In countries with a great deal of sunshine, it makes sense to want to install solar panels wherever possible. But sometimes, even if that goal succeeds, the work isn’t quite done. Take Bangladesh: Over the past 15 years, the country has managed to provide, through an ambitious government program, millions of solar panels and batteries; the country today has more than 5 million solar-home systems. That statistic puts Bangladesh high in the running for the most widespread embrace of solar power in the world, but those solar panels are largely not networked the way they are elsewhere. One European-owned start-up called SolShare is trying to turn these disparate power sources into a makeshift grid, or grids.

In the U.S. and Europe, solar-home systems are hooked into the broader electrical grid. If a homeowner produces more electricity than the home needs, in many cases, that homeowner can actually sell surplus electricity back to the grid. But many of the systems in Bangladesh were installed in homes or businesses that were never hooked up to the power grid in the first place. That means that they’re now closed-loop systems, unable to share surplus power. And, due to the smallish batteries provided by the government in these systems, there’s often quite a bit of surplus power in one house, while next door, there’s still no electricity at all. SolShare managing director Sebastian Groh estimates that 30 percent of the power generated by these panels is simply lost because the solar-panel owner doesn’t need it, and there’s nowhere for it to go.

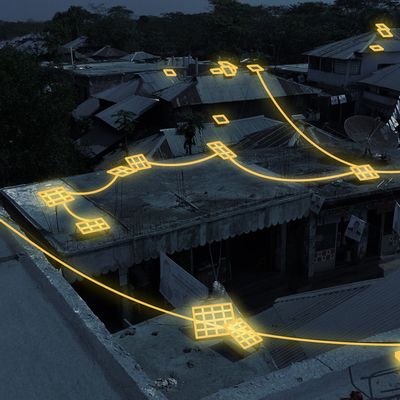

SolShare is aiming to create what they call “nanogrids”: tiny, localized electrical grids, where anyone with a solar panel can be their own power plant. The company installs small smart meters in the houses of people with solar panels, and connects them to other houses with electrical cabling, the same way any power company would. Those users with solar panels have the option to decide how much of their surplus power to sell; many just choose to automatically sell any power once their own batteries are full.

Houses without solar panels that have been linked into these localized grids can buy electricity from their neighbors in the same way those in the cities buy power from an electrical utility. All the buying and selling is done with a digital wallet, which can be cashed out at any point. “SolShare here acts as a platform provider, charging a transaction fee for every Wh traded in our Solgrids,” says Groh.

About 25 percent of Bangladesh’s population is not connected to the power grid. Power off the grid is wildly expensive; without panels or access to a larger electrical grid, Bangladeshis were sometimes paying a hundred times more for electricity yielded by generators than someone in a city might pay. “With our approach, the utilization of clean energy from solar can now even reach low-income households that could not be reached before, by making energy access 30 to 50 percent cheaper than any stand-alone system of comparable quality,” says Groh.

The fact that people can now earn money from their panels can also spur expansion. Previously, the panels were as affordable as possible at just a few hundred dollars, and with very low interest on payments. But 25 percent of Bangladeshis live in poverty, and even those payments might prove too much. With a system like SolShare, which brings in revenue for solar-panel owners, people might be more inclined to jump into the system. After all, they might owe some money each month for payments on the panels, but those panels are also earning income.

SolShare says it has already installed grids covering 15,000 people in Bangladesh, and, ambitiously, Groh says he wants to grow that to 1 million people by 2022. “I am waiting for the day, which I don’t reckon to be too far away, that we trade our solar power from house to house here in Dhaka, and for that matter, in fact, all around the world,” says Groh.