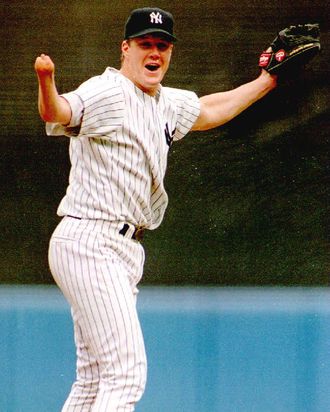

Jim Abbott pitched in parts of ten major-league seasons, including two as a member of the Yankees. Abbott, who was born without a right hand, would win 87 big-league games in his career, and on September 4, 1993, he threw a no-hitter against the Cleveland Indians at Yankee Stadium. His new memoir, Imperfect, co-written with Tim Brown, is in stores now. Abbott spoke with The Sports Section about his no-hitter, life after baseball, and signing an autograph for Fidel Castro.

At what point did you begin to think that you might be able to play baseball professionally?

Well, that came in stages. I was drafted out of high school, but somehow that just seemed so far off that it didn’t really seem like a realistic opportunity at that point. It wasn’t really until I played on the Olympic team after my junior year — or actually, after my sophomore year, when I played on the Pan-Am team, playing with some of the best college players around the country. And I knew that they were going to have the opportunity, and I knew that I was competing with them and doing well with them. And you know, I hoped that I would get that same shot.

In the book, you talk about how you don’t want be known simply as “Jim Abbott, the one-handed baseball player.” As you go through this book tour, you’re probably answering a lot of questions about your disability. Is that uncomfortable, even now? Or is it different since you’re telling your story your way?

Well, that is a good observation. The reason I’m glad I wrote it now instead of twenty years ago is that I’m able to talk about that in a more open way. I used baseball to sort of try to move past the label, and I think we all do. I don’t think any of us want to be labeled or have a preconceived notion of what we can and can’t do before we even are allowed the opportunity. So that’s what I railed against, and that’s what I didn’t really like, and that’s what baseball helped me to fight back against. But as I got older, even within my major-league career, I grew to understand that my hand was a big part of who I am. And in a lot of ways, it pushed me to places that I don’t know that I would have gone without it. And so, in those ways, I came to appreciate, if not fully appreciate, being born the way I was, appreciate the places that it pushed me to, and the experiences that allowed me to have.

One of the more uncomfortable things to read were the parts about people potentially trying to profit off your disability: somebody trying to sell you back what he claimed was your prosthetic arm, or the idea that someone would want your autograph on a baseball with Pete Gray [who played in the majors despite losing an arm in a childhood accident], perhaps with an eye on selling it. Was that sort of thing especially hard on you?

Yeah. Well, the gentleman who tracked me down and tried to sell my quote-unquote arm back, that was particularly crass. (Laughs.) But you know, when people tried to have a piece of memorabilia with just Pete Gray and my name on it, I didn’t feel comfortable with that. You know, I felt somehow that maybe it lumped us together in ways that were only physical. And I don’t know if he would have appreciated that, and I didn’t think it was right. And there did seem to be some sort of profit motive to it, you know, that it made the ball all the more unique, more valuable, so I just tried to politely refuse.

Is your no-hitter even more impressive to you in hindsight when you look at the careers some of those Indians — like Jim Thome and Manny Ramirez — went on to have?

That was a heck of a lineup. Up and down, they were really an up-and-coming team. And Manny had just been called up, so to put him in the category he ultimately ended up being in is probably not fair. But he was certainly a threat, and Thome was a threat. And Albert Belle — people forget how good Albert Belle was at that point. And Carlos Baerga was one of the best hitters in the American League. Kenny Lofton was as dangerous as any lead-off hitter in the American League. All I have to do is think back to the game before (Editor’s note: when Cleveland scored seven earned runs off him in three and two-thirds innings) to think about what an impressive lineup that was. And I do appreciate it. It makes it special, knowing that it came against a really good hitting team like that. And it makes it special having happened in Yankee Stadium as well.

You played a few different sports growing up, either in organized leagues or with friends. It seemed like you didn’t have a passion for football but did have one for basketball. When you were, say, entering high school, was basketball your primary sports interest? Did you just turn to baseball because of circumstance when you didn’t make your school’s basketball team?

That’s exactly right. I loved basketball. Flint was a basketball town, and we had some really good players come out of there. And people went to the high school basketball games, and those guys were kind of like local heroes. And that’s what my friends and I did. Almost all of us had hoops on our garages. But baseball became my favorite, and you described it well: Sort of out of circumstance, you know — it was the sport I seemed to be best at. And ultimately, I started devoting all my energy to it. Flint will always be a basketball town, and I think most boys that grow up there, they love playing.

Would it have been more difficult to continue your basketball career, given your disability? Was baseball a better fit?

Yeah, I think so. That’s what I love about the game of baseball. [Like I say] when I speak to little leagues, people of almost any ability can play baseball. And they can contribute to a baseball team, whether it’s fielding, or hitting, or speed, or pitching, or leadership — whatever it is, you can contribute. So a person like me, missing a hand — there was a place on the baseball field for that. There was a place for my abilities, and I’m incredibly thankful. Probably more so than on a basketball court, although Kevin Laue at Manhattan College is playing with one hand and doing an incredible job. I’m a big fan of his, but he’s a little taller than I am.

You played for the United States at the 1988 Olympics, but this summer, baseball won’t be a part of the London Games, even as a demonstration sport. What are your thoughts on baseball being eliminated from the Olympics?

Well it’s a bummer. That was probably the greatest team memory and experience I ever had, playing with those guys. And I wish it was an Olympic sport, and I wish it was still an amateur sport in the Olympics. Because when I played, a lot of us had signed contracts, but you didn’t take any money, and you had to be an amateur player. And so I was playing with Robin Ventura from Oklahoma State and Tino Martinez from Tampa. You just took so much pride in playing with these guys, and we really were able to compete against some of the best amateur teams in the world. You know, with the right coaching, and the right schedule, we really came together. So to see that lost, I’m bummed about that. I think baseball was a great addition to the Olympics, and an added note: I’m even more bummed to see softball not included. My own daughters played softball for a while. They don’t now, but it just gave young girls such a goal to shoot for, and I thought it was a great Olympic sport. It broke my heart more to see softball taken out than baseball.

You played games in Cuba with the U.S. team, and at one point in the book, you mention that Fidel Castro would later request an autographed baseball from you. Did you sign one for him?

I did sign it for him, through the Angels organization, and it was sent back. And I don’t know if he ever received it. I never heard anything more about it after that. That was an incredible experience to go down to Cuba and play in a stadium that had ten times as many people as any of us had ever played in front of. And the passion and the excitement — it’s almost indescribable the passion that Cuban fans feel for the game of baseball. It was unlike anything I had ever seen up to that point. I looked at signing the ball and sending it back as a token of appreciation of what baseball meant to the Cuban people and what that series meant to us, to go down there and play.

Is it bizarre to think that Fidel Castro might have an autographed baseball of yours on his mantel?

[Laughs.] It’s very bizarre. I wonder if there’s some treasure trove of things, and maybe it’s in there somewhere. [Laughs.] He certainly loved the game, and they had some great players. That was before any of the guys were able to defect. They had the third baseman, Omar Linares, and he was our age, and he was the best player on the field, by far.

What are you up to these days?

Well, I’m very lucky. I get to do some speaking, some motivational speaking. I travel a few times a month. It’s become a rewarding offshoot of my playing career. I get the chance to travel around, and I speak to groups that are a long way from my home, a long way from where I grew up, and people who do things entirely different from what I ever did. The baseball stories seem to resonate, and the principles that I found important while playing seem to apply across a wide spectrum of things that people do. And coming back from an event where you spoke in front of several hundred, or even a couple thousand people, and you feel like you did a good job, you feel like you may have touched a few people — it’s incredibly rewarding. It’s not quite winning a major-league game, but it’s close.