When Circuit City closed its doors at the south side of Union Square in February, it seemed to signify something ominous about the declining health of the city itself. Yes, the company was undergoing a national liquidation, but as customers picked over the last remaining Guitar Heroes in the 46,000-square-foot store, it was easy to look out over Union Square Park and imagine all the economic activity in the neighborhood slowing down to a recessionary new normal.

And in fact, the year has turned out to be a brutal one for street-level commerce throughout New York. Storefront vacancies have hit 10 percent in sections of Fifth Avenue, Times Square, and Soho. Major chains have gone bankrupt—including Virgin Megastore, which neighbored Circuit City at One Union Square South and sold its last CD on June 14. So it came as a surprise to many observers that by August, the Related Companies, which owns One Union Square South, had announced that a 24-hour Best Buy would open in November in the Circuit City location, to be followed by a Nordstrom Rack next spring in part of the space where Virgin used to be.

The terms of both deals have not been made public, but area brokers estimate the Nordstrom deal at a healthy $4.2 million a year. “Nordstrom had been looking to move into Manhattan for five years,” says Faith Hope Consolo, head of retail leasing and sales at Prudential Douglas Elliman. “They had looked everywhere.” When the Union Square location opened up, they acted quickly. “The demographics, the foot traffic, the transportation, it’s just a great location for us,” says Pete Nordstrom, the company’s president of merchandising. “Compared to literally any location we have, there’s nothing like it.”

If one of the tests of a robust ecosystem is its ability to adapt to hostile conditions, the reshuffling of Related’s largest commercial tenants suggests something counterintuitive: Union Square has never been healthier. Rachel Meltzer, a research affiliate at NYU’s Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy, has been studying retail in Union Square since 2000, and has watched the neighborhood outpace the rest of Manhattan in attracting and keeping business. Foot traffic in Union Square has risen 59 percent over the past five years. Retail rents tripled between 2005 and 2006, from $100 to $300 a square foot, and have stayed firm since. (Some locations now command as high as $400—midtown and Soho prices.) Vacancy rates are hovering at a tight 3.4 percent. “I don’t think it’s considered a transportation corridor anymore so much as a destination,” says Meltzer.

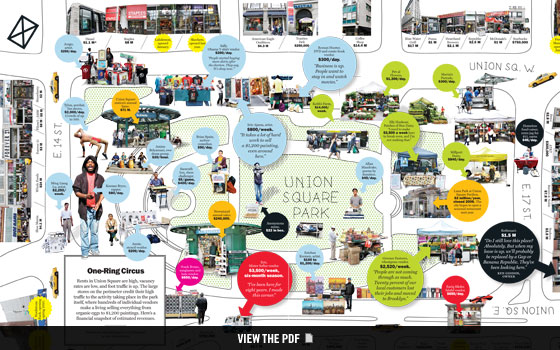

How much street-level commerce takes place in the Square? According to a private market report by Dun & Bradstreet completed in 2008, the 51 retailers and restaurants facing Union Square Park generated a cumulative $202 million in annual revenue last year. The neighborhood’s major player is Whole Foods, which brought in an estimated $24 million in sales and is one of the chain’s most profitable locations nationwide. But unlike other retail centers in New York, Union Square is not dominated by one mega-anchor (like, say, Macy’s at Herald Square). Whole Foods is counterbalanced by a 60,000-square-foot Barnes & Noble (which took in $7.5 million last year), as well as two multiplex cinemas just off the park that together accommodate roughly 1 million annual customers in twenty screens.

Neither are Union Square retailers focused on a specific customer (like the wealthy buyer on Madison, or the tourist at the South Street Seaport). Instead, luxury brands like Diesel and high-end restaurants like Blue Water Grill share the square with downmarket discounters like Filene’s Basement and fast-food joints like McDonald’s. This is likely due to the square’s unique location: It sits above eight subway lines, and rather than being the center of one neighborhood, it borders five. Of the 90,000 residents who live nearby, half of those households earn more than $90,000—but they share the park with over 60,000 roaming students from the nearby colleges, and countless more who make a pit stop while commuting home.

What’s most unusual about the Union Square micro-economy is how much activity takes place within the park itself. This, of course, has much to do with the fact that Union Square actually is a square, and so has a higher proportion of public space than either Herald or Times Square. When the Greenmarket is open four days a week, it serves as another anchor tenant, occupying roughly a third of the park and paying the city $99,171 in annual usage fees. Farmers rent space for a daily fee of $76 per stall length. While the Greenmarket managers will not comment on farmer revenue, reporting suggests they clear $12 million annually. For a month starting after Thanksgiving, the Greenmarket is joined by the Holiday Market, which installs itself at the south end of the park and pays the city $934,637 for the privilege. It pulls in about $2.5 million for its 100 vendors.

Then there is the crowded, informal market of individual entrepreneurs trying to make a buck. On a given day, the park can be surrounded by eight hot-dog stands, two falafel vendors, and five fruit sellers, each of which can gross up to $60,000 a year. On the south side, a few dozen people (some with permits, some without) sell plastic bracelets, baseball hats, tube socks, and other merchandise on folding tables, and about 90 artists who perform and display their work.

In the view of the park’s purists, all this activity is a horrible jumble, making it more outdoor mall than place of passive recreation. Parks commissioner Adrian Benepe would rather limit the sprawl of artists, who operate under First Amendment rights and require no permits. “This is probably not what the Founding Fathers had in mind,” he says. “It turns the park into a flea market. All the space is taken up by selling.” The Union Square Partnership has itself come under criticism for the intense amount of programming it promotes, as well as its intention to hand the renovated pavilion on the park’s north side to a private vendor this spring. “It is a ridiculous plan to further privatize the park,” says Geoffrey Croft, the founder of NYC Park Advocates. Assemblyman Richard Gottfried has also complained about the increasing privatization: “We should not have to sell off pieces of our parks to pay for them.”

But Union Square Park’s ability to accommodate informal, small-scale commerce is what drives much of the store traffic along its perimeter. “Retailers continue to flock here because there are so many eyeballs and feet on the street,” says Kenneth Salzman, a commercial-real-estate broker and longtime neighborhood resident. The most obvious example of this symbiotic relationship is the success of the Greenmarket, which arrived in 1976. “The Greenmarket was the catalyst for the neighborhood’s revival,” says Jennifer Falk, head of the Partnership, which was formed soon after and has been integral to the park’s reconstruction. Over the years, the market helped create a secondary industry in upscale restaurants—beginning with Danny Meyer’s Union Square Café—which in turn drew more people to the square, especially in the evenings. Jenny Schuetz, a professor of real estate at USC who did her postdoctoral work at NYU, says the Greenmarket acts as a destination that attracts people who are likely to make a day of it, shopping for shoes or clothes, having coffee or lunch, maybe going to the movies beforehand. “Once you have the stalls set up for this type of open-air shopping,” says Schuetz, “people are more likely to see the little businesses on the periphery as extensions of a larger market.”

The large chains recognize this. Whole Foods has gone out of its way to cultivate a relationship with the market, often buying leftover produce and featuring seasonal items from the farmers in its prepared-food areas. Along with Barnes & Noble, they allow non-shoppers access to their second-floor cafés, and their facilities serve as de facto public restrooms. “People love to come in and use the bathrooms; we’re famous for them,” says Sam Fishman, Whole Foods’ general manager. “Our feeling is ‘Come in, look around, occupy yourself looking at great-looking food. Maybe you’ll buy a coffee on the way out.’ ”

In a sense, Union Square acts less like an Olmstedian escape from urban life and more like a New England town green—a public gathering place to hawk and purchase wares. And some urban planners suggest that the park could handle even more commerce. Fred Kent, who, as founder of Project for Public Spaces, was responsible for the revamping of Bryant Park, has proposed creating an official artists’ market as a corollary to the farmers’ and crafts markets and suggests reestablishing the park’s northern boundary right up to the Barnes & Noble, doing away with 17th Street. “That way, instead of having 300 people just walking by, you could make the north side of the park a more desirable destination,” he says. “The more elements you have there, the better.” Kent is an urban designer; he’s most interested in making public spaces feel active and alive. But on this subject he sounds very much like Pete Nordstrom. “The best thing about Union Square,” Kent says, “is its uncontrolled chaos.”

Map by Jason Lee. Map photographs by Hannah Whitaker/New York Magazine; Kevin Gray.