One night, we got a call about a severely burned patient in a small town. I was working in Texas. A corpsman and I flew out in an Army helicopter. When we got there, we found a patient with bloody burns on his face and arms and legs. He’d been in a house fire, and 40 percent of his body was covered with third-degree burns. He had black soot all over, and blisters and spots on his arms were charred, almost like they were cooked. It smells like burned meat. He was in a lot of pain, writhing and asking for medication. Once we checked his vitals and found they were okay, we gave him some morphine. He was able to talk, but the main thing he kept saying was, “Take away the pain, Doc.” I had to explain that I couldn’t take the pain away completely, because his blood pressure would drop.

The only thing that was going to save him was getting him to a burn center. There’s a 24-hour window when a patient is stable enough to move. In the first 24 hours, if he’s not given enough IV fluids, he’ll go into shock and could die. After that, deaths are mainly the result of infection, if you don’t get the wounds cleaned quickly enough.

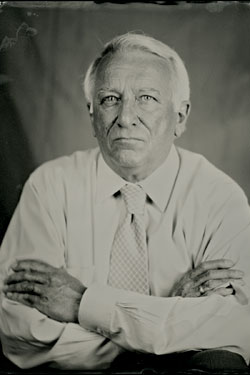

We put him on a stretcher that locks into the floor of the helicopter. We needed to make sure his temperature didn’t drop, because your skin is a major way you maintain body temperature. When it’s destroyed, heat escapes. I felt lonely. This was the first time that the entire burden of making sure this patient survived was resting on me. He was about 39, and I was about 36. He was healthy otherwise, and you tend to put yourself in the patient’s position. I can remember him saying, “Doc, am I gonna live? Can you be sure I’m gonna live?”

When we arrived at the burn center, we reevaluated his vital signs, and that’s when I realized that he had lost the pulses in his arms. The pressure had built up so high under the third-degree burns that it had cut off the blood supply to his hands. A third-degree burn is like leather—it’s not elastic at all. You have to cut the leathery skin so the underlying tissue can swell without pressure building up. That allows blood flow to return.

Next, we debrided him—removing all the dead skin by washing him with a soap solution, using sterile gauze pads. If you leave on the dead burned tissue, it gets infected. He was gritting his teeth and screaming and saying, “Get it over with as soon as you can, Doc.” You divert attention away from the patient as an individual and more to the work. Part of it is an adrenaline rush—that intense feeling that you’ve got to get the job done.

Some blisters will stay intact. Others leak out. When you rub across those areas, you remove the loose skin, break the blisters, and gather that dead skin. This was all done on a stainless-steel table that has a drainage system in it. You’re washing the patient with a hose, and large amounts of dead skin were coming off—in areas like his arm, the entire skin came off, some in sheets as large as the size of his hand. One thing that hit me was “What lies ahead?” I knew that for him to survive, he would have to have six to seven operations.

Once you finish the debriding, you put on antibiotic cream. He was fairly heavily sedated, but he was asking, “Are you ever going to have to do that again?” I told him yes, that we had to do it, twice a day, either until the wound healed or we had skin grafts. At that point, I felt his chances were better than 50-50. It was sunrise when he was wheeled off to bed, and I crashed. I couldn’t do anything except sleep. Two months later, he’d been through six operations. All his third-degree burns had to have a skin graft. He had such big burns, we had to wait for the donor site to heal, and then go back and do another graft. But by the six-week point, he was a survivor.