It’s after midnight on a recent Friday in the Boom Boom Room atop the Standard Hotel. The floor-to-ceiling windows look down on the frozen city as the inky sheen of the Hudson bends away from us. “Let’s All Chant,” the hedonistic disco song from one of Faye Dunaway’s fashion-shoot scenes in Eyes of Laura Mars, throbs over the sound system. Courtney Love, in granny glasses and a crazy Stevie Nicks ensemble, huddles conspiratorially over a BlackBerry with Michael Stipe. Donna Karan, Terry Richardson, Richard Prince, and Simon Hammerstein are dispersed among the glitter.

Lorenzo Martone is there, crowded into one of the seventies-style banquettes listening to his friends chatter happy late-night fashion nonsense, waiting for the right time to get up and dance. “You feel like you’re at the top of the world here,” he says in his deep, Brazilian-accented voice, nuzzling close to be heard over the din. Martone, who’s 30, arrived in New York just two and a half years ago, another canny, good-looking, well-mannered fashion PR guy of the sort who decorates places like this. But for the past year, he’s been Marc Jacobs’s fiancé. Now he’s surrounded by celebrities, all of whom know him.

Martone (or Lolo, as his friends call him, like he’s a big puppy) loves to touch people. He has a powerful, and soothing, physical presence. He even smells reassuringly expensive (his cologne is called Poivres à Trois, which, he jokes, translates into “a pepper threesome”). He dresses in a happy, colorful uniform of tight shirts, suspenders, skinny jeans, scrunchy socks, and high-top sneakers, all by labels like Lanvin, Dior, and Marc Jacobs (he says he gets a slightly more than 20 percent-off VIP discount). For the last two years, Martone, who speaks four languages and has an M.B.A. in, of all things, luxury-brand management, has worked as a strategic planner for Chandelier Creative, a fashion and beauty ad agency with clients like Parfums Givenchy, Nars Cosmetics, and threeASFOUR.

Tonight he’s wearing a Chanel watch encircled with diamonds, which he got from Jacobs after “I caught him smoking in action in Venice,” he says. Martone hates smoking, and they got in a fight over the fact that Jacobs hadn’t quit like he said he had. “Between the Taurus sign and being Latin, I probably reacted … ” He trails off. “And all I know, we were shopping in Venice and I got this watch as a gift.”

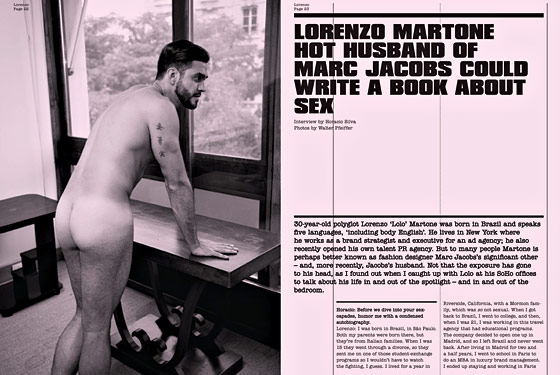

Martone wears two rings. One he bought himself, with a matching one for Jacobs—pink gold from Boucheron, “which is Marc’s favorite brand.” He’s had bears engraved on the inside. “We call each other bears because of our facial hair and all that,” he says. “I have an attraction for beards. It’s kind of a fetish.” Jacobs grew one after they started dating. “I’ve molded him in my image,” Martone says, not quite seriously. The other, an infinity ring of emerald-cut diamonds, Jacobs gave to Martone off his own finger after they’d been together for eight months. “It was not an engagement ring, just a gift,” Martone says. Like Elizabeth Bennet, the heroine of his beloved Pride and Prejudice, he has his share of status conflicts over his marriage prospect. But then again, Jane Austen never imagined the blogosphere. Or for that matter, Butt magazine, the arty gay quarterly that Martone posed bare-bottomed for in the spring 2010 issue, discussing their wedding, as well as his personal sexual history.

Marc Jacobs, who advertises in Butt and has been interviewed in it, too, is one of the great neurotic, uncompromising, brutally self-searching New York auteurs—complete with the usual drug history. His story is complicated by the sad fact that he’s estranged from his mother and siblings, and that his father died when he was young. That profile, for whatever reason, doesn’t often accommodate connubial bliss.

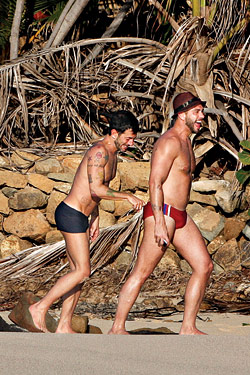

But about three years ago, Jacobs, who is 46, had a transformative midlife crisis. He got sober and got thin and got ever more tattooed. He became exhibitionistic, delighting in his workout routine. Suddenly photos of Marc Jacobs sleeveless, shirtless, or just in his underpants became commonplace. Meanwhile, he was dating—the old, schlumpier Jacobs had never seemed to be dating—a former hustler, Jason Preston, who tattooed MARC JACOBS on his forearm. Then Jacobs went back to rehab, then re-dated and finally ended it with Preston. It was a very public spectacle, and with it Jacobs’s repressed persona was replaced with one that didn’t seem to care what anybody else was thinking. Whatever was going on on the inside, he appeared to be a bolder, more confident man.

Martone made his public debut by Jacobs’s side at the Costume Institute Gala in May 2008. Early last year, they announced their engagement.

Because same-sex marriage is legal in Massachusetts, rumors circulated that it would happen last summer in Provincetown, where Jacobs’s business partner, Robert Duffy, has a house. But that didn’t happen. Then pictures surfaced of a party hosted by Larry Gagosian on St. Barts New Year’s Eve, complete with a cake topped with miniatures of Martone and Jacobs, which either was or was not their big day. At the time, they said it was merely an engagement party, but in the Butt Q&A, Martone called it an “intimate ceremony.” (Though an earlier version of the interview appeared on Gawker, calling it an “intimate wedding.”) So which was it? “We considered it a wedding, or a union. I don’t think we are as concerned as everybody else in labeling things in such a way,” Martone says.

Wedding or not, in many ways, 2010 is the year of the roll out of Lorenzo Martone, successful and well-known Manhattanite. Last fall, he teamed up with former modeling agent Ryan Brown to start an outfit called ARC NY Talent PR (the name, he says, doesn’t stand for anything, he just liked the optimistic sound of it, the upward trajectory).

Martone grew up in an upper-middle-class Italian family in São Paulo. His parents divorced when he was a teenager, and they sent him to be an exchange student with a Mormon family in Riverside, California. He came out at 18, following a backpacking trip in Europe. After college in Brazil, the travel agency he worked for sent him to Madrid, and he decided to stay. He tended to date older guys, but the longest relationship he had before Jacobs, who’s sixteen years his senior, was about a year and a half.

In 2004, he moved to Paris to get his M.B.A., and realized he had to adapt. For one thing, something was wrong with his wardrobe. “Madrid is not a very fashion-oriented place,” he says. He dressed too colorfully; in Paris “everyone is wearing black and gray. So I learned about Dior Homme and became a big fan of Hedi Slimane and changed into someone conscious about fashion who admires design.” Martone started going to L’Usine Opéra, a gym with a gay fashion crowd that at the time was the David Barton of Paris. Among those who worked out there were John Galliano, Stefano Pilati, Rick Owens—and Marc Jacobs.

How they met, Martone’s take:

One day at L’Usine Opéra, he and Jacobs—who’d already changed his habits to become more healthy—were running on neighboring treadmills. Martone invited Jacobs to go running with some friends in the Jardin du Luxembourg. “He never actually came,” Martone says. “But we kept in touch, saying hi.” Were you flirting? “I guess checking out each other’s body but not really flirting.” You were attracted to him? “I was like, ‘Oh my God.’ He looks like a little boy without those tattoos. When you live in Paris, you’re used to all these proper kids, a little preppy, a little fashion-forward, a little feminine and longer hair. So when you see a cool New Yorker with diamonds and tattoos—I was just, ‘Wow.’ So we just kept this friendship. I had this boyfriend at a certain point who also worked at Louis Vuitton, so we’d all socialize together.”

But then Martone left Paris for New York. “I get bored so quickly, I need to entertain myself,” he says. “I always felt like, ‘Oh, I already speak the language, I already know everyone.’ When I felt it wasn’t enough for me anymore, I just moved continents and countries.” He also felt that his career advancement was going to be limited, since he wasn’t French.

In New York, he and Jacobs continued to spend time with each other. “When he broke up with [Preston] in January 2008, we started going out, the two of us versus in groups—the theater, then dinner. It started having this format, more of a date.” Their first kiss happened after they saw Spring Awakening. “Then to Nobu, then we kissed and more. We slept together.” Soon enough, Jacobs started introducing him as his boyfriend, though they never talked about it. Martone didn’t mind. “I was flattered. That’s what I wanted, too.”

The windows of ARC’s sleek, snug Soho offices face those of Marc Jacobs’s vast atelier across the street. Martone says ARC’s goal is to “revive the supermodel.” It currently has seven clients, four of whom are in the most recent Sports Illustrated swimsuit-issue: Julie Ordon, Irina Shayk, Julie Henderson, and Jessica White. The others are Fernanda Motta (host of Brazil’s Next Top Model), Alessandra Ambrosio (Victoria’s Secret), as well as SI alum Valeria Mazza. (Until recently, Lydia Hearst was a client, too.)

The models pay ARC a retainer to help them raise their profiles and diversify their brands into acting, music, or product development, which will, ideally, turn them into supermodels. Henderson is launching a line of skin-care products based on a grapefruit her grandfather bred in Texas, and White wants to sing R&B (she is very proud of her version of Prince’s “Pop Life”). There are big, sultry close-ups of the girls on the walls of ARC’s offices.

Martone is a sort of lyrical visionary for the company. This June, for instance, ARC is hosting a party for Ambrosio atop the Empire Hotel next to Lincoln Center. The party will be called “Follow the Sun,” to play up her beach-goddess allure. “Alessandra Ambrosio stands for summer,” goes some copy Martone wrote. “It’s her passion, it’s her fashion, it’s her obsession.” Another bit reads: “Alessandra is the sun … let’s follow her.” Martone loves models. “They have a certain enchantment that I’m attracted to,” he says. At a Victoria’s Secret product-launch event that Ambrosio hosts, Martone trails her and fusses over her. He loves how she (and, to tell the truth, all models) toss around their big hair, and often does it himself with his smaller hair, in imitation of them. “Look at her waist,” he says of Ambrosio, enraptured. “It’s amazing. It’s not human!”

One afternoon at ARC, Martone and Brown sit down with Francesca Hammerstein, whose husband, Simon, owns the nightclub The Box, as well as an Austrian named Sandro Suppnig, the creative director for a media outfit called Vision On, to plan a party for ARC during Fashion Week. Vision On has created a short film called La Demimondaine starring the model Iris Strubegger that will screen at the event. (You can watch it online; it seems like an extended fragrance commercial.)

They pass around a box of Dean & DeLuca cookies and brainstorm. “I think we need food no matter what happens,” says Martone. “I don’t like parties without food.” Martone describes himself, and others describe him, as decisive, and he drives the meeting.

Martone bought matching pink-gold rings for him and Jacobs and had bears engraved on the inside. Martone calls Jacobs “Babybear,” and he calls him “Papabear.”

For one thing, Martone insists that the party be branded “Not Now, I’m Dancing.” He wants all ARC parties to use this slogan. “We thought that was such a model’s attitude,” he says. “That’s something I want to own.”

But as for The Box party, in addition to “Not Now, I’m Dancing,” it’s also supposed to be called “Bohemian Revolution,” in keeping with the demimonde aesthetic of the short film. The question becomes how to combine the two. Suppnig suggests a themed event, something dress-up, like they do in Vienna—“The old thing brought to the modern”—which Martone has little patience for.

“Meaning what?” Martone asks sharply. “People should dress a certain way? Find a seventeenth-century-inspired gown? They won’t do it.”

Suppnig looks a bit crestfallen. “Just a hat?”

“They won’t do it that week,” Martone says firmly. No costumes. The guests will be too busy with the shows.

After the meeting breaks up, Martone gets a text from Jacobs telling him to come to the window. We look across the street. “Oh, look, there he is!” Martone says. I can see a lean figure in silhouette waving to us. Martone’s eyes are alive. He opens the window, leans out. Then the silhouette is gone.

Soon Jacobs is back in Paris, and Martone invites me over to the duplex they’ve rented in Chelsea while doing the build-out on a $10.4 million West Village townhouse. That night, Martone’s going to Berlin for a few days to meet with BMW—he wants to get his girls modeling for them—and also with a Chandelier client, Melissa Plastic Dreams shoes.

The space itself is huge and manly—they rented it from professional hockey player Scott Gomez, and other than a Terry Richardson photo of Batman and Robin making out, propped on a console, it doesn’t say much about the current occupants. They do love this photo. For Halloween, Martone went as Batman and Jacobs as Robin.

When I arrive, Martone takes me upstairs, where he’s decanting Fresh toiletries into little airport-friendly containers. Vuitton luggage is strewn everywhere. Martone shows me a novel he’s reading, Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, a heady tale of a Paris serial killer searching for the perfect scent. Then we go back downstairs so Martone can eat some sushi he’d bought at Whole Foods. Their housekeeper, Reisa, comments that the couple never eats at home, and, in fact, their huge Sub-Zero fridge is neatly crammed with protein drinks, Diet Coke, VitaminWater, bowls of blueberries and raspberries, and cold cuts.

On the coffee table, stacked with their art books, is the scrapbook from their first-anniversary party, which they had last March at Martone’s old friend and boss Christina Bicalho’s home in São Paulo. “Lorenzo and Marc,” says the front, with appliqués of two cute cartoon bears.

Martone calls Jacobs “Babybear,” and Jacobs calls him “Papabear.” “I’m bigger,” Martone explains. However, he does think that Jacobs “could gain a little weight.”

What does Jacobs like about him? “Strength, I think. I’m not wishy-washy. Like, a menu, for example. Should I have this or that? I look and know what I want.” Is Jacobs decisive? “No!” he exclaims. “He thinks a lot about things before decisions are taken.”

What’s their biggest difference? “Communication. If we have a fight, I go to the guest room and I will probably only see him in two days. And he’s someone who needs to solve everything now.”

One thing they bicker about is Jacobs’s habit of wearing skirts (which, by the way, are all from Comme des Garçons, and he owns about a dozen of them). “I think it was funny in the beginning and cute, but it’s not my taste,” Martone says. Would he ever wear one? “No. Never.” Because real men wear pants? “We had that discussion,” he says of him and Jacobs. “He told me, ‘You are such a forward guy, so open-minded.’ He said, ‘How in the world you’re in the mentality that “Oh, skirts are for girls and not for me?” That’s the old way of thinking.’ I just thought [the skirts were] a little gimmicky. Then he came at me with so many culture references. Between the Japanese culture, kilts … I went to Burma a couple of years ago and the men wear the long, sarong-y, whatever it’s called.”

In addition to the smoking and the skirts, the biggest issue in their relationship is Jacobs’s intense focus on his work. They got in a fight after Jacobs ignored him backstage at one of his shows. (Guest-bedroom time!) Now they try to pay more attention to each other. “That’s become sort of a priority,” Martone says, “like, ‘Oh, you want this relationship to work, with our crazy schedules?,’ so sometimes it’s like, you know, we have options for going to dinner with groups and we say, ‘No, let’s go the two of us, because we need this time for us.’ The mornings are fun. He wakes me with little kisses.”

“I get bored so quickly,” says Martone, who’s lived in São Paulo, Madrid, Paris, and now New York. “I always felt like, ‘Oh, I already know everyone.’ ”

Does Jacobs still not drink? “Socially sometimes, very little. He went through some trouble in the past, as you know, and fixed it.” He reminds me he’s never known Jacobs to be messy. “I’m attracted to people that are happy, optimistic, chatty. I’m not attracted to darkness and weirdo behaviors and wacky personalities. That’s not who I am.”

And speaking of who he’s not, yes, he said they would have a prenup before they would legally be married.

On the day Jacobs is to return from Paris, where he was decorated with the Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres, Martone invites me over for the welcome-home party. He goes into perfect, if somewhat nervous, hostess mode, assembling a salad of greens, chicken, dill, blueberries, and pine nuts tossed in Borsari salt, black pepper, and a lemon-soy tahini, plus a tray of endive with tsatsiki. He warms up mini-quiches and sets out cheeses and arranges it all on a table along with a French news story he’s printed out about Jacobs’s having won the medal.

Some friends come over: Gossip Girl’s Amanda Setton; boyfriends Brian Wolk and Claude Morais (who design the Ruffian clothes line); artist couple John Currin and Rachel Feinstein and their 8-month-old daughter, Flora. Martone cracks open some Champagne and turns on the stereo (Ladyhawke). I ask Feinstein about how Jacobs has changed. “Marc’s happy,” she says, simply. “When I met him, everything was great except his love for himself and his love for someone else. He didn’t seem happy in his own skin. He had to find his own confidence first.”

As Martone gives regular updates from his BlackBerry about Jacobs—he just landed at JFK! He’s stuck in traffic! He’s in Manhattan!—everyone’s on the floor drinking Champagne, eating, playing with Flora. Then we hear a key in the door. It’s Marc! He comes in, wearing a fitted white shirt, tartan kilt, and combat boots, followed by a man carrying his Vuitton luggage. He kisses everyone. Chatter and excitement fill the room. In a moment, he’s flashing his medal. At the ceremony, “I said I wish my father and my grandfather were here to see this,” Jacobs says. His father died when he was 7. “My family’s never really mattered that much to me.”

Martone pours Jacobs a drink and frets that the quiches have been in the oven too long. “Honey, did you burn the roast?” Jacobs jokes. Finally, the family Currin leaves and, after a smoke with one of the Ruffians on the terrace, Jacobs settles on the big man-couch.

How they met, Jacobs’s take:

“I was going to the gym a few months before I met him and had cut my hair.” I’d gone through this very radical transformation from 21 percent body fat, not being in a gym for fifteen years, and eating nothing but McDonald’s and KFC to, like, being the total health-food nut that woke up with wheatgrass and ginger shots, no white flour, no butter, no dairy, no caffeine, no sugar,” he says. Why so extreme? “I had health problems, I had colitis— ulcerative colitis. I still have it.”

He’d just broken up with Jason Preston at the time. “So Lorenzo keeps inviting me to breakfast, lunch, and dinners, and I kept refusing. Not refusing—that sounds wrong—but I kept saying, ‘I don’t eat breakfast, I eat raw eggs and wheatgrass.’ And he’d say, ‘What about lunch?’ and I’d say, ‘I can’t really eat in a restaurant, because I only eat organic food.’ ” We all laugh. “I always had these excuses. And then my [business] partner Robert [Duffy] said, ‘Marc, you complain that you don’t meet the right person, but when somebody wants to go out with you, you make it impossible to get in.’ ”

Why was he really saying no to Martone? “I don’t know,” Jacobs says. He starts to get squirmy and uncomfortable. “Well, actually, I do, probably, on a psychological level, but I’m not going to get into that.” Finally, his trainer, Easy, whom he used to fly to Paris, told him, “ ‘Are you crazy? That guy’s good-looking, so why don’t you go out with him? You’ve been with such a bunch of—’ ” Jacobs stops short. “Unbeknownst to me, Lorenzo was moving to New York the next day, but I said to him, ‘Would you have dinner with me?’ And he said, ‘But only if you’re not going to cancel. I’ve invited you to my birthday, I’ve asked you out, and you always come up with some excuse, and I’m moving to New York tomorrow, so if you’re going to screw me over on a Friday night, I don’t want to go.’ ”

So Martone and Jacobs went to dinner—to Kai, a Japanese restaurant. What was he thinking about Martone? “I thought it was great, I thought he was hot and sexy and charming, fun.” But the question in his mind was: “Why would someone like him want to be with me?”

After a moment of silence, I ask him, why do you think? “I still don’t know the answer to that,” he says.

So what did he see in Martone? “Well, I just saw someone who was, like, really wonderful and fun and interested in so many things. Lorenzo has this amazing curiosity and he has this really beautiful and genuine, authentic love of people. Almost like a child. Over the years, again for a lot of different reasons, I became … I don’t know if jaded is the right word, but I don’t really like being in social situations. But then when I met Lorenzo and I got to enjoy things that I used to enjoy through the eyes and the enthusiasm of someone else … ” He pauses. “This is getting, like, heavy.”

Martone finally breaks in. “Um, you just wanted a quote or something, right, you said?” he asks me.

Is Martone really so centered and calm? I ask Jacobs. “Centered and calm? He’s a control freak! We threw a birthday party for him and he was like, ‘Okay, everybody has to eat now because we have to be at the next place in one hour.’ He was sooo micromanaging everything.” Martone laughs along with us. “And he’s also, culturally, there’s a certain machismo that Lorenzo has and a certain ego about what it is to be a man and to take care of things and do things and have order in things, and I’m not like that.”

Weirdly, at this point, the final theme song from The Devil Wears Prada—when Anne Hathaway throws her hated cell phone into the fountain—comes on the stereo.

Two days later, Martone and I meet at Industria Superstudio for lunch before he heads off to the Grammys to promote his girls. He’s overseeing the shooting of a look book for Chandelier client Rafael Cennamo, a young, Venezuelan couture designer. Everything is beautiful, controlled, perfect—the models, Cennamo’s racks and racks of glittery, opulent, neo-eighties dresses, the table full of fiercely spiked and platformed Louboutins and YSLs—even the people working on the shoot. Martone glides here and there, commenting on his favorite gowns, positioning Cennamo in just the right light.

Earlier, I’d asked Martone if he’d been attracted to the old, less physically self-actualized Jacobs, and he was honest about his preference for the prettier current version. “It’s not someone I’d be sexually attracted to. It’s quirky, like, fun to watch, but I wouldn’t go, like, ‘Oh, God.’ ” What if Jacobs stopped taking quite as good care of himself as he does now? “I would put pressure for him to lose weight,” says Martone, laughing. But then he becomes more serious. “You’re attracted to someone or something initially for a reason, usually more superficial, external. And then you start loving things and people for internal reasons more, less tangible than beauty. So I guess I’d kind of put up with something if it happened, like, if the beauty factor goes down.”

Which sounds, as much as anything, like commitment, especially from someone who’s traveled the world to get right where he is right now. “With more maturity,” he says, philosophically, “You learn there’s no next. It’s really about building where you are. Also, New York kind of feels like the top of the world, in a way. It’s all downhill after here.”