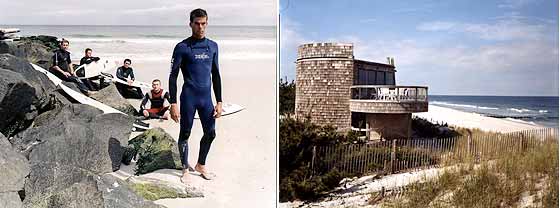

The first storm of summer is rolling toward the Jersey Shore, and for Randy Townsend that means one thing: Surf. A lean 26-year-old with spiky hair and freckles, Townsend cuts expertly through the waves as a half-dozen guys in wetsuits bob in the foam. His nickname is Randazzle, and he’s a star in this righteous place: Long Beach Island.

LBI, as it’s called in Jersey, is a sandbar running along eighteen miles of the shore, dotted with about a dozen towns. It’s a mile wide at its broadest, two or three blocks at its narrowest. The summer community is different from the crowd in the Hamptons: a pleasing mash-up of Wall Streeters, crusty fishermen, and surf rats who consider the waves at LBI the best on the East Coast. The town of Barnegat Light, on the northern tip, has a landmark red-and-white lighthouse and salty docks; Loveladies has megamansions with built-in helicopter landing pads. (Odd municipal names are legion: Loveladies adjoins Harvey Cedars, a little way up from Ship Bottom.) Beach Haven is full of kids, from skimboarding shaggy-haired dudes to heartbreak Britney teens at the pizza shop. “The island is the most laid-back and open-arms place around,” says Townsend, a lifelong resident and pro surfer. “Everyone can find a little bit of happiness here.”

As Townsend wades out of the ocean in Harvey Cedars, a muddy bulldozer piles sand in his path, part of the latest measure against the forces of erosion. In October, 16,000 cubic yards of sand were trucked in. Mayor Jonathan Oldham says it took 40 trucks a day for 40 days to haul the stuff. As Dr. Karl Nordstrom of the Institute of Marine & Coastal Sciences at Rutgers University says, “The dunes are hanging on by a thread.”

The Jersey coast has what’s called a “negative sediment budget.” Since no big river like the Mississippi or the Nile deposits sand here, and lots of waves take material away, the beaches tend to shrink. “Without replenishment, the areas most under pressure start to retreat,” says Keith Watson, the project manager from the United States Army Corps of Engineers. The houses here are built on piles driven into the sand. So if the beach goes, “you’ll see homes fall into the water.”

Long Beach Island is especially vulnerable because it averages only six feet above sea level, and it is losing the little protection it has. Rising tides and increased storm activity have translated into a loss of three or four feet of dune, in the hardest-hit areas, every year since the mid-nineties. Places like Long Beach Island are where the impact of global warming will show up first. What happens here is a preview of what could come in the Hamptons, Fire Island, Long Beach, even the Rockaways.

The Corps—effectively the construction arm of the federal government—and New Jersey’s Department of Environmental Protection have a plan to save the island. Ships called hopper dredges will vacuum up 11 million cubic yards of soupy wet sand. Once each ship is full, it will move in, hook up to a big pump, and funnel sand onto the beach like some mad Dr. Seuss machine. Bulldozers will then spread and grade the new sand. The beach will be broadened, and the dunes will be built up by two feet. Congress and the state have jointly approved $71 million for the project, starting with nearly $8 million this year and slightly more for 2007. At that rate, reconstruction will take five to eight years. When the beaches shrink again, the Feds will beef them up once more (assuming the funds keep coming). If they don’t, it’s hard to generalize what will happen, but some dunes will likely vanish in five years. After that, the waves will crash directly onto foundations and windows, and they won’t last long either.

Spending of this year’s funds must begin by September 30. It hasn’t started yet, largely because the surfers and the homeowners, usually at odds, have joined to fight the project. Their complaints differ, but both groups would rather see the island wash away than give in. “We’re fighting two monsters,” says oceanfront homeowner Joe Barrett, “Godzilla from the sea, and King Kong from Trenton.”

Surfer Chris Manthey has two words to describe the Feds’ project: “prefab McBeaches.” The Corps, he says, is applying a brute-force solution that’s ill-suited to areas that are treasured by swimmers and surfers. Though Long Beach Island is not as famous as, say, the north shore of Hawaii, it holds a rich place in America’s surf culture. Ron Jon Surf Shop, a national chain, got its start here in 1959 when a local began selling boards from the back of his van. A giant Ron Jon store greets arrivals coming over the bridge from the mainland. LBI has more than twenty distinct beach breaks: Experts prefer Harvey Cedars, the floaters go to Ship Bottom and Surf City.

Right now, the waves roll in from deep water and break on shallow underwater sandbars. Because the breaks are far from the beach, surfers have space to catch the wave and ride. But, the surfers say, when the beach is extended seaward, the gradual slope of the seafloor will be replaced by a steep drop-off. Waves traveling across the ocean will hit this cliff, jack up, and then crash down flat onto the new beach. You can’t surf them, and one lifeguard at a post-replenishment beach reports a rise in neck and spinal injuries and shoulder dislocations. “Their project is all about protecting the buildings,” says John Weber, the East Coast regional manager of the Surfrider Foundation. “They’re treating the ocean like a hazard. But a beach where the recreation is destroyed is not a beach you want to go to.”

Up the shore in the town of Monmouth, the Surfrider Foundation claims that the Corps work affected 30 breaks before the locals started asking questions. “I’ve tried to get the Army Corps to discuss the impact on recreation, the environment, and the economy,” says William Rosenblatt, the former mayor and a trustee of Loch Arbour Village, in Monmouth. He cites “a total loss of surfing” nearby, and he and his fellow trustees have kept their town out of the program.

The surfers also pitched a modified plan to NJDEP, one that calls for less sand to be pumped, but they can’t approach the state’s formidable research. A seven-year feasibility study explored myriad options, including “hardened structures” like seawalls. Given the island’s negative sediment budget, the Corps arrived at one solution: beach fill, and the more the better. “The longevity of the project is based on the quantity of sand,” says Watson. “If we had our druthers, we’d give the island a 500-foot[-deep] beach.”In beach-replenished places like Fire Island and Rehoboth, homeowners have been dismayed to see their expensive new sand drifting back out to sea within months. But scientists say the residents don’t understand beach dynamics. “People say it’s like throwing dollars into the sea,” says Nordstrom, “but actually you’re creating conditions with a healthy economic system. [Replenishment] is the best solution if people don’t want to pack up and leave. It provides the elements that nature can use to reshape that coastal environment.” The sand may wash away in a storm, in other words, but in doing so, it diffuses the sea’s fury. Then the Army pumps it back to stop the next hurricane. (Sometimes, it comes back by natural action.) The dunes are a sacrificial cushion. No plan, however, can make LBI invulnerable. The Corps stresses words like the “reduction” of storm damage, not “elimination” of it. Without the added sand, the Feds say, homes teetering on the edge of the dunes really will come down sooner rather than later. As for concerns over swimming and surfing, Watson says that any changes to the seafloor smooth out pretty quickly. He says the Corps is committed to building a slope that works for surfers, and he claims that LBI’s surf breaks will return within a year. But he gives no guarantees. “If a large or severe storm event comes,” Watson says, “the beach will change in a day.”

Randy Townsend says he’s in favor of some replenishment, but he waxes philosophic about the standoff. “Who are we to try to tame Mother Nature?” he says. “It’s only a matter of time before the ocean washes this island away.” Some extremist surfers—the “abandonists”—are even more hands-off. Let it go, they say, houses be damned.

In order to start pumping sand, the NJDEP and Army Corps need about 800 oceanfront property holders to sign easements. The documents do two things: First, they grant the government the right, in perpetuity, to rebuild the dunes on private land. “This is not a one-shot deal,” says Dave Rosenblatt, administrator of the NJDEP’s Office of Engineering & Construction. “We’re going to have to come back and redo this.”

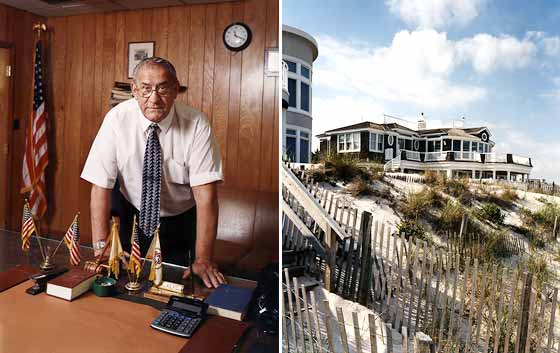

Second, because this is a federal project, it must also fulfill the public interest, which boils down to adding more toilets, parking, and public pathways. While the beaches on the island are all public, the pretense of privacy is alive and well. In the ritzy sections of North Beach and Loveladies, the only beach access is down the sandy driveways of homeowners. They have aggressively staked out their territory, pounding dolphin-shaped NO TRESPASSING signs into their lots. The last thing they want is traipsing tourists and stinky toilets. “They’re talking about Port-O-Lets on the beach. The odors will be unavoidable,” fumes Marc Tesler, a retired venture capitalist from Manhattan who owns an oceanfront house. “It’s one more case of highly placed politicians glomming on to federal money because they can.”

So a subsidiary skirmish is breaking out among the oceanfront owners who have signed their easements, those who haven’t, and the inlanders, most of whom want the dunes rebuilt. But the holdouts have the upper hand. “The erosion makes me nervous,” says William Kunz, who has lived on the ocean in Long Beach Township for 25 years, “but it doesn’t mean I’m going to adjust my principles. I’m not [signing away] my property!”

Kunz is among the 55 owners represented by attorney Kenneth Porro. Not only do they not want the Feds on their land in perpetuity, they don’t want the dunes raised at all. “They bought oceanfront homes for the ocean view, the breeze, the sights,” Porro says, “and to have these walls of sand—these monstrosity walls!—in front of their homes is ridiculous. That’s why they refuse to sign, because it’s not a reasonable plan.”

“I looked up and saw the ocean breaking in the streets,” says Leonard Connors. “It’s like Katrina. If they knew what was coming, they would run.”

Not all the dunes on the island are in bad shape, they argue. Kunz points to his own well-insulated property: For years, he has maintained his dune fence, as has his neighbor, and their only flooding has been from the bay side of the island. It’s not that they’re against replenishment, they say; they just want it kept to areas that really need it. Porro says his opponents are “utilizing scare tactics. They say the dunes are there to protect the property, so if you don’t sign this easement, you’re creating damage to the entire community. So the dunes get good press from people who are not educated. But if you live inland, this dune ain’t doing nothing for you.”

The inlanders, as well as the oceanfront homeowners who have signed on, don’t agree. “People don’t understand that [Katrina] could happen here,” says Wendy Mae Chambers, head of the Harvey Cedars Tax Payers Association, who has been trying to bring the resistance around. “It’s serious. People will die.” As Michael Pasnik, a Somerset attorney who signed an easement for his summer home, says, “This is bigger than just my house. We have to protect the island. The entire economy of the shore could be affected if we don’t.” New Jersey’s second-biggest business sector is tourism, and it brings in $30 billion per year, half of that from the shore counties. “I’d rather have a big, safe beach, even if my view was lessened,” says Nels Kauppila, managing director of JPMorgan in New York, who also signed on.

But with the Feds unwilling to compromise on the terms of the easements, there’s little they can do to change the holdouts’ minds. “No one likes the word perpetuity. It puts the hairs up on people’s necks,” says Mayor Oldham, explaining the resistance. “Some people just don’t trust the government.”

Tacked on the office wall of State Senator Leonard T. Connors Jr., across from the driftwood clock, is a framed black-and-white photo showing a flooded group of houses. It’s a shot of the Great Atlantic Storm, which leveled nearly half the buildings on Long Beach Island and killed several people in March 1962. It haunts the 77-year-old Connors, who was there. “I’ve seen the devastation,” he says in his thick Jersey accent. Connors recalls running supplies up the island’s main road in a boat with an outboard motor. “I looked up and saw the ocean breaking in the streets,” he says. “These people haven’t seen it. It’s like Katrina. If they knew what was coming, they would run.”

Connors, a Republican, is a large man with a large presence on LBI. One resident calls him “our Boss Hog.” In addition to being a state senator, he has been the mayor of Surf City for 40 years. He’s used to getting his way, and he’s frustrated with the oceanfront owners. “These are the same people who took the town to tax court,” he says. “They’re just ballbusters.” And yes, a good number of the holdouts are New Yorkers. “I don’t want to characterize people from New York, but they bring large purses of money, and they’re a little more demanding of services than what has traditionally been acceptable.”

Just as Harvey Cedars trucked in sand in October, Connors began using $500,000 of the borough’s emergency funds to dump sand on Surf City’s beaches this May, making an end run around the easements. He also got an ordinance passed that will bill homeowners directly for future dune repairs. Considering the near-constant erosion and the frequent storms, the bills could easily reach tens of thousands of dollars. (Passing laws like this is easy when weekenders are not around to vote.) “There’s a saying in China: ‘No tickee, no shirtee,’ ” he says. “If you don’t sign up, you don’t get sand.”

Even more controversial plans may be on the horizon. By July 4, the Army Corps and NJDEP will tally the easements and plan the next step. Although they’d been asking all along for 100 percent of the easements in affected areas to be signed, that requirement is no longer so cut-and-dried. Just this month, Governor Jon Corzine stepped in, pledging support for the project. Watson now insists that the replenishment will happen, even if the municipalities need to seize the dunes under eminent domain. Though it would be costly—politically and economically—“we could take that property,” Connors admits. Watson goes him one better: “We are going to build beach fill on this island somewhere this year.” Next: Twenty-Five Perfect Places for Outdoor Eating