The wave rolls in every day at noon Manhattan time. It gathers invisibly, out in the digital netherscape. A few minutes before the hour, the online retailer Gilt Groupe blasts out an e-mail, and a hush falls over many a workplace, as phone calls are cut short and spreadsheets minimized. Gilt Groupe is in the business of selling high fashion at deep discounts, and as you might deduce from the company’s name, with its Frenchified “e,” it presents itself as an exclusive club. In reality, that’s just artifice—Gilt is a viral-marketing phenomenon. During the hour after its weekday sales kick off, between noon and 1 p.m., the company claims, its site is visited by an average of roughly 100,000 shoppers. For that time, it might as well be the most crowded store in New York.

Countering predictions that a deep recession would mean the death of demand for luxuries—a new flagellant aesthetic—Gilt has thrived through the downturn, selling labels like Rodarte, Derek Lam, Christian Louboutin at prices around 70 percent off retail. Within the e-commerce sector, what Gilt does is called a “flash sale,” or a virtual version of a designer sample sale. The site’s best finds disappear immediately, and scarcity promotes covetousness, competition, and loyal attention. A number of other recently launched sites employ a similar business model, but none has had as much of an effect on the New York fashion industry as Gilt Groupe. Its executives say that in 2009, just two years after its launch, it posted revenues of $170 million—a stunning figure for a start-up. (Internal sales and site-traffic numbers are impossible to confirm, however, as Gilt is a private company, so caveat emptor.) This year, the company is forecasting that its revenues will more than double.

Gilt Groupe recently surpassed 2 million members, three quarters of whom are female, and they’re disproportionately young and high-income: basically a designer’s notion of the ideal customers. Gilt seldom advertises; instead it crawls through personal networks, offering current members incentives to invite their friends to join the Groupe. “All of a sudden, one day, every woman I knew was on it,” says a friend of mine who worked last year as an executive at a major New York corporation. She says her colleagues would often push lunchtime meetings back a few minutes just so they could check out Gilt promptly at noon. Nobody wanted to miss the wave.

The success that Gilt has enjoyed stands in stark contrast to the gloomy mood that has gripped the rest of the fashion industry. “What Gilt did, I think it’s a combination of vision and smarts and timing,” says Steven Kolb, executive director of the Council of Fashion Designers of America, which has been working in partnership with Gilt Groupe, acting as a bridge between the company and designers. Last year, as incomes tightened and the fashion industry was left with ruinous amounts of inventory, the company’s business model proved to be a countercyclical savior, sucking up goods that otherwise would have moldered. “There was an abundance of merchandise that needed an outlet,” Kolb explains. “They created a genuine fashion space that felt right and had an aesthetic and clearly had a consumer base.”

In the view of Gilt Groupe executives, this is what makes the business work: It offers designers a safety net—and potentially more. Some designers have found Gilt’s model lucrative enough that they’ve decided to do away with their brick-and-mortar sample sales; others are now making clothes specifically for the site. “We really strategize with these brands,” says Alexandra Wilkis Wilson, one of Gilt’s founders. “We’re not just about taking leftovers.”

To a fashion business racked by losses and self-doubt, Gilt’s success suggests that however pestilential the times, consumers still desire finer things. The bad news is, they don’t want to pay retail. Gilt executives say that customers prize the site as an experimental channel, a way of trading up to a label that they might not be able to afford at full price. But another possible scenario—one more troubling to the industry’s future—is that Gilt customers are taking a good deal where they can find it, and, perhaps, adjusting their cost expectations downward.

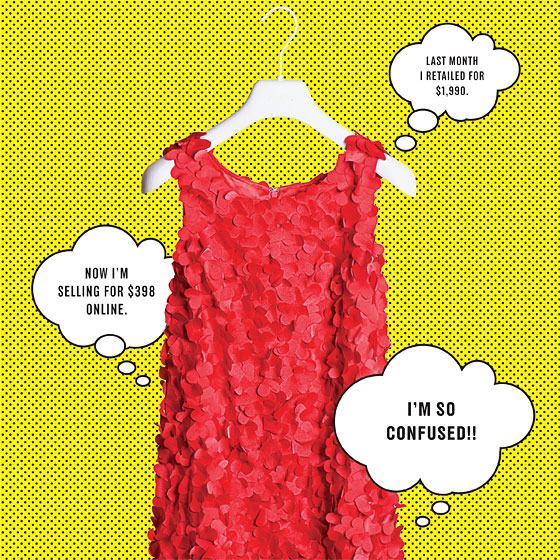

Designers take a Victorian stance toward discounting: Almost everyone does it, but nobody likes to admit it. Before the recession, many high-end labels wouldn’t have been caught dead disposing of their overstock in a forum as public as a website, for fear of debasement, but these days, brand integrity looks like, well, a luxury. Still, many designers wonder about the long-term consequences of the bargain they’ve struck. They worry that Gilt and its brethren may be undermining the expectation, carefully cultivated over many years, that the finest things always come at a premium. “There is always a risk to the integrity of your brand whenever you discount,” said Milton Pedraza, CEO of the Luxury Institute, a research and marketing group. “What you’re telling consumers is ‘We’re really kidding, it’s not really as valuable as we told you it was.’ ”

In its self-presentation, Gilt engages in a fair amount of spell-casting—it’s as invested in projecting a high-end image as any of the designers that it sells. But at its heart, its business is simple, and very of-this-moment: It capitalizes on reduced expectations of value. A couple of weeks ago, during her performance at the Grammy Awards, the singer Carrie Underwood wore a gold strapless gown by the designer Reem Acra. The very next day, supposedly by coincidence, it was on sale at Gilt, marked down by almost $4,000, to $1,498. For Gilt, it was a publicity coup, picked up by The Wall Street Journal; for Acra, the moment must have tasted slightly bitter. (Acra’s publicist declined to comment.) “I think this is one of the ongoing issues of the American merchant,” says Paco Underhill, a marketing consultant and the author of Why We Buy: The Science of Shopping. “The customer looks out at the offering and says, ‘I don’t know what this is really worth.’ ”

An hour before noon on December 16, a Wednesday at the height of the crucial Christmas-shopping season, Gilt Groupe’s warehouse in the Brooklyn Navy Yard was abuzz with activity. Clothing arrives in bulk, and it’s supposed to be out the door in about two weeks. “Whereas a department store might be able to move a certain amount of product in a season,” said Amanda Graber, a Gilt public-relations manager, “we can do it in 36 hours.”

Graber and Kate Furst, the company’s director of sales operations, took me on a tour, every so often stopping to pick up an item—like a wool Burberry coat, retail price $2,995, Gilt price $1,198—and uttering an approving ooooh! We walked past a string of brightly lit studios, where photographers were staging modeling shoots. At a far wall, amid a tangle of disgorged clothing, employees sat inspecting stacks of incoming samples: James Jeans, a ribbed sweater by Alexander Wang. As the noon hour passed, phones began to chirp inside Gilt’s glassed-in customer-service center. Many online shoppers want fashion advice, and Gilt’s representatives often act as gentle guides. “Have you ever purchased anything from John Varvatos?” Todd Metzker, a stubbly part-time actor, asked an uncertain male caller who was looking at shoes.

One floor down, warehouse workers, shouting in Spanish, were wheeling cardboard boxes down long rows of shelves. Along conveyor belts, women folded Trovata hoodies, wrapped them in black tissue paper, and placed them into boxes, as machines dispensed shipping labels, dispatching purchases to Chicago, Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., and the Upper East Side. Into each box, the women slipped a little card with gold cursive lettering. “Thank you for your purchase,” it read, and was signed “Alexis + Alexandra—the founders.”

Alexis Maybank and Alexandra Wilkis Wilson are the public face of Gilt Groupe and the exemplars of its taste. A pair of stylish blondes, they represent the company on television and at events like Fashion Week, where Gilt has sponsored up-and-coming designers, and they keep a daily blog on the site, highlighting their favorite finds. Every successful company has a creation myth, and Gilt Groupe’s goes like this: Maybank and Wilson became friends at Harvard, where they lived in Lowell House as undergrads and later returned to earn their M.B.A.’s. Maybank learned about e-commerce as an executive at eBay, while Wilson went into fashion, working for companies like Louis Vuitton. Eventually, they united their experience and started Gilt, in an inspired burst of Carrie Bradshaw entrepreneurialism.

The full story is a little less glamorous, and it begins with Kevin Ryan. Ryan was the CEO of the online ad company DoubleClick until 2005, when it was sold for more than $1 billion, and he’s now an investor who presides over a stable of start-ups. In Ryan’s telling, the eureka moment occurred one day when he happened to see a long line of women standing outside a storefront on 18th Street, waiting to get into a Marc Jacobs sample sale. “All I could think was, if there are 200 people who are willing to stand in this line, that means in the United States there are probably hundreds of thousands,” Ryan says. “But they don’t live in New York, they’re busy right now, they just can’t do that. And I can bring this sample sale to them.”

Ryan was aware that a French company called Vente Privée was raking in money by selling fashion overstock, and he thought its business model could work just as well in America. He hired two computer engineers to start building a website, and then found Maybank through an executive-search firm, hiring her first as the company’s chief operating officer and later promoting her to CEO. Maybank brought in Wilson a few months later to act as Gilt’s emissary to the fashion world.

From the beginning, the company’s key challenge was persuading designers to supply the site with inventory. At the time, 2007, it wasn’t an easy sell. That was the year of the hedge fund, when the world’s population of millionaires peaked. Designers could afford to turn up their noses, and many did.

Of course, most designers sell at affordable price points when it suits their interests. It’s called “going mass.” Designers discovered long ago that they could make decent margins in the discount market, and to drive up profits further, some began manufacturing cheaper-quality clothing meant specifically for sale at outlet malls. But nobody publicizes this. “They need to be secretive,” says John Mincarelli, a professor of fashion-merchandising management at the Fashion Institute of Technology. “The last thing the fashion industry wants is for the consumer to understand how the industry operates.”

Gilt Groupe’s solution to luring high-end designers was to project selectivity and taste. It launched with just 15,000 members, many of whom came through Maybank’s and Wilson’s own friendship networks—the right kind of people. If you’re not a member and you go to gilt.com, you’re met by a log-in page explaining that you must apply for one of a “limited” number of memberships (although in reality, everyone who asks for an invitation gets one). Once past the virtual doorman, the site has high production values and a muted look that eschews loud colors or flashing “sale” signs. Gilt Groupe executives say they take pains to make it appear as if everything on offer has been carefully culled and curated.

“The last thing the fashion industry wants is for the consumer to understand how the industry operates.”

Putting the site behind a wall also means that merchandise doesn’t pop up on search engines. Gilt’s sales last just 36 hours, and afterward, items are removed from the site. It is all meant to look very discreet. (That’s a word Gilt executives use a lot.) Most attractive from the designer’s financial standpoint, Gilt offers to purchase inventory outright, paying substantially less than the wholesale price but assuming all the risk. If something doesn’t sell on the site, the company promises that it will eat the loss—re-posting the merchandise a few times, and finally conducting an internal employee fire sale—rather than pass the clothes along to a chintzier outlet like Daffy’s. Still, Wilson admits that designers like Marc Jacobs and Tory Burch were wary at first. “They initially wanted to watch from afar and see what we were doing,” she says, “before they could become comfortable trusting us with their most prized possessions.”

The first designers to work with Gilt came through personal connections. As business-school students, Wilson and Maybank had done a field-study project for the designer Zac Posen. In November 2007, when Gilt Groupe launched, it was with a Posen sale. “I did it, at that moment, purely out of loyalty,” says Susan Posen, who runs her son’s company, adding that she had to overcome “a little bit of concern about, was I risking our brand?” But in the end, the sale “just blew out,” she says, and Gilt Groupe was on its way.

Within months, Gilt Groupe’s membership had multiplied sevenfold. One morning, the site was mentioned briefly on The View, and Gilt was deluged with 60,000 invitation requests. It soon became clear that the company’s greatest challenge was going to be expanding its supply to keep up with demand. At a department store, a designer’s sell-through rates—the proportion of inventory that is actually purchased—might be around 65 percent over a twelve-week season, but on Gilt, several designers told me, sell-through rates can top 90 percent. Its customers buy everything.

Still, so long as the global market for luxury goods stayed hot, growing at an average annual rate of 8 percent a year, Gilt was likely to remain a niche business. “It’s not that hard to sell things when you put them at 50 or 70 percent off,” says Sucharita Mulpuru, an online-retail analyst at Forrester Research. “The challenge is to get merchandise at this sale level.”

But then Gilt got lucky. The world economy blew up. With shocking suddenness, $11 trillion of American wealth dematerialized, leaving the country awash in unwanted extravagances. Between the autumns of 2008 and 2009, according to Bain Capital, as little as 25 percent of all luxury goods moved at full price, and nearly half of all items didn’t sell all season. Some department stores canceled orders from designers, or refused to pay for shipped merchandise. Quite a few smaller retailers went out of business entirely. That was when Gilt stepped forward with its checkbook, and said good-bye to its supply problem.

“They came about at an interesting time,” says Robert Tagliapietra, half of the critically acclaimed design team Costello Tagliapietra. “A lot of young designers had a lot of extra product sitting around.” Labels like Armani or Prada are frontispieces for multinational corporations, which have warehouses, factory outlets, and reserve funds, but a substantial number of high-fashion designers operate as small businesses and live from season to season. Some, like Christian Lacroix, haven’t made it through the recession, while others, like Zac Posen. , are enduring public financial struggles. Facing double-digit sales declines, Posen told the Times recently that his company is in “survival mode.”

In hard times, maintaining appearances begins to seem less important. For designers, Gilt Groupe and the other flash-sale sites offered a quick and seamless way to cut glut and restore some cash flow. “You sell out,” Tagliapietra says, “within an hour.”

The designer Lela Rose cuts to what she sees to be the heart of the present unrest in fashion: “Your core designer customer is going the way of the dinosaur.” For a while, Rose says, she didn’t know what to make of sites like Gilt Groupe. She understood the argument that discounts expose her brand to a youthful demographic, and considered it possible that those buyers might someday graduate to paying retail. But she could see the scenario playing out the other way around just as easily. “They might be saying, ‘That’s what I bought when I had no money,’ and now they’re used to paying the sale price,” Rose says. Nonetheless, she’s decided to give in to the phenomenon, recently doing a sale with Gilt’s competitor, Rue La La. “It’s kind of where shopping is going right now,” she reflects. “This kind of ‘fun, fast, get a great deal’ ethic is very appealing.”

Over the last year, most every label you can name has done a flash sale on one site or another, and the presence of good company has washed away some of the liquidator stigma. Still, few of Gilt Groupe’s suppliers are eager to boast about the relationship. Numerous design firms, including some that Gilt executives told me were important supporters of their enterprise, declined to comment for this story. One got so nervous that a Gilt spokeswoman begged me not to mention her name in this article, despite the fact that the designer’s own publicist had trumpeted her Gilt sales on Twitter.

Robert Tagliapietra, who has done three sales with Gilt Groupe now, is happy to profess his affection for the company, which sponsored one of his label’s Fashion Week shows. But he adds that he, like many others, is concerned that discounting may become a self-reinforcing loop. “You don’t want to train customers to expect sales, because at the end of the day these clothes do cost a lot to make,” Tagliapietra says. Designers pay a great deal for fine fabric and hand-stitching. “Clothes aren’t arbitrarily expensive,” he says. “The profit margins for designer fashion are surprisingly small.”

“Gilt is really there for you to cut your losses—you aren’t making any money,” says another designer—let’s call her Lisa. When Gilt Groupe first reached out to her, Lisa was skeptical, but then she tried out the website, buying something by Helmut Lang. She was impressed by how smoothly the process worked, and she’s since done several sales herself. Why would she, if she’s only breaking even? Lisa explains that selling on Gilt benefits her in several ways beyond liquidation. For instance, the company is now sending buyers to place orders with designers at the beginning of the season, for what is basically planned overstock. When Lisa reaches a certain production threshold, her price per unit goes down, which means that she makes higher margins on the portion of the order that sells at retail. Thus, even though her Gilt sales are a wash, she makes more money overall.

Cutting such deals is one way that Gilt Groupe has attacked a looming problem: sustainability. “This is an easy business to start; it’s a really hard business to scale,” says Susan Lyne, Gilt Groupe’s present CEO, who came aboard in September 2008. (She replaced Alexis Maybank, who remains with the company in a strategy-making role.) Lyne’s hiring marked a major step in Gilt Groupe’s maturation: As a former president of the ABC television network and of Martha Stewart’s multimedia empire, she brought the company serious gravitas. She has overseen a period of furious expansion: Gilt has quintupled the size of its workforce, to almost 350 employees, stepped up its spread into new product lines, and opened a subsidiary in Japan. Two years ago, it conducted three sales a week; now it does an average of 70.

Meanwhile, the business keeps getting more crowded. Competitors like Rue La La are getting bigger, too, and it seems like every day brings the debut of another imitator: Those launched in just the last year include Beyond the Rack, the beauty-products site Market for Drama, and Swirl, a flash-sale spinoff of the DailyCandy empire. Even some high-end department stores, like Saks Fifth Avenue and Neiman Marcus, are experimenting with flash sales on their websites. “We were intrigued with what was going on out there in the industry,” says Denise Incandela, president of Saks’ online division, which thrived last year in comparison with the rest of the company.

The department stores—the actual stores, the ones that sell full-price clothing—still exert enormous power over the industry, and no one expects that dynamic to disappear anytime soon. Designers and Gilt executives say that department stores have been vigilant in watching whether clothes appear on Gilt in advance of their scheduled markdowns on the floor—a big no-no. But many in the fashion industry worry that the success of sites like Gilt is hastening a trend that was gathering steam even before the recession: the decline of the meandering, tactile experience of shopping. “What really scares me the most is, what’s going to happen to department stores, and what’s going to happen to the specialty store?” wonders Lela Rose, who added that she bought almost all of her own Christmas gifts online this year. “Where do we go to touch it, and look at it, and to be inspired?” More important: Where will anyone pay retail?

For Gilt Groupe, the multiplying number of retailers who follow a similar business model has a practical consequence: There’s now far less surplus product to go around. It’s clear that liquidation alone won’t keep the business growing anymore. The inventory left behind by the crash of 2008 has worked its way through the system, and most designers have adjusted their production downward. So as Gilt Groupe’s membership keeps growing, the company has had to work frantically to keep pace with new appetites, and to come up with creative ways to expand its pipeline.

One icy morning last month, I went to see how the company is meeting its problem of supply, accompanying a pair of buyers on a visit to the boutique jewelry-design firm Dannijo. The designers behind the line, sisters Danielle and Jodie Snyder, are both in their mid-twenties and were working out of an apartment in Battery Park City. For roughly an hour, they showed off rings, earrings, and necklaces that were arrayed across a coffee table, and buyers Renee Klein and Meredith Blacker sized up what would sell.

“I’m in love with this,” Blacker said, draping a Swarovski-crystal-plated bracelet over her wrist.

“A little aggressive,” Klein told Blacker as she tried on a spiky oxidized-silver necklace.

“Gilt doesn’t tell you, as a shopper, that it’s ‘exclusive for us,’ ” admits one designer. “They want you to think it is part of the regular collection.”

The buyers weren’t looking for surplus inventory. They were going to commission pieces specially made for Gilt Groupe—a growing segment of the company’s business. Susan Lyne told me that Gilt knows there are “sweet-spot prices” for its membership. “Anything that’s between $100 and $250,” she said, “the vast majority of our customers are comfortable with that.” With liquidation, where price is determined by what Gilt pays for existing merchandise, it’s not always simple to hit the sweet spot. But by commissioning pieces, Gilt can get a guaranteed supply designed to its own price specifications. At the appointment with Dannijo, the jewelry buyers were looking at the sisters’ latest collections to determine how they could be retrofitted for Gilt. “It’s the same quality, everything’s still handmade in New York,” Jodie Snyder said later. “It’s just different products that might not be as intricate, so that we can make them at a lower price point.”

Gilt Groupe is using much the same model to expand its inventory of clothing, commissioning designers to make clothes just for the site. This year, Lyne says, 35 to 40 percent of Gilt’s women’s apparel will be acquired through this channel. For designers, cutting clothes specifically for Gilt can be lucrative, because it offers a way to repurpose intellectual property, such as popular looks that may be a couple of years old. A designer may reduce production costs by using less-expensive materials, say wool from Scotland instead of Italy, or by using a little less stitching in the places buyers don’t see. More than one fashion executive told me that they had used flash sales as an opportunity to dust off some leftover fabric, turning a sunk cost into a substantial profit.

But neither Gilt nor the designers have any interest in letting customers know which items were made specifically for the site. “Gilt doesn’t tell you, as a shopper, that it’s ‘exclusive for us,’ ” admits one designer. “I think they want the shopper to think it is part of the regular collection.” The “discount” advertised on Gilt’s site is based on what the designer calculates a department store could have charged, even though the item was never intended to sell retail.

There’s some logic to this sleight of hand: Gilt operates at much lower costs than traditional retailers, and can pass its savings along to the customer. But Gilt has to be careful. It can’t afford to have its customers questioning whether that “retail” price is bogus; the allure of its sales is all about making its buyers feel like they’re smart enough, inside enough, to get in on a steal. Devoted shoppers and fashion bloggers watch the site closely, alert to any whiff of manipulation. On at least one occasion, reported in a January Wall Street Journal column, their vigilance exposed what Gilt described as a pricing mix-up. It involved a scarf, listed on Gilt as a $300 value before its discount, nearly identical to one a blogger discovered to be selling at retail at Neiman Marcus for $195.

Sucharita Mulpuru, the Forrester analyst, questions whether Gilt Groupe, as a business, might be the equivalent of that $300 scarf. “To me,” she says, “there is a big possibility that there is a house of cards here.” There’s only so much finery in the world, and the more Gilt expands, the more it strains to offer the very qualities that have set the site apart: selectivity, community, and quality. Some early Gilt Groupe adopters complain that the site is now infested with labels they don’t recognize. The company currently works with over 700 brands, and has been expanding into new products far removed from its core business. There’s a spinoff travel website called Jetsetter, and Gilt Fuse, which features lower-priced brands like American Apparel. You can now buy men’s clothes, kids’ clothes, travel packages, household goods, wine, spa treatments, and the occasional motorcycle.

Shawn Milne, an e-commerce analyst at Janney Montgomery Scott, argues that diversification is vital to Gilt Groupe’s future. “Clearly, for these business models to really pay off, they are going to have to prove to investors that they can get outside of just female-oriented, luxury-related fashion products,” he says. Milne believes that Gilt Groupe, which was valued at $400 million during its most recent round of venture-capital financing, is scaling up in advance of an IPO. The moment may be ripe: Last year, Rue La La was sold to a publicly traded e-commerce company, in a transaction that could be worth up to $350 million, and there have been persistent reports that Amazon is considering a multibillion-dollar deal to acquire Vente Privée. (For the record, Kevin Ryan says he is exploring taking Gilt Groupe public, but not before next year at the earliest.)

“This is a much bigger industry than most people think,” Susan Lyne says. “If you look at T.J. Maxx, it’s a $20 billion company.” Of course, invoking the example of the strip-mall discounter—Ryan did it, too—takes us quite a distance from Gilt’s original mission. The company clearly recognizes the tension. Last fall, in response to the concerns that the site was getting too crowded, the company created Gilt Noir, a special truly exclusive loyalty program, which gives big spenders and VIPs advance access to sales, and brings private promotions with designers—the company won’t say which ones—who refuse to sell on regular Gilt. Over time, company executives say, the idea is to divide Gilt Groupe into ever-smaller segments, showing customers only those items that fit into their style, or their price range.

By putting every member in her place, Gilt hopes to preserve its aura of taste—and the premise of a luxury market. But it may be that the greater danger to Gilt, over the long run, is posed by the very thing that pulls so many people into the wave each day: those low, low prices. Paco Underhill told me that discounting “is sort of like heroin: The more you use it, the harder it is to stop.” Economists have their own term for this: They say prices are “sticky.” If you see a low number once, it’s a bargain; see it a dozen times, and it adheres. Each day at noon, Gilt meets its customers with more brands, more offerings, more markdowns. Yet its own brand identity is tethered to the very thing it undermines: perceptions of intrinsic value. Last week, a Marc Jacobs leather bomber jacket, retail price $2,420, was on sale for $548. Was that a deal? It depends how confident you are that someone else would have paid full price for it. A discount is like a shadow—it only exists in relation to an object of actual worth.

To Become a Gilt Groupe Member

Register here.