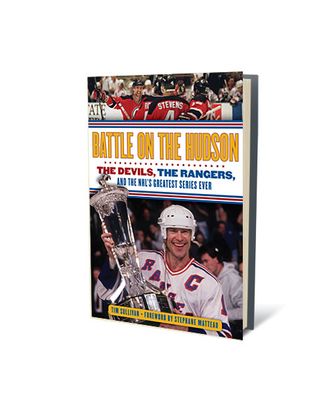

In Battle on the Hudson: The Devils, the Rangers, and the NHL’s Greatest Series Ever, Tim Sullivan chronicles the classic 1994 Eastern Conference Finals — the seven-game roller coaster of a series that featured, among other memorable performances, Mark Messier’s Game 6 hat trick and Stephane Matteau’s famous Game 7 double-overtime winner. The Sports Section spoke with Sullivan about what’s been forgotten about that series and why calling Matteau’s goal was so difficult for announcers.

Everyone probably remembers the big bullet points from the ‘94 Conference Finals, but what’s the one thing people most often forget about that series?

There’s a few things. We forget that the players are human beings, and they have lives, and there’s a lot going on sometimes in their lives. Bernie Nicholls, a player on the Devils that year, stands out to me. He had one heck of a series, but emotionally, he was up and down for a year and a half. He was traded from Edmonton to New Jersey, and one of his children was sick, and he eventually died earlier in the season.

This opportunity to get to a championship meant so much to him as a distraction, more than anything else, to real life. He was going back home on days off to be with his family in a time of need. When I talk to people that covered the series — the broadcasters and the writers and people in and around the series — when I tell them about certain bullet points, a lot of them didn’t even know about Bernie Nicholls, and they say, “Wow, I can’t believe that (a) that story slipped through some of the cracks that it did, and (b) that he was able to play and do what he did.” He had a huge Game 5; he scored twice and put the Devils up 3-2. It was actually the last game the Devils won in that series.

You look from Game 1 all the way through Game 7 and beyond — what happened to both teams after winning their Stanley Cups twelve months apart from each other, and I think what makes it the greatest series ever is all those little stories that may have slipped through the cracks, and hopefully we have illustrated some of those.

What about during the games themselves? The point is made that Mike Richter’s performance late in the series is sometimes forgotten.

Right. I don’t think there’s any question that in my time watching this team and covering this team, that Game 6 might have been the best performance of a goaltender that I’ve ever seen. The Devils came out as you’d expect with an opportunity to get to the Stanley Cup Finals at home. They felt they were the better team. They were up 3-2, and they were gonna beat the Rangers. And they just came out for two periods and littered Mike Richter with shots that — to this day, I still don’t know how he made some of those saves. He let in two goals, and that’s probably what leads to the fact that Mike doesn’t get the credit that he deserves — that he was down 2-0 in that game, and he was almost pulled. Of course, Mike Keenan didn’t pull him, and the rest was history.

Marty Brodeur was a rookie on his way to winning the Rookie of the Year award and setting the stage for the greatest career of any goaltender in NHL history. He gets a lot of flack for giving up the goal that he did to Stephane Matteau and the manner in which he did in double overtime. I think a lot of people forget the fact he was 22 years old, and this was the first time for him going through anything like this. And I think what also gets lost is that they were in double overtime of Game 7, and just to be that far in that game, with everything going against them in the Garden — it gets lost how outstanding he was in Game 7. Because he let in a bad goal, quite frankly. But there’s a lot of things like that that get lost.

There were suspensions on both sides. I think people forget that Bernie Nicholls was suspended for a cross-check, and then Jeff Beukeboom was suspended retaliating the next game for the Rangers. There was a lot of rough stuff that went on in the corners in that series, and there was a lot of bad blood. The mind games between both coaches, Keenan benching players, Jacques Lemaire being very short with the media. I could go on forever.

I thought that Neil Smith had some interesting things to say in the book, but athletes sometimes talk in clichés and generalities. Was there anyone that you spoke to that you wish had said more.

Sure. It’s a good point, and I agree Neil was very candid. I don’t think Neil would have become the GM of the Rangers and the architect of a championship team if he wasn’t that way. But I agree with you, yes, there are some. You don’t walk away from a project where you interviewed over 150 people without being disappointed in some. I think Mark Messier, among others — I don’t want to say I was disappointed walking away with the interview with him, but I think that he’s one of these quiet, unassuming leaders that always let his play do the talking. He wasn’t the brash, gimme-that-microphone guy during his career that maybe people think he was, and that certainly hasn’t changed in retirement.

Mark was great for the book. He was very passionate and proud of what he had done, what his team had done, and what that accomplishment meant for the city of New York. He’ll carry that with him forever, there’s no question about it. I think with a guy like Messier, what I learned is it’s easier to talk to other players about him, about what he had done — especially players who were on the Rangers before Mark got there in ’92 as well as other players who may have played with him at other stops. When you talk to those players, you really realize the effect that Mark had, not only on the team, but on the organization and really the city overall as a hockey market. They were just so passionate about how Mark changed the culture of this team. And I think, quite frankly, Mark might just be sick about talking about the same things over and over.

I thought Keenan was the same way. He was such a key figure, in terms of telling Smith which players he did and didn’t want on the roster, and then in the series itself: benching guys, pulling or not pulling Richter. He was playing these mind games, but was he hesitant to talk about the method to his madness?

Yeah, that’s a good question. I think that eighteen years later, bygones are bygones, and it’s about the accomplishment and about what happened in the end. And you also have to remember, quite frankly, that Mike is is retired now but not out of the coaching game forever. I don’t think anyone ever says never. He could get back into the game. When you’re a coach, you keep things close to the vest, and I think when you’re a coach, you’re always a coach. I think Jacques Lemaire is the same way with the Devils, where he didn’t want to talk necessarily about the neutral zone trap as much, and he didn’t want to talk about that defensive style. In the end, I think both coaches, to be honest with you, stick to their systems and stick to their beliefs and only give you what they feel is good enough to put in the book, so I agree with you.

Sounds like John Tortorella during the playoffs last year.

[Laughs.] Yeah, no question. I think that the trend for coaches stands the test of time, there’s no question about that. You know, when you talk about a championship season like that, it’s easy to wax poetic and talk about maybe some of the stuff, but you might drop your guard and say stuff that doesn’t normally get out there, and while Mike is certainly proud of that season — delivering a championship and having to go through all the ups and downs that team did — I think a lot of that stuff that went on behind closed doors I think will always remain behind closed doors.

Howie Rose’s call of Matteau’s goal is the famous one, of course, but Gary Thorne’s on ESPN is kind of terrible. He says something like, “1940 is history,” which is a crazy thing to say at the end of the Conference Finals. When you talked to Thorne, did say anything about that? Express any regret that he kind of blew that call?

He didn’t, but Howie’s call lives on forever. That’s one thing that was great about the ‘94 series: There were so many calls. There was a Canadian call, there was a Devils radio call, there was a Rangers call, there was an ESPN call. There were so many people calling that series, somebody’s going to stand out, no question about it, and others will be left to the side. But you also have to understand that yes, when you’re looking at a game ending the way it did, it’s unlike any other sport, where there’s buildup. If it was a game-winning field goal, there’s buildup. Hockey just happens, and sudden death truly is sudden death. And when you look back at the goal, there is ample reason to think that people could not believe that the goal went in and maybe weren’t as sharp as they needed to be because of the freak nature of the way it went in. And Howie was the best with all that. He wasn’t so sure either. He took a risk. He saw the celebration from Matteau, and he gave it his best shot that it was him. It’s funny to look back on it with him. He knew that he almost blew it, because Esa Tikkanen was in that crease, and he could have gotten it. It was a very, very difficult play to call, and when you look back on it and watch it as many times as I did in researching this book, you can understand that some people may not have been as sharp, and some people also had to take a chance on who scored the goal. Obviously, Howie was right.