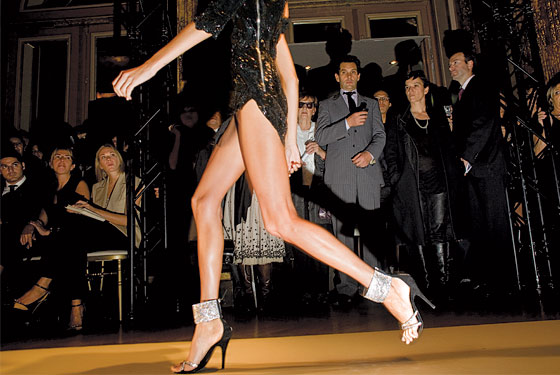

There’s a famous expression about what happens to fashion when the financial markets get grim: If the economy’s down, hemlines follow. There’s the Lipstick Index, too, the none-too-scientific maxim that during tough times, consumers are more likely to splurge on the little things. No Chanel dress or bag or shoes? How about a creamy $27 tube of Vamp instead? As this article goes to press, the Dow is hovering somewhere in the 9,000 range—a low it achieved right after the European collections—which meant that an average morning at the shows was this: Read about the Dow dropping 700 points in your morning Herald Tribune, then traipse off to watch Dolce & Gabbana walk gilt, brocade, and some very elaborate silk pajamas down a runway. Flip back through that paper—foreclosures, war—and then look back up, at Louis Vuitton, at a four-figure pair of shoes covered in a pop-tastic, happy-days mix of ribbons and beads. Then comes the news, just a few weeks later, that the guy who made those bedazzled clompers—Marc Jacobs—has canceled his holiday party because of the “financial climate.”

How does one digest, appreciate, wear fashion and not feel like Marie Antoinette (or at least Sarah “$150,000” Palin) choking on a mound of Chantilly while, outside, Paris burns?

Fashion has survived worse—wars, depressions, terrorist attacks—without ever packing up its mink tails and calling it a night. At no point have people stopped wanting new things to wear and to smell, to smear on their faces or strap on their feet. As Jeffrey Kalinsky (owner of Jeffrey New York) says, “There’s still going to be bar mitzvahs.”

But right now, it doesn’t feel comfortable to spend a lot of money on clothes, or even to celebrate the idea of spending a lot of money on clothes. This business, so much about taste, has to sort out how to be tasteful.

Fashion’s had a good long run in the past several years, with new labels, new looks, and a rapidly growing fan base. There are television shows and blogs and endless fanzines bringing it to the populace, writing tirelessly about designers and editors. Once aspirational, even remote luxury brands—and their designers—are now household names, and all this attention means that it’s not uncommon for an ordinary pair of jeans to cost $200. To keep it entertaining, the shows—which at their core are really high-end trade shows—seem to resort more and more to theatrics. Alexander McQueen took his bow last month in a full-body bunny suit, Karl Lagerfeld’s sets at Chanel have grown to circuslike proportions, and of course there was Sacha Baron Cohen’s Brüno running around with a tampon in his mouth (see page 44). But there were also those grim headlines and, more recently, the retail sales for October, a key pre-holiday selling period: Neiman Marcus off by 27.6 percent, Saks down 16.6 percent. The unease is palpable.

“This moment,” says Kalinsky, “forces you to return to who you are and what you believe in.”

Which is … what?

It’s unlikely that we’ll move from our moment of fashion fanaticism to Maoist work smocks and sensible shoes, at least if history is any guide. Weirdly enough, the first instinct of designers and retailers has been the opposite. Haute fashion is going extremely haute, earning its paycheck, so to speak, but also pulling back from the last decade’s populism. In the next year or so, fashion may close ranks, getting smaller and even more luxe, as its customers become fewer and farther (Russia, China, Dubai) between.

Similar scenarios have played out before. “Often, in times of economic decline, fashion becomes more romantic, more escapist,” says Andrew Bolton, curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute. “If you look at the thirties, fashion was at one of its most romantic stages, with Vionnet and Schiaparelli and so on.” Seventies New York, too, with its jersey draping courtesy of Halston, Giorgio Sant’Angelo, and Stephen Burrows, followed the same format.

Fashion was a treat then, an indulgence. Something to take your mind off the dire state of things. (The minimalism that followed the 1987 stock market crash was, according to this theory, an anomaly. But it also came at the end of the Reagan era’s spangly dresses and giant hair. All that simple Calvin Klein and Jil Sander—and Prada’s black nylon backpack as the luxury bag—was palate cleansing.)

Now a combination of the aforementioned hype and what you might call the Project Runway factor has resulted in an extremely sophisticated fashion customer. Savvy Über-consumers who know their brands can get an approximation of them at a high-design-low-price equation at places like H&M and Topshop, so why should they open their wallets?

The pressure’s on major designers to make their case. “People are going to buy less, but they’re going to be much more aware,” says Julie Gilhart, the fashion director of Barneys. She’s been writing spring orders with particular care. “Customers are going to want what they buy to be really, really good. ‘More for less’ shouldn’t be the mantra; it should be ‘less, but that less should definitely be more.’ ” More unique, more fantastic, more, more, more. High fashion right now shouldn’t compete with the Gap—it needs to offer something extremely beautiful and well made. “It just forces you to be more focused,” says designer Thakoon Panichgul, whose $1,200 dresses have popped up on the industry’s new icon, Michelle Obama (who, it should be pointed out, worked a high-low mix on the campaign trail—J.Crew for appearances, Narciso Rodriguez for Election Night).

“It’s about concentrating on special efforts to make pieces with really big impact,” Panichgul continues. He did brisk business this fall with a minidress wrapped in bondage straps, a dress that announces itself as high fashion in no uncertain terms and that will flatter the few rather than the many. “I have to design in a dream,” Panichgul adds. “Reality is too depressing.”

A lot of retailers don’t want to talk about it. Those who do acknowledge switching strategies and making smaller, more-focused buys—still luxurious, but carefully so. “We bought a lot less,” says Kalinsky, “Enough less that I can sleep at night. I was being much more conservative, much more selective.”

Some designers have added lower-priced pieces to their collections. At Lanvin, there are now dresses with all that famous draping, but in jersey rather than silk, and signature trench coats, in Acne denim rather than faille.

The prevailing enthusiasm among retailers, though, is about the expensive pieces. Just a few of them, maybe, but in the current fashion-logic way, that’s what make sense.

“We have just been chariots of fire and bought only what we really love,” says Beth Buccini, co-owner of the Soho boutique Kirna Zabête. “We’re focusing on fashion with a capital F and leaving the basics to someone else.” Kirna Zabête bought loads of Lanvin (“The shoes are like candy,” Buccini says. “I felt like Kirsten Dunst in Marie Antoinette”) and added Balmain (“It’s the most expensive,” she says, “but it’s so the mood right now”). She’s guessing that her customers will still be happy to shell out big bucks for distressed Balmain jeans because “they look like nothing else out there.”

Fashion’s bubble doesn’t exist in a world of logic or rationale. It trades, rather, on fantasy about yourself and about a more attractive, more glamorous version of the world. For the moment, that bubble might be shrinking. But will it pop for good? Never.