can take the ball and get by a defender one-on-one. But Siegel’s sources don’t acknowledge that being in a position to even take a late-game shot is a skill. They look at Bryant’s low clutch shooting percentage relative to someone like Andrea Bargnani and say that Bryant is overrated, because they’re only looking for efficiency. Ariely actually says that if a basketball player changes his game to take more shots and makes the same percentage of them he has previously, he’s demonstrating “no improvement in skill.” That’s not correct: The winner of a basketball game isn’t determined by shooting percentage. A team must shoot the ball frequently or it will literally be taken away from them by the referees. Berri and Ariely ignore the fact that basketball has time limits; by their standard, a player who takes an endgame shot and misses is doing worse than a player who fails to take a shot at all and lets time run out!

In other words, comparing Kobe Bryant’s late-game efficiency to Andrea Bargnani’s only makes sense if you hand them each the ball an equal number of times in a clutch situation and then see who ends up winning more games. But that doesn’t happen because of factors that don’t get incorporated into efficiency data. Bargnani’s coach doesn’t give him the ball in the clutch as much as Kobe’s coach because he believes Bargnani isn’t as effective a scorer. His teammates don’t pass to him in those situations as often as Kobe’s teammates for the same reason. And Bargnani himself likely defers to teammates more in the clutch because he’s not as skilled as Kobe at finding an open shot.

With this all said: Kobe Bryant certainly might not be the best clutch player in the NBA. Siegel’s article quotes economist Wayne Winston making a convincing case for giving LeBron James that title, and one imagines James, on the Cavs, has as much if not more responsibility than Bryant does on the Lakers for creating late-game shots, making the comparison more sensible. Meanwhile, basketball stat-heads are working on trying to incorporate the basic need for shot creation into efficiency statistics, which might indeed conclude that Bryant ball-hogs too much compared to his peers. It’s a young field, to be sure. But Berri and Ariely aren’t taking it in the right direction.