Last fall, Sanford I. Weill, the former CEO of Citigroup, sold his penthouse apartment at 15 Central Park West to the 22-year-old daughter of Dmitry Rybolovlev, a Russian fertilizer kingpin, for $88 million—more than twice what Weill had paid for it. The sale was the largest ever for an apartment in New York, far exceeding the $48 million paid in 2011 for a twelfth-floor unit in the Plaza Hotel. It seemed inconceivable the record would soon be broken again.

And then, just a few months later, it was, not by another property on the East Side or West Side, but by the penthouse duplex of One57, a not yet completed tower on West 57th Street, near Carnegie Hall. Speaking to a reporter in May, Gary Barnett, the head of Extell, which is developing the property, confirmed that the duplex was in contract for a price upwards of $90 million. He refused to disclose the name of the buyer, saying only that it was recognizable name with a “nice family.”

Historically, each marquee property in New York has been a brand unto itself. There was 740 Park Avenue, with its Candela-designed limestone façade and its scent of old money. There was the Trump International, on Columbus Circle, a glimmering, garish protuberance reminiscent of a bar of gold. Most recently, there was 15 Central Park West, which was completed in 2008 but looks much older—a conscious decision by the architect Robert A. M. Stern, who hoped to achieve a symmetry with Manhattan’s Gold Coast and the stone borders of the park itself. Hedge-fund titan Daniel Ochs has made a home at 15 CPW, as have Goldman Sachs chief Lloyd Blankfein and at least six senior Goldman employees. The place is chunky, stolid, and elegant in an unsurprising kind of way.

One57 is sharp, vertiginous. Where 15 CPW sought to blend into its surroundings, One57 seems determined to stand out—it looms over the drab commercial buildings and hotels on West 58th not so much like a waterfall, as the French architect Christian de Portzamparc has it, but as a gleaming, tumescent phallus.

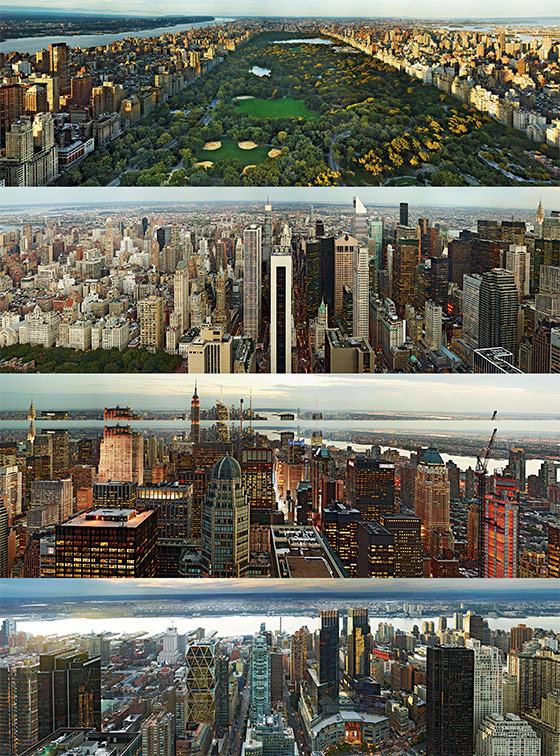

When the building is completed sometime next year, it will stand 1,005 feet tall. That’s taller than the GE Building, taller than the Trump World Tower, and 41 feet shorter than the Chrysler Building. From the penthouse at One57, on the 90th floor, you can see past the verdant rectangle of Central Park, over the knobby sprawl of upper Manhattan, and all the way into Harlem and the Bronx, which recede, on clear summer days, into a fine blue mist. It is the ultimate “fuck you” perk, for the buyer with the ultimate mound of “fuck you” cash—a view that no one else will have, a view designed to reassure a man that he is in fact a lord among serfs, a new king of New York, encased safely in the parapet of his castle.

Because let’s be clear: Although Extell is happy to open the doors of One57 to old Manhattan money—in fact, three residents of 15 CPW are reportedly interested in jumping ship for One57—the building is not really for New Yorkers. It has been built for the fresh-faced global elite and their riptide of foreign money, which swirls every month out of Europe, the Middle East, and Asia and straight into New York City. And foreign buyers don’t want old. They don’t want lived-in. They want new. They want glass. They want steel. Or, as someone involved with the construction of One57 puts it, “Flash matters far more than tradition.”

Extell will sell only 92 residential units in One57 (the first 30 floors will be occupied by a Park Hyatt hotel). This is a very small number. The floor-through units in the top eleven floors start at approximately $50 million; a duplex on the 75th and 76th floor, dubbed “the Winter Garden,” was listed for $115 million. (It went this summer for an undisclosed sum.) These are very big numbers. The contrast has not escaped the marketing team at Extell nor the brokers involved with flogging the units. Pamela Liebman, the president and CEO of the Corcoran Group, which is consulting with Extell on One57, says the tower is the real-estate equivalent of Augusta, the famously exclusive golf club. “You don’t talk about who’s a member,” she says. “You don’t ask who’s a member. But if you can pay the price, you can be a part of the club.”

When 15 CPW first went on the market, the press kept track of every new resident. Extell, by contrast, has repeatedly refused to identify its buyers. Barnett says that his clients want it this way—“I’d love to identify them,” he says. “It’d only help us”—but the protestation comes off as a little disingenuous, and it’s hard not to see the whole cloak-and-dagger thing as just another way to play up interest in the building.

Besides, plenty of information has already trickled out, as it usually does. A Nigerian has purchased a unit in the building, Barnett recently admitted. So have a few Europeans and two Chinese. Lawrence Stroll, the Quebeçois co-director of Michael Kors, bought a unit on the 85th floor for $50 million. His business partner, Silas Chou, who comes from Hong Kong, paid roughly the same amount for his own equivalent unit three floors below. Other buyers include Michael Holtz, a travel-agency magnate, and Richard Kringstein, CEO of the Herman Kay Company.

According to one prominent broker, only a minority of buyers will use the building as a permanent residence. “Everyone else—this is one for their portfolio,” the broker explains. “It’ll be a really great one for a while, I’m sure. These are the kind of billionaires that own in Hong Kong and London and some place in St. Barts. They’re collecting homes as they collect art.”

Catch that? It was subtle. So let us offer our own humble translation: All these aforementioned global elites, who have agreed to fork over near-unfathomable sums of cash for apartments in One57—many of these people are not actually going to live in the building. Sure, they’ll swing by occasionally, long enough to enjoy the view, but for the most part, their apartments will be an investment, a collectible item, a safe-deposit box.

It is not impossible to imagine a day when, gazing up from the sidewalk at West 57th Street, you might find the tallest ghost town in the world, a spire paid for but not actually occupied, unlit but for the flicker of shadow and the zigzag flash of a vacuum across a rosewood floor.

From the ground level, the construction elevator at One57 hugs the flank of the building for twenty floors, nestled comfortably in the grip of the surrounding landscape. Then, like a rocket leaving the launchpad, it jolts into open air, and the rooftops of midtown Manhattan drop precipitously away. The three residential elevators at One57 will travel at roughly twenty miles an hour and scale the entire height of the building in 40 seconds. The construction elevator moves much more slowly than that, and as you climb onboard, the first thing you hear is the screech of the gears overhead.

On a brisk day last month, I ride to the top of One57 with Nicholas Grecco and Ralph Esposito, executives with Lend Lease, a multinational contracting company. In college, Grecco worked in construction for high-rises in midtown, and he saunters confidently to the edge of the elevator, peering outward. Esposito, who has bronze skin and unyielding gold hair, is less sure of himself. He uses his hand to brace himself on the wall, and when a fleet of workers climb onboard, pushing a quiver of metal poles, he clings to the top posts of the pallet. He does not look down. “You tell yourself nothing can happen,” he smiles tightly.

On any given day, there are approximately 400 workers on site at One57. Those workers are all contracted by Lend Lease, of which Esposito is the managing director and president. Grecco is project executive for One57. It is a full-time job, not so different from running a particularly fractious symphony orchestra. There is a lot of talent, a lot of ego, and a lot that can go wrong. Grecco and his team of 44 supervisors and sub-managers work out of a suite of cramped offices on 57th Street; they will not leave until construction is complete. “It’s a real process,” he says.

The elevator stops at the 89th floor—the site of the record-breaking penthouse duplex. “This is what $90 million looks like,” Grecco announces. It does not look like $90 million. Tufts of twisted rebar are sprouting from the floor. The bathtub in the master bathroom is for now only a grubby basin filled with a couple of crumpled cans of Nestea. FUCK FRANK, someone has written on the concrete nearby.

Considering the scale, construction at One57 has moved relatively quickly. In 2005, this stretch of 57th Street comprised a handful of brownstones, a parking garage, and a once-grand hotel, the Park Savoy. Extell bought out the owners of the brownstones and the parking garage, and Barnett told me he was willing to pay a bit north of $10 million for the Park Savoy. The owners asked for $80 million. So Extell simply built around the hotel, which is now wedged into the dank armpit of One57. (I recently suggested to Barnett that the hotel might benefit from its proximity to his skyscraper. He waited a beat and then grinned. “Nope,” he said.)

In 2009, crews broke ground on the foundation of One57. In order to support 1,000-plus vertical feet of glass and metal, the foundation had to be dug two basement levels deep, through heavy, hard rock—a process that took more than a year. By August 2010, Lend Lease began work on the reinforced columns that make up the innards of the building. One57 grew by a couple of floors a week. For about a year and a half, office workers at the 60-floor Carnegie Hall Tower, which sits across 57th Street, watched as their panoramic view of the park slipped incrementally away; by this April, they were staring at the innards of a bustling construction site. “I think all of us knew someone in those buildings that was unhappy at one point in time,” Grecco says. (This is, of course, an abiding cruelty of Manhattan real estate: One day you’re the One57, and the next you’re the Carnegie Hall Tower.)

I follow Grecco into the “grand salon”—the 2,000-square-foot centerpiece of the penthouse duplex. Construction on skyscrapers works in two distinct phases: First the skeleton of the building is erected, and then the skin is stretched over the bones. In this case, the skin is a series of large interlocking glass panels—some 8,400 in all—which are dropped into place with a machine called a “crab.” But those panels currently extend only two-thirds of the way up the building, so at the moment, the penthouse walls are made of orange netting.

Lend Lease expects to have the building fully enclosed by February, at which point work on the interiors can commence in earnest. “That’s not soon enough but very soon,” Grecco says. “The hardship we’re going to endure is working through the winter at 1,000 feet.”

Grecco parts the netting so I can snap a photo with my phone. In the distance, the lawn at Central Park is visible as an emerald sea. Grecco points northwest. “That’s my corner,” he says. Grecco, although only 51, has been involved in some of the best-known luxury properties in town, including the Park Laurel on West 63rd, the Time Warner Center, and 15 Central Park West. All have been clustered near Columbus Circle, a relatively new area of interest for developers—and a sizable distance from the Gold Coast of yore. “The money has moved west,” Grecco says.

Lend Lease works with a range of developers, some of whom are in direct competition with Extell. I ask Grecco if he ever found himself stuck in the middle. He shrugs. “There is definitely a bit of one-upmanship,” he says. Still, he adds, the spotlight is usually only big enough for one building at a time.

The success of One57 thus far is in large part a matter of timing: No other project can match its size or opulence. Earlier this year, Harry Macklowe, the famed New York developer, started work on a new skyscraper at 432 Park Avenue, where the old Drake Hotel once stood. The building will eventually rise to 1,302 feet, 297 feet higher than One57; the penthouse is on the market for $85 million. But 432 Park won’t open until late 2015 at the earliest—right now, it’s not even a stump in the ground.

The New York headquarters of Sotheby’s International Realty sits on East 61st Street, not far from the edge of Central Park. Nikki Field, a senior vice-president, works in an office on the second floor. “High-net-worth individuals have a short tolerance level for depriving themselves,” she tells me on a recent visit. “I think we found out how short it is. I think it was three years”—from the collapse of Lehman Brothers to 2011—“and then they said they had to spend some money.”

Field is blonde, warm, and slight. A former marketing executive, she has spent much of her professional career as a broker of luxury real estate. In 2011, she and several colleagues were invited to a presentation on One57. Barnett himself presided. Although Extell has its own in-house sales team, it is relying on the assistance of well-known brokers like Field who have large Rolodexes full of potential buyers.

Field has been in the business long enough to have collected a fair number of her prospects from prior deals, but she also does her research. Many of her contacts surfaced after having purchased art or collectibles from a Sotheby’s auction. She travels to China four times a year, is learning Mandarin, and carries business cards printed in Chinese characters. She also works frequently with Middle Eastern, Russian, and European clients (French buyers, staring down the barrel of President François Hollande’s impending 75 percent income tax on millionaires, are especially eager to decamp for American shores). The typical potential buyer is young—thirties to early fifties—and “still upwardly mobile,” Field says. “This is not their last $50 million.”

She notes that every buyer of a floor-through unit in One57 is worth more than ten times the standard definition of the American one percenter (assets of at least $7.5 million). It’s a billionaire’s club, as the New York Times has it. But spend enough time around billionaires, as Field does, and you begin to understand that the checklist of suitable properties is actually relatively short. In fact, it’s a seller’s market. In the past, Knightsbridge in London was a perpetual favorite. Increasingly, given the tumult in the European markets, the United States—and New York in particular—is seen as a much more secure investment.

“Asian money gets here because [buyers] feel the security of the U.S. government will provide them a very safe haven for their finances,” Field says. “So, okay. When you get to New York, where do you go? You look around and you can do what some people have done and buy a Trump name or you can look for the newest and best. International buyers,” she continues, raising one finger at a time, “want new. They want view. And they want the right location.” One57 has all three. And it lacks something else: a co-op board. According to the Post, Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim bin Jaber al-Thani, the prime minister of Qatar, was rejected by three co-op boards at high-end Manhattan properties, including the one at 907 Fifth Avenue, which balked at the size of his entourage and the various security risks. Later, the prime minister reportedly entered talks for the $90 million penthouse duplex at One57. (He appears to have finally landed on a single-family townhouse on 71st Street.)

And yet the risk involved in One57 was obvious to anyone in the room during last year’s sales pitch. Barnett had showcased a potentially incredible product whose success was predicated upon a wager completely out of Barnett’s control: that the economy would remain relatively stable in time to complete construction. There was a sense, Field remembers, “of ‘Is this guy going to be able to deliver in 2014?’ ”

Still, Field says the response from her clients was “remarkable.” Citing a confidentiality agreement, she will not disclose names, nor the exact number of units she has sold, but she will give a laundry list of nationalities: Indian, Canadian, Chinese, Taiwanese. And in conversation she seems eager to hint that it was she who brokered the sale of the penthouse.

All of which—the winks and the nods, the purportedly insane demand, the armies of foreign buyers—would be easy to dismiss as extremely good marketing hype if it didn’t appear to actually be true.

Patrick O’Neill, a Hong Kong–based consultant who works with Chinese buyers—and plans to show clients several units at One57 this month—says that the United States, and New York in particular, is “the perfect dim-sum cart for the Chinese investor.” Back in 2009 and 2010, foreign buyers had little interest in preconstruction purchasing. Now, O’Neill says, high-end inventory is down 25 to 30 percent in New York and prices are up 10 to 15 percent. “If you want to look at this level, suddenly One57”—no matter that it is not finished—“becomes of real interest.”

“The way I usually characterize it is this,” says Jonathan Miller, the president of Miller Samuel, a real-estate appraisal firm. “Luxury real estate is the new global currency.”

So, yes, One57 is doing well. Extremely well, thank you very much. According to Barnett, more than 60 percent of the units are sold, and he expects to have the bulk of the remaining apartments unloaded by early next year. Still, let us, for the sake of argument, outline a few doomsday scenarios, for there is precedent. Here’s one: Extell, in pushing the international character of its new building, manages to alienate native New Yorkers and old-money types, who prefer the limestone environs of the Upper West Side and the Upper East Side—who want history, schools, trees.

“Look, these are people who aspire to be New Yorkers,” architectural historian Andrew Alpern says of the future residents of One57. “I’m a native New Yorker. I’m such a New Yorker that when you cut me, black coffee comes out. If it were me, if I had ten, fifteen million dollars, I’d spend it on 15 Central Park West. These international people, they’re a foreign breed to me. I feel comfortable with my own kind. I suspect others do, too.”

Second supposition: The economy tanks. The U.S. economy and the global economy, too. Money dries up. Construction stalls. This actually almost happened early in the history of One57, which was conceived almost ten years ago and got a false start in 2008. Back then, the situation was bad, but not calamitous: The foundation hadn’t been dug. Now it would be a disaster: One57, not yet fully enclosed in its glass skin, would stand open to the elements, its orange plastic netting flapping in the winter breeze.

The obvious analogue here is One Madison Park, a silvery, stark 60-story condo tower on East 22nd Street. Work on One Madison Park commenced in 2006, but a seemingly endless string of financial and legal misadventures—including near bankruptcy—kept the building unfinished for years. Sales at One Madison Park are expected to begin anew this winter, although it seems clear that the place has lost much of its luster. Luxury real-estate is like that: Perceived cultural cachet and momentum are everything.

Keep in mind that until the deals close, in 2013, the buyers at One57 are really only potential buyers—they’ve put down sizable deposits (tens of millions in some cases), but they can still walk away. Adam Leitman Bailey, a veteran real-estate lawyer, says Extell will likely have one year after the promised delivery date to present an apartment to a buyer. After that, the buyer could legally cancel his contract. Alternatively, he might attempt to negotiate a new price for the unit with Extell, which would suddenly find itself in a much less confident position of leverage.

“Remember when all those buyers walked from their contracts post-Lehman?” asks one prominent real-estate analyst. “The minute the cycle turns, they’re gone. This is the most fragile of all markets.” As for the developer, the analyst adds, “he would take the hit and take the deposits and pray people think it was only the cycle that took him down.”

This possibility has not escaped Barnett. Four years ago, he says, he got “hammered.” “Truthfully,” he adds, “I thought that market was going to come down, but not as sharply and deeply as it did. When Lehman crashed, everything fell fast. Luckily it came back quickly.”

I ask him if he worries it can happen again. “I won’t say I worry so much but it’s in the back of my mind that—” He stops himself. “You know: Don’t get caught again,” he says.

On a warm day at the end of last month, I follow Barnett on a tour of One57. He is eager to see the progress on the Park Hyatt hotel, which is scheduled to open at the end of 2013, a few months after the residential units are filled. He walks quickly and purposefully through the back entrance of the building on West 58th Street and down a long tunnel of scaffolding. He is trailed by a young Extell employee named Brian McGrath.

“They’re Sheetrocking today,” McGrath shouts.

“Haven’t they Sheetrocked already?” Barnett asks.

“About 70 percent.”

“Yeah?” Barnett says, raising an eyebrow. He is wearing a sleek black suit, a silk floral tie, and a custom blue construction helmet, which is emblazoned on one side with his name. He steps easily around a pile of cinderblocks and fishes an antique-looking flip phone out of his pocket.

“Gotta call you back,” he says and hangs up.

Barnett was a diamond dealer before he was a developer, and he got his start managing New York property from Belgium, where he was living at the time. He has learned everything he knows, he says, by watching his buildings rise. Barnett often stops by One57 unannounced and pokes through the building, sometimes with a floor plan under one elbow, asking questions. “He’s very hands-on,” says one person who has worked with him. “It’s a plus and a minus.”

We climb into the construction elevator and ride to the 62nd floor. Unlike the penthouse, which is open-air, the shell of the building is affixed here, and the sun bends through the glass and spills across the concrete. “Beautiful,” Barnett says, mostly to himself.

Part of Barnett’s mystique, aside from his intensely guarded sense of privacy—his representatives made him available for interview on the condition that I wouldn’t pry into his personal life—is his ability to secure massive amounts of funding when other developers could not. For One57, he worked with a syndicate of lenders that included Bank of America and Abu Dhabi International Bank. Steve Kenny, of Bank of America Merrill Lynch, says he had never worked with Abu Dhabi International Bank but brought them to the table after multiple presentations from Barnett and a vet from an independent construction contractor. In the end, the syndicate invested $700 million. (The total cost of the building, including land and interest, will be $1.5 billion.) I suggest to Barnett that he must get queasy thinking about all that cash. “No,” he says. “It’s a tough business, but you don’t need to be a genius to be in it and to do well. You have to be more lucky than anything else.”

These days, in fact, Barnett talks frequently about luck. He talks about it mock-sheepishly, with a downturned smile, in the manner of a poker player who does not actually believe he has been lucky—and in fact may not believe in luck at all—but wants you to believe that he believes in luck in order not to look ungrateful or too full of pride.

We ride the elevator back down to the ground floor. Barnett walks headlong into the traffic on 58th Street, shooing aside an oncoming minivan, not stopping for a moment, still talking. He is telling me his new favorite story, one of two prospective buyers he had recently turned away. First, he suggests, consider the case of Nick Candy, the brash young British developer of One Hyde Park, in London, possibly the only property comparable to One57 in terms of asking price. Candy wanted a unit in One57 and the ability to flip it before the contract had closed. Barnett refused him, and Candy “went around and bad-mouthed us,” Barnett says.

“I’m selling my own units,” Barnett tells me. “I believe that prices are going to go up. I don’t want to give my profit away to speculators.”

Instance two: entrepreneur Michael Hirtenstein. A few months ago, Hirtenstein paid a construction worker $200 to cart his iPad to the 47th floor and shoot a video from the unit he was interested in purchasing. When the worker returned, Hirtenstein found he was staring at a much more cluttered view than he’d seen in official Extell brochures. (As Hirtenstein remembers it: “It was extremely misleading. Barnett found out I’d done it, and he was obviously freaked out. Suddenly it’s, ‘Okay, we’re not doing business.’ ”)

Recalling the spat, which was dissected ad nauseam on real-estate blogs, Barnett frowns. “We weren’t so excited about him anyhow,” he says.

At the corner of Fifth Avenue, we are stopped by a short, silver-haired man in a blue Moncler jacket. He is wearing suede slip-ons and no socks and chunky eyeglasses. “Gary,” the man says. “Tommy. Tommy Hilfiger. Good to see you.”

Hilfiger, who owns a $25 million duplex in the Plaza, has long been rumored to be interested in buying at One57. Now he presses Barnett on details. “I’d really like to go up,” he says.

“So? The full floors are going quick.”

“The thing, is my apartment is so special in the Plaza. My wife …” Hilfiger trails off.

“It is beautiful,” Barnett agrees. “But bring her up [in One57] and look at the views.”

Hilfiger mentions that Silas Chou and Lawrence Stroll (who were early investors in Tommy Hilfiger) were “very happy” with their new purchases. “Do you have something left in the eighties?” he asks.

“We do have something left in the eighties. I think 84.”

“You around all week?”

“Yeah, I’m around. Except Yom Kippur. That’s Wednesday.”

Hilfiger nods. “Congratulations on everything,” he says. “You got the world talking.”

Barnett is silent for almost a full block. And then, turning to me, he says, “I promise you, that was not staged.”