Knicks fans have become very familiar with the concept of the offer sheet over the past week: Landry Fields agreed to sign one with Toronto, making it unlikely that he’ll return to the Knicks, while Jeremy Lin agreed to sign one with the Rockets, essentially determining how much the Knicks will pay him once they match the offer next week, when all these things can become official. But a hockey fan monitoring the NBA’s off-season might be confused by all of this: Offer sheets are extremely rare in the NHL, even though they’re perfectly legal. But why?

Last summer, an NHL.com article addressed this question, and it pointed to a quote from former Flyers GM Bobby Clarke, who signed Ryan Kesler to an offer sheet in 2006 that was matched by Vancouver:

“I think the difference is that in the past there were no restrictions on how much you can spend,” Clarke told CBC Sports’ website. “So it was sort of an unwritten rule that you didn’t sign any Group 2 players because the other team would match. In today’s (salary cap) world, you may not match. You may take the compensation. This is the first one (offer sheet), but it’s not going to be the last.”

But that’s not really how things have played out, though. Under the current collective bargaining agreement, which went into effect in 2005, there have been just six signed offer sheets (five of which have been matched). If there had been an unwritten rule that GMs shouldn’t extend offer sheets to restricted free agents, it would appear that it’s still in effect.

There are some theories out there as to why this is the case. Last July, Ryan Lambert of Puck Daddy presented a few possible reasons for the general lack of offer sheets. The biggest reason, he argued, is that there appears to be “a gentleman’s agreement that offer sheets are simply not a thing that’s done.” It makes sense: For something so perfectly legal and potentially useful to be used to infrequently suggests there’s an understanding among GMs to simply not use them. Indeed, some writers have suggested this sort of thing sounds, shall we say, a little collusion-y.

But Lambert also touches on what we think is key to all of this, which explains why the general managers — men whose goal is to assemble the best team they can — wouldn’t use offer sheets when it was appropriate: GMs might be afraid that, if they try and sign another team’s restricted free agents, other teams will target theirs. In the long run, an offer sheet might help them land the initial RFA, but it could cost them down the line. There’s not a ton of evidence that suggests this thing is actually happening — since the lockout, only one team (Vancouver) has signed an RFA to an offer sheet, and later had one of its own players signed to one — but it’s not a totally unfounded fear. After all, Kings GM Dean Lombardi once publicly threatened to target the RFAs of any team that targeted one of his.

Of course, all of this could just as easily apply to the NBA — GMs in that league could, in theory, have the same fears about their RFAs being targeted if they go after those of another team — but offer sheets are more common in the NBA. Perhaps it has something to do with the compensation picks an NHL team must give up if they sign a player to an offer sheet and it isn’t matched. Maybe it’s that there have been so few offer sheets that each one stands out a bit more, which could further annoy GMs who think like Lombardi. Or maybe it has to do with GMs being concerned about escalating salaries.

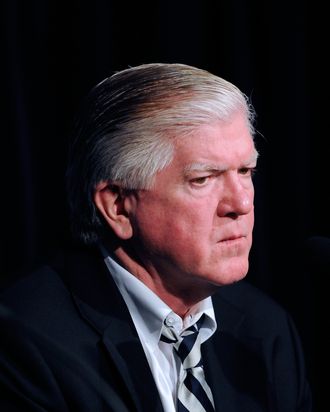

Remember the beef between Brian Burke and Kevin Lowe over Dustin Penner’s offer sheet, the one that reportedly had Burke willing to rent out an upstate New York barn to fight Lowe in? Burke explained at the time that his issue wasn’t with Lowe presenting Penner with the offer sheet, but with Lowe giving him such a huge raise over what he’d been making previously. Said Burke: “Edmonton has offered a mostly inflated salary for a player, and I think it’s an act of desperation for a general manager who is fighting to keep his job.” He explained further: “If you can identify a player and pay him appropriately and make him an offer, that’s fine. At some point, the deals you make, the offers you extend, whether the team matches it or not, impacts all 30 teams, including your own.”

Of course, the salary cap is designed to keep contracts from escalating indefinitely — overpaying a player impacts what a GM is able to do in assembling his roster elsewhere —but his point is that huge offer sheets that don’t necessarily reflect a player’s true value are bad for the game. In that NHL.com article, former Flames GM Craig Button (who says he doesn’t think teams are worried about retribution) wondered if huge offers to RFAs could impact the rates of a team’s future free agents. And Steve Yzerman has said that the reason he doesn’t like offer sheets is because they’ll always be matched unless a team “grossly” overpays the player, which is to say, they’re only useful if a team is willing to grossly overpay. (This is an excellent point, though it’s not like teams don’t overpay for UFAs sometimes if it means the difference between landing them and losing them.) Concerns over salary escalation precede this CBA: They came up, for instance, when the Rangers famously signed Joe Sakic to an offer sheet in 1997, only to see it matched by Colorado.

Offer sheets, in a lot of ways, are kind of mean. This isn’t to say that there’s anything wrong with them or that they’re immoral in any way, but their existence allows a team to steal away a player before he reaches unrestricted free agency by making things uncomfortable for the player’s original team, especially if that original team has salary-cap issues to deal with. (To go back to the NBA for a moment, the “poison pill” that the Knicks feared in Jeremy Lin’s offer sheet would only exist to make things harder on the Knicks.) The question, then, is this: Do NHL GMs avoid using offer sheets so as to not break some sort of gentleman’s agreement, thus pissing off other GMs and escalating salaries on top of it? Or is it because GMs are simply looking out for themselves and are worried not just about their salary-cap situation, but about potential retribution down the line? It could be a little bit of both, but this is sports, and as long as they’re playing within the rules, especially under a system that forces GMs to think about every dollar they spend, it’s hard to imagine those GMs are ultimately looking out for anyone but themselves. (Not that there’s anything wrong with that.)